Northern Ireland after the Good Friday Agreement

Building a shared future from a troubled past?

Summary

This multi-disciplinary volume owes much to the ongoing debate within Northern Ireland, as an integral part of the conflict transformation process, on how to build a shared and better future for all citizens out of a divided and traumatic past. Drawing on the cross-disciplinary nature of Irish Studies, the authors from the fields of history, literary and cultural studies, politics and sociology explore the legacy of the Troubles and the consequences for Northern Ireland more than twenty years after the Good Friday Agreement.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

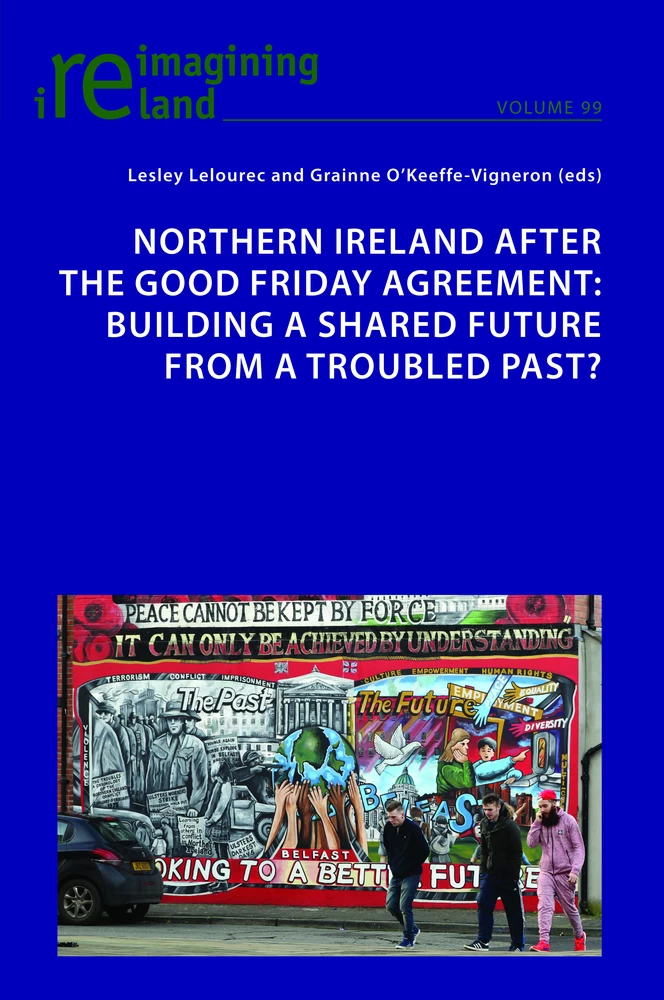

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the authors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- The Collection

- Politics and the People: Shaping and Sharing the Future in Northern Ireland

- Dealing with the Past and Envisioning the Future: Some Problems with Northern Ireland’s Peace Process

- Power-Sharing and Political Stability: Creating and Sustaining a Shared Future in Northern Ireland

- The Memoir-Writing of Former Paramilitary Prisoners in Northern Ireland: A Politics of Reconciliation?

- Loyalist Collective Memory, Perspectives of the Somme and Divided History

- The Ulster Volunteer Force and Dealing with the Past in Northern Ireland

- Postnationalism, Moderate Nationalism and a Shared Northern Ireland: The Case of the SDLP

- Shared Futures or a Rerun of the 1930s? Community, Trauma and Reification in the People of Gallagher Street and Planet Belfast

- ‘A Bright Shiny Police Force Acceptable to All’: Representing the PSNI in Irish Crime Fiction

- Toy Guns and Miniatures: The Kitschification of Conflict in the Paramilitary Museum

- Aftermath – the Role of the Arts in Dealing with the Legacy of Conflict

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Acknowledgements

We would like to begin by thanking all of the wonderful authors who have contributed to this collection; their professionalism and reactivity was much appreciated while bringing this book together.

As ever, Eamon Maher, the editor of the Reimagining Ireland series, was a pleasure to work with and we are delighted to add another volume to this valuable collection. We are extremely grateful to Tony Mason at Peter Lang for being enthusiastic, patient and supportive.

A big thank you goes to Professor Jon Tonge (University of Liverpool) for doing us the honour of writing the foreword.

This publication would not have been possible without the financial support of our University and our research unit (Anglophonies, Communautés, Ecritures (ACE)) at the University of Rennes 2 as well as the expertise of the language faculty’s administrative centre for research.

As we were putting the final touches to this manuscript, we were saddened to learn of the passing of John Hume, the architect of the peace process in Northern Ireland. We were privileged to have met Mr Hume in 2007 when he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Rennes 2.

Last but not least, a special thank you to our husbands and families for their unwavering understanding and support over the years.

Foreword

Lesley Lelourec and Gráinne O’Keeffe-Vigneron deserve huge congratulations for assembling one of the most important recent collections on Northern Ireland. As the country celebrates its centenary, the significance of this volume is that it highlights the intersections of politics, history and culture that have made its hundred years so contested. Contributions from a team of acknowledged world-leading experts in their fields indicate why predictions that Northern Ireland will also enjoy a bicentenary might be brave.

The tone of the book is constructive but realistic throughout. Its historical analyses show that, episodically, cross-community solidarity, challenging sectarian rivalries, is both achievable and celebrated, as Eva Urban’s analysis of theatrical depictions of such bonding in the 1930s amply demonstrates. Equally, however, the volume does not shy away from the difficulties of replicating that famous, but temporary, dissipation of animosities on a permanent basis.

Instead, the book offers a series of assessments of the complexities of power-sharing in a polity which acknowledge the difficulties, given how ultimate constitutional futures cannot be agreed. The contributions offer constructive ways in which disagreement might be handled positively, on the basis of reconciliation, equality, parity of esteem and mutual respect for British unionist and Irish nationalist traditions (and those not aligned to either). Diminishing the binary is tough work. Tim White’s positive assessment of the Good Friday Agreement – a peace deal which, it ought to be remembered, is lauded around the world – indicates his belief that the deal’s framework is one which will allow the reconciliation which consociational deals are often criticised as not providing. On this reading, managing a conflict and reconciling it are not mutually exclusive. Positive power-sharing between representatives of rival ethno-national traditions will impact usefully upon grassroots antagonisms.

Whilst not dissenting, John Brewer’s more sociological analysis questions whether the degree of commitment towards rapprochement among politicians and people is sufficient to make things work. As with all deals, there are winners and losers. In considering the difficulties of the 1998 Agreement’s key architects, the SDLP (Social Democratic and Labour Party), Philippe Cauvet illuminates the difficulties besetting the politics of moderation. The deal instead rewarded, via their release from prison, those ‘combatants’ who had fought the ‘war’. Whilst their recidivism is low, the same can be said for their revisionism, according to Stephen Hopkins’ analysis. The shift from conflict has not led to a fundamental reappraisal among former prisoners of why they participated.

Occasionally, the eclecticism of edited volumes is a weakness. Here, it is a major strength, allowing the contributors to associate the strength of historical memory with contemporary disputes, whilst acknowledging the positive contributions made to community identities by remembrance and learning. Thus, the contributions of Jim McAuley and Aaron Edwards highlight the extent to which loyalist communities and organisations bond via shared interpretations of the past, but also limit how collective loyalist memory can accommodate the different versions of history offered by republicans. Three potential vehicles by which a community or organisation might be understood better by rivals and opponents are books, museums and the arts, which make the considerations of the value of each, by David Clark, Katie Markham and Laurence McKeown respectively, particularly valuable.

The sum of these parts is a wonderful, genuinely interdisciplinary and thoughtful volume, reliant upon evidence not mere assertion. The pleasure in reading lies in its breadth and the capacity of well-informed and astute contributors to challenge lazy orthodoxies, whilst not being controversial merely for the sake of controversy. This is a book which ought to be read by anyone with an interest in Northern Ireland’s past, present and future.

Jon Tonge

Professor of Politics

University of Liverpool

The Collection

In this decade of centenaries, and over twenty years after the signing of the Good Friday agreement, the opening chapter by Lesley Lelourec and Gráinne O’Keeffe-Vigneron assesses how closer Northern Ireland is to becoming a shared - and not shared out - society, with the legacy of the past impacting the present and future. Contending that the consociational system of government has not translated into a shared identity or sense of destiny among the people, this chapter gives a critical overview of the initiatives that have been taken at both the macro and micro level to promote community dialogue, in a political system that tends to perpetuate the nationalist versus unionist dichotomy. While progress has been slow, there have recently been signs of changes in attitudes, a rise in the middle ground in politics and moves towards a more open and inclusive society.

John Brewer considers two models of sharing – the distribution and responsibility model – which could contribute to analysing the differences in ideas about a shared future in Northern Ireland. Brewer explains that the distribution model ‘delivers’ difference (by allocating shares differently) but the responsibility model ‘manages’ difference with a moral obligation to share. Therefore, the responsibility model could be an effective means of dealing with cultural difference. However, this cultural difference, local conditions in Northern Ireland, along with legacy issues and the conflicting memory of the past are making it difficult for Northern Ireland to move forward towards a shared future.

Timothy J. White’s chapter deals with the period after the signing of the GFA and the establishment of a power-sharing executive in Northern Ireland through the introduction of a consociational model. White looks at the attitudes of Catholics and Protestant towards power-sharing and its institutions. Northern Ireland is changing; its future positioning in a post-Brexit United Kingdom remains to be established; the positioning of unionism is evolving as younger Irish protestants increasingly identify as Northern Irish rather than Unionist; a referendum on Irish unity may be getting closer and a slight majority of elected representatives in the 2019 election come from the Catholic community. According to White, power-sharing, with its guarantee of parity of esteem, offers a framework and the key to building a shared future in Ireland where each community can find their place.

The opposition and perhaps lack of understanding between both communities in Northern Ireland has been at the forefront of the problems and has hindered appeasement in Northern Ireland. Through an analysis of the memoir-writing of loyalist and nationalist paramilitary prisoners, Stephen Hopkins considers the experiences of these prisoners during the Troubles in order to gain an understanding of the willingness of reconciliation with the other side and the idea of a shared future. Hopkins has discovered a real lack of understanding between these prisoners of the nature of the conflict in Northern Ireland which he posits complicates any attempt for reconciliation or indeed a shared future. Hopkins concludes through his study of republican and loyalist paramilitary prisoners that they still cling to certain myths and shibboleths of the conflict era and to the notion of republican and loyalist legitimacy. Until a true reappraisal of these myths is carried out, the author questions whether a reconciled or shared future is possible.

Similarly, Jim McAuley discusses Ulster loyalism and the interpretation of the past. This past is claimed to be the possession of the history of one group over another. According to McAuley, through collective memory, Ulster loyalists reproduce a ‘distinct sense of Self and community’ based on an unchanging sense of a ‘common identity and a shared sense of history’. Certain acts of commemoration and remembrance (wall murals, formal commemorations, parades and memorials around the centenary of the Ulster Covenant in 1912, the creation of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and increasingly the battle of the Somme in 1916) allow loyalists to interpret their version of history, history as memory, and maintain the boundaries with the ‘other’ community. This social memory can be transmitted from generation to generation thus reinforcing barriers and division and promoting a shared past among loyalists rather than a shared future within Northern Irish society at large.

The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) has sought to contribute to the continued attempts at dealing with the past in Northern Ireland but Aaron Edwards’ concludes how little progress has been made by this loyalist group thus far. The author suggests that writing about the past can enlighten present and future generations as to why and how people made the choices they did and the consequences of those choices, but that questions need to be continually asked in order to gain a real understanding of past events. Only when the actual human cost of armed conflict in Northern Ireland is understood can it hope to move towards reconciliation and ultimately a shared future.

The Social Democratic and Labour Party’s (SDLP) declining influence in Northern Ireland since 1998 and its incapacity to provide political leadership in Northern Ireland is discussed by Philippe Cauvet. According to the author, this is largely due to the limits and contradictions of the postnationalist analysis which was defended by the late John Hume. Cauvet evokes the weakness of the moderate SDLP faced with the resilience of sectarianism in Northern Ireland and puts forward suggestions as to how this party needs to transform itself in order to find a way out of this impasse and have a role to play in the future of Northern Ireland.

The final chapters of this volume deal with literature and the arts. Eva Urban’s article looks at Green Shoot’s community theatre production 1932: The People of Gallagher Street (2016) and Rosemary Jenkinson’s play Planet Belfast (2013) where the impact of conflict trauma on a divided community in Northern Ireland is staged. 1932: The People of Gallagher Street has as its central theme the reification of community divisions for material and political interests and Planet Belfast deals with the reification of community trauma for personal and political gain. Urban suggests that it is important to remember and learn from past instances of community cohesion and solidarity such as the 1932 outdoor relief strike and the political attempts at sowing divisions amongst people, in order to build solidarity across community lines in Northern Ireland’s post-conflict society.

The fictional representation of the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) in works of crime fiction and how that differs to that of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) is discussed by David Clark. Clark looks at whether the literary representation of the new policing methods and actors conforms to the expectations generated by the creators of the new police service. This chapter also examines how Irish writers have reacted to this new police force. The PSNI was created in the hope that it would become the central element of a proposed ‘shared future’ for the people of Northern Ireland. However, the burden and weight of the past influence the present day and this normal police force still has to operate within an abnormal society.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 248

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789977516

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789977523

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789977530

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789977462

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16551

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (April)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XIV, 248 pp.