Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

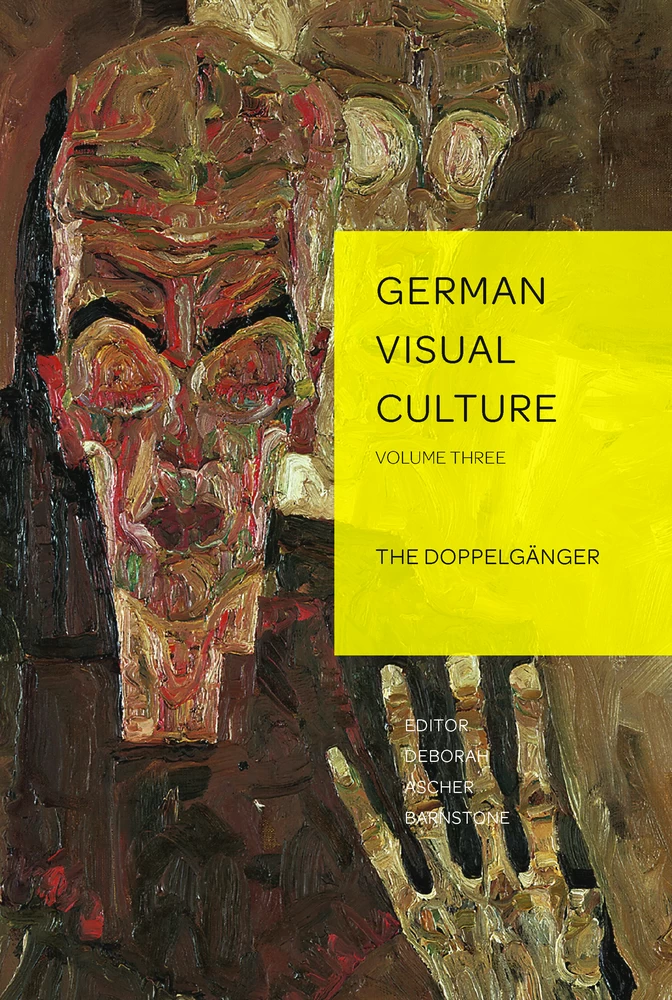

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Deborah Ascher Barnstone - Introduction: The Overlooked Trope of the Doppelgänger

- Part I The Doppelgänger in Painting

- Lori A. Felton - 1 Beyond The Self-Seers: The Creative Strategies within Egon Schiele’s Double Self-Portraiture

- April A. Eisman - 2 From Double Burden to Double Vision: The Doppelgänger in Doris Ziegler’s Paintings of Women in East Germany

- Part II The Doppelgänger in Performance Art

- Paul Monty Paret - 3 Jean Paul at the Bauhaus: Oskar Schlemmer’s Doppelgängers

- Deborah Ascher Barnstone - 4 Seeing Double: The Doppelgänger in Two Interpretations of the Ballet Classic The Nutcracker, by John Neumeier and Marco Goecke

- Nathan J. Timpano - 5 Body Doubles: The Puppe as Doppelgänger in Fin-de-Siècle Viennese Visual Culture

- Part III The Doppelgänger in Film

- Isa Murdock-Hinrichs - 6 The Remake as Double: Space, Media, and the Irrational in Michael Haneke’s Funny Games

- Thomas O. Haakenson and Andrew Felicilda - 7 Melodrama and its Doubles: The Films of Douglas Sirk and Todd Haynes

- Part IV The Doppelgänger as Metaphor

- Maria Makela - 8 Artificial Silk Girls: Rayon as Silk’s Double in Weimar Germany

- Brigitte Marschall - 9 X-ray Images as the Body’s Double: From The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann to the Holy Mountain in the Life and Death of Christoph Schlingensief

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series Index

Lori A. Felton – Beyond The Self-Seers: The Creative Strategies within Egon Schiele’s Double Self-Portraiture

Figure 1.1 Egon Schiele, The Self-Seers I (Double Self-Portrait), 1910.

Figure 1.2 Egon Schiele, Prophets (Double Self-Portrait), 1911.

Figure 1.3 Egon Schiele, The Self-Seers II (Death and Man), 1911.

Figure 1.4 Anton Trčka, Schiele standing before “Encounter,” 1914–1915.

Figure 1.5 Egon Schiele, Transfiguration (The Blind II), 1915.

April A. Eisman – From Double Burden to Double Vision: The Doppelgänger in Doris Ziegler’s Paintings of Women in East Germany

Figure 2.1 Doris Ziegler, Brigade Rosa Luxemburg – Eva (one panel from a pentaptych), 1974/75, mixed technique on hard fiber, 125 × 80 cm (Lindenau Museum Altenburg).

Figure 2.2 Doris Ziegler, Mother and Daughter (Mutter und Tochter), 1982/83, oil on hard fiber, 127 × 94 cm (Galerie Junge Kunst, Frankfurt/Oder).

Figure 2.3 Doris Ziegler, Self Portrait with Mirrors (Selbstbildnis mit Spiegeln), 1985, mixed technique on hard fiber, 90.5 × 68.5 cm (Privatsammlung).

Figure 2.4 Doris Ziegler, Self with Son (Selbst mit Sohn), 1987, egg tempera and oil on hard fiber, 169 × 115 cm (Klassikstiftung Weimar, Neues Museum Weimar).

Figure 2.5 Doris Ziegler, I Am You (Ich bin Du), 1988, 170 × 170 cm, mixed technique on hard fiber (property of the artist/on permanent loan to the Klassikstiftung Weimar, Neues Museum Weimar). ← vii | viii →

Paul Monty Paret – Jean Paul at the Bauhaus: Oskar Schlemmer’s Doppelgängers

Figure 3.1 Oskar Schlemmer, Untitled (Self-Portrait at the Prellerstrasse studio in Weimar), 1925. Gelatin silver print. J. Paul Getty Museum.

Figure 3.2 Oskar Schlemmer, Poster for Das Triadische Ballett, 1922. Watercolor, paint and ink.

Figure 3.3 Oskar Schlemmer, Gold Sphere from The Triadic Ballet, c.1923 From Die Bühne im Bauhaus (Munich: Albert Langen, 1925), 31.

Figure 3.4 Oskar Schlemmer, The Abstract, 1927. Gelatin silver print with retouched highlights. From Das Triadische Ballet. Regieheft für Hermann Scherchen. Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin. Photo: Marcus Hawlik.

Figure 3.5 Margrit Baumeister, “Willi Baumeister and Oskar Schlemmer in Frankfurt am Main,” c.1929. Photograph courtesy of the Archiv Baumeister im Kunstmuseum Stuttgart.

Deborah Ascher Barnstone – Seeing Double: The Doppelgänger in Two Interpretations of the Ballet Classic The Nutcracker, by John Neumeier and Marco Goecke

Figure 4.1 Clara and the Nutcracker dancing together. The image is typical of the idiosyncratic movement Goecke uses. Scapino Ballet Rotterdam.

Figure 4.2 Clara amidst the piles of nuts. Scapino Ballet Rotterdam.

Figure 4.3 Clara and the Nutcracker in their erotic duet. Scapino Ballet Rotterdam.

Figure 4.4 The use of Drosselmeier’s hat to double his presence on the stage. Scapino Ballet Rotterdam.

Figure 4.5 Clara dancing “Snow”. Scapino Ballet Rotterdam. ← viii | ix →

Nathan J. Timpano – Body Doubles: The Puppe as Doppelgänger in Fin-de-Siècle Viennese Visual Culture

Figure 5.1 Oskar Kokoschka, Die Erwachenden (The Awakening), seventh color lithograph from Die träumenden Knaben (The Dreaming Youths), 1907, printed in 1908. Vienna, Wien Museum.

Figure 5.2 Egon Schiele, Selbstdarstellung mit gestreiften Ärmelschonern (Self-Portrait with Striped Armlets), 1915. Vienna, Leopold Museum.

Figure 5.3 Egon Schiele, Sitzendes Paar (Seated Couple), 1915. Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina.

Figure 5.4 Oskar Kokoschka, Mann mit Puppe (Man with Doll), circa 1922. Berlin, Nationalgalerie.

Figure 5.5 Oskar Kokoschka, Die Windsbraut (The Bride of the Wind/Tempest), 1913–1914. Basel, Kunstmuseum.

Isa Murdock-Hinrichs – The Remake as Double: Space, Media and the Irrational in Michael Haneke’s Funny Games

Figure 6.1 “Can I get anyone anything?”

Figure 6.2 “Open the windows, will you. We need to let some air in.”

Figure 6.3 “That’s cheating!”

Tom Haakenson and Andrew Felicilda – Melodrama and its Doubles: The Films of Douglas Sirk and Todd Haynes

Figure 7.1 Still from All That Heaven Allows. Carey Scott is trapped by her children and framed restrictively by the mirror in her bedroom.

Figure 7.2 Still from All That Heaven Allows. Cary Scott receives a television from her children for Christmas, the ideal gift for the “lonely widow.” ← ix | x →

Figure 7.3 Still from Far From Heaven. Cathy Whitaker is framed by the mirrors in her bedroom and by her daughter Janet’s admiring stare, a framing that suggests Cathy’s increasing confinement in her roles as wife and mother.

Figure 7.4 Still from Far From Heaven. The ever-present Mrs Leacock and her photographer sidekick capturing Frank and Cathy in a candid shot for the local newspaper.

Figure 7.5 Still from Far From Heaven. Frank pressed against his office desk and in the arms of a male lover.

Figure 7.6 Still from Far From Heaven. Frank’s young, new lover interest waits while Frank is on the phone with Cathy, discussing divorce proceedings and childcare issues.

Maria Makela – Artificial Silk Girls: Rayon as Silk’s Double in Weimar Germany

Figure 8.1 “Atlas” silk rayon skirt, circa 1917. Die Dame 44, No. 13 (Mid-April 1917), 14; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, photo Dietmar Katz.

Figure 8.2 Advertisement for “Glanzstoff” rayon products. llustrierte Textil-Zeitung 3, No. 5 (29 Jan 1927), 5; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, photo Dietmar Katz.

Figure 8.3 Marlene Dietrich for Bemberg rayon products, 1930. Mitteilungen der J.P. Bemberg Aktiengesellschaft 3 (August 1930), 1.

Figure 8.4 1929 display of Bemberg Gesundheitswäsche (rayon health lingerie) in Max Kühl’s Berlin lingerie store. Mitteilungen der J.P. Bemberg Aktien-Gesellschaft 2, No. 8 (1 August 1929), 9. ← x | xi →

Figure 8.5 Only natural silk is true elegance. Only natural silk is silk. Die Dame 56, No. 11 (Second February Issue 1929), 41; Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, Photo Dietmar Katz.

Figure 8.6 Bemberg silk, the spitting image of natural silk. Erich Greiffenhagen, ed., Kunstseide vom Rohstoff bis zum Fertigfabrikat. Für den Bedarf des Textilkaufmanns (Berlin: L Schottlaender & Co., 1928).

Birgitte Marschall – X-ray Images as the Body’s Double: From The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann to the Holy Mountain in the Life and Death of Christoph Schlingensief

Figure 9.1 A Church of Fear vs the Alien Within. Stage installation of Schlingensief’s Fluxus Oratory in the German Pavillion, Monstrance. Photo, Roman Mensing, artdoc.de.

Introduction: The Overlooked Trope of the Doppelgänger

The essays in German Visual Culture: The Doppelgänger explore the phenomenon of the double in multiple aspects of German visual culture. The Doppelgänger, or double, is an ancient and universal theme that can be traced at least as far back as Greek and Roman mythology but is particularly strong in German literature and culture since the Romantic Movement in the eighteenth century. Literally the “double walker” or “double goer,” the Doppelgänger is an exact duplicate of the living person, indistinguishable from the original. It can be a true double, twin, mirror image, portrait, split personality, alter ego, mechanical doll, or ghostly shadow. The double historically represented evil, misfortune, and death, presaged them, or forecast supernatural phenomena but also represented the dual nature of human beings and human society as well as the split between reality and fantasy contained in every artwork. Since the advent of modern psychology, artists, writers and filmmakers increasingly use the double to symbolize mental and spiritual trauma and struggles with identity and the ego.

Details

- Pages

- XI, 273

- Publication Year

- 2016

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034319614

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035308181

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035395815

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035395822

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0818-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (April)

- Keywords

- German visual culture material culture photography film media magic mountain weimar german

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2016. XI, 273 pp., 37 coloured ill., 8 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG