Africa’s Last Romantic

The Films, Books and Expeditions of John L. Brom

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

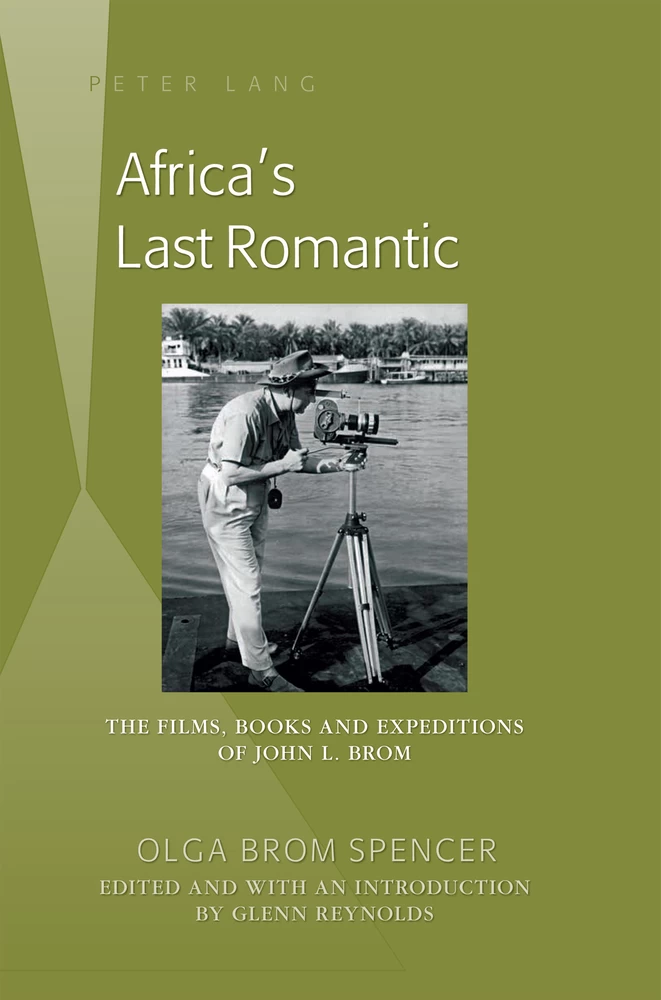

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Narrator’s Acknowledgment

- Editor’s Acknowledgment

- Table of Contents

- Introduction: Africa’s Last Romantic, by Glenn Reynolds

- The Beckoning Land

- European Expeditions to the Nile, the Niger and Beyond

- Images of Africa

- The Pitiless Jungle

- “Jambo”

- Dr. Livingstone, I Presume?

- The Measure of a Man

- Part One: Africa Calling

- Chapter 1: John L. Brom: The Story Begins

- Part Two: 1949-1950—The Cameroun Expedition

- Chapter 2: Launching the First African Expedition

- Chapter 3: Royal Foumban and Unexpected Dangers

- Chapter 4: Civilization is Just a Thin Layer on Indomitable Nature

- Part Three: 1953—20,000 Miles through the African Jungle

- Chapter 5: Multi-dimensional Aspects of Documentary Production

- Chapter 6: Obstacles and Memorable Moments

- Chapter 7: The Wild Kingdom

- Chapter 8: Do you want my wife?

- Chapter 9: The Dark Hours

- Chapter 10: Finishing 20,000 Miles through Africa

- Part Four: 1953-1954—Mau Mau Expedition

- Chapter 11: Dangerous Journey

- Part Five: 1955—On the Footsteps of Stanley

- Chapter 12: Stanley’s Great Journey

- Chapter 13: Explorer’s Multi-tasking

- Chapter 14: West of Bagamoyo

- Chapter 15: Searching for the Nile

- Chapter 16: In the Footsteps of Stanley

- Chapter 17: From Nyangue to Kisangany

- Chapter 18: ‘Icoutou ya Congo’ (‘Name of the River is Congo’)

- Part Six: 1960-1966—The Drumbeats of Independence

- Chapter 19: The New African Elite

- Chapter 20: The Last Voyage to Africa

- About the Authors

- Biographical sketch of Dr. Olga Brom Spencer

- Selected Publications of Olga Brom Spencer

- Biographical sketch of Dr. Glenn Reyolds

- Selected Publications of Glenn Reynolds

| 9 →

Introduction: Africa’s Last Romantic

The Beckoning Land

The ‘golden’ era of European filmmaking in colonial Africa extended from about 1910 to 1960, as a result of increasing interest in the industrialized West in exotic images from distant countries. Following World War Two, Equatorial Africa in particular was a site targeted by filmmakers from all over the world to compete for something new and sensational. There was one European explorer, author and cineaste of the continent who remained fascinated by the fast-disappearing Africa of old, and who worked tirelessly to catalogue its many unique cultures undergoing rapid transition. John L. Brom, heralded for numerous treks through some of the most remote areas of the continent between 1949 and 1962, was in many ways a man born a century too late. Having read in his youth the thick tomes of earlier African exploration, he perhaps would have been more comfortable accompanying one of the many European explorers who traversed the beckoning land of Africa in the second half of the nineteenth century. Yet even in his own time, Brom emerged along with Armand Denis and Lewis Cotlow as one the most prolific postwar chroniclers of the ‘Africa of old’ as the continent veered fitfully toward independence.1 A resourceful man of remarkable wit and tenacity, Brom produced a steady stream of documentary films, books, and television specials on the unique cultural attributes of tribal Africa which were translated into numerous languages and went into wide circulation around the globe.

Brom had begun his film career under trying circumstances during the interwar period. In 1937 he purchased a struggling Czech film production company, renaming it Brom-Film, which released an impressive 10 films between 1935 and 1945. Brom’s burgeoning career as producer and director, however, was soon put in jeopardy with the outbreak of war. As the conflict ← 9 | 10 → worsened, the homefront was increasingly destabilized and Brom-Film was unable to sustain its earlier brisk production schedule. Brom, in fact, had already seen dark clouds developing in Germany, for after gaining power in 1933 Hitler had quickly established the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under the leadership of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels. The result was a veritable breakdown of the industry, as many German filmmakers were arrested or fled the country, and international boycotts cut painfully into profit margins. Filmmakers like Brom in neighboring countries would soon suffer similar misfortunes as the Nazis expanded their sphere of influence throughout much of Europe.

During the war, Brom and other filmmakers found themselves targeted by the Nazis. Yet despite this frightening turn of events, he continued to develop and expand his ideas as a producer. Ironically, it was during this period, when most Europeans were absorbed with the ugly realities of total war that Brom’s long-standing interest in the Black Continent actually blossomed into preparations for launching a film expedition to Africa. Unfortunately, the sudden nationalization of Brom-Film by the Communists after the war ended in 1945 caused yet more delays as he was forced to flee to Paris. But soon, breathing easier in newer climes and with the conflict now concluded, he reinvented himself as a ‘French’ film director, beginning with his postwar transition from Ladislav John Brom, to ‘John L. Brom.’ Between 1949 and 1962, with Paris as his primary base of operations, Brom traveled extensively throughout Africa— with a focus on equatorial regions—producing a steady stream of documentary material detailing the incredible diversity of African life.

European Expeditions to the Nile, the Niger and Beyond

From dictators to dreamers, European interest in Africa has a long and fascinating pedigree. In fact, no continent has been more defined by century upon century of European exploration and discovery, dating back well into antiquity at least to the time of Herodotus. Although scholars dispute the exact itinerary of his explorations, Herodotus, often referred to as the ‘father of history’ for meticulously chronicling his extended foreign adventures in his Historia,2 certainly visited Cyrene and Egypt on the North African coast sometime around 450 BC. These journeys were followed up the next century by Alexander the Great’s ‘liberation’ of Egypt from Persian control in 332 BC, where he was subsequently given the title ‘Master of the Universe.’3 ← 10 | 11 →

One of the ‘great unknowns’ in African exploration, even in days of old, was the exact source of the Nile River. Although Herodotus had compiled a few theories derived from various sources, verifiable knowledge remained elusive. If Pliny the Elder is to be believed, sometime around the burning of Rome in 64 AD Emperor Nero sponsored a Nile expedition with the intent of determining its origin, although the vessels were eventually stymied by the swampy ‘Sudd’ of the White Nile when the maritime expedition reached the South Sudan.

The Middle Ages ushered in a new era of fascination with Africa. In the 14th century the myth of Prester John, a Christian many believed to reside in Africa somewhere ‘beyond the land of the Muslims,’ was fully promulgated by Sir John Mandeville who described in surprising detail the fabulous palace of this noble ruler, the jurisdictions under his control, and the material wealth of his empire.4 Yet Prester John always remained just out of reach, and indeed today there is no firm consensus as to whether the historical ‘Priest John,’ if there ever was one, actually resided in Ethiopia or India. In any event, on the other side of the continent by the 1420s, Prince Henry of Portugal had begun sending out exploratory expeditions along the bulge of Africa in search of the source of the precious goods traveling along ancient trans-Saharan trade routes. It took years for Henry’s dreams to bear fruit, but in the process the Portuguese availed themselves of another precious resource on Africa’s west coast—slaves—a devastating phenomenon that ushered in several hundred years of European slave trading on the continent.5

Interest in African exploration was stimulated yet again in the late 18th century, with the 1788 formation of the African Association (Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa) in London. This British club set its sights on discovering the origins of West Africa’s mighty Niger River, as well as locating the fabled metropolis of Timbuktu (the ‘City of Gold’) which had received attention for centuries by Arab explorers like the Moroccan Ibn Battuta (who himself mistook the Niger River for the Nile in 1353), but which had never been visited by a European. The African Association had mixed results: while Scottish explorer Mungo Park famously laid claim in 1795 to being the first European to travel the interior of Africa as far as the Niger River and emerge alive to record his exploits,6 explorer Daniel Houghton was ← 11 | 12 → robbed and killed in the Saharan desert in 1791, while Friedrich Hornemann, dressed as a Muslim traveling with a caravan from Cairo in 1800, simply disappeared.

Not to be outdone by the British, Napoleon Bonaparte set his sights on Egypt at the twilight of the 18th century, sending in a large French invasion force that overthrew the Mamluks at the Battle of the Pyramids in 1798.7 Although the invasion was a classic military operation, Napoleon pointedly included 160 scholars, savants and artists on the expedition to acquire more knowledge about the long, noble history of the Egyptians, and to lay the cultural groundwork for tying the region more closely to its French colonizers.8

Clearly then, by the time famed explorer Richard Burton described his explorations to a rapt audience at the Royal Geographical Society in 1859, lecturing on “The Lake Regions of Central Equatorial Africa, with Notices of the Lunar Mountains and the Sources of the White Nile,” he could boast of a long history of African exploration behind him.9 And yet Burton was also at the forefront of yet another wave of intense exploration that spanned the second half of the nineteenth century, culminating in the ‘Scramble for Africa’ in which European powers raced to colonize most of the large land mass to their south that straddled the equator.

Images of Africa

Details

- Pages

- 160

- Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453912911

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454197027

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454197010

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433124792

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1291-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (March)

- Keywords

- drama cinema African history

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 160 pp., num. ill.