Twice a minority: Kosovo Circassians in the Russian Federation

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Content

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Maps

- Figures

- Abbreviations and Terms

- Note on Places, Names, Transliteration and Translation

- On Geographic Settings

- Introduction

- Chapter One Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

- Concept of Minority

- Concept of Boundaries

- Concept of Identification

- Concept of Groupness

- Literature Overview

- Methodological Overview: Ethnography “at Home”

- Chapter Two Migrations and the Kosovo Circassians

- Overview

- From the Caucasus to the Balkans: Circassians in Kosovo

- From Kosovo to the North Caucasus: Kosovo Circassians in Adygheya

- Migration Background: The Kosovo Conflict and the Circassians

- Migration of the 1st Group

- Migration of the 2nd Group

- Migration of the 3rd Group

- Migration of the Kosovo Circassians: Forced, Voluntarily or Co-Ethnic?

- Russian Migratory Legislation and the Kosovo Circassians

- Conclusion

- Chapter Three Language and Identification

- Overview

- Language and Identification in the Balkans/Ex-Yugoslavia

- Language and Boundaries in Kosovo

- Language and the Kosovo Conflict

- Language and Identification in the Soviet Union/Russia

- Language and Boundaries in the North Caucasus

- Conclusion

- Chapter Four Religion and Identification

- Overview

- Religion and Identification in the Balkans/Ex-Yugoslavia

- Religion and boundaries in Kosovo

- Religion and Identification in the Soviet Union/Russia

- Religion and Boundaries in the North Caucasus

- Conclusion

- Chapter Five Culture and Identification

- Overview

- Culture and Identification in the Balkans/Ex-Yugoslavia

- Culture and Boundaries in Kosovo

- Culture and Identification in the Soviet Union/Russia

- Culture and Boundaries in the North Caucasus

- Conclusion

- Chapter Six Gender and Identification

- Overview

- Gender and Boundaries in Kosovo

- Gender and Boundaries in the North Caucasus

- Conclusion

- Summary and Outlook

- Appendices

- App 1: Interview Extr. with A. Dzharimov (1st President Rep. of Adygheya)

- App 2: Interview Extract with a Kosovo Circassian (Male, 45 Years Old)

- App 3: Interview Extract with a Kosovo Circassian (Male, 41 Years Old)

- App 4: Interview Extract with a Kosovo Circassian (Female, 48 Years Old)

- Pictures

- Photos from the Private Archive of Dr. Batiray Özbek

- Photos from the Private Archive of Asfar Kuyek

- Photos from the Private Archive of Gazii Chemso

- Photos from the Private Archive of Marieta Schneider

- Bibliography

Preface

When on August 1st 1998 the first group of the Kosovo Circassians arrived in the Republic of Adygheya of the Russian Federation, I was still a student of the local school in Maykop. But I remember very well the excitement among the Circassians in the republic and around the world concerning the arrival of the Circassians from Kosovo after almost 130 years in exile. The next few weeks were marked by various celebrations, concerts, dancing parties and meetings organized to the honor of the newcomers. At that time I could not have imagined that the history and the narrative of the Kosovo Circassian’s life would become part of my life for several years. After the fall of the Iron Curtain I could observe personally hundreds of the ethnic Circassians from Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Europe, the USA etc. coming to the North Caucasus on short tourist trips, or trying to establish a new life in the historical “homeland.” The reasons, agenda and motivations behind these migrations were different. Nevertheless, through and by these encounters, the notions of identity, culture, history and traditions were challenged and revised among both the “homeland” and the Diaspora Circassians.

The main aim of my project was to reconstruct the identification of the Kosovo Circassians before and after migration to the Caucasus. Benedict Anderson famously noted that all nations are “imagined,” “because the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.”1 The migration of the Kosovo Circassians transferred the “imagined homeland” into the real place of living and the “imagined” community into the real neighbors. What happens when the “imagined” suddenly becomes the everyday reality? Are the Kosovo Circassians exiles, or are they now finally “at home” in the North Caucasus?

←11 | 12→The case of the Kosovo Circassians described in this work indicates that mutual ethnic affiliation is a not a precondition for an unproblematic integration of the co-ethnic migrants into the homeland population. Without doubt other well-known examples of co-ethnic migrations (Russian Jews in Israel, Russian Germans in Germany, and Serbian Croats in Croatia etc.) also indicate the problematic integration of co-ethnic migrants within the “homeland” societies. So one may wonder what is so special about the subjects of this research – the Kosovo Circassians. Previous studies regarding co-ethnic migration mainly dealt with the recognized state minorities which migrated to their respective “homeland” counties. The case of the Circassian migration is in this way unique, because the Circassians do not have a “kin” country of their own. What is referred to as a Circassian “homeland” is part of the Russian Federation. Although the Circassians are the “titular” minorities within the North Caucasian republics of Adygheya, Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachaevo-Cherkessia, one cannot speak of a Circassian nation-state.

1Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (London: Verso, 1991), 6.

Acknowledgments

I am very thankful to everyone who helped me to realize the goals of this project.

I would like to express my deep gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. Stefan Troebst, for his trust in me as a researcher, for his patience and emotional support and for sharing his perspective and deep insight about both research regions, the Balkans and the Russian North Caucasus.

I would also like to thank Dr. Adamantios Skordos for revising my work and for his excellent feedback.

I have also benefited greatly from group meetings and discussions with students and professors at the Global and European Studies Institute (GESI). Thank you all for helping me to stay critical and to sharpen my ideas.

My deepest gratitude goes to members of the Kosovo Circassian community who opened their homes, hearts and life stories to me. I hope that my work reflects your lives to some extent. In particular, I would like to extend my thanks to Batiray Özbek for helping me to establish the contacts with the Kosovo Circassians and for sharing his own unique experience among the community back to Kosovo in the 1970s.

I would like to thank the governmental officials, journalists and historians who granted me interviews and shared their views on the migration of the Kosovo Circassians to the Russian Federation. I also want to acknowledge the professional anthropologists, historians and political scientists, whom I met during my PhD years and who contributed with their fruitful remarks, advices and simply for your interest in my work. Thank you very much Meinolf Ahrens, Dittmar Schorkowitz, Isa Blumi, Fikret Adanir and many others.

This work would have never been possible without the support from my family, my parents and my friends. Thank you. 2

2Artur Tsutsiev, Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014); Dennis P. Hupchick and Harold E. Cox, The Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Eastern Europe (New York: Palgrave, 2001).

Maps

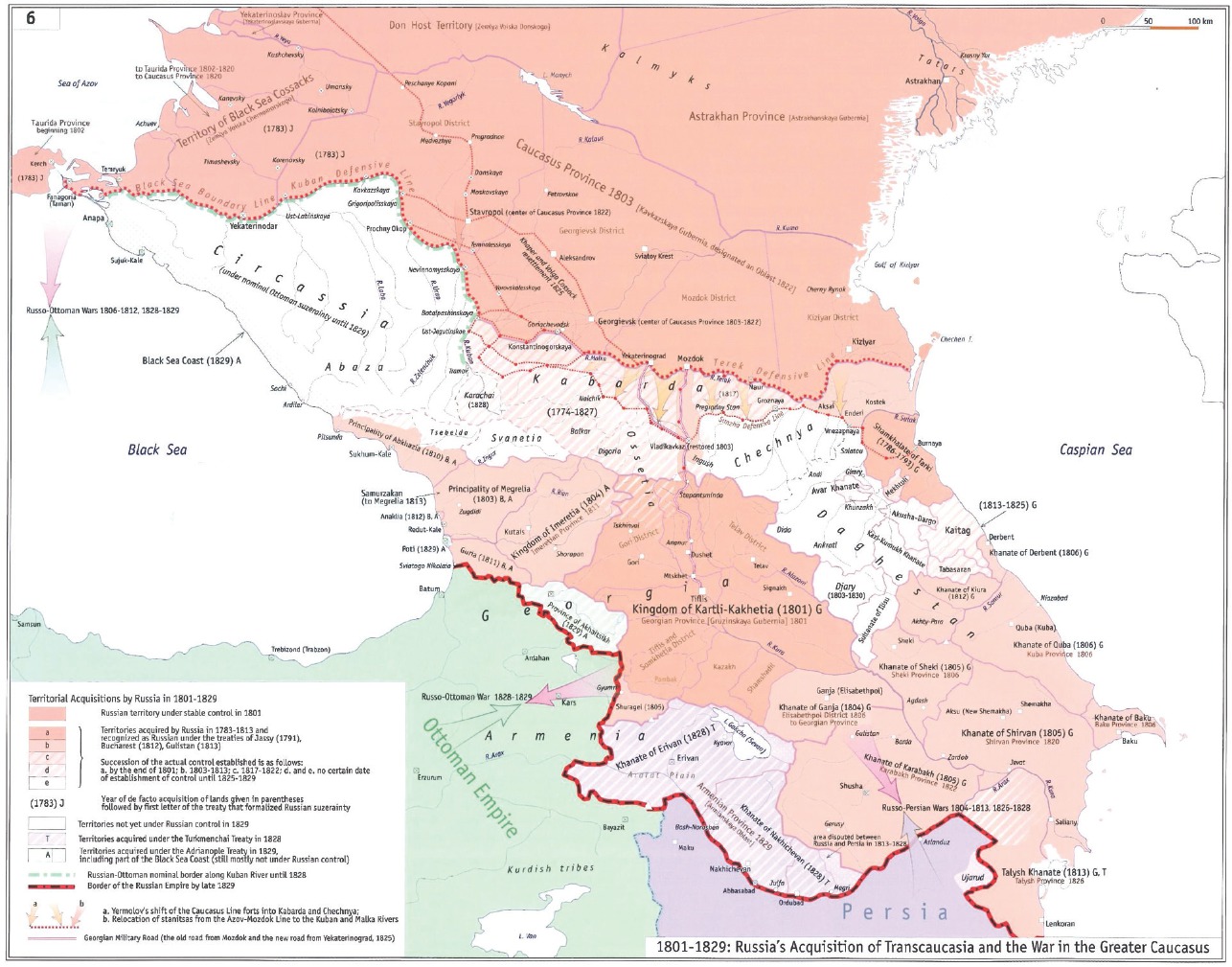

Russia’s Acquisition of Transcaucasia 1801–1829 (Tsutsiev, Atlas, 16).

←15 | 16→

Building a Soviet State 1922–1928 (Tsutsiev, Atlas, 85).

←16 | 17→

The Constitutional Codification of a Hierarchy among Peoples and Territories, 1936–1938 (Tsutsiev, Atlas, 94).

←17 | 18→

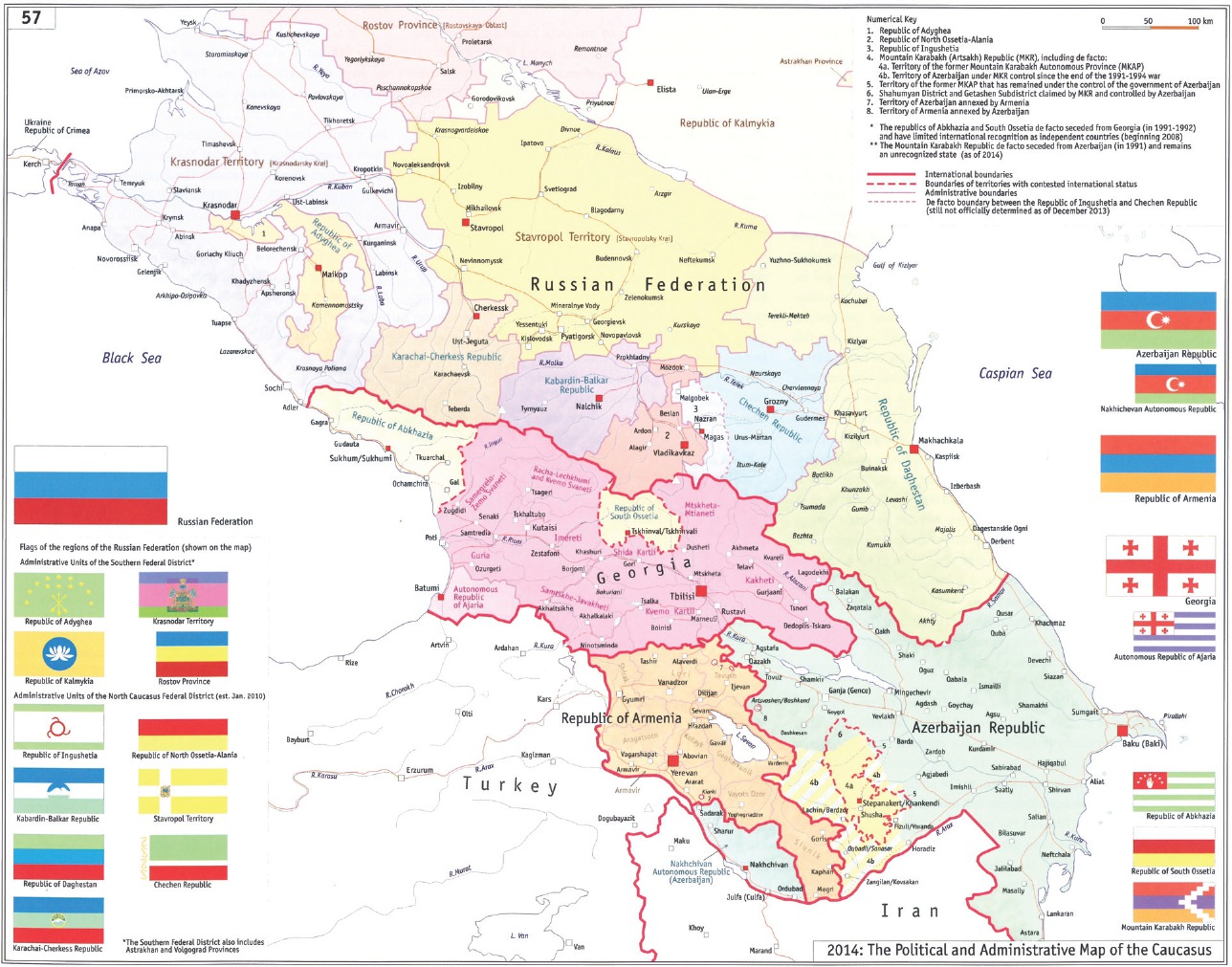

The Political and Administrative Map of the Caucasus 2014 (Tsutsiev, Atlas, 149).

←18 | 19→

The Balkans after the Greek Revolution, 1830 (Hubchick & Cox, Map 32)

←19 | 20→

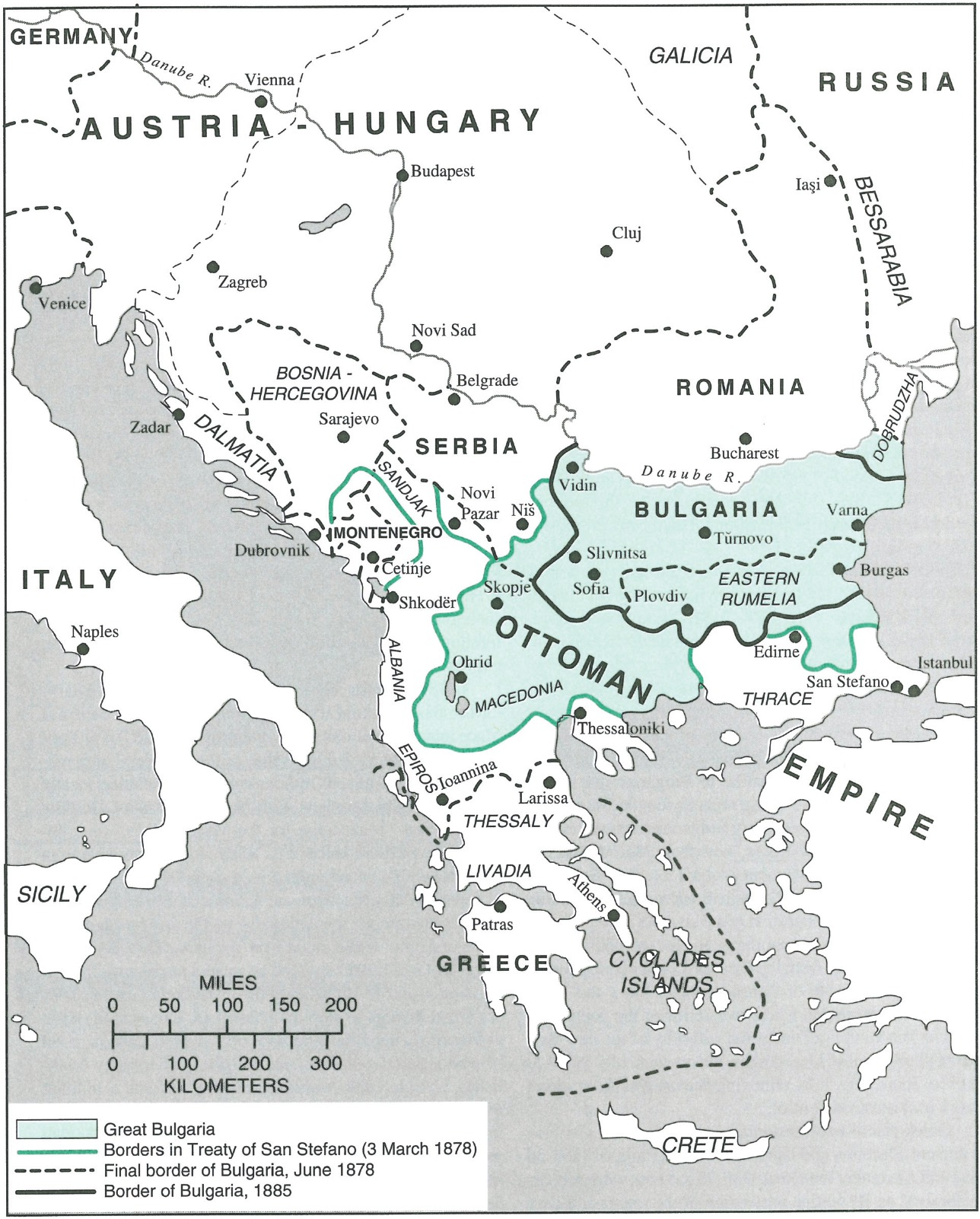

The Balkans, 1878–1885 (Hubchick & Cox, Map 35).

←20 | 21→

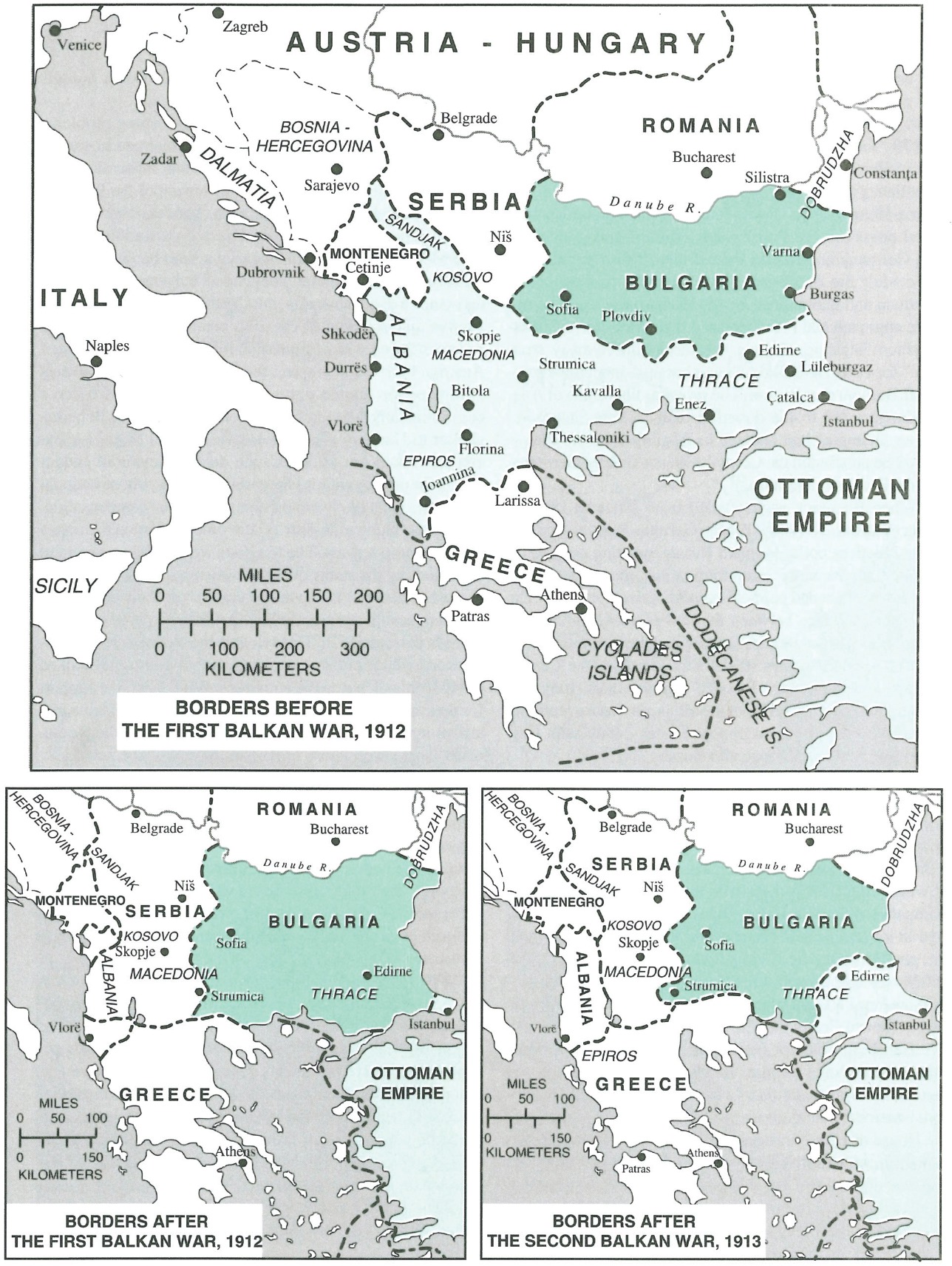

The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913 (Hubchick & Cox, Map 39).

←21 | 22→

The Kosovo Crisis, 1999 (Hubchick &Cox, Map 52).

Figures

Number Topic Page

Figure 1.1.Circassian Villages in Kosovo in the Beginning of the 20th Century.

Figure 1.2.Asfar Kuyok with the 2nd Group of the Kosovo Circassians before Departing Istanbul (Photo Courtesy: Private Archive of Asfar Kuyok).

Figure 1.3.Circassians during the Kosovo Conflict.

Figure 1.4.Article in Izvestiia – “ Russia Will Accept Adyghs from Insurgent Kosovo.”

Figure 1.5.Article in the Newspaper Sovetskaia Adygheya “One Could Hear the Serbian Accent in Adygheya.”

Figure 1.6.Mosque in the Kosovo Circassians’ Village in Adygheya.

Figure 1.7.Circassian Men in Kosovo in 1930s.

Figure 1.8.Circassian Wedding in Kosovo, 1970

Figure 1.9.Circassian Women with Children in Kosovo, 1940s–1950s.

Abbreviations and Terms

Adat tribal common law in the North Caucasus

Adyghe KhabzeAdygh Etiquette or code of norms of traditional behavior

AdygabzeCircassian language

AO(autonomous oblast) – a Soviet territorial-administrative unit designed for smaller ethnic groups, sometimes part of the larger territorial unit (SSR).

Aul a mountain village in the Caucasus

CIS Commonwealth of Independent States: an alliance of former Soviet republics formed in December 1991, including Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Russian Federation, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan. Georgia withdrew its membership in 2008, Ukraine followed in 2018.

Duma the lower house of the Federal Assembly of Russia; the upper house is the Council of Federation

EMERCOM Russian Emergency Situation Ministry

EU /ECEuropean Union /European Community

FMS Federal Migration Service of the Russian Federation

Hijab a veil worn by some Muslim women that conforms to Islamic standards of modesty. The term can refer to any head, face, or body covering

Hodja a Muslim schoolmaster and/or person, who committed pilgrimage to Mecca. An honorable title within the Muslim community

ICA International Circassian Organization

Imama title of a worship leader of a mosque and/or of a Muslim community among Sunni Muslims

Iron Curtaina term to describe the non-physical boundary that separated the Warsaw Pact countries from the NATO countries from about 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991

Kanun traditional Albanian tribal laws

KLA (Alb.: Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosovës or UÇK) – the Kosovo Liberation Army. The ethnic-Albanian nationalist paramilitary union during the Kosovo conflict

Kolkhoz a form of collective farm in the Soviet Union

←25 | 26→Korenizatsiia the policy of indigenization of governing elites in the ethnic republics and smaller territorial units of the Soviet Union

Krai a large territorial unit, subdivided into districts (raions) in the Soviet Union and in the Russian Federation

Mafekhabl’ the village of the Kosovo Circassians in the Republic of Adygheya

Milleta semi-autonomous self-governing religious and cultural com-munity, organized and administrated on the basis of common religious faith in the Ottoman Empire. The term millet in the Ottoman Empire referred to a non-Muslim religious community

M.K.Marita Kumpilova (Schneider)

NAM (Non-Aligned Movement) – is a forum of developing world states that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc

Narodnost’nationality or an ethnic group within the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union

NATOthe North Atlantic Treaty Organization (est. 1949)

Natsiia nation

Natsional’nost’ the ethnic affiliation of people in the Soviet Union

Oblast a Soviet administrative division of land (“province”)

OZNA (Srb.: Odjeljenje za zaštitu naroda or Odeljenje za zaštitu naroda/Department for People’s Protection) – was the security agency of Communist Yugoslavia that existed between 1944 and 1952

Pereselentsy resettlers

Propiska a residency permit and a migration-recording tool both in the Soviet Union and in the Russian Federation

Qur’an (or Koran)is the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be a revelation from God (Allah)

Raion the subunit of oblast’

RSFSRRussian Soviet Federal Socialist Republic, after 1991 the Russian Federation.

Sancak a smaller territorial units of the Ottoman vilayets.

ShariaIslamic religious law, derived from the religious precepts of Islam, particularly the Qur’an and the Hadith

SFR (or SFRY) Yugoslavia (Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia)

SSR Soviet Socialist Republic

←26 | 27→Tanzimat a set of reforms within the Ottoman Empire (1839–1876), aimed to modernize the administration, economy, education, public health of the empire

Umma Islamic community

UNESCOUnited Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

UNHCR the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

USSUnion of Soviet Socialist Republics

Vilayet administrative division, unit or province within the Ottoman Empire.

Note on Places, Names, Transliteration and Translation

The choice of spelling (Albanian or Serbian) of place names in Kosovo is a complicated task, and care has been taken to avoid bias. Often, the decision to use one or another type of writing is understood as a discrete sign of support of one of the conflicting parties. This is not the case in my work. The Serbian variant of place names applied in my work is simply due to practical reasons. The Serbian name Kosovo (instead of Albanian) “Kosova” or “Kosovë” or the full official Serbian version of “Kosovo and Metohija” (or “Kosmet”) is used as the most commonly known and employed in English-language publications and in the most of political and geographical maps of the region. The term “Kosovo Albanians” describes the Albanians in or from Kosovo, as opposed to the Albanians in Albania or Macedonia. The same applies to the “Kosovo Circassians,” it is the Circassians in or from Kosovo.

←29 | 30→No less complicated is the situation with the place and people names within the Russian North Caucasus. I apply the term “Circassians,” the English equivalent to the Turkish and the Serbian (“Cherkess”/“Cerkes”). In general, there are three main denotations of the term “Circasssians.”3 The first and most general include all the native peoples of the North Caucasus. For example, in Turkey, the expression “Circassian” (Turkish –“Cerkes”) describes the descendants of all peoples, who migrated from the North Caucasus (despite their ethnicity) into the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century. The second notion refers to the North-West Caucasians, covering the Adyghs, the Abkhaz, the Abaz, and now extinct Ubyhs peoples. The most restrictive connotation of the term “Circassian,” which is also used in my work, includes solely the Adyghs (composed of various Circassian “tribes” and who speak mutually intelligible dialect of Circassian language –“Adygabze.” The name “Adyghs”/“Adygh” (not Adigh or Adigas/Adig) stays for the self-designation of the Circassian people. In my work I use designations “Adyghs” and “Circassians” as being interchangeable. The terms “Adygheya Circassians,” “Russian Circassians,” “Caucasus Circassians” or “local Circassians” refer to the Circassians in and from the Russian North Caucasus as opposed to the “Kosovo Circassians” or “Diaspora Circassians.” I am aware of the possible bias which lies behind the titles as reproducing the image of the Circassian community as essentially territorially and ethnically bounded. Hence, these terms are applied as practical categories of analysis and reference.

In translating Russian from the Cyrillic to the Roman alphabet I use the Library of Congress system. The same system is used for the Serbian words and names that appear in the text or bibliography. I made an exception, however, for personal names and place names that are already commonly transliterated in different way in English-language literature and maps and as it is the most used in the academic literature on the subject. For example, I use the place name Adygheya (not Adyghea or Adygeia), Prishtina (not Pristina), Maykop (not Maikop), Chechnya (not Chechnia), Skopje (not Skoplje) etc. Accordingly, it is Boris Yeltsin and not Yel’tsin. Some Russian and Serbian words, names and abbreviations that could not be adequately translated, are used in the text transliterated rather than translated. For example, I use Krasnodar Krai, not Krasnodar region. When giving different variants of place-name in different languages, I used the abbreviations “Alb” for Albanian, “Srb” for Serbian and “Circ” for Circassian languages. All translations from Circassian, Russian and German were done by me (indicated in the text as M.K.), unless otherwise stated.

Details

- Pages

- 338

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631854044

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631854051

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631854068

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631852460

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18377

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (April)

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 338 S., 8 farb. Abb., 22 s/w Abb.