Genocidal Empires

German Colonialism in Africa and the Third Reich

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

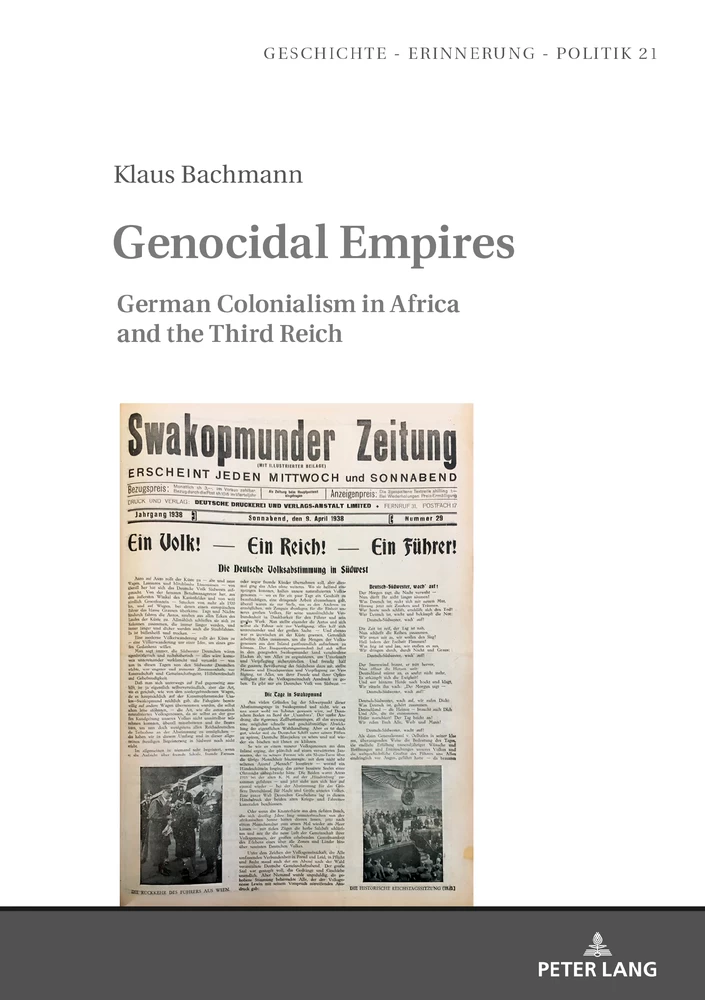

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- On terminology

- Introduction: German South-West Africa 1904–1907 – The exception to German colonial rule

- 1. The genocide that did not take place

- 1.1 The causes of war

- 1.2 The policy shift in 1904

- 2. The genocide that did take place

- 2.1 The war against the Nama

- 2.2 The camps

- 2.3 The deportations

- 2.4 The consequences of Germany’s colonial policy in Namibia

- 3. Germany’s colonial policy in the light of international criminal law

- 3.1 The evolution of the genocide concept in international criminal law

- 3.2 Genocide without genocidal intent?

- 3.3 Was quelling the Herero uprising genocide?

- 3.4 Destroying the Herero and Nama as ethnic groups

- 3.5 The responsibility of superiors and peers

- 4. How ICL sheds new light on other cases of extreme colonial violence in the German empire

- 4.1 Genocide in German East Africa?

- 4.2 The case of the Bushmen

- 5. From Africa to Auschwitz, from Windhuk to the Holocaust?

- 5.1 Institutional continuity between the Kaiserreich’s colonial bureaucracy and the Third Reich

- 5.2 Continuity of informal knowledge

- 5.3 Elite continuity between German South-West Africa and the Third Reich

- 6. From Berlin to Cape Town and Windhoek

- 6.1 The Auslandsorganisation der NSDAP

- 6.2 The failure of the Auslandsorganisation in South-West Africa

- 6.3 Higher stakes: South Africa

- 6.4 Operation Weissdorn

- 7. Patterns of extreme violence in the German colonies and German-occupied Central and Eastern Europe

- 7.1 An early version of Apartheid?

- Conclusion

- Annex

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series Index

German colonialism belongs to the darker parts of the German past. It remains a puzzle until today. It was neither profitable for Germany, nor was it a period of which contemporary or later generations could be proud of. Although pride was predominant in the political speeches of the day, throughout the colonial period between the Berlin Conference and World War I German officers, German bureaucrats and German soldiers looked up to the British as the more experienced, more senior colonizers, from which the Germans could learn how to effectively deal with “the natives”, how to organize colonies, and how to develop them. Before the colonial adventure had started, it was already over. Less than 30 years after the first German emissaries had concluded their first treaties with native chieftains, troops of the Entente overran the German positions in Togo, Kamerun and German South-West Africa, forcing German troops to surrender and taking control of the local administration. Only in German East Africa the German troops did not surrender until the armistice in Compiègne, but even until the end of the war, they never exercised effective control over the whole territory of German East Africa.

During these 30 years, the German administration of the colonies faced a plethora of often violent conflicts, sometimes between the local ethnic groups, sometimes between ethnic groups and the German colonial administration. Three of these conflicts stand out from all the others, not only because of the utmost cruelty by which they were finally settled, but also because of their prominence in historical and political debates in the former colonies and the mainland.

The first one is the war against the Herero, which is today widely regarded as the first genocide of the 20th century, committed by Germany. The second is the war against the Nama, another group that stood up to German rule almost immediately after the Herero uprising. And the third is the Maji Maji rebellion in German East Africa, which was quashed in blood by an army consisting mostly of Askaris, that is African and Arab mercenaries who fought under the command of German officers.

The debate on German colonialism has become overshadowed by two topics that are strongly connected to partisan politics and diplomacy. One such topic is the genocide debate, or the tendency to impose the label of genocide on the Nama and Herero wars and to claim that the Kaiserreich, Germany or “the Germans” committed genocide against the Herero and Nama. In most articles and books whose authors agree with the genocide claim, the main argument in its ← 7 | 8 → support is the high number of casualties attributed to the German war strategy. The second important issue, which overshadows the debate about German colonialism in Africa, is the attempt to link the violence which was applied by the German troops in German South-West Africa to the violence later used by the Third Reich in occupied Central and Eastern Europe. Both strands in the scholarly (and partly also political) debate suffer from two main shortcomings.

Many of the authors eager to attach the genocide label to the events in German South-West Africa either do not reveal which definition of genocide they apply, or they base their assumptions on the mere fact that the German war strategy caused a militarily unnecessary high number of victims and did not spare civilians. These authors often know a lot about Namibian and German history, but are unaware of the legal significance of the genocide concept. Sometimes they mention or quote the “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of Genocide” (further the Genocide Convention), which was signed in 1948, but even when they do, they fail to apply its meaning to the events they describe as genocidal. The few historians and sociologists who invoke the Genocide Convention appropriately usually ignore the jurisprudence that has emerged from the judgments and decisions of those international criminal tribunals, which wield jurisdiction over the crime of genocide. This is the first gap that this book fills in. It uses the most precise and most widely acknowledged concept of genocide – the one created by International Criminal Law – in order to assess whether the events in German South-West Africa after 1904 amounted to genocide or not. As the reader will see, this concept differs a lot not only from the popular connotation the genocide label has been given in the media, but also from the original wording of the Genocide Convention and the literal understanding many authors derive from the Convention. This genocide concept is at the same time much more precise, multi-layered and complex than the notions usually applied by politicians, journalists, historians, and social scientists when they argue that a specific real-world massacre was genocidal.

In principle, this is an ahistorical endeavor. It is ahistorical, because at the time when the Nama and the Herero war took place, there was no concept of genocide, no Genocide Convention and there was no court or tribunal that could have judged perpetrators of genocide. The only notion from International Criminal Law1 (which did not yet exist either) that could be applied was that of a war crime or, in other words, of a violation of the 1867 Convention of the Red Cross ← 8 | 9 → and the 1899 Convention regulating warfare on the land.2 Trying to find out whether the conflicts in a German colony at the beginning of the 20th century were genocidal in the meaning of an international agreement which came into being much later is nothing else than measuring the behaviour of people in the past according to norms and values of today, about which they could not know and of which they could not even fathom that they would ever come into being. It is morally unfair with regard to those to whom such an experiment is applied and it is arrogant from the perspective of the historian, who submits people’s past acts to such an experiment. This said, it does make sense from an academic point of view. Neither the social sciences nor historiography have so far developed a comprehensive definition of genocide that is undisputed and coherent enough to bring clarity into the discussion of whether an act of violence was genocidal or not. Very often authors claim such acts of violence to be genocidal without applying any definition of genocide at all, they do so simply because the violence they encounter in the sources is outrageous, widespread and irrational from their point of view; sometimes they do so just because a massacre caused an immense number of (civilian) casualties.3

Not every attempt to assess past conduct in the light of international law which was developed later is in itself ahistorical. At the time of the Nama, Herero and Maji Maji wars in the German colonies, Germany was bound by international humanitarian law, precisely by the Red Cross Convention and The Convention on the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded on the Field of Battle (one of the so-called Hague Conventions, further abbreviated as Hague II). Both conventions put considerable humanitarian constraints on German commanders ← 9 | 10 → and provided legal protection for belligerents and civilians from arbitrary execution and abuse.

The German Empire had a problematic attitude towards these obligations. The government had signed the Red Cross Convention long before 1904 but Germany only ratified it in 1907. Hague II was signed in 1899, entered into force in 1900 and was thus already binding for Germany in 1904.4 In 1911, Hague II and the Red Cross Convention were also added to the internal regulations, which the government sent to the lower echelons of the army. They became part of the Felddienstordnung, and a short summary about the duties arising for individual soldiers from these international agreements was provided to each individual conscript. The summary even described criminal sanctions for violations of these duties.5

Although these steps were undertaken after the Herero and Nama wars, the content of the Red Cross Convention and of Hague II was well known to German commanders, officers, and to the civilian administrators of the colonies. They often referred to them both implicitely and explicitly in their correspondence, and they knew the differences between belligerents and civilians, between prisoners of war and other prisoners very well.

However, this knowledge was not accompanied by appropriate action. The German government had signed these international obligations, but the attitude of political and legal authorities towards international law as such and the specific consequences arising from international law for Germany in case of war remained strongly ambiguous. Many lawyers argued that relations between states could not be regulated at all, because states were the sources of all law and the relations between them governed by violence alone. In a publication following the 1899 conference, the Great General Staff (Große Generalstab) of the German army downplayed the obligations from Hague II as “mere customs” and claimed they could only be obeyed when the “nature and purpose of the war” ← 10 | 11 → allowed it.6 According to leading criminal lawyers, the state could ultimately cherry-pick from these obligations and obey only those beneficial for its war objectives. Germany went so far in this interpretation of international law that its courts even exonerated foreign prisoners of war from charges of war crimes committed against German soldiers during the time of their armed service. They had only obeyed their superiors’ orders, German courts argued, and neither they nor their superiors could be charged under German criminal law.7 This changed only after World War I, when the Reichsgericht suddenly found that killing vulnerable people in war was only legal if committed within the ramifications of international law. But this happened after the Entente powers had imposed on Germany the duty to judge war criminals in the Versaille Peace Treaty.8 Back in 1904, the German attitudes towards international constraints on warfare were biased in several aspects: Germany did not at all see Hague II as legally binding and it did not see the Herero and Nama as an equal counterpart to be treated in accordance with the international law the German authorities saw as a sample of regulations between states.

Additionally, there also was no international enforcement mechanism at work, which could have coerced German officers into compliance with these conventions, and German soldiers were right when they assumed that they could only be held accountable before German courts, which would hardly convict them.9 ← 11 | 12 → The international obligations which Germany had accepted in both conventions were enforceable only in Germany, and they actually were never enforced with regard to crimes committed in the colonies.

Germany did not live up to the obligations it had endorsed in The Hague, but this does not make these obligations non-existent. When the Herero uprising started, there was humanitarian law in force, which could have been applied in practice and which should have prevented the Schutztruppe and the Navy from committing atrocities. Germany was obliged to implement the conventions it had signed, and because it did not, it violated its international duties. Here a reservation is necessary. On the basis of the same legal documents and similar factual findings, Steffen Eicker has come to a different conclusion according to which Germany neither violated the Red Cross Convention nor the Hague Conventions. He does so because he is mostly interested in establishing whether the German Federal Republic, as a successor of the German Empire, can be held legally responsible for atrocities committed in colonial Namibia. He denies this, based on the (in my opinion correct) assumption according to which the Herero were not a state party to these conventions, and Namibia today is not a legal successor to the Herero community.10

My claim is different. It is not about state responsibility and the law regulating relations between states, but about the criminal responsibility of individuals and their obligations towards other individuals. In other words, I claim that the German soldiers were obliged to uphold the standards of International Humanitarian Law and to treat the Herero and Nama according to the Red Cross Convention (which at that time, although not yet ratified by Germany, was part of customary international law and well known to the German authorities) and to Hague II, which had even been signed and ratified by Germany years before the Herero uprising. I claim that treating the Herero and Nama the way they were treated amounted to a violation of these conventions and was punishable as a war crime. Whether today the Herero, Nama or the government of Namibia can (or should) hold Germany accountable for these war crimes is a different issue which requires different arguments. The same applies to the question whether Germany should pay individual compensations or reparations to the Herero, the ← 12 | 13 → Nama or the state of Namibia today. Due to the lack of jurisdiction of an international court, this seems rather to be a political and diplomatic issue, which is beyond the scope of this book.11

Applying both convention’s concepts to the German war conduct against the Nama, Herero and the Maji-Maji movements does make sense for an historian as well as for a lawyer. It shows much more precisely than the sweeping moral claims, which permeate the debate about German colonialism, which crimes were committed, when and by whom, and it shows which actions of the warring parties were legal under the law of the day, no matter how outrageous and repugnant these actions may be for us today. An interesting side effect of this approach is likely to impact the current debate about apologies, compensation and reparations, which representatives of the Herero and Nama communities in Namibia have been requesting from the German government. Applying such a modern, updated notion of genocide to the events in colonial Namibia helps to answer two different questions: whether these claims are legally justified and which concrete actions actually deserve the genocide label, and which do not.

The second politically motivated tendency which overshadows the scholarly debate about the events in German South-West Africa between 1904 and 1907 is enrooted in post-war Germany’s tendency to deal with its past. It is the claim about a causal link that allegedly connects the extreme violence the German military and the colonial administration applied towards the Nama and Herero to the violence which the Third Reich applied in Central and Eastern Europe after 1939. According to some very far-reaching claims in the literature, the Germans ‘learned’ genocide in German South-West Africa and applied this knowledge later either (as some say) in occupied Central and Eastern Europe or (as others say) during the Holocaust. This is the second focus of this book: It tries to test these claims against the evidence that is currently available, by asking whether the elites of the Third Reich were influenced (and if yes, how) by colonial nostalgists and the colonial lobby of the Weimar Republic, and whether the concepts and methods developed in the German colonies were similar to those applied in occupied Poland and the Soviet Union during the war. One of the cornerstones of this test is the question whether the outbreak of irrational violence is better explained by a functionalist bottom-up or an intentionalist top-down approach. ← 13 | 14 → Some of the violence, which came to the fore in both cases, can be explained by rational choice, that is by the fact that the application of violence benefitted those who applied it in one way or another. But there are also cases where the German military, the German administration and German civilians decided to apply extreme violence to the occupied or colonized either without any visible benefit or at a considerable cost which exceeded any benefit they could expect. The most prominent example, which is well known to the wider public, is the case of the Third Reich’s use of its infrastructure, railways, police force for mass deportations of Jews to the death camps at a time when Germany needed all these capabilities for the war effort. As will be shown later in this book, a similar conduct could be observed in German South-West Africa at the beginning of the century. How can we understand such cases of irrational violence? Are they better explained by racially informed intentionalism or by the interplay of factors which were beyond the control of those who became so violent?

These two big controversies shape the structure of the book. It is divided into two main parts. The first part applies International Criminal Law’s (ICL) genocide concept to the events in German South-West Africa (and to a lesser extent also to German East Africa) at the beginning of the 20th century, using the legal notion of genocide as a point of reference for historical research. This experiment will bring some surprising results: Some events, which so far have been almost undisputedly regarded as genocidal, cease to seem as such, whereas others, which have remained untainted by genocide accusations, will appear in a new light. This first part of the book tells the story of the Herero and Nama uprisings and their aftermath as it appears from the currently available archival records. Within this story, it is analyzed whether (and if yes, to what extent) the conduct of the warring parties violated the international obligations which were applicable at the time. It answers the question whether and how the Germans – but also the Herero and Nama – committed war crimes in the light of the Red Cross Convention and Hague II.

The issue of genocide is more complicated due to the complexity of the concept, but also due to the fact that it is applied retroactively to a context when genocide did not yet even exist semantically. It is therefore dealt with in a special chapter, which demonstrates the development of the genocide concept, the underlying legal logic and the jurisprudence which has emerged in recent decades. This chapter answers the question which of the German actions against the Herero and Nama and against the civilian native population of German South-West Africa can be regarded as genocidal in the light of the modern ICL-informed ← 14 | 15 → notion of genocide. It also shows some of the advantages for historical research of using the legal notion of genocide rather than concepts formulated ad hoc.

The second part examines the hypothesis about a continuity between the colonial policies, practices and experiences of the Kaiserreich and the policies of the Third Reich in Central and Eastern Europe more than three decades later. This part also contains some surprises. In the light of the archival records, it is better to speak of a rupture between the Kaiserreich’s colonial policies and the Third Reich’s occupation conduct than about continuity between the two. The Nazi elite did not only not want to learn from the old Kaiserreich and Weimar elites, they also did not have much to learn from, because personal and institutional continuities, which would have normally existed between two generations, had been cut off by the Nazi movement’s ascent to power. It appears that it was not the Nazi movement that learned something from the German settlers in German South-West Africa, but the white political leadership in first the Cape Colony and later the Union of South Africa which adopted measures of race segregation very similar to those of the German settlers. There was continuity – but much more between German South-West Africa and wider South Africa than between German colonies and the Nazi state. This does not mean that there are no causal links between these two worlds – the world of the Kaiserreich and the Third Reich. First of all – both used genocide as a means to achieve political and social objectives. This is nothing new. Much more surprising is another line of continuity, which has so far been ignored even by the booming literature about race relations and gender issues in German colonialism. When drafting the Nuremberg laws and elaborating the means to sever the ties between Aryans and Jews in the Third Reich, a legal concept was applied that had emerged in the colonies and proved much more efficient and fatal for those who fell victim to it than the old racism in the early years of colonialism, which based the rejection of the racial other on physical appearance. It was the emergence and perfection of a bureaucratic, blood-based and legally enrooted racism which left its victims no escape and empowered the state bureaucracy to exclude (and ultimately kill) groups and individuals randomly and without any need for public justification. This racism was a result of the violence between 1904 and 1907 in German South-West and East Africa, and it led to the radicalization of racial persecution, which characterized the Third Reich. These two aspects form the backbone of this book’s title. Both German empires, the Kaiserreich and the Third Reich, were genocidal and linked together by one fatal concept which made the Holocaust possible. ← 15 | 16 →

1 Further: ICL.

2 The Red Cross Convention and the Hague Conventions, which were already known and applicable during German colonial rule, are attached in Annex 1 to this book, together with the information, when they were signed and ratified by German and when they entered into force. They are further mentioned here under the abbreviations of “The Red Cross Convention”, and “Hague II” and “Hague IV”, according to the information retrieved from the online database of Yale University’s Avalon project: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/19th.asp.

3 As will later be shown in chapter 3, many experts in ICL treat genocide as a specific case of a crime against humanity, which is defined as a “widespread and systematic attack on the civilian population”. From ICL’s perspective, it is therefore possible (and the genocide concept in ICL facilitates that) to distinguish certain genocidal acts within a larger event, which in itself was not genocidal, for example, in a case, where within the framework of a large military campaign, during which war crimes were committed, a small part of the military committed genocide against a specific part (for example an ethnic group) of the population, but did not target other communities in the same way.

4 See: https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/ihl/INTRO/150?OpenDocument; and https://verdragenbank.overheid.nl/en/Verdrag/Details/002338. There is a bit of confusion in these databases, because according to the database of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Reichstag ratified Hague II only in 1910. But already years before that, in 1907, Hague II was made public in the official legal publication of the Kaiserreich, the Reichsgesetzblatt. See: Gerd Hankel: Die Leipziger Prozesse. Deutsche Kriegsverbrechen und ihre strafrechtliche Verfolgung nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Hamburg, (Hamburger Edition) 2003, 165.

5 Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 165–166.

6 Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 153.

7 Hankel, Die Leipziger Prozesse, 154.

Details

- Pages

- 384

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631752784

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631752791

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631752807

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631745175

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13834

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (June)

- Keywords

- Namibia Tansania German Empire International Law Foreign policy National Socialism

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018., 384 pp., 7 tables