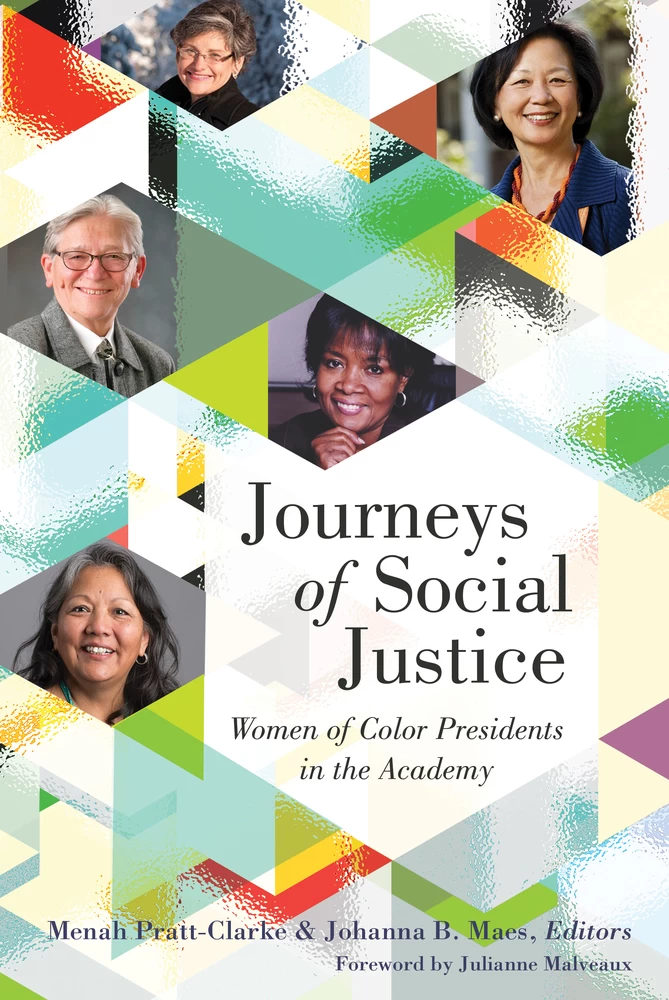

Journeys of Social Justice

Women of Color Presidents in the Academy

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Foreword (Julianne Malveaux)

- Reference

- Acknowledgments

- Menah Pratt-Clarke

- Johanna B. Maes

- Part I: Setting the Stage

- 1. Introduction to Journeys of Social Justice: Women of Color Presidents in the Academy (Menah Pratt-Clarke / Johanna B. Maes)

- Opening Reflections from Menah Pratt-Clarke

- Opening Reflections from Johanna B. Maes

- References

- 2. Reflections from Below the Plantation Roof (Menah Pratt-Clarke)

- Introduction

- The Invisibility of Women of Color Presidents

- The Scholarship on Women of Color Presidents

- The Transdisciplinary Applied Social Justice model

- Conclusion

- References

- 3. The Adobe Ceiling over the Yellow Brick Road (Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs)

- The Adobe Ceiling

- Mid-Career Muddle

- Social Class Captives

- Closing Thoughts and the Yellow Brick Road

- References

- 4. The Labyrinth Path of Administration: From Full Professor to Senior Administrator (Irma McClaurin / Victoria Chou / Valerie Lee)

- Irma McClaurin

- Victoria Chou

- Valerie Lee

- Conclusion

- References

- Part II: On the Stage

- 5. A View from the Helm: A Black Woman’s Reflection on Her Chancellorship (Paula Allen-Meares)

- The Journey to Chancellor

- A Chancellor’s Profile

- Why UIC?

- Framing Higher Education

- Framing at UIC

- My Affair with Diversity

- Facing Challenges

- Changes in University Leadership

- Budget and Facilities

- Faculty Unionizing

- Sibling Rivalry (UIUC/UIC)

- Chancellor’s Residence

- Lessons Learned

- Conclusion

- References

- 6. Reflections about African American Female Leadership in the Academy (Menah Pratt-Clarke / Jasmine Parker)

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Preparation and Performance

- Perseverance

- A Commitment to Social Justice

- Conclusion

- References

- 7. Re-envisioning the Academy for Women of Color (Phyllis M. Wise)

- Introduction

- Leadership

- Women and Minorities in STEM

- Diversity

- Conclusion

- Reference

- 8. Reflections about Asian American Female Leadership in the Academy (Menah Pratt-Clarke)

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Foundation and Preparation

- Entrepreneurial Spirit

- Commitment to Diversity

- Experiencing Racism and Sexism

- Conclusion

- References

- 9. My Climb to the Highest Rung (Cassandra Manuelito-Kerkvliet (Diné))

- My Navajo Foundation

- From Humble Beginnings

- Ascending to the Top

- Tapping Traditional Wisdom

- Melding a Distinctive Leadership Style

- Release, Respite, and Breathing Space

- 10. Reflections about Native American Female Leadership in the Academy (Menah Pratt-Clarke / Johanna B. Maes / Melissa Leal / Tanaya Winder)

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Leadership and Native American Culture

- Hózhó: Beauty and Balance

- The Philosophy of K’é and Relationships

- Conclusion

- References

- 11. Journeys into Leadership: A View from the President’s Chair (Nancy “Rusty” Barceló)

- The View

- My Journey: The Backstory

- Where We Go from Here

- 12. Thriving as Administrators at America’s Land Grant Universities (Waded Cruzado)

- References

- 13. Reflections about Latina/Chicana Leadership in the Academy (Johanna B. Maes)

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Latinas in Education

- Latinas and Family Connections

- Latinas and Spirituality

- Latinas as Professionals

- Latinas in Academia

- Latina Leadership

- The Trailblazers: Rusty Barceló and Waded Cruzado

- Intersectionality

- Servant and Transformational Leadership

- Conclusion and Counterstorytelling

- References

- 14. Closing Reflections (Menah Pratt-Clarke / Johanna B. Maes)

- Menah Pratt-Clarke

- Johanna B. Maes

- Contributor’s Biographies

- Series index

What does a college president look like? For many the answer is White, male, over 55, and perhaps bespectacled. His hair, in the image, might be graying, or it might be a hearty headful of bouncing brown hair. But he’d be White. He’d be male. He’d never have anyone say to him, “You don’t look like a college President.” Unfortunately, despite the many cracks in the glass ceiling of leadership in politics, culture, and higher education, the prevailing and stereotypical image of a leader remains that of a White male. If someone were asked to pick a leader out of a lineup, a White male would likely be first chosen, with a woman of color likely chosen last.

That reality hit me upside the head on the day I once sat outside a meeting room, appropriately adorned in designer knit, and a colorful kente scarf. I was on my phone, tapping away, when from nowhere a black coat was plopped on a table and I was asked for a coat check tab. I looked up to find a White woman, clad in an almost identical designer knit, glowering down at me, when I realized that I actually was sitting near the unattended coat check area. I was silent for a few seconds, counting long enough to swallow the caustic comment on the tip of my tongue. Saved by a colleague! Another woman, African American, walked up with a big smile, greeted me by my first name, and turned to the coat-toting woman and said, “I guess you haven’t met Dr. Malveaux.” She went on to say that the meeting was on the first floor, not the lobby, of the hotel and there was a mistake with an earlier communication. The coat-toter did manage to put her hand out as we greeted each other, but she didn’t refer to her faux pas, and neither did I. You don’t look like a college president.

Stereotypes allow some to define what a college president looks like, what a leader looks like, and what a change agent looks like. Stereotypes need to be shattered, but also examined. What does it cost for a woman to live inside somebody else’s stereotype? This important volume, Journeys of Social Justice: ← ix | x → Women of Color Presidents in the Academy examines these myriad of questions. It dares discuss higher education leadership by weaving together the narratives of women who have led, and who have studied leadership. The volume addresses the ways that women of color leaders must both be present in their cultures and be fluid enough to use (and transcend) culture to strengthen their leadership. This book offers personal stories and policy prescriptives. And, most importantly, it inspires aspirational women of color, and those who must work with them, to transform the culture of higher education so that diverse leadership is far more enthusiastically welcomed.

For me, reading this was like listening to Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly,” listening to sisters “strumming my pain with (their) fingers, singing my life with (their) words.” These essays, reflective, bounce off each other, and bounce off the experiences that I, and so many women of color in higher education leadership, have had in the academy. An excerpt from Paula Allen Meares in chapter five reveals this reality:

During my chancellorship, some were surprised when they met me. Some thought I would be taller. Others were surprised that I was the chancellor: I just didn’t look like what they had envisioned. Once, someone asked if I were the secretary, and another asked, “Where is the Chancellor?” The so-called typical profile of a chancellor/president/vice president is still majority male, at least six feet tall, and graying or balding. The typical chancellor possesses a disciplinary background—medicine, bench science, business, law, or engineering.

In chapter four, Irma McLaurin writes of the “constant scrutiny” that women of color president’s experience. Those who scrutinize really ought to be singing praises of awe. Every President has to do her job well, and that alone requires juggling. There is pressure to raise money, and a multitude of constituencies—board, faculty, staff, community, alumni, and others—to satisfy. Women of color have to juggle more than demanding constituencies. We must also juggle our intersectional identities and community responsibilities that others may not have. We have all been taught, “those to whom much is given much is required” (Luke 12:48). On one hand, we embrace some stereotypes, and on another hand we are required to transcend them. We are leaders on our campuses and in our communities, role models to our students, but also to others. We walk on a tightrope of expectations and scrutiny understanding that a false step, a stumble, can be fatal to our careers and to our communities. We, in the words of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, “wear the mask” that disguises our vulnerability and our humanity.

The women who have contributed to this volume are women of courage. They have transcended the racist, classist, hierarchical demands that they both assimilate and acculturate, at least as they share in these pages. They have ← x | xi → dropped their Dunbar mask and embraced their vulnerability to serve those who will follow them. They have shared their triumphs, and also their frustrations. They have stepped out of the shadows of invisibility, broken the silence that surrounds being “other,” and challenged their colleagues to remove the blinders that may have shaped their perceptions and behaviors, however subtle. As I read these essays, I found myself nodding, hollering, and occasionally laughing. They hit home. They are singing the lives that are not always sung, writing lives that are too rarely written, from, as Menah Pratt-Clarke in chapter two writes “beneath the adobe ceilings, the bamboo ceilings, and the plantation roofs.”

While these accomplished high achievers have made history, shattered ceilings, and been stellar role models, they have paid a price for their success. In elbowing their way into a space that was less than welcoming, they have experienced loneliness, isolation, burnout, and marginalization. These are fierce and feisty women, reflective and resistant, who have chosen to walk down a road that Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muys describes as “a yellow brick road,” and as “treacherous.” How can a career path be both the source of the optimism associated with an Oz-ian yellow brick road, and the danger and pessimism associated with treachery? These women’s stories explain the duality, the mask wearing, and the double-consciousness WEB DuBois refers to in The Souls of Black Folks. On one hand, there is the absolute joy of making a difference, especially when it is a difference in the lives of our students. On the other hand, there is the frustration of feeling as if one is banging her head against the brick wall of resistance.

I recall many joyful days as President of Bennett College, but I also remember extremely frustrating ones. I often despaired, wondering if I really made enough of a difference, and why I had to fight so hard, sometimes to do so. On a particularly despondent evening, having come home alone and a bit unaffirmed after three events, a colleague happened to drop by just in time to put a halt to my pity party. She walked me outside my home and pointed to one of the new well-lit buildings that was constructed during my leadership (exceeding all expectations). “This is what you did,” she said. “Don’t ever doubt that you made a difference.” Of course it is not all about the bricks and mortar. It’s about the students who traveled internationally with me, the students who had access to new entrepreneurial studies programs, and the grateful notes I still get from students and parents who remind me that I made a difference in their lives. Still the question remains—why do we have to fight to make a difference?

In chapter six, Menah Pratt-Clarke and Jasmine Parker share this insight from Lee and McKerrow (2005, pp. 1–2): ← xi | xii →

Social justice leaders strive for critique rather than conformity, compassion rather than competition, democracy rather than bureaucracy, polyphony rather than silencing, inclusion rather than exclusion, liberation rather than domination, action for change rather than inaction that preserves inequity.

The women who have contributed to this volume, social justice leaders all, have provided us with an opportunity to think about the real meaning of the term “diversity and inclusion,” to think about the meaning of leadership, and to augment leadership stories with leadership lessons from those who are “other.” Menah Pratt-Clarke’s vision in producing this volume is to be commended. She has engaged in revolutionary scholarship, and we are all in her debt.

Reference

Lee, S. S., & McKerrow, K. (2005, Fall). Advancing social justice: Women’s work. Advancing Women in Leadership Online Journal, 19, 1–2. Retrieved from http://www.advancingwomen.com/awl/

Menah Pratt-Clarke

I want to first thank the series editor, Rochelle Brock, for her commitment to this book. I am grateful for the Black Studies and Critical Thinking series and for the vision and commitment of scholars who have created places for work on race and gender in the academy. I am also grateful for the women of color in the academy who continue to inspire me daily by their deep passion, commitment, and desire to transform spaces that were not meant for them. Women of color scholars who are writing about leadership, higher education, and women are so critical for documenting the journeys of women of color leaders that are often absence from books about higher education leadership. Their work was a very important contribution to this book.

This book would not have been possible if the women who ascended to the top—Paula Allen Meares, Phyllis Wise, Rusty Barceló, Cassandra Manuelito-Kerkvliet, and Waded Cruzado—were not willing to take time to share their journeys. My co-editor, Johanna B. Maes, has been a wonderful partner. I am grateful for her willingness to take a chance to work together to move these stories from silence to the pages of this book. I want to also thank Julianne Malveaux, who wrote the foreword, for her willingness to support this project. This project could not have happened without the other contributors, Jasmine Parker, Melissa Leal, Tanaya Winder, Irma McClaurin, Valerie Lee, Gabriella Gutiérrez y Muhs, and Victoria Chou. Thank you.

I want to thank my parents, Dr. Mildred Pratt and Dr. Theodore Pratt, who instilled in me a deep passion for learning and who despite the racism and discrimination they endured as Black scholars, demonstrated to me the capacity of using education for transformation of lives. My children, Emmanuel and Raebekkah, and my husband, Obadiah, have always been my source of strength and support. My brother, Awadagin, remains a constant inspiration to me. ← xiii | xiv →

My friends, Mercedes, Alfreda, Watechia, Kevin, Marc, Darlene, Patsy, and Gellert, and many others, give me such joy and laughter—laughter that sustains me and provides an incredible source of motivation. Finally, I want to acknowledge my ancestors, those who were enslaved from Africa in America in Texas and Alabama, and those who returned to Africa, to Freetown, Sierra Leone. You are a constant reminder of the power of the human spirit to overcome, to survive, and to thrive. Thank you.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 220

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433140723

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433140730

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433140747

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433131837

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433131820

- DOI

- 10.3726/b10802

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (February)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2017. XVIII, 220 pp.