At the Origins of Islam

Muḥammad, the Community of the Qur’ān, and the Transformation of the Bedouin World

Summary

This book offers a new and bold explanation for these momentous events. It investigates the growth of a community of believers around their prophet in an Arabian oasis before looking at how their interactions with surrounding nomads set in store truly transformative developments. These developments took on a deeper significance given wider changes witnessed in the late antique Near East, which created the context for the earthshattering events of the seventh century.

At the Origins of Islam: Muḥammad, the Community of the Qurʾān, and the Transformation of the Bedouin World unites the near and far horizons of early Islam into one story. It embraces a broad range of sources and comparative evidence to set new courses in the study of Late Antiquity and early Islam.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction A World Made Anew …

- Chapter 1 Muḥammad at Medina

- Chapter 2 The Community of the Qurʾān

- Chapter 3 Approaching the Bedouin

- Chapter 4 Muḥammad and the Neighbouring Desert Arabs

- Chapter 5 The Origins of the Islamic State

- Chapter 6 The Near East before Muḥammad

- Chapter 7 The Transformation of the Bedouin World

- Chapter 8 Arabia in the Last Great War of Antiquity

- Conclusion The Accident of Late Antiquity

- Bibliography

- Index

Preface

Few who came of age in the wake of the 9/11 attack on the Twin Towers in New York have been able to escape discussion of Islam. Popular discourse on one of the world’s great religions varies from condemnation of an ideology allegedly dedicated to bloodshed, to plaintive cries that Islam is nothing but a deeply misunderstood religion of peace, some of whose adherents have simply found themselves the victims of geopolitical trends beyond their control. These irreconcilable perspectives speak to an underlying vacuum of understanding. To a materialistic Western World that has become all but totally post-Christian – and consequently closed-off from the kinds of spiritual and moral concerns that motivated previous generations – seeing men willingly give up their lives for their faith, or quiet, veiled women accept a life of apparently bland domesticity, can indeed seem alien and incomprehensible. Islam is, moreover, most perfectly expressed in a script that can appear baffling and complex, whose incantations are uttered in desert lands that seem wholly inhospitable to European and American eyes accustomed to the gentle greenery of more clement climes.

Islam is the West’s original ‘other’. Some would say that the end of the Cold War and the outbreak of the War on Terror merely returned the West to facing the challenge of its historical rival civilisation. From the First Crusade to the later wars against Ottoman expansion in the Balkans, the politically fragmented world of what used to be called Christendom found unity and an identity in fighting against what it held to be the existential threat of Islam. Even as the rise of China and a resurgent Russia starts to dominate the attention of Western policymakers, the current growth of Islamic extremism in Africa, and its persistence in Central Asia and the Middle East, may ensure that this historical enmity will continue to shape the future.

It can come as a surprise, therefore, to learn that the roots of Islamic civilisation are far closer to the origins of the West’s own than this perception ←ix | x→of irreconcilable, atavistic rivalry can suggest. It certainly came as something of a surprise to me. I first encountered serious study of Islamic origins as a final-year student of Classics – a subject that used to be proud of its role as a standard bearer of Western Civilisation – when focusing on the period now known as Late Antiquity and the fall of the Roman Empire. Late Antiquity, a period roughly stretching from the beginning of the fourth century ad to the end of the eighth century, usefully breaks down disciplinary divides and highlights historical influences and continuities that the changes of which they were also a part can all too often conceal. This periodisation, which focuses attention on how difficult it can be to speak of such hard-and-fast concepts as ‘the’ fall of Rome (as well as ‘the fall’ of Rome), also helps to bridge the gap between the mutually exclusive study of the ancient and medieval worlds, as well as overcoming the separation of the study of the three great monotheistic faiths into the hands of specialists and faithful adherents.

I tried to address the value of a broad, late antiquarian approach to studying, in particular, the nature of the seventh-century Islamic Conquests in a previous book, The Two Falls of Rome in Late Antiquity: The Arabian Conquests in Comparative Perspective.1 That publication grew from an Oxford M.Phil thesis, which sprang from a sense that the sources that are used to reconstruct the Germanic invasions of the Roman West in the fifth century, and those that can be used to retell the story of the Islamic Conquests of the seventh, reveal similar phenomena but have been read in entirely different ways owing to the conventional disciplinary divides between Islamic Studies on one hand and the study of Roman and early medieval European history on the other. The M.Phil led to further study and to a D.Phil thesis that remained true to harnessing the value of a cross-disciplinary, late antiquarian approach, whilst also delving far deeper into the sources of the Islamic tradition and being unafraid to acknowledge the particularities of Islam’s Arabian origins.

At the Origins of Islam: Muḥammad, the Community of the Qurʾān, and the Transformation of the Bedouin World is fundamentally the product ←x | xi→of this D.Phil. It begins with an Introduction that establishes the rise of Islam as a pivotal moment in world history before embarking on an exploration of the historiographical issues involved in studying the subject, which is necessarily lengthy given the complexities involved. Chapter 1 looks at Muḥammad and his community in Medina, a quest continued in Chapter 2. These chapters find that the first ‘Muslims’ were a very specific constituent of the Prophet’s community, whose nature and identity is explored in Chapters 3 and 4. Chapter 5 tries to reconstruct the process through which nomad and sedentary united to form the first Islamic state. Chapters 6, 7 and 8 then raise their eyes to what this book calls the ‘far horizon’ of Islam’s origins, Late Antiquity, showing how developments in inner Arabia ultimately depended on far broader processes of change to have the earthshattering impact that they eventually did.

In addition to forcing one to address issues like the original audience of the Qurʾān, or the actual nature of Roman frontier policy in the Near East, the sixth and seventh centuries also provoke profound reflection on what makes and moves history in far broader terms. We see the power of abstract, otherworldly and ideological concerns on the human mind in the impact of the Prophet’s preaching. The decisions and idiosyncrasies of powerful individuals – Muḥammad, Justinian or Khusro – can determine the fate of states and the lives of millions, whilst whole societies find themselves shaped by the material reality of their environment, conditioned to act in ways beyond their immediate control. War appears as perhaps the most significant force for change, dislocating established structures and assumptions and even leading to the rapid evolution of new identities and novel ways of looking at the world. It both destroys and makes anew.

Above all, At the Origins refuses to shy away from addressing major issues and making bold claims. Knowledge cannot rely on timidity to advance. The fascinating problems posed by the origins of Islam demand an expansive, daring and innovative approach. The subject already incites passionate debate, and I hope that this book at least succeeds in adding fuel to this scholarly fire, challenging received wisdom, establishing new parameters of intellectual exploration, and engaging fresh minds in the study of a period as stimulating as it can be obscure.←xi | xii→

If this book can also do a little to improve understandings of how movements that continue to shape the world are rooted in a certain historical context – creating notions open to constant interpretation from concepts seen as eternal and everlasting – then it can also be said to combine its ambition with a hint of a higher cause.

Acknowledgements

I am immensely grateful to a number of people who helped to make this book a reality. My original D.Phil supervisors were Robert Hoyland and Mark Whittow. Even though we may have come to adopt different perspectives on issues like Fred Donner’s ‘Believers Thesis’, Robert’s deep knowledge of the subject and perceptive insights helped to expand my horizons before he left Oxford for New York. His contribution to the field is barely rivalled in his generation and I am sorry that my time learning from him first hand was not longer.

Far greater sorrow, however, must be reserved for the tragic loss of Mark Whittow. Mark was the very model of the Oxford gentleman and scholar. Dapper, refined, ceaselessly jolly and, above all, committed to a recognition of the importance of breadth in historical knowledge – in an age when many other academics seem myopically obsessed with minutiae – Mark’s death in a car accident just before Christmas 2017 was a loss to the world. I never knew him as well as some others of his students, being originally something of a refugee from Cambridge, and then distracted by interests beyond the ivory towers throughout my postgraduate years, but it was Mark’s mentorship that set me on the path of concentrating, above all, on Arabian nomads. It was also his encouragement that kept the boundaries of my thesis broad. I am deeply thankful to him.

I was subsequently supervised by Phil Booth and Christian Sahner. Phil had taught me at Cambridge and is a master of all things late antique and Christian continued the quest of opening my eyes to the complexities of Islamic history. They both refined my thinking, were patient with my errors and oversights and indulged my ideas. They graciously pushed me on and helped to bring the project to an eventual conclusion. Like my other mentors and influences, they of course bear no responsibility for any inaccuracies or failures of interpretation in what follows. I thank them both.

Many others deserve credit for helping to make the years spent at Oxford and working on what became this book a golden age. I am ←xiii | xiv→profoundly lucky to have friends like Matt, John, Toby, Chris, P. G., Dan, Marco and Aiden, many of whom often visited the city from afar to keep me company and the local publicans rich. Michael, good in name and nature, deserves a special mention for his willingness to entertain my historical musings on many an adventure in the wild and for his constant, brotherly friendship. At Oxford, I was, and remain, warmly grateful for the cheery company of George (‘the Dean’), Michael, Rob and David, not least for many a merry night when we discussed the vagaries of history under the avuncular eyes of the indomitable Lincoln College barman, SF. Lincoln itself of course deserves my thanks, as does the A. G. Leventis Foundation for funding my first two years of study. Thanks are also naturally due to Lucy and her team at Peter Lang for steering the manuscript through peer review and to publication.

There are, finally, others I could name, but sometimes the memories, and the thanks, are all the sweeter – and some bittersweet – for being preserved in a place more intimate than the page.

←xiv | xv→

Introduction

A World Made Anew …

God effected that the whole world should be illumined from the very beginning by two eyes, namely by the most powerful kingdom of the Romans, and by the most prudent sceptre of the Persian state …

– Khusro Parvez, Shah of Persia, to Maurice, Emperor of Rome, as preserved in the History of Theophylact Simocatta, 4.11.21

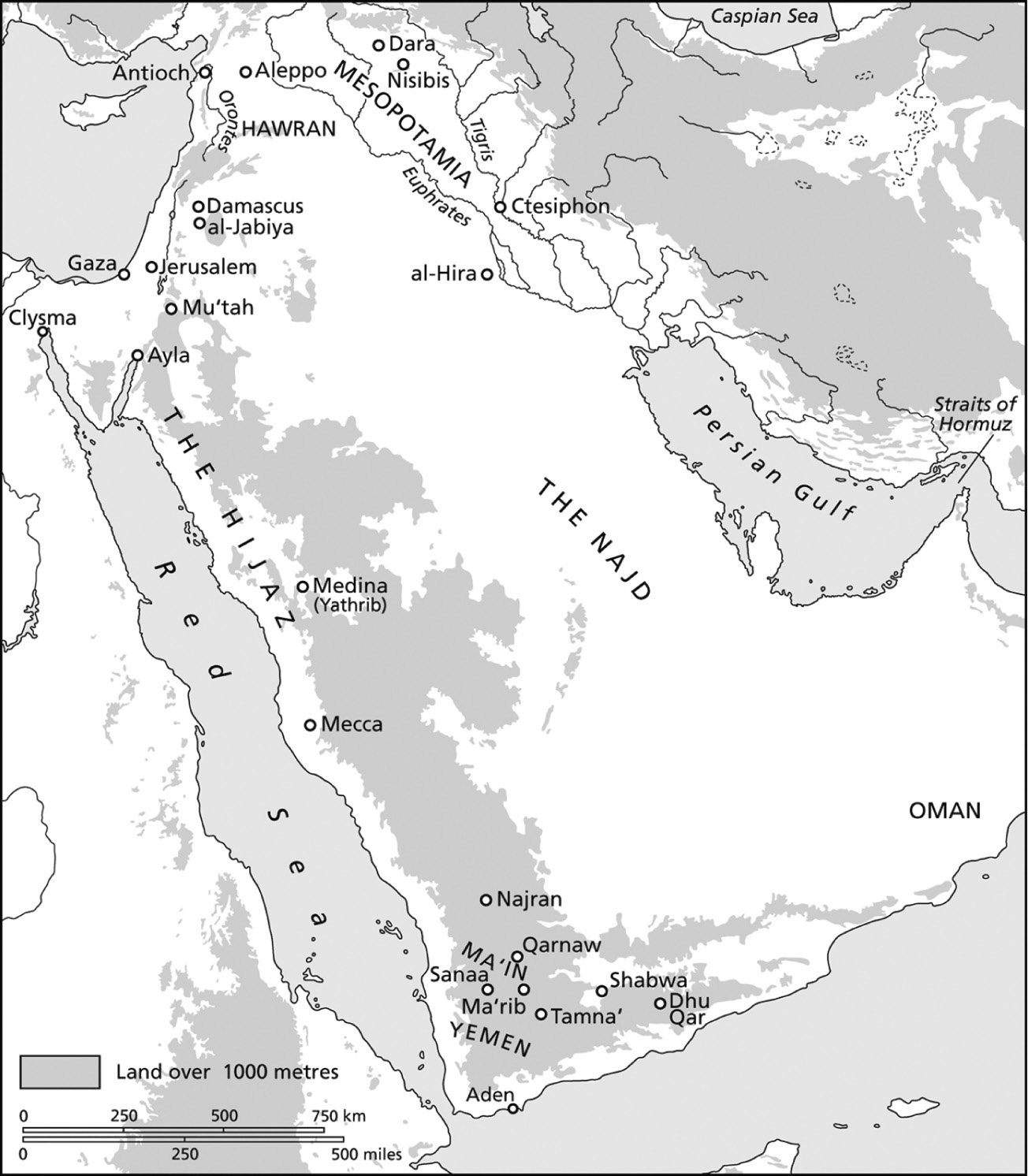

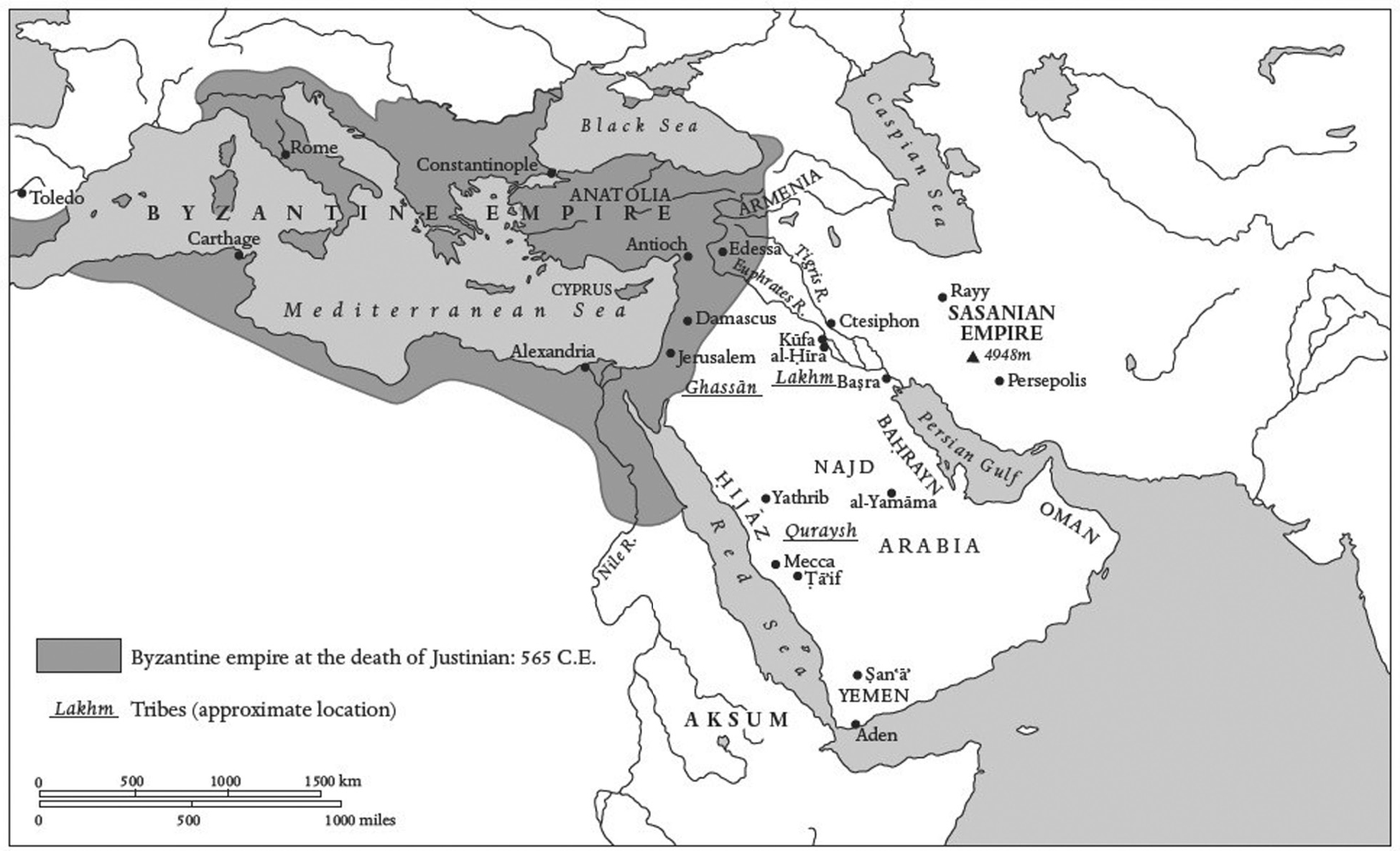

Khusro had every right to believe that the situation he described was sanctioned by powers not entirely of this world when he wrote these words to his imperial rival. From his seat at the Persian capital of Ctesiphon on the banks of the Tigris – the river that had given life to the earliest of human civilisations – he looked out upon a world that was indeed dominated by two great powers. It had been thus for so long that it simply must have been the natural order of things. He himself was the ruler of a venerable empire and the spiritual heir to the world-conqueror Cyrus the Great, who had first made Persia a world power a millennium before Khusro. The Persian shah’s domain stretched from the Great Steppe, through the Iranian plateau, across the Zagros Mountains and down into the Fertile Crescent, where Persia met Rome on the upper reaches of the Tigris, amidst the hilly and difficult terrain of the Taurus and Caucasian mountain ranges.

Rome may have lost her western provinces to the depredations of powerful barbarian peoples in the century previous to Khusro’s letter, but Maurice was still master of a vast and powerful empire. Rome had ruled lands as diverse and distant as the coastal strip of North Africa, the Balkans, highland Anatolia, the Levant and the breadbasket of empire that was Egypt for half a millennium. Her legions, though occasionally humbled, ←1 | 2→had nonetheless continued to guarantee the security of Constantinople’s subject peoples through centuries of warfare with hosts of threatening foes, not least the armies of Persia, Rome’s only real rival for Eurasian dominance. As is all too readily apparent when reading the History of Theophylact Simocatta – written in a style deliberately aping an approach to history that speaks to the self-conscious antiquity and greatness of the author’s civilisation – the men who ruled the world of the sixth century ad saw themselves as the custodians of an eternal, all-powerful and divinely ordained world order destined to last until the very end of days.

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 274

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800796591

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800796607

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800798090

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781800796584

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18967

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (April)

- Keywords

- Late Antiquity Islam Nomadism At the Origins of Islam James Moreton Wakeley

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2022. XVI, 274 pp., 2 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG