A Tale of Two Sisters

Life in Early British Colonial Madras The Letters of Elizabeth Gwillim and Her Sister Mary Symonds from Madras 1801–1807

Summary

Her younger sister, Mary, contented herself with descriptions of places, people and surroundings, not always complimentary to her peers. Behind all this was an undercurrent of anxiety about news from home, correspondence difficulties, war with France and a terrifying sepoy mutiny in Vellore. There was also a background of tension arising from the broken relationships between Elizabeth’s husband, judge Sir Henry Gwillim, and both his Chief Justice and the Governor of Madras.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Letters of 1801 and Commentary: Commentary

- Letters of 1802 and Commentary: Commentary

- Letters of 1803 and Commentary: Commentary

- Letters of 1804 and Commentary: Commentary

- Letters of 1805 and Commentary: Commentary

- Letters of 1806 and Commentary: Commentary

- Letters of 1807 and 1809 and Commentary: Commentary

- The Background of Politico-Legal Tension

- Postscript

- Bibliography

- Index

Illustrations

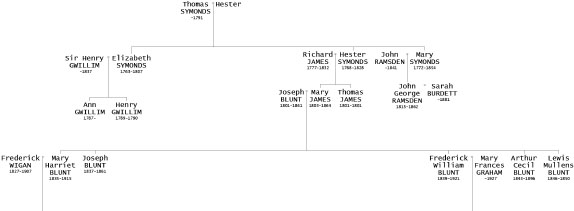

1Symonds family tree – earlier years

2Southeast view of Fort St George, Madras. Thomas Daniell 1797. (Author’s collection)

10Purple sunbird, by Elizabeth Gwillim. (Courtesy of the Curator of Manuscripts, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library, Montreal, Canada)←vii | viii→

12Hindu travellers, by Mary Symonds. (Reproduced by permission of the SADACC Trust, Norwich, UK)

Acknowledgements

Considerable thanks are firstly due to Michael Wigan and Ray Cocks. I must also express my gratitude to Victoria Dickenson, Anna Winterbottom and the staff of the McGill University Library and Collections, Montreal, to the staff of the British Library, London, particularly in the Asia, Pacific and Africa Collection, to Ben Cartwright of the South Asia Collection Museum, Norwich and to the staff of the Manuscripts and Special Collections Library, University of Nottingham. I would also wish to thank Rosemary Raza, Arthur Macgregor and, hitherto, the late S. Muhtu of Madras for general support.←ix | x→

Introduction

A squally and turbulent night had finally ebbed into a pearl-soft dawn rising calmly on the ship’s starboard side. The two ladies dressed in their respective cabins in the roundhouse of the ship, the Honourable Company’s East Indiaman, the Hindostan, and made their way up the steps of the quarter gallery to the poop deck. They had some inkling land was nearby, after months at sea, lately passing through miles of empty Indian Ocean. In the distance, to the left, they and the crew could just discern a grey line on the horizon and, before long, other ships riding at anchor in the roads outside what can only have been Madras. Late morning a 15-gun salute was made to the flagship, and was responded to with three cheers and, by midday, the anchor was dropped and a further, lesser, salute was made to Fort St George on the shoreline.1 After four months at sea they had at last arrived, in July 1801, although they still had to make the perilous journey ashore, crashing through the surf in an undecked masulah boat. Although made deliberately flexible, the two women quaked as it corkscrewed from wavetop to wavetop in the hands of ten spray-soaked straining oarsmen to the haven of the shingle, and to the rhythm of their chanting.

The two ladies were Elizabeth Gwillim, who had travelled with her recently knighted husband Sir Henry Gwillim, and her younger unmarried sister Mary Symonds. Sir Henry had been appointed Puisne Judge to the Supreme Court of Judicature at Madras, assisting the new, and first, Chief Justice, Sir Thomas Strange and another puisne judge, Sir Benjamin Sullivan. Also in their company were two young men, Mr Henry Temple and Mr Richard Clarke, both appointed as clerks to the court. During their seven years in Madras these two women wrote numerous letters home, sometimes lengthily, in which they described in detail their lives, ←1 | 2→occupations, interests and prejudices. Only these letters survive.2 There are none received by them from family or friends, but they remain a remarkable resource for an insight into day-to-day life in British Indian Madras, and by inference much of India, at the dawn of the nineteenth century. They were written at much the same time that Jane Austen was writing her novels in England, and although they can never compare for style, clarity and wit, they are fact, not fiction; they are history. The reality of being women meant that there was little description of political, economic or military events, and they are therefore a window into the social life of an otherwise male world, far removed from the certainties and reassurances of their English homeland. In a way this enhances their value, as they give us such a sharp perspective on life at that time, uncluttered by masculine concerns; a social anthropology of early British India. Letters are somehow a more revealing source than journals, giving a more personal and intimate glimpse of society; a hint of illicit disclosure in a relaxed and fluid style. Journals are often written with a suspicion of eventual exposure to public gaze, and may therefore be intrinsically more restrained.

Despite the limitations of commentary imposed by their sex, the two women’s letters, and lives, were also coloured by the experiences of Sir Henry Gwillim’s life in Madras. During the course of his Madras career he found himself increasingly at odds with the Governor and Council of this Presidency town, and also his senior colleague, the Chief Justice. As this progressed, so the two sisters became more distant from, and critical of, both the men and women of the British community, partly self-imposed and partly a polite ostracization. Until the middle of 1803 the governor of Madras was Lord Edward Clive who was son of the much better known Robert Clive of Plassey fame, but was himself rather less distinguished, preferring gardening to deliberating upon matters of state, which he left largely to his council. He was succeeded by Sir William Bentinck as Governor in 1803. The chief justice was Sir Thomas Strange, who presided throughout Sir Henry’s time there, and altogether for some fifteen years, apart from a period of absence in England in 1805 and 1806. The third judge, a puisne ←2 | 3→judge, like Sir Henry Gwillim, was Sir Benjamin Sullivan, and there were senior naval and military personnel and powerful members of council such as William Petrie. The rest of Madras’s working British population consisted of civil servants, traders, soldiers, young East India company writers, hopeful adventurers and a little human detritus that had washed up from unknown sources. It is difficult to ascertain the total numbers of British in Madras at the beginning of the 1800s, but it must have been a few thousand, many of them ordinary soldiers and sailors and not listed in the directories of the time, as neither was any woman. What is known, however, is that in the years 1801 to 1807, whilst the sisters were in Madras, the total number of British buried there was 3362, suggesting the overall population was not inconsiderable.3

Throughout the years that the sisters were in Madras there was increasing politico-legal tension. This is covered in more detail elsewhere. In summary, however, there was growing antipathy against the crown-appointed court by Governor Bentinck, who believed the charter of justice exercised by the Supreme Court might protect subversive Indians from prosecution and control, making insurrection easier. Doubtless it also curtailed some of the less respectable tendencies of the colonists. He would in fact have preferred to abolish the crown court and, after a while, even gained the support of the Chief Justice, Sir Thomas Strange. This antipathy to the crown appointed judiciary was a feature of life within the other Presidency towns in India. Sir Henry Gwillim opposed these attitudes, and supported the rights given to the Indian people as much as to the British, which led to an increasing gulf between him and the Madras establishment. This was not helped by a serious personality clash between him and both Bentinck and Strange, reinforced by Gwillim’s irascible and prickly temperament. In the end, charges were laid at his door, and his career in India was cut short by his recall in 1808, alone, his wife Elizabeth having died in 1807.4, 5←3 | 4→

These events are of considerable relevance to the lives of his wife, Lady Elizabeth Gwillim, and her sister, Mary Symonds. Both arrived in Madras, full of excitement and anticipation, and plunged themselves into the social whirl and visual delights of a strange and fascinating culture. Elizabeth became deeply involved in numerous interests, and immersed herself in the country and its people, whereas Mary concentrated on the European life. She was after all single, and her best future lay in finding a suitable husband, for the lives of women in those days were completely dependent on the patronage of men. As Elizabeth wrote, ‘I shall leave the White people to Polly and tell you a little about the Black people.’ Polly is of course Mary, and at first sight her letters seem superficial, even flighty, but closer inspection reveals a serious and intelligent analysis of the people and events of the time, which sometimes verged on tart opprobrium aimed at her peers, as the family becomes more detached from the social hub with the gradual fall from grace of Sir Henry. Elizabeth, on the other hand, had no real reason to plunge herself into the life of British society, other than unavoidable dinner engagements and balls, because she was married, with a household to run, and a fiercely intelligent interest in the Indian world around her. She wanted to know as much as she could about Indian culture, religion and daily life, and learnt the local language to this end. Despite this, both women became more defensive as life became more politically strained for Sir Henry, and they felt themselves to be slightly ostracized by the society in which they had by right of seniority and precedence found themselves. As relationships became subtly more tense, one can detect an increasing asperity within the two sisters’ letters; a waspish inclination to disparage the behaviour, origins, attitudes and abilities of their peers. Eventually they were found to be upholding Sir Henry’s politico-legal contentions. The two women had a close and friendly relationship with Thomas Strange and his wife in the initial years, but this became more distant and strained as events followed their course. There was particular irritation at Strange’s sudden and unexplained return to England in 1805, which was believed to be self-serving, and this eventually proved correct. It had placed a great burden of work on Henry Gwillim’s shoulders, in that he was effectively covering all the court work alone for nearly two years.←4 | 5→

It is interesting that the East India Register and Directory for 1803 and 1804 shows Lady Gwillim to be a directress of the Female Asylum (Orphanage), along with Lady Clive, the then Governor’s wife, which was very much to be expected for women of their standing within that community. Lord Clive was governor of the institution. By 1805 Lady Clive’s place had been taken by Lady Bentinck, whose husband had become governor, but Lady Gwillim’s name was no longer present, although by right it should have still been.6 It was possible that she was nudged out of her role because of the differences between the two husbands, or that she resigned graciously in support of her husband.

Elizabeth was interested in horticulture, which developed into a desire to learn botany, in which she received instruction from at least two notable local botanists, Dr Johan Rottler, a French missionary-botanist,7 and Dr James Anderson, Physician-General in Madras,8 to the extent that she had at least one specimen named after her: Gwillimia Indica Rottler. In addition, and most important of all, she and Mary were consummate artists. Some of Elizabeth’s extraordinary watercolours are held in the Blacker-Wood Library at McGill University, Canada, having been found in London in the 1920s. These are mostly ornithological, some large, measuring three by ←5 | 6→two feet, and therefore clearly life-size or more, and exquisitely executed, with well-preserved colour and line.9 The most interesting thing is that they precede the work of John James Audubon by more than twenty years. Somehow they seem a little more natural, and perhaps this has something to do with Audubon’s technique, which was to shoot the birds first and hold them in place with a metal framework. Elizabeth, however, usually painted from life and had to work quickly because the birds would not eat or drink whilst captive. She had a very skilled, but somewhat self-willed, elderly assistant who was able to keep the birds peaceful, and relatively still, while she painted. They were then released. Inevitably she had to paint shot specimens from time to time, but she still had to work quickly as they quite quickly became unlovely companions in that heat. She also painted botanical specimens and some other animals, but most of these seem to have been lost. Mary was not supposedly such an accomplished artist, but she painted very finely, and particularly concentrated on Indian life and landscape. Much of her work is held at the South Asian Collections Museum in Norwich. Both their letters often make reference to George Samuel, and it is clear that they wrote to him about their drawing and painting and so must have known him well, and had very probably received instruction from him in England. George Samuel (1770–1823) was a well-known landscape painter of the time, who exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy.10

The interest in Indian matters was profound, and Elizabeth’s observations on the character of the Hindu people were perceptive and valid. In October 1801 she wrote, ‘They are the mildest people in the world. They go on praying to their god, sowing rice, weaving cloth, and eating curry just in the same way as they have done these three thousand years.’ Little has changed, in a rural context at least, in the two hundred years since. In the early years they were both fascinated by the customs, dress, foods, flora and even the climate, apart from the dreaded ‘land winds’. Despite the pleasure in the food available, they were often asking for special requests from home, such as hams, ketchup, confectionery and unavailable herbs and, besides ←6 | 7→edible goods, they would request English seeds, clothing, hats, china, jewellery, even fire irons and especially drawing paper and watercolours. The time from request to delivery cannot have been much less than a year. At the same time they were sending plants, seeds, presents of shawls, fabrics and various trinkets to their family and friends. Elizabeth was much intrigued by Indian history and tried to describe some of the particularities of Hinduism to her mother. She also described, in some detail, the various Hindu festivals that she attended; the intricacies of dress and dance, the ritual, fireworks, illuminations and finely detailed carving of the carriages, all fascinated her. In describing Indian religious dance she wrote, ‘Their dancing is very little like ours; they never step upon the toes but keep the knees bent, and tread on the outside of their feet and move in a very small space ……… they dance for an hour within the space of a sheet of paper, the feet all the while in constant motion.’ It would be hard to improve on this for accuracy of observation. In order that she could more deeply study the history and religion of the Indian people, she learnt competent Telugu, the language of the region, and she could also write it adequately (see note 11 of 1801, page 29).

Much of the correspondence is studded with chatter about family and friends, and occasional less than flattering comments about other Madras residents, especially from Mary, and especially after the initial honeymoon period had waned. Names are scattered through the letters, and most are family or close friends. Others are young men travelling home, or officers on East India Company ships, who acted as couriers for letters and packages. Some of these young men, and others recently arrived in India, such as William Biss, would stay in the Gwillim household, often for long stretches. They would be company for the male members of the household, such as Sir Henry Gwillim himself, and his young protégés Richard Clark and Henry Temple. Elizabeth and Mary also much enjoyed hosting these young men. Mary, because she was nearer their age group, and considering marriage, albeit rather languourously, and Elizabeth because she was childless, her husband was overworking, and was often absent, and her maternal disposition encouraged her protective instincts. Young men were often bored, isolated and lonely and unsurprisingly susceptible to the charms of Indian women and, more so the Anglo-Indian, who were frequently ←7 | 8→very beautiful and, if born of a man of means, reasonably well educated. In Calcutta at that time, three-quarters of young bachelors kept at least one bibi, or mistress. Half of the children baptised there in the Anglican churches were illegitimate, and of mixed parentage.11 One-third or more of all British wills left all a man’s possessions to one or more bibis, or their offspring.12 It is unlikely Madras was much different. Elizabeth, and many such contemporaries, tried to protect young men from these temptations. They and their contemporaries were only a small factor in the gradual suppression of the bibi and of the Anglo-Indians. Much more important was the intolerance demonstrated by the growing body of church ministers and missionaries, and the gradually increasing exclusion of the Anglo-Indian from government employment.13

If women were concerned about young men, the age of girls about to be married was another consideration, although one they could do less about. The age of consent for a girl was much lower at that time and, although they often thought a girl too young, they railed against the thought of decrepit men aged 50 to 60 years marrying girls of 15 or 16, which was common practice at that time.14 Although appalled by the prospect, they blamed the girls as well, ‘their own sordid dispositions have made them prefer age and riches when they might have married men suitable to themselves in years and with fair prospects, but without much ready money’.

The unabridged letters contain 155,000 words, which is a great deal of quill and ink for two women. On one occasion Elizabeth wrote a letter that was almost 10,000 words in length; more a dissertation than a chatty note. The need to write was paramount, partly out of a desire to share their experiences but also tacitly, or sometimes not, to invite a reply. News from home was desperately sought, and all the time there was that lurking anxiety that the next letter might reveal an awful event. Doubtless the feeling ←8 | 9→was the same amongst their English family, and always there was the ever present, but unspoken, fear that one might never see loved ones again. So the scratching of quills was a frequent sound, but most especially when word passed around that a ship was due to sail, and letters were hastily gathered to be put into the packet for that ship. ‘I have three people standing by me and hurrying me to conclude.’ This often led to hasty scrawling and dubious punctuation. Awaiting a reply could entail months of agonized silence while the adverse monsoon winds, or one of the other hazards of the sea, prevented ships reaching the Coromandel Coast. A gap of at least four months without correspondence was the norm in the winter months, and then letters that were several months old could arrive in bundles of six or more from one correspondent. Although the sisters claimed that even a few words were welcome they, in fact, preferred much more in the way of news. There is in the letters a continuous underlying current of homesickness. ‘A ridiculous little shabby note from James, for which he may expect a good trimming when I have more time to write. This letter to come 15,000 miles consists of six lines of business, and two more of apologies for not making it shorter!’

Another major occupation, and point of comment, was the management of staff. Everyone had servants, and it was commonplace, even usual, to have ‘half a hundred’ as in the Gwillim household. The roles were legion, from that of the Khansaman, who was Muslim, who purchased provisions and superintended the table, down to the Chaprasi who acted as a footman and runner, carrying messages. In between these they employed dishwashers, clothes washers, horse carers, grass cutters, water carriers, coolies, palanquin carriers and so on. Language difficulties were usual, which is one of the reasons why the women learnt a local tongue. An important initiator of a requirement for so many servants were the arcane religious and caste differences between Hindu and Muslim, which caused great difficulties in food handling for obvious reasons. Higher caste Hindus would not even touch a clean plate in case it had been defiled, for fear of loss of caste. The pariahs,15 or lower caste individuals, were of course available ←9 | 10→for any unpleasant job that needed doing. The two sisters’ feelings about their staff were cautious but amicable. Like everyone else they depended on them hugely; they wondered at their practices and lifestyle; they didn’t entirely trust them not to pilfer, but they greatly admired their consideration and kindness.16

Within the letters two circumstances appear that are not a feature of the normal social landscape. The first is their ability, as women, to visit a zenana.17 Mary’s description is therefore highly unusual, as it was forbidden for any man other than husband or brother to enter a zenana, and there are therefore few first-hand accounts even by women. Mary’s comments, although given with her usual offhand and slightly disdainful manner, thus become very revealing. The other situation was unique, and that was the Vellore mutiny, a little discussed event from 1806 which preceded the Great Uprising of 1857 by half a century. This bloody and violent sepoy rebellion, only 85 miles away, is described from contemporary accounts by both sisters whilst, like the other British residents of Madras, fearing increasingly for their own lives. The underlying causes are reported, and many of the details, and there is a reassuring demonstration of sympathy with the point of view of the Indian sepoys for reasons which seem today very reasonable, but obviously didn’t to some supervisory authorities at that time. Their reaction may have been partly enhanced by the deteriorating relationship with Lord Bentinck, knowing that he was held partly ←10 | 11→responsible for the mutiny’s occurrence, and as a consequence recalled by the Company’s Board of Control.

When they arrived in India, Elizabeth was aged 38, having been born in Hereford in 1763. She married Sir Henry Gwillim in London in 1784 and it would appear that she had two children, Ann Gwillim born 1787 and Henry in 1789. There is no mention of any children with these names in the correspondence, only the children of her sister Hetty at home, and those of friends. It is likely that they both died in infancy, and this is confirmed for Henry. When Elizabeth arrived in India she had been married for 17 years and it wasn’t to be for much longer. In December 1807 she died somewhat unexpectedly, with no clear cause being recorded. Her letters reveal a relapsing febrile illness which she treated with cinchona bark; effectively quinine. It seems possible, therefore, that her death could be attributed to a malaria-related illness, such a common scourge at that time, although typhoid, dysentery or some other infectious illness could have been the culprit. She was buried under a rather austere flat headstone, inscribed in Latin, just inside the entrance to St Mary’s Church within Fort St George. Every visitor walks across her bones without realising the remarkable talent and intelligence of the person over whom they are passing. Ten months later, in October 1808, Sir Henry, his still unmarried sister-in-law Mary, and good friend Richard Clarke, took passage home in the east Indiaman Phoenix which, after a perilously stormy voyage, reached Capetown in January 1809. Romance flowered amongst the cut-away masts, rent topsails and sea-swept quarterdeck and later that same year Mary married Captain John Ramsden, the commanding officer of her ship home. Five years later she had a son. Sir Henry Gwillim did not languish too long in the isolation of widowhood and married Elizabeth Chilman in 1812. One must suppose she did not live up to her name as he lived until 1837, reaching an age of almost 80 years. Interestingly Richard Clarke, then a civil servant in the East India Company, seems to have retained a lifelong friendship with Mary and her new husband. He was to become a significant legatee, along with Mary and one other relative, in John Ramsden’s will of 1841. He had also married a family friend, Mary Thoburn, in 1809.

Details

- Pages

- X, 372

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800791688

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800791695

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800791701

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800791671

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17943

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (July)

- Keywords

- Life and accomplishments of women in early British India Early colonial social history Outstanding British women of the era A Tale of Two Sisters Patrick Wheeler

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. X, 372 pp., 11 fig. col., 4 fig. b/w.