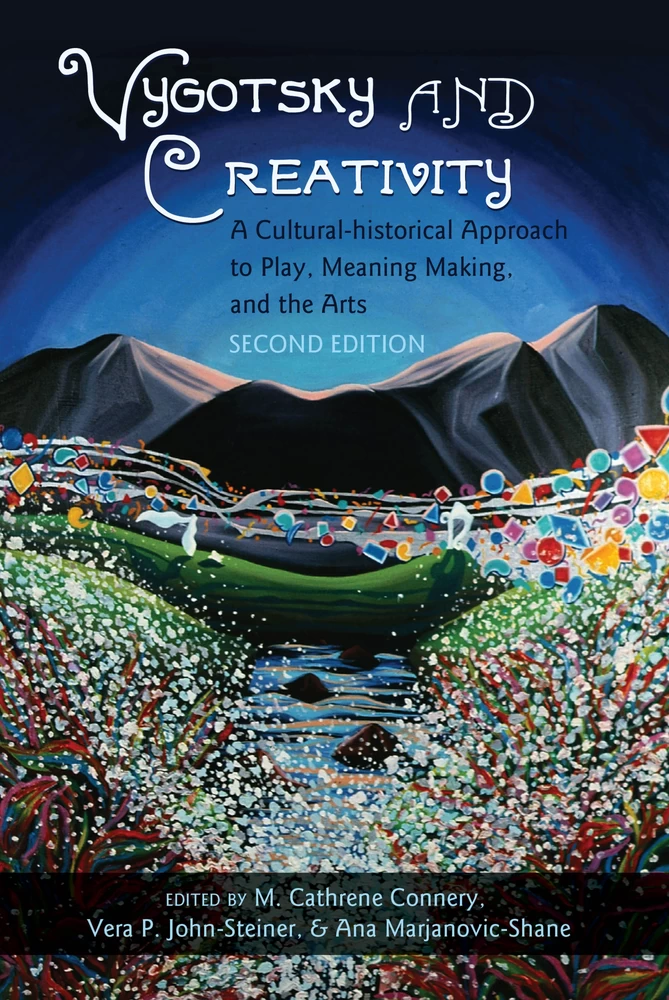

Vygotsky and Creativity

A Cultural-historical Approach to Play, Meaning Making, and the Arts, Second Edition

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures and Table

- Acknowledgments

- Part One: Theoretical Foundations

- 1. Dancing with the Muses: A Cultural-Historical Approach to Play, Meaning Making, and Creativity (Vera John-Steiner / M. Cathrene Connery / Ana Marjanovic-Shane)

- 2. The Historical Significance of Vygotsky’s Psychology of Art (M. Cathrene Connery)

- 3. Without Creating ZPDs There Is No Creativity (Lois Holzman)

- 4. Agentive Creativity in All of Us: An Egalitarian Perspective from a Transformative Activist Stance (Anna Stetsenko)

- Part Two: Domains of Artistic Expression

- 5. Where Is the Body?: Understanding Children’s First Signs and Representations from Their Point of View (Biljana C. Fredriksen)

- 6. Crossing Scripts and Swapping Riffs: Preschoolers Make Musical Meaning (Patricia St. John)

- 7. Constructing the Ensemble: Negotiating Life with(in) Play (Artin Göncü)

- 8. The Social Construction of a Visual Language: On Becoming a Painter (M. Cathrene Connery)

- 9. Dance Dialogues: Creating and Teaching in the Zone of Proximal Development (Barry Oreck / Jessica Nicoll)

- 10. The Inscription of Self in Graphic Texts in School (Peter Smagorinsky)

- 11. Commitment and Creativity: Transforming Experience into Art (Seana Moran)

- Part Three: Connections Between Creative Expression, Learning, and Development

- 12. A Synthetic-Analytic Method for the Study of Perezhivanie: Vygotsky’s Literary Analysis Applied to Playworlds (Beth Ferholt)

- 13. Keeping Ideas and Language in Play: Teaching Drawing, Writing, and Aesthetics in a Secondary Literacy Class (Michelle Zoss)

- 14. From Yes and No to Me and You: A Playful Change in Relationships and Meanings (Ana Marjanovic-Shane)

- 15. New Frontiers for Vygotsky’s Theory of Creativity: Neuropsychological Systems of Cultural Creativity (Larry / Francine Smolucha)

- 16. Creating Developmental Moments: Teaching and Learning as Creative Activities (Carrie Lobman)

- 17. A Cultural-Historical Approach to Creative Education (Ana Marjanovic-Shane / M. Cathrene Connery / Vera John-Steiner)

- Contributors

- Index

- Series Index

Figures

| Figure 8.1. | Momma in Curlers (Courtesy of the artist) |

| Figure 8.2. | Synthesis (Courtesy of the artist) |

| Figure 8.3. | Playground of the Heart (Courtesy of the artist) |

| Figure 8.4. | American Pie (Courtesy of the artist) |

| Figure 9.1. | Finding a Personal Dance (Courtesy of Markus Dennig) |

| Figure 9.2. | Improvisation and Play (Courtesy of Markus Dennig) |

| Figure 10.1. | Peta’s Mask (Courtesy of the artist) |

| Figure 10.2. | Dirk and Rita’s Interpretive Drawing (Courtesy of the artists & their parents) |

| Figure 10.3. | Rick’s Architectural Drawing (Courtesy of the artist & his parents) |

| Figure 12.1. | After Pointing at Michael, Milo (Center) Points at Himself (Courtesy of Fifth Dimension) |

| Figure 12.2. | Milo (at Right) Mirrors the White Witch’s Hands and Arms, Extending His Own Upward (Courtesy of Fifth Dimension) |

| Figure 13.1. | The Word Web Spider (Courtesy of Sherelle Patisaul) |

Table

| Table 15.1. | Eight Synergists Important for Healthy Development and Creativity ← ix | x → |

The succesful creation of any book requires multiple forms of expertise, talent, and commitment. We are deeply grateful to the many individuals who joined our dance to share essential gifts that brought this work into existence. Our profound appreciation is extended to the following people: Greg Goodman, our kind, patient, and wise editor; the talented production crew at Peter Lang; and our extraordinary colleagues and friends, Valerie Clement and Bonita Ferguson. We also wish to acknowledge the creative collaboration we have experienced working together as a source of inspiration, growth, compassion, and development. We are grateful to have had the opportunity to truly engage in the creative process over many years, elaborating our thinking, cheering each other on, providing encouragement, and nurturing confidence and trust.

Sadly, as this new edition was being birthed, our mentor, collaborator, colleague, and dear friend, Dr. Veronka Polgar John-Steiner passed away. Through this book, we extend the torch of her passionate dedication, healing wisdom, and brilliant legacy to a new generation of scholars and learners, having witnessed Vera’s enduring hope to be the greatest form of creativity. ← xi | xii →

Part One: Theoretical Foundations

1. Dancing with the Muses: A Cultural-Historical Approach to Play, Meaning Making, and Creativity

VERA JOHN-STEINER, M. CATHRENE CONNERY AND ANA MARJANOVIC-SHANE

Strings sing at the touch of a violinist’s bow. Light and shadow cast across a stage like rivers of silk, while bodies sway to the heartbeat of a wild drum. Sunflowers burst into bloom on canvas, as clay rises on the wheel into a cylindrical dome. We have long been fascinated with the ability of the arts to transform the material into the seemingly ethereal. As children and adults, we have all been inspired to play, act, and dream on paper, in poetry, or through performance in our personal and professional lives. Across time and space, politics and religion, we are united in our collective need to dance with the muses as both artists and audience members.

So why have the arts been neglected by scholars of human development? Is it a consequence of the rationalistic bias of our educational system? Is it because development in literacy and mathematics is more accessible or open to measurement than growth in dramatic play, music, or drawing? In both the first and second editions of this book, we make the argument that thought, emotion, play, and creativity, as well as the creation of relationships, are an integrated whole. When some aspects of this totality are broken apart, learning and development are diminished.

As editors and authors, we bring to this issue a background in Vygotskian scholarship as well as that of practicing artists and educators. Since the first publication of this text, the ideas of the groundbreaking Russian psychologist, L.S. Vygotsky, have gained increased popularity in their emphasis on the social sources of development and the central role of tools and artifacts in learning. Vygotsky’s theory contrasts sharply with the more dominant approaches of ← 3 | 4 → constructivists (i.e., those of Piaget) who envisioned development as a universally shared process independent of the historical and cultural environment. Vygotsky’s strong emphasis on culture and social interaction is particularly relevant to our contemporary, multicultural society and has been effectively applied to studies of literacy, concept formation, and multilingualism. Ironically, although his first publication was devoted to the arts, cultural-historical scholars dedicated to his thinking have paid little attention to analyses of play, meaning making, and creativity.

As individual scholars, each of us has drawn on Vygotsky’s framework to investigate our own interests in play, meaning making, and creativity. Through these explorations, we encountered colleagues from a diverse array of disciplines who shared our fascination and curiosity and were eager to contribute to this book. Using cultural-historical theory, an approach founded on Vygotsky’s theories and developed further in the former Soviet Union, the United States, and other countries, we collectively sought to articulate a response to these essential processes in the life of the mind. While our informal, formal, political, and creative efforts inspired the first manuscript, this second edition arose from the need to more fully expand our initial thinking. Hence, we are delighted to present a second, reorganized edition with four additional chapters that integrate the scholarship of emerging and revered scholars into the book’s larger circle of thought.

The purpose of this introductory chapter is threefold: First, we seek to introduce the reader to Vygotsky as a teacher, researcher, scholar, and fellow creative spirit. Second, we provide a background of his ideas by summarizing essential concepts from the collection of loosely associated theories that constitute cultural-historical theory, followed by a discussion on play, meaning making, and creativity to present an enriched understanding of the arts. Finally, we introduce the scholarship of the contributors to the text inside the larger text, grateful to our colleagues for the opportunity to offer a more elaborate, complete corpus of writings. We are confident that our readers will appreciate how new chapters on sign development, play, and creativity enhance this second edition.

L. S. Vygotsky: A Life of Creative Activity

L. S. Vygotsky was born in 1896 in Orsha, Russia, a small town, which is now part of Belarus. The young boy grew up in Gomel, as a member of a large, highly educated, Jewish family (Blanck, 1990). By the time he reached adolescence, Vygotsky developed strong intellectual interests in many disciplines, including philosophy and history and shared his mother’s love of poetry. ← 4 | 5 → He finished gymnasium with great distinction and subsequently attended Moscow University where he studied law. He supplemented this course of study with classes at the Shanjavsky People’s University, continuing his interest in history and philosophy. As an adolescent, the young man composed several drafts of an analysis of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which later became the basis of his doctoral dissertation. During these years, he also broadened his knowledge of linguistics and psychology. Vygotsky was influenced by William James and Sigmund Freud and, throughout his life, he conducted a thorough study of European and American psychological theories (Blanck, 1990).

After completing his university studies, Vygotsky returned to Gomel, where he taught in state schools. He also participated in the town’s cultural life. During these years, he mostly published literary reviews and became interested in educational psychology. Vygotsky’s interest in literature and drama established his reputation as a brilliant lecturer. Unfortunately, Gomel suffered the hardships of civil war and attacks made by different armies and local bandits (Rosa & Montero, 1990). Nevertheless, Vygotsky began his first psychological investigations while teaching at Gomel’s Teacher’s College. During this time, Vygotsky’s family was first struck by tuberculosis and his younger brother died of the illness. While taking care of his brother, Vygotsky himself also became ill with TB. After his marriage in 1924 to Roza Smekhova, he left Gomel for Moscow at the invitation of a senior faculty member and psychologist, Alexander Luria. Vygotsky’s collaboration with Luria and Leont’ev would prove to be a highly creative endeavor (Blanck, 1990).

Once in the capital, Vygotsky joined the Institute of Experimental Psychology where “from very early in his professional life he had seen the development of the science of man as his cause, a cause he took extremely seriously and to which he dedicated all of his energy” (van der Veer & Valsiner, 1991). His first publication was The Psychology of Art (Vygotsky, 1925/1971) described by Cathrene Connery in Chapter Two. Vygotsky went on to publish 15 articles a year including lectures, reviews, and forewords to works of foreign authors. His second book was published in English as Educational Psychology (1992). In the late 1920s, his interests expanded to children with atypical development including blind, deaf, and retarded children. Publications on this topic were assembled in Volume 2 of his collected works. Vygotsky’s theoretical analyses were first summarized in “The Historical Meaning of Crisis in Psychology” (1927) which first appeared in English in Volume 3 of his collected works.

Increasingly, Vygotsky became interested in how human activity is mediated by artifacts, a topic that he first developed in “Tool and Symbol in Child Development.” This manuscript forms the first section of the volume Mind in ← 5 | 6 → Society (1978) co-edited by Michael Cole, Vera John-Steiner, Sylvia Scribner, and Ellen Souberman. Throughout his life, Vygotsky relied on a dialectical Marxist approach to the development and investigation of the human sciences. His most widely read work is Thought and Language, first published in English in 1962. In this book, he brings together his cultural-historical ideas with a focus on the interrelationship of thinking and speaking. The impact of this volume has grown substantially over the years and has been published and reedited several times. Vygotsky’s ideas were shaped by his extraordinary scholarship, his deeply original mind, and his ability to work interdependently with colleagues and friends. His legacy might have been lost were it not for Luria’s determined efforts to bring Vygotsky’s work to a world audience after his untimely death from tuberculosis at the age of 38.

Essential Concepts of Cultural-Historical Theory

Vygotsky’s conceptual framework provides a rich, unique, and pragmatic contribution to theories of human psychology. His notions regarding the social sources of development, mediation, perezhivanie, the zone of proximal development (ZPD), and methodology collectively describe the transformative development of individuals and societies. The following discussion highlights the significance of these concepts in order to inform a cultural-historical understanding of play, meaning making, and creativity.

Social Sources of Development

The common theme that runs across Vygotsky’s diverse writings is that of the social origins of psychological processes. Human beings are irrevocably interdependent. As infants, we are dependent on caregivers for survival and learning. In the course of development, young learners rely on the vast pool of transmitted experience shared by family members, teachers and peers. In his oft-quoted “genetic law,” Vygotsky emphasized the primacy of social interaction by proposing that any process in the child’s cultural development appears twice: Functions appear first on the social, then on the psychological plane or first between people, and then within the child as an intrapsychological process.

Imagination, as a psychological function that is located in the core of learning and development, also originates within social interaction and the cultural-historical moment of a child’s development. Vygotsky wrote that “imagination operates not freely, but directed by someone else’s experience, as if according to someone else’s instructions” (Vygotsky, 1930/2004, p. 17). ← 6 | 7 → In this manner, imagination “becomes the means by which a person’s experience is broadened, because he can imagine what he has not seen, can conceptualize something from another person’s narration and description of what he himself has never directly experienced” (Vygotsky, 1930/2004, p. 17).

Vygotsky’s genetic law of development is also observable in the development of speech. He proposed that language functions as a means of communication and cognition. Young children appropriate and make their own the speech that surrounds them. The internalization of dialogic interaction results in the development of language and thought. The semiotic means a child uses during internalization becomes the basis of her inner speech and verbal thinking. The condensed nature of inner speech was described by Vygotsky in his well-known metaphor stating “a thought may be compared to a cloud shedding a shower of words.…Precisely because a thought does not have its automatic counterpart in words, the transition to thought from word leads through meaning” (Vygotsky, 1987, p. 251). Contemporary students of language acquisition emphasize the interactional sources of language learning and language use (Tomasello, 2008). The communicative or interactional use of language, in fact, depends on the imagination of others. In this manner, learning from another can and should become an “experience based on imagination” (Vygotsky, 1930/2004, p. 17) in order for authentic learning to take place. Toward this end, Carrie Lobman illustrates the importance of teachers’ imagination in Chapter Sixteen.

Mediation

The critical role of mediation in Vygotsky’s theory is most fully analyzed by James Wertsch who noted:

In his view, a hallmark of human consciousness is that it is associated with the use of tools, especially “psychological tools” or “signs”. Instead of acting in a direct, unmediated way in the social and physical world, our contact with the world is indirect or mediated by signs….It is because humans internalize forms of mediation provided by particular cultural, historical, and institutional forces that their mental functioning is sociohistorically situated. (Wertsch, 2007, p. 178)

In this quote, Wertsch highlights another important aspect of Vygotsky’s thinking: psychological tools develop within the diverse cultural and historical settings of humankind. One needs only to evoke the computer to realize how profoundly our memory, planning, writing, and editing processes have changed in our reliance on this relatively new technological and cognitive tool. ← 7 | 8 →

Most scholars within the cultural-historical tradition emphasize language as central to thought and pay limited attention to symbolic systems and other semiotic means. While we recognize the critical role of language, we prefer a pluralistic theory that John-Steiner (1995) named “cognitive pluralism.” Some examples of these diverse semiotic means include mathematical symbol systems, maps, artistic sketches, sign language, imagery, and musical notes. These systems of representation are imbedded in social practice in that, “ecology, history, culture and family organization play roles in patterning experience and events in the creation of knowledge” (John-Steiner, 1995, p. 5).

In the sections that follow, the authors describe a variety of meditating tools. In Chapter Six, Patricia St. John documents children’s reliance on musical instruments in her chapter. Peter Smagorinsky writes of students’ construction of masks and their impact on writing activities in Chapter Ten. Cathrene Connery highlights the appropriation of physical and psychological tools in painting as a young adult in Chapter Eight. Reliance on mediating tools is a developmental process which Vygotsky emphasized “is neither simply invented nor passed down from adults; rather it arises from something which is not originally a sign operation and becomes one only after a series of qualitative transformations” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 46, italics in the original).

Perezhivanie

While Vygotsky’s work is strongly cognitively oriented, he also included affective considerations in his theory of human development and consciousness. One of these is perezhivanie, which some have translated as “lived emotional experience.” Social interaction among children and adults is perceived through the lens of previous experience; mediational means are appropriated and represented by individuals in their own characteristic ways. In Chapter Thirteen, Michelle Zoss highlights how teaching and learning are enriched when classrooms provide opportunities for students to express ways of the impact* of their experience. Ana Marjanovic-Shane illustrates how interaction and instruction are enhanced when built on trusting relationships in play in Chapter Fourteen, including vivid and metaphoric descriptions of experience that produce emotional engagement.

The term perezhivanie is an important one in theater director Stanislavsky’s teaching of actors. He asked them to relive previously relevant or profound experiences when preparing to engage with a new role. Vygotsky was influenced by this work and appropriated the concept for his own thinking about emotional experience. It is only recently that his essay, “The Problem of the Environment” in which he developed his understanding of lived ← 8 | 9 → experience, was published in English. Diverse authors in the cultural-historical theoretical community, now familiar with this concept, increasingly refer to perezhivanie as they recognize its significant role in parenting, teaching, and communicating among partners. In Chapter Twelve, Beth Ferholt presents a novel means of studying perezhivanie through the unique use of film.

Emotional aspects of experience are also crucial for imagination. Vygotsky agreed that “all forms of creative imagination include affective elements” (Vygotsky, 1930/2004, p. 19). In his exploration of children’s imagination and creativity, Vygotsky often spoke of the circular path of imagination from lived experiences, through the imagination that combines and recombines elements of these experiences, to the embodiments of imagination in the material form of an artistic product (image, music, dance, story, etc.). According to Vygotsky, for such a circle to be completed, both intellectual and emotional factors are essential (Vygotsky, 1930/2004, p. 21). Toward this end, Barry Oreck and Jessica Nicoll describe how young dancers engage on this path as they develop a personal vocabulary of movement in Chapter Nine.

Zone of Proximal Development

The most widely discussed concept in Vygotsky’s writings is that of the ZPD. Vygotsky wrote “We propose that an essential feature of learning is that it creates the zone of proximal development; that is, learning awakens a variety of internal developmental processes that are able to operate only when the child is interacting with people in his environment and in cooperation with his peers. Once these processes are internalized, they become part of the child’s independent developmental achievement” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 90). The appeal of this notion of assisted performance that precedes a learner’s ability to independently solve tasks has widespread educational implications. Learners differ in how efficiently they use assistance and this difference was of significance to Vygotsky’s argument. To understand the full meaning of the ZPD is to recognize that it is not a recipe for teaching skills. As Lois Holzman emphasizes in Chapter Three, the ZPD is a relational process that embraces the full unity of the social and personal aspects of development in which new functions are realized that are not yet mature.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 342

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433146985

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433147029

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433147036

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433130595

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11605

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (May)

- Keywords

- Children Vygotsky Cultural-historical activity theory Sociocultural Theory Emotion Affect Thought Play Meaning-making Art Psychology Education Creativity Learning Development Catharsis

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XII, 342 pp., 12 b/w ill., 1 table