Irish Education and Catholic Emancipation, 1791–1831

The Campaigns of Bishop Doyle and Daniel O’Connell

Summary

How did Daniel O’Connell use this situation to create a successful mass movement, broadening the emancipation campaign to include the issue of education? How did the area of educational provision become a sectarian battleground, and what part did Bishop James Doyle play in forcing a reluctant government to become involved in setting up a state-run education system, a highly unusual step at the time? Does his vision have a message for us now, when school patronage is such a contested issue in Ireland? This book provides an intriguing new perspective on a critical period in Irish history.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Penal Laws

- Restrictions

- Gradual Change

- Edmund Burke

- The Volunteers

- Further Concessions

- Maynooth College

- Daniel O’Connell

- Irish Education

- Some Critics

- Richard Lovell Edgeworth

- The Act of Union (1800)

- Notes

- Chapter 2: False Dawns

- The New Century

- Political Instability

- Lord Liverpool

- Internal Divisions

- Robert Peel

- Educational Inquiries

- The Kildare Place Society

- Bishop James Doyle

- A Pastoral Letter

- Notes

- Chapter 3: A Strategic Decision

- Peel as Home Secretary

- The ‘Second Reformation’

- The Catholic ‘Rent’

- The Clergy and Politics

- Coercion

- Notes

- Chapter 4: Straws in the Wind

- An Education Commission

- A Detailed Assessment

- The First Report

- Parliamentary Investigations

- Misplaced Optimism

- The Dominant Issue

- Wellington’s Memorandum

- O’Connell’s Darkest Hour

- Notes

- Chapter 5: An ‘Irresistible Necessity’

- Doyle on Emancipation

- Election Year, 1826

- Thomas Wyse

- A Turning Point

- Official Reaction

- A Strengthened Campaign

- A Model School

- Wellington

- The Clare By-Election

- Developing a Response

- Disharmony

- A Belated Concession

- Notes

- Chapter 6: Progress

- A Quick Report

- A Vision for Education

- Exploring Options

- A New Government

- Reform in Practice

- O’Connell and the Government

- Changing Tack

- Reforming the Franchise

- Summer, 1831

- Increasing the Pressure

- The Stanley Letter

- Notes

- Chapter 7: In Retrospect

- An Unusual Development

- A Partnership?

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Books, Book Chapters, Pamphlets and Journals

- Private Papers

- Parliamentary Debates

- Newspapers and Periodicals

- Official Publications

- Index

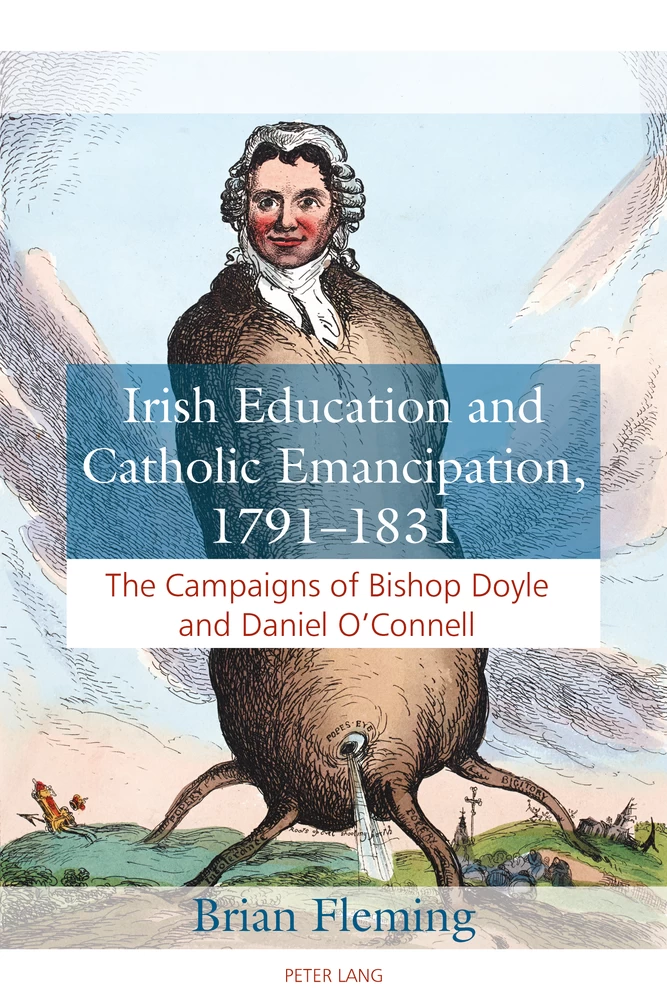

Cover image: ‘The Great Agi-tater’ [sic]. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

The most pointed and satirical political commentary in the early nineteenth century was provided by cartoonists. While they sought to exercise influence on the great issues of the day, they also reflected contemporary thinking. In the case of Ireland, they invariably portrayed a negative picture. No instance has been unearthed that featured Bishop Doyle but O’Connell, identified by his barrister’s robes, was a regular target. In this case his head is on top of a large potato. It has four roots of evil shooting forth: Popery (two), Intolerance and Bigitory [sic]. Two roots are re-emerging from the ground in barbed form. On the left hand side, Popery is uprooting the monarchy. The Established Church is being toppled by Bigitory, on the right, and this is being celebrated by figures in the vicinity. The Pope’s eye is focused on property described as Church of England lands and Protestant ground. The Pope in the background, holding a cross, is addressing a flock in support of O’Connell. Agi-tater is a reference to the dependence of Irish people on the potato. Similarly, the spelling of Bigitory is an allusion to the views of Tory politicians.

Figure 1: ‘Protestant Descendency’ [sic]. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Members of the local Protestant ascendancy are gathered at their church. The rector is holding a petition to Parliament and recommending that approach as the best way forward. They are unaware of impending threats. Below the church, in the cave of the Catholic ascendancy, there is a cask of gunpowder. The sly friar is walking away laying a trail of powder behind him. He is carrying a lighted candle with which he intends to ignite the powder and cause an explosion in order to destroy the church’s foundations. Meanwhile a ← vii | viii → group are attempting the pull down the church spire. At the front, O’Connell exclaims, ‘by St. Patrick I’ve got the rope over at last’. Behind him with his top hat aloft is Sir Francis Burdett, exclaiming, ‘down with it never mind the people’. Next to him is a broom-girl, an allusion to Henry Brougham. At the end of the rope is Wellington and Peel beside him, both recent adherents to the cause of Catholic emancipation. Peel’s waistcoat has been badly stained by the rope, a reference to his complete volte-face on the issue. A group of supporters stand beside them. Above, on the right hand side, is Lord Eldon ploughing a different furrow. A trenchant opponent of any concession, he is warning the Protestant congregation of impending danger from the falling spire: ‘look to your selves’. On the left, in the background a Papal procession is approaching St Paul’s Cathedral, London, in triumph. The monument and fire in the top right-hand corner are a reference to another cartoon in which similar sentiments were expressed.

Figure 2: ‘A 40sh Freeholders only Expedient for the Salvation of Boby [sic] and Soul’. Image © the Trustees of the British Museum.

The freeholder stands between the priest and the landlord, both tugging at his collar. Priests were often represented, as in this case, as well-fed and with a red nose, indicating an over-indulgence in alcohol. He is holding a picture of the devil, smoking a pipe, and a man sitting in a burning bowl and saying ‘Vote for your Priest or see this picture of your soul in the next world’. The landlord says ‘Vote for your Landlord or see the real consequences in this world’. An eviction is taking place in the background and the vacant properties are labelled ‘Wanted Protestant tenants for these Cabins’. The freeholder responds, ‘Sure I’m bother’d hadent I better be after voten for both your honors id would make the thing asier aney how’.

Figure 3: ‘O’Connell at the Bar of the H. of Commons’. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

An engraving of the scene in the Commons when O’Connell declined to swear the anti-Catholic oath, 18 May 1829.

I have received significant assistance in producing this book. Those who work in the National Library, the James Joyce Library at University College Dublin, Seamus Haughey in the Oireachtas Library, Siobhán McCrystal and Linda Donnelly in the local library services (SDCC and Fingal) have all been extremely helpful. The same applies to people looking after archives, including Noelle Dowling (Dublin Diocesan Archives) and Bernie Deasy (Delaney Archives), those who work in the National Archives of Ireland, the UK National Archives, the Public Records Service of Northern Ireland, the Church of Ireland College of Education, Durham University, the British Library and the British Museum. As always, my daughters Ciara and Aoife resolved all difficulties which arose as a result of my lack of IT skills with great patience and understanding.

In the early years of the eighteenth century, the British government introduced various pieces of legislation which placed restrictions on members of the Catholic faith and Protestant dissenters. The intention was to remove them from positions of financial, political and social power. In the longer term, the objective, in the case of Ireland, was to establish Protestantism as the main denomination. The education system was viewed as a key part of that strategy and state support was provided to evangelical societies to establish schools. For various reasons, elements of the coercive legislation were removed over the decades whilst, at the same time, efforts to proselytize gained momentum. By the end of the century the sole remaining disability related to membership of Parliament and a small number of senior administrative positions. Problems in the education system had been acknowledged in official and other reports but no action was taken.

The passing of the Act of Union (1800) prompted some optimism that improvements might follow but this proved to be misplaced. The campaign for Catholic emancipation, that is, the removal of the remaining disabilities, gained some momentum at various stages in the first two decades of the new century. However, divisions on the Irish side and opposition from powerful figures in the British establishment ensured no progress was made. The ‘Catholic question’ began to dominate British politics. Meanwhile, the need for educational reform was again recognized in an official report but resistance from the Protestant ascendancy in Ireland succeeded in maintaining the status quo. The emergence of Daniel O’Connell in that period and the choice of James Doyle as Bishop of Kildare and Leighlin in 1819 were destined to be significant in the years that followed.

The 1820s was a particularly turbulent time in Anglo–Irish relations. The issues of Catholic emancipation and educational provision were hotly debated. Securing an entitlement to membership of the House of Commons, while important symbolically to the Catholic population in Ireland, was not an issue that was likely to benefit many of them directly. ← 1 | 2 → The creation of an acceptable system of elementary education, on the other hand, was of vital importance to many. By this time, educational policy had become something of a sectarian battleground. O’Connell made an important strategic decision in early 1823 to broaden the campaign for emancipation to include education and a range of other issues. He and his colleagues succeeded in creating a mass movement which proved successful, despite some initial difficulties. Broadening the agenda to include education had the effect of drawing the bishops and the clergy into active involvement in the movement. Most prominent among these was Bishop Doyle. Important electoral successes followed in 1826 and most significantly in 1828 when O’Connell was elected in Clare. Progress during this period was certainly not seamless. At various stages there were setbacks in the face of powerful and trenchant opposition. Eventually, reluctant governments in London were forced to concede emancipation in 1829 and significant educational reform two years later. By a strange coincidence, the place of religion in our education system is now, once again, a hotly contested area. Many would suggest that the current generation of policymakers could learn from the solution arrived at almost 200 years ago.

A wide range of sources have been consulted in preparing this account of these developments. These include archives, private papers, books, official reports and daily newspapers. In addition, I have consulted the work of three diarists. Through family connections, Charles Greville (1794–1865) secured a position as clerk to the Privy Council. This afforded him an income and plenty of spare time to indulge his love of horse racing. More importantly, it brought him into close contact with the leading politicians of the day, together with royalty and senior establishment figures. Unmarried, he tended to spend a lot of his time staying in the great country houses of the period. Throughout his life, he kept comprehensive diaries, which included keen and well-informed observations on the issues and personalities of the era. Although he was from a Tory background, his observations tended to be objective in nature. The publication of his diaries after his death was described as a social outrage by Disraeli, and Queen Victoria was said to be horrified and indignant. Another diarist was Thomas Creevey (1786–1836) who served as a Whig MP for various spells between 1802 and 1832. In 1812 he married a wealthy widow, Eleanor Ord, who had five children. For some ← 2 | 3 → years from 1814 onwards, they lived in Brussels, where he became friendly with the Duke of Wellington. His wife died some years later and he returned to live in England. His stepchildren inherited their mother’s wealth and lived in the country whereas Creevey spent his time in London. His friendship with, and admiration for, Wellington, together with his ready access to all the leading Whigs, meant that he was reasonably well-informed. He was an acute observer of people and events and his views on the political developments in London were outlined in a long series of detailed letters to his favourite stepdaughter, Elizabeth. The third diary accessed also relates to the Duke of Wellington. His marriage was not a happy one and his wife Kitty usually stayed at their country home in Hampshire, while he resided in London. Charles Arbuthnot, a Member of Parliament, and Arbuthnot’s wife Harriet, were the duke’s closest friends in the city. They mixed in the highest political and social circles of the period. A well-deserved reputation for discretion, keen political understanding and wise counsel meant that Harriet Arbuthnot had regular detailed conversations with many of the leading politicians of the day. In her opinion, Wellington was superior to his contemporaries and this is obvious from her journal, so she is not an unbiased observer. Her diary is, however, a valuable source of information on his thinking. She regularly disagreed with him on issues and there is no doubt that he greatly valued her advice.

Details

- Pages

- X, 236

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787076594

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787076600

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787076617

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781787073104

- DOI

- 10.3726/b10723

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (July)

- Keywords

- History of Irish education Anglo-Irish politics in the eighteenth century sectarian conflict

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2017. X, 236 pp., 2 coloured ill., 1 b/w ill.