The American President in Film and Television

Myth, Politics and Representation

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

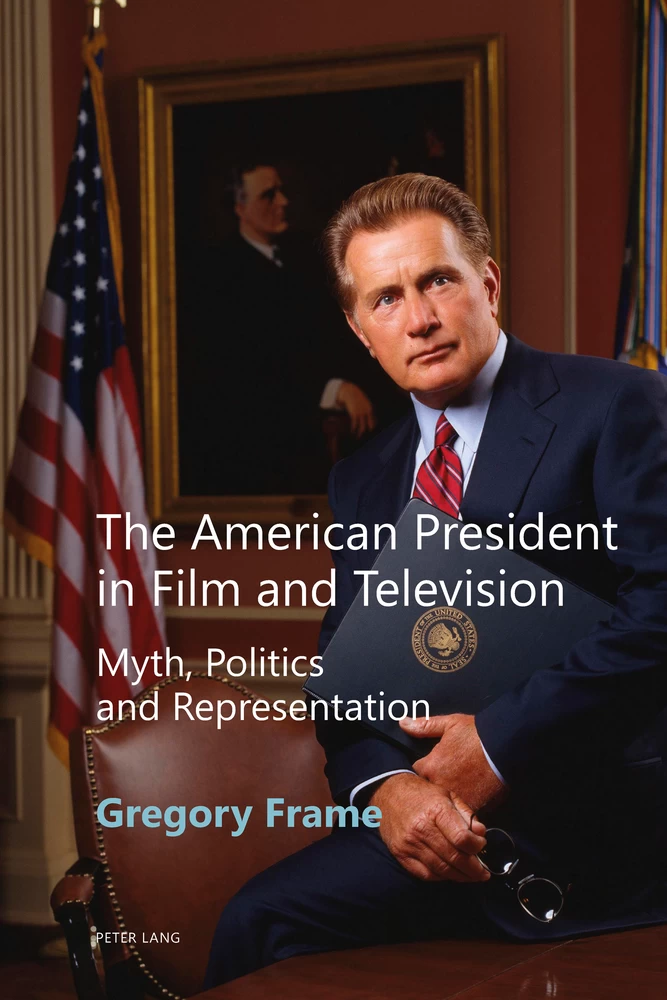

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- About the author

- About the book

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1. Introduction: The American President in History and Criticism

- Chapter 2. The Symbolic Presidency: Washington and Hollywood, 1932–1989

- Chapter 3. The Post-Cold War Presidency in Hollywood Cinema

- Chapter 4. The West Wing: Continuity and Change from Clinton to Bush

- Chapter 5. Predicting Obama? Hollywood’s Black Presidency and the Creation of a Stereotype

- Chapter 6. ‘Having it Allen’: Motherhood, Family and the Female Presidency in Commander in Chief

- Conclusion. Old Constructs in a New Era: The White House Invasion Narrative and the Return of Abraham Lincoln

- Bibliography

- Index

5.2 President Wilson (Danny Glover) passes the baton to Dr Adrian Helmsley (Chiwetel Ejiofor) in 2012 (dir. Roland Emmerich, Columbia Pictures, USA, 2009) ← ix | x →

Many people were shocked and dismayed by Donald Trump’s victory in November 2016. I was one of them. While this book argued claims that the United States had entered a ‘post-racial’ era following President Obama’s victories in 2008 and 2012 were premature given the rise of populist, right-wing forces against his administration, it did not seem even when this book was originally published in 2014 that there was any chance Trump could win the Republican nomination, let alone the election itself. As was noted on Election Night 2016 by author and political commentator Van Jones, Trump’s win could be construed as a racist ‘whitelash’ against the demographic changes in the United States and the country’s first black president.1

However, in many respects the election victory of a reality television star running on a populist platform reinforced the argument of this book that, however seemingly trivial films and television programmes featuring fictional presidents in prominent roles appear to be, they play a vital and significant role in articulating what characteristics people look for in a commander in chief: like many of his fictional counterparts, Trump ran for president as a crusader from outside politics, claiming he wanted to clean up a corrupt system and return power to the people. He fulfilled the desire for a return (if, indeed, such a figure has ever existed) of the authentic politician: not afraid to speak his mind, willing to abandon his predetermined talking points and depart from the teleprompter, and refusing to apply the varnish of a focus group or listen to media polls.2 Unblemished ← xi | xii → by association with the crooked, dishonest politicians that have engineered the system to work only for them and their rich friends, the populist hero rides into town to ‘drain the swamp’. Sound familiar? Think Jefferson Smith (Jimmy Stewart) in Mr Smith Goes to Washington (Frank Capra, 1939), Dave Kovic (Kevin Klein) in Dave (Ivan Reitman, 1993), or Tom Dobbs in Man of the Year (Barry Levinson, 2006). Having said this, a crucial aspect of my argument was that the function of such representations is primarily cathartic. However disenchanted people are with the political system, they will resist the temptation to vote for a figure like this because: firstly, they recognise that reality is much more complicated and the solutions being offered are bunkum; secondly, their yearning for this hero has been reasonably sated by fiction. Donald Trump’s victory flipped this equation on its head. He is, to some degree, a fictional character blundering around in the ‘real world’ of American politics.

So, to a large extent, I should not have been so surprised by Trump’s victory. As I argued of Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter at the conclusion of this book, ‘there remains the desire for a presidential strongman in a period in which the dominant attitude towards politicians and presidents appears to be one of cynicism and disdain, and that such a representation performs a psychological function, simplifying complex issues [and] providing comforting explanations’. To some extent, we can be thankful that Trump believed this fiction, perpetuated by many of the portrayals of the office in film and television, that the presidency enjoys unchallenged power and can bend the world to its will. For all of his bravura posturing on Twitter, Tolkienesque rhetoric in relation to North Korea, and apparent determination to use his presidency simply to undo whatever President Barack Obama did, he has been largely unable to achieve anything thanks to the checks and balances of the American democratic system. Congressional recalcitrance and judicial independence have, thus far, proved their worth and demonstrated that the reality is considerably stickier (however, this is unlikely to provide much comfort to those groups of people who have been, or will be, victims of the racism, misogyny, homophobia and hatred that has been given license to operate by Trump’s election). Indeed, it is a reality representations of the presidency since the original publication of this book have been keen to explore: Scandal (Shonda Rhimes, 2012–18) ← xii | xiii → and House of Cards (Beau Willimon, 2012–), while different in many ways, share in their portrayal of the presidency a sense that it is a frustrating, almost thankless, role. The tiresome bargaining, compromise, shady deals and questionable allies one has to make are here for all to see, rendering the president a weak, impotent, frustrated individual who would either happily give up the job for love (Scandal) or resort to extraordinary levels of corruption to inject it with some power (House of Cards).3

Premiering on ABC the month before Trump’s victory, Designated Survivor (David Guggenheim, 2016–) tells the story of Tom Kirkman (Kiefer Sutherland), the Secretary of Housing and Development, who suddenly becomes President of the United States when the Capitol Building is blown up in a terrorist attack during the State of the Union. As the ‘designated survivor’ (the government official asked to remain in a secure location during this setpiece occasion in American political life who will become president should the unthinkable happen) he has the constitutional duty to assume the presidency after the attack. However, he has no experience of high office, let alone the ability to provide a response to the biggest ever terrorist incident on American soil. He is perceived as illegitimate, as weak, as intellectual rather than decisive (because – and, believe it or not, this is a common trope in presidential fiction – he wears glasses). However, unlike the recent, hyperviolent revenge fantasies Olympus Has Fallen (Antoine Fuqua, 2013) and White House Down (Roland Emmerich, 2013), Designated Survivor prescribes a sober, measured and careful response to the attacks. In many ways it appears to be a recalibration of the national ‘home invasion’ narrative that deliver fantasies of swift and uncompromising retribution: Kirkman is restrained, thoughtful and unwilling to act until he is absolutely sure of who has done this and why.

As with all film and television that in some way attempts to mirror reality, it is tempting to read Designated Survivor as a ‘comment’ on Donald ← xiii | xiv → Trump’s conduct in office. The only obvious similarity between Kirkman and Trump is that Kirkman is not a politician. Although he worked in government as Secretary for Housing and Development, he did so for altruistic reasons. He is not a ‘Beltway’ politician: he has no ambitions to climb the political ladder. He has only become president because of completely unforeseen, tragic circumstances. He is a public servant and assures us that he only got into this game to help people (further completing this picture is the fact that his wife is an immigration lawyer). The show is also at pains to reaffirm his status as a family man: a neat motif throughout is that Kirkman plays with his wedding ring while in the process of making life-or-death decisions in response to the terrorist attack. He refuses to endorse torture as a tactic of catching the people responsible and stands up for the rights of refugees when an immigration ban is proposed (the ban is successful, but he makes sure the refugees make it to Canada, rather than abandon them entirely). Despite safety fears, and a ricin attack, Kirkman refuses to allow elections to be cancelled or postponed, as electing a new Congress is considered the highest priority. Ensuring the stability and continuity of the Republic is his overriding aim. Kirkman deliberates, considers and ponders decisions before acting. He valorises the Constitution above all else, calling in the National Guard when a State Governor starts targeting Muslims shortly after the attack. He does not show off, grandstand; he is dignified, responsible, measured and moderate. The fact that Kirkman is played by Kiefer Sutherland speaks to a rather radical shift in the fictional presidential imaginary – Sutherland is perhaps best known in recent years for his portrayal of counterterrorism agent Jack Bauer in 24 (Joel Surnow, 2001–10), the television show that captured the post-9/11 zeitgeist and arguably provided popular cultural justification for the extreme policies pursued by the Bush administration. In Designated Survivor, Jack Bauer is president, but one who appears to have learned the lessons of his predecessors. He has the temperament necessary to defend the nation in turbulent times, and he will protect the constitution, liberal values and the rule of law.

This stands in in stark contrast, it must be said, to his real-life counterpart, who spent his first month in office undermining the judiciary over his ill-considered ban on travel from particular countries in the Middle East and North Africa, attacking celebrities like Arnold Schwarzenegger, and ← xiv | xv → making laughably overblown statements as though he was a character in a Hollywood movie (tweeting all in caps when his travel ban was struck down, ‘SEE YOU IN COURT, THE SECURITY OF OUR NATION IS AT STAKE!’). Trump’s status as a TV character who became president was confirmed by the fact that he fired the director of the FBI, James Comey, live on television. Kirkman’s characterisation suggests that fictional models of presidential heroism are becoming considerably more reliant upon people that have occupied the office in reality: Kirkman fancies himself a Kennedy, a Lincoln, or even an Obama, in his measured, thoughtful and liberal responses to national and international conflict. On the other hand, Trump appears more concerned with sharpening his reality TV persona for the political stage. Aggressive, arrogant and loud, Trump is a popular culture president occupying the Oval Office, whereas Kirkman is a real president occupying a fictional television show. It says much about the state of the real presidency that someone as ordinary and unflashy as Kirkman is the new ‘fantasy’ in which audiences can escape.

Escaping from the reality of Donald Trump’s presidency is perhaps the defining factor in the continued nostalgia for The West Wing (Aaron Sorkin, 1999–2006), which has enjoyed renewed interest as a result of its availability on US Netflix.4 The West Wing Weekly, a podcast featuring Hrishikesh Hirway and former star Joshua Malina, recaps each episode, commenting on how much politics has changed (largely for the worse) and interviews prominent figures from the show. As this book argued, at the time of its broadcast The West Wing was engaged in these processes, positioning the intellectual President Josiah Bartlet (Martin Sheen) as a fictional antidote to the apparently impetuous President George W. Bush. In so doing it offered a fantasy alternative to Bush’s ‘war on terror’ and suggested how the United States’ response to 9/11 might have been conducted in a more reasonable and measured way. Now added to this fantasy ← xv | xvi → are generous helpings of nostalgia, which could be viewed as problematic in a number of ways. Whereas previous retreats into presidential fiction could be viewed as necessary catharsis, the existential threat Trump poses to democracy renders such nostalgia at best a dangerous indulgence, a child-like inability to face up to political reality. The West Wing is, perhaps, a comfort blanket that one can ill-afford.

Furthermore, The West Wing bears many of the qualities to which Trump supporters are opposed: both celebrated and derided for its leftwing slant, it nonetheless has an often haughty, hectoring tone; its stars, members of the Hollywood elite, moonlight as political activists and their relationship with real politics was often uncomfortably close; it was (and is) celebrated by broadsheet critics and watched by the affluent, liberal middle-class. Rather than resort to the lazy, journalistic assertion that shows like The West Wing are ‘the reason Trump won’, it is possible to suggest that it speaks to a division within American society: it cannot be said that Aaron Sorkin’s vision of a liberal, intellectual presidency was designed to speak to the nation’s heartlands. That said, The West Wing Weekly is not unthinking in its look back at the programme, reserving particular criticism for the show’s often problematic gender politics, and offers a primer on ways in which it can be a functional tool in the ongoing processes of civic education. Looking at some of the real-world issues that the show explored in a contemporary light – like the Equal Rights Amendment, the death penalty and the racial problematics of the US census – The West Wing Weekly attempts to operate as an addendum to the new activism and an education in the processes of government. It cannot help but comment on contemporary politics, with Hiraway and Malina using the phrase ‘Trump Ay yay ay!’ whenever the politics of the show become eerily reminiscent of reality. In this, The West Wing nostalgia appears to yearn for a figure as responsible, intelligent and reassuring as President Bartlet, and for a time when politics was more ‘civil’.

While the previous iteration of this book argued that representations of women as occupants of the office are the ‘unfinished business’ of presidential fiction, there has been a relative boom in this area of late: President Elizabeth Keane (Elizabeth Marvel) in Homeland (Howard Gordon and Alex Gansa, 2011–), President Claire Underwood (Robin Wright) in House ← xvi | xvii → of Cards, President Claire Haas (Marcia Cross) in Quantico (Joshua Safran, 2015–) and President Selena Meyer in Veep (Armando Iannucci, 2012–18) are all recent examples of the fictional female presidency on television. Further work remains to be done on these iterations of the archetype, although it must be noted that House of Cards, Quantico and Veep perpetuate the tendency to position the female president as an ‘accidental’ leader, ascending to the highest office as the result of a constitutional manoeuvre rather than popular election. It is difficult to determine what impact Hillary Clinton’s defeat in 2016 will have on this aspect of the imaginary, and there are myriad factors as to why Trump won, but it would appear to confirm the notion that the presidency remains an office saturated in unreconstructed masculine ideology. Indeed, it is very depressing that the misogyny Clinton faced during her campaign in 2008 (explored in Chapter 6) was, if anything, worse in 2016.

During the administration of Ronald Reagan, the last time the orbits of celebrity and politics were this proximate, film and television rather retreated from fictional representations of the presidency. It is quite possible that a similar fate will befall the archetype in the Trump years: with a man taken from the screen occupying the real office, there will be perhaps little need to explore the presidential imaginary further until he is gone. Indeed, Trump’s victory spoke of a revulsion with politicians in general, and Washington, DC, in particular, and perhaps the widespread disgust with politics will make itself felt in fictional realms too. But we can no longer pretend that revelling in James Marshall’s (Harrison Ford) fisticuffs with Kazakh nationalists in Air Force One (Wolfgang Petersen, 1997), or cheering Josiah Bartlet as he issues a dressing down to a right-wing radio host in The West Wing, or laughing as James Sawyer (Jamie Foxx) struggles to master the use of a rocket launcher while being chased by terrorists across the White House lawn in White House Down, is inconsequential. What were once film and television’s improbable fantasies of what the President of the United States could, should and can be, have, with the election of Donald Trump, arguably become reality. Popular culture has metastisised in the political bloodstream: the discourses of celebrity, the gaudy sheen of reality television, the infantile longing for the strongman to rescue us, all filtered through the language and imagery of white, male supremacy ← xvii | xviii → to which film and television have long been willing contributors. While those of us with the privilege to critique what seemed to be such an unlikely eventuality – identifying the fictional antecedents of such a figure in popular culture, and discussing and debating Trump’s impact on the films and television shows yet to be made – will do so, I expect those without such privileges will be content merely to survive it.

Gregory Frame

September 2017

← xviii | xix →

1 Josiah Ryan, ‘“This was a whitelash”: Van Jones’ take on the election results’, November 9th, 2016, <http://edition.cnn.com/2016/11/09/politics/van-jones-results-disap-pointment-cnntv/index.html>, accessed September 2017.

2 Gregory Frame, ‘“The Real Thing”: Election Campaigns and the Question of Authenticity in American Film and Television’, Journal of American Studies 50/3 (August 2016), 755-77.

Details

- Pages

- XX, 328

- Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788742634

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788742641

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788742658

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788741439

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13206

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (February)

- Keywords

- nation political leadership society

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2018. XX, 328 pp., 11 b/w ill.