Behind Closed Doors

Hidden Histories of Children Committed to Care in the Late Nineteenth Century (1882-1899)

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

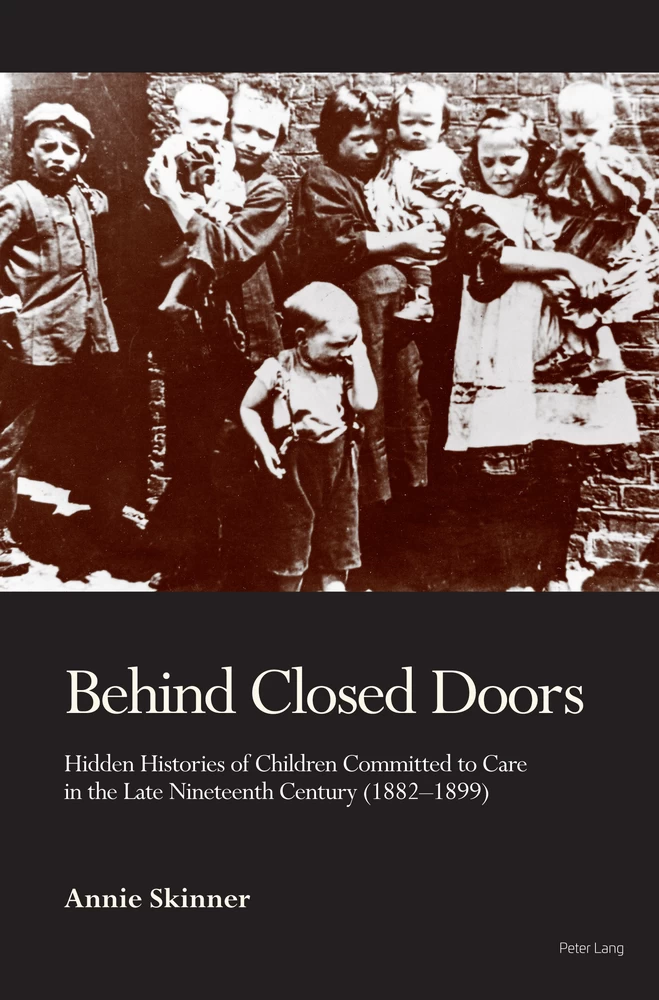

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of photographs

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The evolution of industrial schools and the child rescue movement

- Chapter 2 Legislation, child removal in practice

- Chapter 3 Life in industrial schools

- Chapter 4 Children’s experiences of state removal

- Chapter 5 Parents’ experiences of child removal

- Chapter 6 Those who must be obeyed

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Photographs

Figure 1.Edward Rudolf founder of the WSS

Figure 2.Little girl on admission to the WSS circa 1890

Figure 3.The Mumbles. One of the first WSS industrial schools for girls (1885–1902)

Figure 4.Standon Farm Home. The first WSS industrial school for boys (1885–1947)

Tables

Table 1.Reason for request for care and gender 1882–1899

Table 2.Gender and known ages of children committed to WSS care 1884–1899

Table 3.Analysis of legislation used to commit children to WSS care

Table 4.Family status of committed children 1891 (Gear)

Table 5.Profiles of family backgrounds of children committed to WSS care 1884–1899

Preface

This project emerged out of research into the circumstances that led to children coming into the care of the Waifs and Strays Society at the end of the nineteenth century. In order to understand the reasons behind these admissions I read nearly seven thousand children’s case notes. Unsurprisingly, poverty, illness and death were major contributing factors that led parents to request institutional care for their children. One of my chief concerns has been the process by which decisions were made to admit children to a charitable organization rather than a poor law institution. It soon became clear that the Charity Organisation Society played a role in categorizing children and families as deserving and warranting care; undeserving cases were abandoned to seek assistance from the harsh poor law. As I read these case notes, I was drawn to letters written by children who had been taken into care through the courts. These children had been removed from their families and committed to care until they turned 16.

Intrigued by these hidden stories, I wanted to know more. This led me to engage in further research about child protection in the nineteenth century with the aim of telling the stories from the child’s perspective. Committing a child to care changed the legal status of a child. These children were committed because they had been neglected or abused, but in the process they were criminalized and incarcerated. There were many parties involved in the committal process and the care of committed children. The parameters of child care law were laid down during the nineteenth century, and some aspects of the legislation filtered through into the twentieth century. Fundamental principles of social work were also established during this time, with the Charity Organisation Society playing a lead role. And then attitudes towards parents who were unable to care for their children were shaped within this invidious model of deserving or undeserving.

These children’s letters reveal how the committal process and the attitudes and actions of those involved in it impacted their lives. Their voices ←xiii | xiv→give us first-hand accounts of their removal and institutional experience. The voice of the child is so often missing in historical studies of child care, and the discovery of these letters gives a perfect opportunity to present their voice in what is an under-researched aspect of child care history. Whilst documentary sources used in this book create an understanding of why and how children were removed, the children’s letters tell us what actually happened to them. We hear how they responded to their predicaments and the impact this had. Letters from the children’s parents to the authorities and to their child add to the picture, as they tell us more about the child’s background and their family relationships. In the midst of this we also witness discussions between those involved in committed children’s care.

Reading these children’s stories enable us to understand who was involved in the children’s lives, how the system worked and the impact of contemporary practice on committed children. Insights such as these are of historic value to those working in social or cultural history. They will also be of interest to those whose relatives may have experienced life in these institutions. Most importantly, the children’s stories have been told from their perspective and given a place in history.

Acknowledgements

Firstly, my thanks must go to the Wellcome Trust for awarding me a grant to carry out this research, without this help this book would never have been written. I would like to thank the following for their helpful comments, encouragement and advice on earlier drafts of this book: Harry Hendrick, Una Hopcroft, Patrick (Nigel) Thomas, John Stewart, Steve Taylor and Harriet Waterstone. Particular thanks must go to Sally Bayley who has been of considerable help with her skilled guidance, insight and creativity. Thanks must also go to Oxford Brookes University library staff for their excellent help during lockdown. Throughout this project staff at the Bodleian Library have been most helpful, particularly Isabel McMann and Hannah Chandler. I would also like to thank the Children’s Society for allowing me access to the WSS archives, and their archivists Ian Wakeling, Gabrielle St John-McAlister, Helena Hilton, Julia Feng and Richard Wilson who have been so helpful with their expertise and knowledge about the Waifs and Strays Society. Finally, I would like to thank my husband John Skinner who not only read drafts of this book and offered wise words of advice but also provided some necessary technical advice, moral support and was just there.

Introduction

I don’t know what they took me away for … I didn’t think I had done anything wrong at home and now I have lost every body …1

When she was 10 years old in 1886, Cecily, the author of the letter-extract above, appeared in court and was charged with being in the company of prostitutes. Cecily was committed to care and detained in the care of the Waifs and Strays Society (hereafter WSS), until she was 16 years old under Section 14 of the Industrial Schools Amendment Act 1880. She was sent to live in one of the WSS establishments, Cold Ash Industrial School. There appears no clear reason for her committal other than her association with prostitutes, a fact attributed to her mother’s neglectful care. Nonetheless Cecily was removed from her family, and in the process, her mother lost her parental rights; henceforth, Cecily’s future lay in the hands of the Secretary of State. During the same year Cecily was committed, in England 2,274 boys and 588 girls were committed to industrial schools, the majority under Section 14 of the Industrial Schools Act. Amongst this cohort eighty-one children were committed under the Industrial Schools Amendment Act, because they were found in brothels.2 The number of children committed to care incrementally increased throughout the century.3

Children could be admitted to care on a voluntary basis or taken into care by legal order. Those children taken by law were detained in specific ←1 | 2→accommodation, an industrial school, for the term of their committal. Children were convicted under criminal legislation. Committed children were rescued from abusive, neglected and dangerous environments, and this legal framework provided the basis for future child welfare legislation.4 The legal framework was created in the context of numerous changes in society which included new political, social and cultural dimensions. New debates began to emerge around child welfare legislation underpinned by religion and class structures. Despite the numbers of children that were committed to care under the Industrial Schools Acts in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, we know little about their experiences of growing up in the care of the state.5 Neither do we know much about parents’ experiences when their child was removed, or how the authorities’ practice impacted on the children in their care and their parents, or the interface between state and charitable agencies. This book will turn its attention to society’s shifting attitudes towards the care of children: attitudes that emerged amidst a debate surrounding eugenics and the development of public health policy. Incorporated into these ideologies was a strong emphasis on the importance of motherhood as a critical factor to improve the health and welfare of the next generation.6

Amidst industrial development, increased population, scientific advancement and awareness of social problems, Victorian society saw a growth in the concern for working-class children led by influential well-connected members of the establishment. Overcrowded accommodation, recessions, ←2 | 3→unemployment, poverty and poor standards of living had contributed to the conditions for many working-class families. State help, determined by the deserving and undeserving paradigm, was difficult to obtain outside of the workhouse. Charitable help was also restricted and controlled to ensure only the deserving received it. Attitudes towards those who fell into dire straits were based on an individual’s failures and inability to provide for themselves or their families. When parents were faced with inescapable poverty and unable to care for their children the only solution for many was an application for their child to be admitted to an institution. Demands for places led to an increase in philanthropic institutions for children as alternatives to the workhouse. Another aspect of concern identified in the mid-nineteenth century was the increased amount of juvenile crime, associated with the growing number of street children. Harsh punishments were imposed for children who broke the law which were perceived by some influential people as unjust. Campaigns to revise the system for juvenile criminals incorporated the needs of neglected children and expanded the child rescue movement. Throughout the nineteenth century more attention was drawn to the plight of vulnerable children leading to the introduction of child welfare legislation culminating in 1857 with the passing of An Act to make better Provision for the Care and Education of Vagrant Destitute and Disorderly Children and for the Extension of Industrial Schools (Industrial Schools Act).

Two types of institutions were specifically provided for children who were admitted to care through legislation: reformatories, for older children who had committed offences, and industrial schools which accommodated younger children who were on the margins of delinquency, or in need of care. As concern for the treatment of young offenders grew amongst the different factions in the child welfare movement, concern was also expressed about neglected children who were accommodated in reformatories. Young offenders, neglected and abused children were categorized as delinquents in early legislation. Some philanthropists, such as Mary Carpenter, considered these punitive establishments for young offenders, were not the appropriate institution for neglected children.7 Successful campaigns resulted in the ←3 | 4→needs of neglected children incorporated onto the statute. Child rescuers, philanthropists, who came from a different class and culture in the charitable and state agencies, sought out these children who were considered at risk of depravity from the influence of their parents. In general, child rescue isolated children from their families in an environment managed by those from a different class and culture to ensure conformity based on middle-class values.8 Once removed from their parents children were transferred into an institution such as an industrial school until they were 16; here, working-class boys and girls received education, training, and moral regulation, under surveillance. Furthermore, these institutions aimed to shape and control the course of these children’s adult lives by determining their education and employment prospects within a class-centred and gendered ideology.9 In this study I will ask: why were children who were neglected or subjected to physical abuse, or truanted, criminalized?

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 256

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789973747

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789973754

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789973761

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789973730

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18410

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (September)

- Keywords

- Children in care Rescued children Voice of the child

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XVIII, 256 pp., 7 fig. b/w, 6 tables.