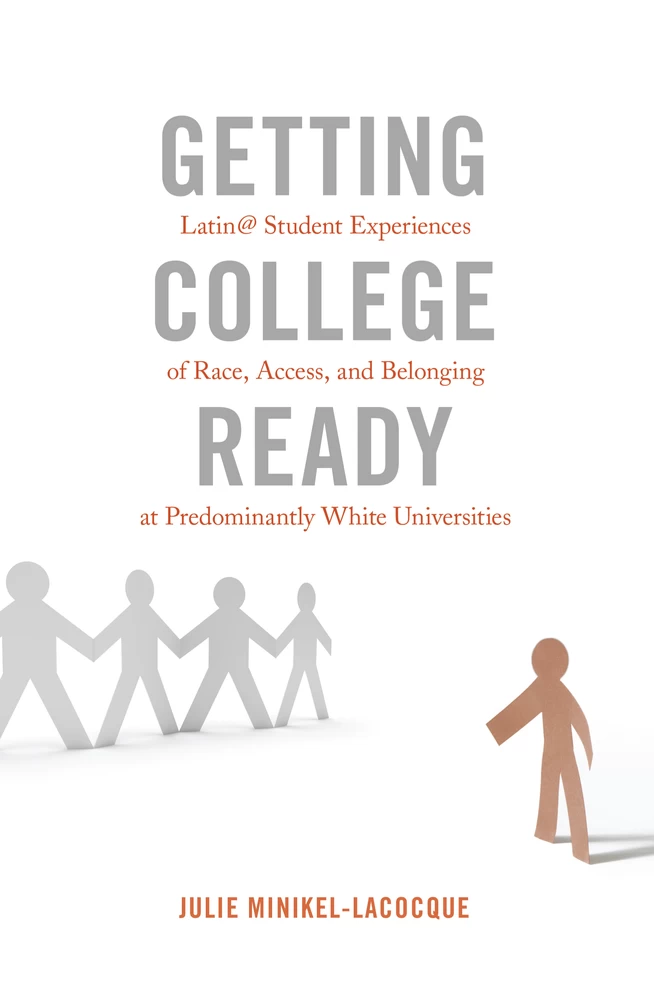

Getting College Ready

Latin@ Student Experiences of Race, Access, and Belonging at Predominantly White Universities

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- The Changing Face of College in the United States: A Reality?

- The College Student Population Today

- The State of Affairs at Flagship Campuses in the United States

- U.S. Latin@s in Higher Education

- The Study

- Framing the Study: Critical Race Theory

- The Role and Subjectivity of the Researcher

- Organization of the Book

- A Glossary of Key Terms Used to Refer to Students

- Latino(s)

- Latino/a(s)

- Latin@

- Underrepresented Students

- How I Use These Terms

- Chapter 1. Student Portraits

- Antonio

- Crystal

- Engracia

- Jasmine

- Moriah

- Mario

- Chapter 2. College Access Programs: Mapping the Terrain

- Introduction

- Conceptual Perspectives

- Critical Race Theory

- Cultural/Social Reproduction Theory

- Student Support Programs

- Private, Nonprofit Programs

- Higher Education-Sponsored Programs

- State- or Federally-Funded Programs

- Community-Based Programs

- Internal High School Support Programs

- Social and Cultural Capital as Tools for Gaining Program Access

- Mario

- Moriah

- Crystal

- Engracia

- Jasmine

- Antonio

- Chapter 3. “To Drop Out or Not to Drop Out?” Student Experiences after Program Acceptance

- It’s Not about the Grades

- Personal Connections and Caring Mentors

- Finances

- Antonio, Crystal, and Engracia: All Set

- Mario: Saved by “A Web of People”

- Moriah: Barely Making Ends Meet

- Jasmine: It’s Not Worth the Money

- Key Program Components

- Explicit, Early Exposure to College

- Caring Mentors and a Built-In Peer Network

- Rethinking Success: Beyond Programs and Grades

- Chapter 4. “Race Shouldn’t’ Matter, but It Does”

- Racial Selves, Identities, and Belonging

- Introduction

- Racial Selves and Racial Ideology

- Student Experiences

- “Very Mexican” in Collegeville: Antonio

- Liminal Spaces: Mario

- Phenotype and Belonging

- Counterspaces and Campus Involvement

- The Case for More Diversity

- Conclusions

- Chapter 5. Racism, College, and the Power of Words:

- Racial Microaggressions Reconsidered

- College Campuses and Racial Microaggressions

- A Taxonomy of Racial Microaggressions

- Critical Race Theory and This Chapter

- Racism at CMU

- Getting Stared at and Feeling Isolated

- Ignored at the Bus Stop and Angry Bus Drivers

- Stereotyping

- Insensitivity and Ignorance

- Online Hatred at CMU and Intentionality: Not So “Micro”

- The Nickname Story: A Contested Microaggression

- Conclusions

- Chapter 6. “You See the Whole Tree, Not Just the Stump”

- Religious Fundamentalism, Capital, and Public Schooling

- U.S. Latin@s and Demographic Shifts

- U.S. Latin@ Families and Schooling

- Fundamentalism, Schooling, and Identities

- In Jasmine’s Words: The Data

- Jasmine and Fundamentalism

- Before CMU: A Wary Relationship with School

- Facing Ambiguity

- Marriage Equality

- Debatable Faith?

- Hypnotists and Hairdos

- Intersections

- Conclusions and Implications

- Chapter 7. “You’re Getting a Little Too Knowledgeable”

- School Kids and Changing Family Relationships

- Family and Critical Race Theory

- The Formation of School Identities

- The Family’s Role in Student Transition to College

- Giving Back to Family and Changing Family Relationships

- Engracia’s Experiences: The Data

- Engracia, School Kid

- “I want to get my dad a Rolex”

- Changing Family Relationships

- Conclusions

- Chapter 8. Is College Ready? Fostering Relationships and a Sense of Belonging

- The Students

- Antonio

- Crystal

- Engracia

- Jasmine

- Mario

- Moriah

- Rethinking Programs

- Early, Sustained Contact with University

- Expanded Understandings of “Success”

- Recognition of Identities Beyond Fixed Categories

- Explicit Emphasis on Racism

- The Call for Border Crossing

- Relationships and a Sense of Belonging

- Epilogue

- Note

- Bibliography

- Index

- About the Author

← xii | xiii →ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost, my deepest gratitude goes to Antonio, Crystal, Engracia, Jasmine, Mario, and Moriah. I also wish to thank the various CMU staff and faculty members who allowed me into their offices and classrooms, agreeing to speak with me in the name of improving college access and success for underrepresented students.

Maggie Hawkins guided me through years of preparation for this project. Through my apprenticeship with her and her caring support, whole worlds were opened up to me. Her insight and critique on various drafts of this project were invaluable. Simone Schweber generously served as my “ideas consultant” during multiple phases of this project. I especially thank her for the hours spent together in her office as she helped me work through the sometimes thorny nature of in-depth, qualitative research. It was through these conversations and her faith in me as a scholar that I learned how to conduct humane, compassionate research.

I wish to thank others who read chapters and offered their keen insight: Paula McAvoy, Derria Byrd, Robin Fox, Gloria Ladson-Billings, Stacey Lee, Ruth López Turley, René Antróp-González, Amato Nocera, Marci Alexander, and Tom Blau. For providing meals and play dates and sharing in my excitement along the way, I thank Dawn Blau and Jean Haughwout. My appreciation ← xiii | xiv → also goes to the friends and family members who listened with a supportive ear as I talked about this research and understood my absence, physical or figurative, due to my absorption in this project.

Heartfelt appreciation goes to my parents, Maria and Jim, for providing unwavering support, reading drafts along the way, and helping with childcare so I could squeeze in those all-important “writing days.” My unending gratitude to Maria, my mother, whose passion for writing sparked my own, and, who, with love, patience, and exceptionally hard work, helped me learn to write so many years ago. Thank you to my sisters, who have always encouraged me, have read and engaged with my work, and have taught me much.

Thank you to Katy Heyning and the College of Education and Professional Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, whose generous support and guidance made this book possible. I also thank my wonderful students at UW-Whitewater for their excitement and curiosity about this book. And I deeply thank the editor of this series, Virginia Stead, for her kind responsiveness and sharp editing.

And finally, and most certainly not least, my profound gratitude goes to my life partner and number one support, David. I could not have done this without his unrelenting encouragement, expert parenting abilities, and sharp intellect that was always at the ready for numerous consultations. My thanks and love go to my children, Benjamin and Adah, for their curiosity, sense of justice, and for their understanding of the time I needed to dedicate to this project. Thank you.

← xiv | 1 →INTRODUCTION

When I left home for college on that August morning in 1991, I was ready. My parents, both college educated, sat quietly in front of me, navigating our trip through the picturesque midwestern landscape sprawled before us. The giddy excitement that pulsed through me was only somewhat tempered by the knowledge that within a matter of hours I would face an emotional goodbye to them. Mostly, I was ready. Ready to take on the next chapter of my life, this time-honored last stage on the road to becoming a full-fledged adult. I was ready to explore, to experiment, to “find myself.” I was confident in the preparation my suburban public education had provided me, and I was ready to take on something more challenging. I never once doubted my parents’ ability to pay my tuition, and I planned on looking for a part-time campus job in a few weeks. I was ready to leave my friends and family, all of whom were either college graduates or current students themselves. Significantly, I am also White. I embarked on this adventure knowing that my peers in college would be from similar backgrounds, not only educationally and socioeconomically but also racially. I was not afraid of standing out or being mistreated because of how I looked.

My small liberal arts college, importantly, was also ready for me. It boasted a long history of educating mostly middle- and upper-class Whites, and it was ← 1 | 2 → one of the few colleges of its age that opened its doors to men and women since its inception. It was known for its academic rigor, its enriching campus-sponsored activities and programs, and its robust social life. It was, in all ways, ready for a well-educated, middle-class, White feminist student who was prepared to take on the many challenges it would offer.

This book, however, is not about the luxury of such a seamless transition to college. This book is about the experiences of six Latin@ college students, most of whom are the first in their families to attend college, as they transition to a prestigious, predominantly White state flagship university in the Midwest, which I call Central Midwestern University (CMU).1 Over the course of a year, I got to know these young men and women as they shared their lives with me. In what follows, I share their voices and experiences as I understood them as well as the lessons gleaned from my time with them—lessons that demand we examine the ways in which we conceive of “college readiness.”

The Changing Face of College in the United States: A Reality?

At its inception in the late 1780s, U.S. higher education was solely for the elite white male (for a thorough history of higher education in the United States, see Thelin, 2004). Roughly 50 years later, women’s colleges were founded, followed by various coeducational institutions. Federal policies such as the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862 and the GI Bill of 1944 were aimed, in part, at increasing access to higher education, thus effectively diversifying campuses. This series of changes on U.S. campuses has continued today, less as a result of federal policies directed at higher education and more due to social change. Today, greater attention is paid, for example, on many campuses to accessibility for those students with physical disabilities; most campuses have recognized the need to create a safe atmosphere for LGBTQ students; various types of support exist for first-generation students, students from a low SES, and for Students of Color; and, finally, campuses across the United States are publicly engaged in efforts to recruit students and faculty from underrepresented groups.

Indeed, efforts to make campuses more diverse are made highly visible; most universities showcase their commitment to diversity on their website’s homepage and in recruiting materials. These public displays of inclusion can ← 2 | 3 → mask an unfavorable reality, however. One prominent public university’s website, for example, recently displayed a photograph of fans at a sporting event. It was discovered, however, that the university used computer software to alter a photograph of a group of White fans at the sporting event to include images of students of color, thus giving the appearance of a more diverse crowd. Indeed, a closer look reveals a disconnect between rhetoric and reality; despite these advertised efforts, most public four-year universities remain predominantly White.

The College Student Population Today

Attaining a college education is often equated with “moving up in the world,” and with good reason. College graduates not only have access to more desirable jobs and enjoy the higher status associated with a college degree, but they also have a significantly higher earning potential than their non-college-educated peers (Barrow & Rouse, 2005). A post-secondary education, however, is not equally accessible to all sectors of the U.S. population, which is becoming increasingly diverse: Between 2000 and 2010, 63% of the growth in the population aged 18 to 24 years was People of Color (U.S. Census Bureau, as reported in Orfield, Marin, & Horn, 2005, p. 61). Additionally, nearly half of U.S. public high school graduates came from lower-income families in 2006 (Orfield et al., 2009, p. 61). Thus, more than ever, the pool of potential college students is highly diverse both racially and socioeconomically.

Unfortunately, the reality of an increasingly diverse population has decidedly not translated into our college campuses becoming more diverse. A brief stroll through a sampling of campuses across the U.S. reveals that far too many of our institutions of higher education—even those that are public and therefore ostensibly accessible to a wider portion of the population—are predominantly White. Indeed, differences in college-going and -completion rates along socioeconomic and racial divides are staggeringly large: In 2000, the gap in college-going rates between low- and high-income traditionally aged college students was nearly 30%, and today these discrepancies continue to grow (College Board, 2002, as reported in Orfield et al., 2005, p. 62). With regard to race, in 2010, 30.3% of Whites aged 25 and over had a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 19.8% of African-Americans and only 13.9% of Latinos (Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012, p. 151). In addition, the first-generation college students are “relatively rare” at the ← 3 | 4 → nation’s selective institutions of higher education (Espenshade & Radford, 2009, p. 23).

The State of Affairs at Flagship Campuses in the United States

Flagship universities in the United States are commonly conceived of as the largest, most prominent public research-focused university in a given state, designed to offer an affordable, top-notch education to its citizens. As Tobin (2009) explains, American flagship universities “were created to meet the social and economic needs of the states that chartered them, to serve as a great equalizer and preserver of an open, upwardly mobile society…” (p. 240). Most flagship universities are also land-grant institutions, a category brought about by the Morrill Land Grant Act of 1862. The Morrill Act created a partnership between the federal and state governments and “granted” states land on which the state was mandated to provide accessible, affordable higher education focused on “useful arts” to its citizens. However, the perceived legacy of the Morrill Act is contested, and some scholars argue that the effects of the act “have been misunderstood or exaggerated” and point out that many “land-grant” institutions already existed before the Morrill Act, and, what’s more, were already engaged in efforts to offer “practical” fields of study (Thelin, 2004, p. 76–77).

Despite the commonly understood mission of flagships to be the “people’s universities,” these institutions also face criticism for their lack of diversity. In fact, the lack of diversity seems to be more pronounced at the country’s flagship universities, and the problem is worsening. At flagships, the percentage of students from families in the top income quartile has been steadily rising since 1982; and, at the same time, the percentage of students from low-income families at flagships has been declining (Tobin, 2009). Rising tuition costs and increased selectivity at many flagships over the last few decades have combined to decrease access to these institutions (Bowen, Chingos, & McPherson, 2009). In addition, at the majority of flagships, the percentage of students with parents who have college degrees is increasing, as is the percentage of students with parents holding graduate degrees (Tobin, 2009). What’s more, although both the number and proportion of Pell Grant recipients has risen overall, the percentage of these students at flagship universities has declined (Tobin, 2009). Bowen and colleagues (2009) put this state of affairs in plain terms: “…flagships are far from ‘representative’; the students at these prestigious universities are, by any measure, a special group” (p. 15).

← 4 | 5 → U.S. Latin@s in Higher Education

Nested within the larger context of the widening achievement gap in the U.S. with regard to post secondary education, as well as the lack of diversity on our campuses, is the condition of college access and persistence for U.S. Latin@s. Indeed, the word “crisis” was recently used to describe the educational context for U.S. Latin@s, who are at once the least educated and the fastest-growing group within the United States (Gándara & Contreras, 2009). Specifically, in 2006, Latin@s made up 19% of the school-age population in the United States; in 2025, one in four or 25% of K-12 students in the country will be Latin@ (Gándara & Contreras, 2009, p. 304–05). In terms of college completion, Latin@s are lagging behind other racial groups, as seen above. And, in 2005, when the students in the study presented here finished their junior year in high school, only 50% of U.S. Latin@ high school students graduated. Additionally, compared to 73% of White high school graduates, 54% of Latin@ graduates went directly to college; the majority of this 54%, however, attended two-year institutions. Significantly, a mere seven percent of bachelor’s degrees were given to Latin@s (U.S. Department of Education, 2007 & 2006.). What’s more, although there has been “substantial growth” in postsecondary degree completion for other groups, Latin@ degree completion has “remained stagnant” (Gándara & Contreras, 2009, p. 24).

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 201

- Year

- 2015

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453915387

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454193630

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454193623

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433127649

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433127656

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1538-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (December)

- Keywords

- minorities underrepresentation social transition

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2015. XIV, 201 pp.