Labour Law Reforms in Eastern and Western Europe

Summary

The current selection of academic contributions intends to provide an overview of recent developments in the legal regulation of labour markets in Eastern and Western European countries. The authors’ contributions could not cover all the aspects of the current state of recent reformist efforts on the labour markets. However, by picturing separate developments in different European countries, it intends to assist in identifying regional similarities. Furthermore, it provides opportunities for exchange of ideas, experiences and practices for shaping labour law both at European and national level.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Introduction (Tomas Davulis)

- Part One. General Trends

- Labour Law Reforms in the Eastern European Member States (Tamás Gyulavári)

- The Dynamics of Slovenian Labour Law (Polonca Končar)

- Main Features of Lithuanian Labour Law Reform 2016 (Tomas Davulis)

- Labour Law Reforms in Germany (Manfred Weiss)

- The Battle about Labour Law Reforms and the Long and Winding Road towards the Competitiveness Pact in Finland (2015-2016) (Niklas Bruun)

- Part Two. Industrial Relations

- European Wage-Setting Mechanisms under Pressure (Paul Marginson / Christian Welz)

- The Transformations of Employment Relations (Daiva Petrylaitė)

- The Lithuanian Social Partnership Model and its Impact on the Development of Labour Law (Rytis Krasauskas)

- Standards for Employee Participation in Decision-Making Processes (Information and Consultation Rights) and their Implementation in Candidate Countries for EU Accession in the Western Balkans (Otmar Seul)

- Part Three. Individual Employment Law

- Individual Labour Law Reforms in Belgium and the Role of Certain Socio-Economic Factors (Wilfried Rauws / Evelien Timbermont)

- From Dismissal Law to Re-Employment Law (Marc De Vos)

- Dismissal by Reason of Redundancy for the Company’s Needs in the latest Labour Reform in Spain (Mª Cristina Aguilar Gonzálvez)

- Labour Law Reform (Andrzej Marian Świątkowski)

- New Forms of Work (Robert Rebhahn)

- Occupational Health and Safety Requirements and Flexible Organisation of the Working Time (Gaabriel Tavits)

- New Limits of ICTs at Work (Lourdes Mella Mendez)

- A New Approach of Flexicurity (György Kiss)

- The Freedom of Contract in Lithuanian Labour Law (Tomas Bagdanskis)

- Non-competition Agreements (Beata Martišienė)

- Business Transfer in the Context of Labour Law Reform (Eglė Tamošiūnaitė)

- Arbitration Agreements in Individual Labour Law (Arnas Paliukėnas)

- Labour Rights Defence (Gintautas Bužinskas)

- Part Four. Social Security and Labour Market Policies

- The Recent Reform of the Social Security System in Italy (Silvia Spattini)

- The Analyses of the Legal Measures Taken to Combat Unemployment (to Boost Employability) among Older People According to the Last Amendments of the Polish Law on Employment Promotion and Labour Market Institutions (Tatiana Wrocławska)

- Reform of the Labour and Social Security Law in Latvia with Regard to the Rights of Employees in Connection with Parental leave (Kristīne Dupate)

- The Legal Framework of Unemployment Benefits in Russia (Olga Chesalina)

- Unemployment Benefits System in Lithuania (Audrius Bitinas)

- Series Index

Labour Law Reforms in Eastern and Western Europe

Unlike other branches of law, labour law lacks the legacy of centuries-long tradition. Even if the main objectives of the labour law do not alter, changes in detailed legal regulation and case law within a short span of time may be impressive. Most fundamental transformations are triggered by structural changes in the economy, but they could also emanate from pressure to reshape the balance between capital and labour in response to temporary economic difficulties or in reaction to ongoing changes in technological and organizational patterns of work.

The dynamism of legal regulation of employment is worthy of the close attention of academics, social partners and those involved in drafting and applying social legislation. The increased competition of national labour markets which goes along with fierce international economic emulation intensifies the debate about trends and developments. Consequently, it may result in either significant or in less ambitious changes of the domestic legislative framework of employment and industrial relations.

This selection of articles traces recent developments in labour law and in related areas like social security in European countries. Some of the developments may truly be labelled as ‘reforms’ but the majority are examples of a gradual evolution, which is necessary in order to overcome errors or shortcomings or to provide the necessary adaptation to technological, social or economical reality.

Part one is devoted to general trends in recent amendments of labour law at national level. First of all, Tamàs Gyulavári presents a broad overview of the reforms in Eastern Europe in his identification of three stages of labour law. The first reforms were needed to adjust the former Soviet Labour Codes to the needs of a market economy, either by several amendments to the original Labour Code (e.g. in Poland and Czech Republic), or by passing a new Labour Code (e.g. in Hungary in 1992). ← 11 | 12 → The second cluster of reforms served to implement EU labour law before EU accession. The third, most recent reforms are closely connected to the changing world of work, the financial crisis and also the political will to increase the employment rate. When dealing with the latter, the author critically assesses the increased enthusiasm in Eastern European countries about the need to promote various forms of atypical employment. He also draws attention to the phenomenon of self-employment and predicts that the danger of bogus self-employment will be among major concerns which have to be addressed at national level.

The most recent example of overall national labour law reform is presented by Tomas Davulis. He explains in detail the background to the re-codification of labour law in Lithuania and analyses both the changes needed to modernize the legal attitude towards the employment relationship and the measures to balance the desired flexibility for business with new forms of employee protection. In his the new legislation shall modernize the employment relationship in a much broader perspective – to revive the spirit of cooperation between the parties both at individual and collective level, to increase the judicial protection of employees, to allow for wider acceptance of technologies, investment in human capital and respect of the employee’s personality and his/her family commitments.

On the other hand, Polonca Končar refuses to use the word ‘reform’ when addressing legislative changes which are not of an in-depth nature. Instead she reminds us of the innate dynamism of the labour law to adapt to political, economic and social development. From this perspective she assesses recent developments in the field of the labour market and labour law – changes aimed at both reduction of employee protection (e.g. lowering costs of dismissals) and providing new forms of protection (disincentives for fixed-term employment, limitation of temporary work, broadening the scope of protection for the self-employed).

Detailed analysis of individual and collective labour law reforms in Germany is provided by Manfred Weiss. He suggests that German labour law is moving not in the direction of deregulation but to a re-regulation, stabilizing the already existing protective schemes. Recent amendments strengthened the institutions of collective bargaining and co-determination, whereas the reforms on minimum wage, fixed-term contracts, part-time work and temporary work agreements have provided new shapes for individual employment law. The author concludes, that the labour law reforms in Germany are not an expression of a well-planned strategy but are rather reactions to upcoming needs on the labour market. However, ← 12 | 13 → the legislator rarely initiates changes but shapes legislative proposals on the basis of intensive dialogue with the social partners.

Niklas Bruun’s paper presents the efforts to reform labour laws in Finland within the framework of a so-called package of competitiveness which aims at reducing labour costs by way of sectoral collective agreements. The involvement of social partners in the reformist agenda seems to be a true test for of the Finish labour law system in which the collective bargaining, which was initially designed for sharing benefits, was used instead to manage deduction of protection and cuts in remuneration.

The second set of contributions (Part Two) deals with issues of industrial relations, which in Eastern Europe tend to be known as ‘collective labour law’. First of all, Paul Marginson and Christian Welz reveal tendencies in collective wage-setting mechanisms across Europe since the onset of the economic crisis of 2008. The pressure on national collective bargaining systems to be more ‘marketized’, in other words to be more responsive to economic and competitive circumstances, resulted in increased decentralization of bargaining. Due to crucial differences in their institutional arrangements the countries have taken different paths to create more room for company-level arrangements in the multi-employer bargaining systems. Authors believe that a single prescription or an enforced solution would not be efficient and could also weaken the established mechanisms of collective wage-setting.

In her contribution Daiva Petrylaite explores the changing role of social dialogue in the contemporary world of labour. She reflects on the importance of the social partners in the public decision-making process in the European Union and explains the differences and difficulties in the functioning of social dialogue in Central and Eastern Europe. This is a region where social dialogue is less developed and governments were allowed to take unilateral decisions during the economic crisis thus neglecting the idea and the principles of social dialogue.

Some countries experience more targeted reforms in the area of industrial relations. The implementation of information and consultation acquis is one of the topical issues in EU candidate countries. Otmar Seul investigates the legislative changes and practices in Albanian labour law related to the creation of a participative system at enterprise level. The new form of employee representation was intended to improve the environment for more democratic decision-making in companies but the new rights of information and consultation are still alien. ← 13 | 14 →

The Lithuanian model of social partnership has been presented by Rytis Krasauskas. After discussing the general features of the current legislative framework of social partners, he concludes that there is a considerable gap between the text of the law and the actual situation. It is not only unbalanced legal constructs that contribute to the stagnation of social dialogue and the absence of collective agreements, but economic, political and even psychological factors are also responsible.

Part Three is devoted to the various aspects of employment law to what is sometimes referred as individual labour law.

First of all, Wilfried Rauws and Evelien Timbermont present the series of measures which were introduced in Belgium with the main purpose to combat unemployment and provide for more flexibility. Some of those reforms were of a permanent nature while others were manifested as temporary. In the future new changes in the areas of working time and the reintegration of disabled employees are to be expected. Another perspective on Belgian labour market reforms was shown by Marc De Vos who analyses the change in dismissal protection from both a general perspective and from the perspective of national labour law. He argues that even some successes on the pathway to flexicurity do not alter the deficiencies of the fragmented reforms. The author advocates for a comprehensive reform of dismissal law towards re-employment law which also involves a change of paradigm in the philosophy of dismissal protection and active involvement of all stakeholders.

The legislators’ responses to economic difficulties frequently result in changes to the dismissal protection of employees. Cristina Aguilar Gonzálvez analysis the changes in economic, technical, organizational or production-related reasons as justifications for dismissal of workers after the 2012 labour law reform in Spain. The new case law may recognize a greater freedom of choice for companies but it is important to ensure the requirement of a causal relationship between the company’s economic situation and excessively large workforce, when applying also the test of proportionality.

By exploring recent changes in Poland with relations to fixed-term contracts, Andrzej Marian Świątkowski identifies the tendency of convergence of the two opposite sides of fixed-term employment – stability and flexibility. The author explains in detail the Polish legislator’s intention to align fixed-term contracts with contracts for an indefinite term while, at the same time, creating room for conclusion of fixed-term contracts for work of a permanent nature. ← 14 | 15 →

New forms of work constitute significant challenges for many European states. New types of engagement of workforce such as on-demand work, posting of workers, work of self-employed persons are analysed by Robert Rebhahn from the Austrian perspective. He rightly argues that the European Union struggles to address the new problematic forms of work with the new legislative instruments. A broader socio-political debate is needed on what role the labour law and social security law of the European Union should play under the new economic paradigm – should it aim at stabilizing the differences in conditions that exist between different regions and countries or help to equalize these conditions. Gaabriel Tavits adds to the discussion with his question of whether flexibility is still important in the European Union? He supports the more active role of the European legislator arguing that the new forms of employment should be subject to the current occupational health and safety requirements. Similar thoughts may provoke an analysis of how dramatically technological advancements change the patterns of work. In some countries the legal adjustment of employee protection remains in the domain of the case law whereas in some other countries we may witness pro-active engagement of social partners and legislators to address this topical issue. The contribution of Lourdes Mella Mendez is devoted to the new individual right of an employee – the right to disconnect.

New ways on how to approach the phenomenon of flexicurity were presented by György Kiss. After providing an in-depth theoretical analysis into substantial attributes of the employment relationship, namely the legal subordination of the employee and long-term nature of this relationship, the author suggests new ways of interpretation which would serve both flexibility as well as protection of the employee’s legal status. The theory of the contract of employment as a relational contract integrates the elements of commercial contract into labour law and this could have great potential for new developments of individual labour law.

The interplay of labour law and civil law instruments may be of importance in times of desired dynamism of labour law. In many countries labour law functions by way of implementation of restrictions of individual freedom of the contract and autonomy of the parties. The deficits of strict and rigid national legislation on individual employment contracts may sometimes be corrected by the judiciary. Using the examples of the application of the 2002 Lithuanian Labour Code in courts Tomas Bagdanskis provides us with evidence of the reformist role of judges making ← 15 | 16 → law in circumstances when legislators fail to adapt necessary changes in the new context of the socio-economical environment. Another civil law instrument – non-competition agreements and their way into the employment contracts was discussed by Beata Martišienė who supports the idea that a timely balanced legislative approach is more desirable than judge-made rules when dealing with these new phenomenon for the better protection of employees.

Labour law reforms may be employed not only to introduce the measures necessary to boost employment, flexibility and adaptivity. Eglė Tamošiūnaitė provides an analysis of how the Lithuanian legislator advanced the implementation of the transfer of undertaking directive. Arnas Paliukėnas presents his insights on the new possibilities to arbitrate individual employment disputes. Gintautas Bužinskas presents a comparative analysis of the individual grievances procedure in the three Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), providing examples of the similarities of the pre-trial procedure in those countries.

Part Four of this collection is devoted to the accompanying branches of social security and labour market policies. The majority of changes in this area were inspired by implementation of the principles of flexicurity or provoked by the need to compensate the reductions in employee protection. The greater coverage of the new forms of employment, increased benefits and new family-related accommodations are among popular issues in the reformist debates. Silvia Spattini presents the latest changes in Italy’s social security system which was reorganized with the objective of greater equity through the rationalization and universalization of benefits. The Polish legal novelties towards combating unemployment among older people are presented by Tatiana Wrocławska. The reformist changes with regard to greater articulation of childcare leave in Latvia are highlighted in the contribution of Kristine Dupate. An overview of the legal framework of unemployment benefits in Russia is presented by Olga Chesalina and in Lithuania by Audrius Bitinas. They reveal the fundamental problems of the Eastern European unemployment benefits system – the low level of benefits and low coverage. Against this background, implementation of flexicurity policies which aim at balancing flexibility with state support for the unemployed seem to be rather problematic. It may succeed only if reforms of the unemployment benefits system were included in the complex reform of social insurance, labour relations, social assistance and employment. ← 16 | 17 →

This selection of articles cannot cover all the aspects of the current state of recent reformist efforts on the labour markets. Instead, by picturing separate developments in different European countries, it intends to assist in identifying regional similarities. Furthermore, it provides opportunities for exchange of ideas, experiences and practices for shaping labour law both at European and national level. ← 17 | 18 →

Labour Law Reforms in the Eastern European Member States

Towards a New Structure of Work Relationships?

Abstract

The post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe are still the least developed EU Member States. These countries have very similar labour law traditions, labour market conditions and economic development. However, there are also remarkable subregional differences (e.g. Baltic States, Balkans and Visegrád group1), and their economic growth has been quite divergent since EU accession. At the same time their labour law reforms have served identical aims. These labour legislations had to meet two fundamental demands in the last 20 years, firstly the change from a socialist planned to a market economy (1990s), and secondly the implementation of EU labour law as a legal condition of EU accession (2000s). The most recent Eastern European labour law reforms are connected to the changing world of work, the financial crisis and the related objective to increase employment. The paper focuses on the evolving new structure of work relationships, respectively its impact on these national labour laws and labour markets. Two potential sources of employment flexibility are analysed in this regard: atypical employment contracts and the various forms of (genuine, false) self-employment. Atypical employment contracts do not play an important role in this region, despite the detailed regulation of atypical employment enforced by labour law harmonization. Typical, full-time and indefinite-term employment contracts are still the dominant employment relationships. The need of employers for flexibility (meaning cheaper workforce) is met by other sources, especially false self-employment, which has rapidly expanded in spite of various legal and administrative measures. Thus, increasing numbers of workers are leaving typical employment, but the parties opt rather for non-employment forms of work instead of finding flexibility in an atypical employment contract. Therefore, the ← 21 | 22 → paper analyses the aims and conditions of recent labour law reforms and their impact on the legal framework of legal relationships aimed at work.

Keywords: Labour Code, atypical work, fixed-term contracts, false self-employment, economically dependent work

Introduction

The 11 Eastern European states joined the EU in three waves in 2004, 2007 and 2013. The analysis of labour law reforms in this group of countries seems to be a relevant topic, since they show remarkable common characteristics. Similarities within this group of Member States include the legacy of socialist law and economy, the existence of a Soviet type of Labour Code, akin to economic development and labour market conditions. All of these national labour laws have constantly changed in order to, first, establish decent employment conditions for a market economy, and later to implement all EU law requirements in this field. Recent reforms have faced the new challenges of the low employment rate and its increase by flexibilization of labour law. However, this is also a challenging topic, since there are a number of national and sub-regional peculiarities (e.g. compare Bulgaria with the Czech Republic or Estonia).

The large topic of labour law reforms would exceed the potential of this paper, hence it highlights solely the development of legal relationships aimed at work. First, labour law reforms in general will be described. This introductory part is followed by the picture of atypical employment relationships, respectively the evolution of self-employment, false self-employment and the potential regulation of a third type of labour law definition (economically dependent work). The aim is to understand and predict changes in the legal employment framework in the region.

1. Labour law reforms in the Member States of Central and Eastern Europe

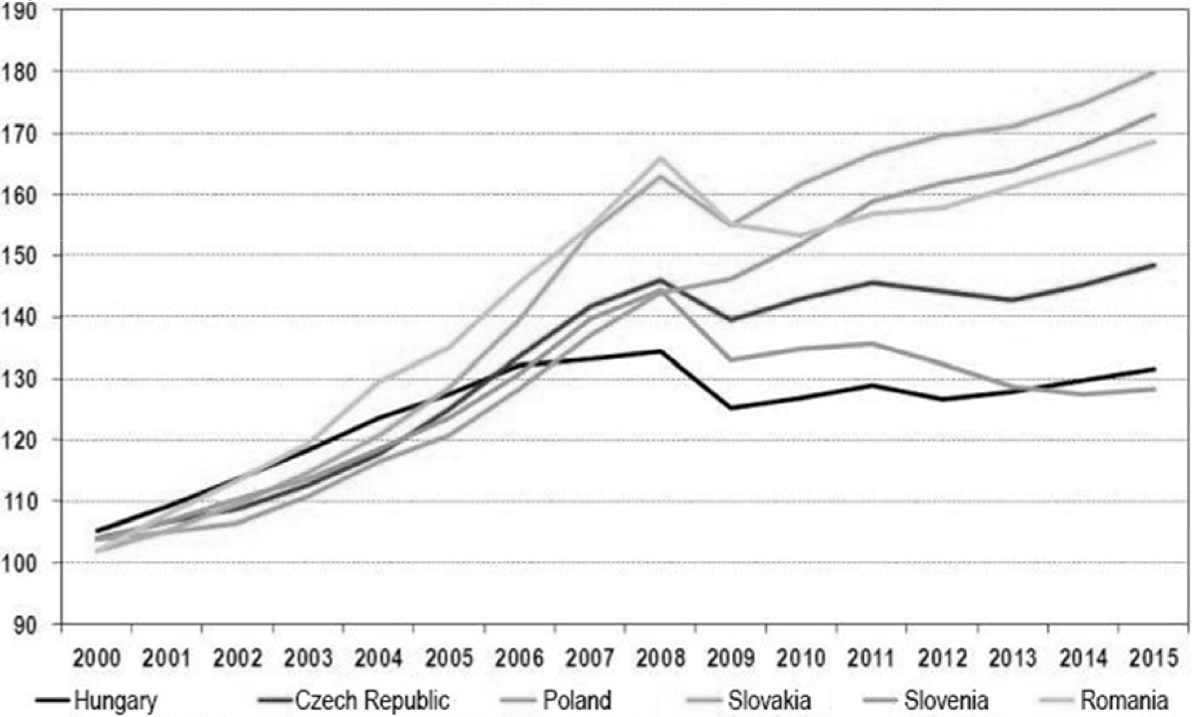

The post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe joined the European Union in three waves between 2004 and 20132. In spite of their fast overall economic growth, these are still the poorest EU Member States, representing only 45–84% of the EU average (Bulgaria ← 22 | 23 → with 45 and the Czech Republic with 84% in 2015)3. However, there are noteworthy differences between the economic development and GDP growth of certain subgroups of countries in the region. The table below shows, that the poorer countries in the group (such as Poland or Romania) have shown faster improvement than the former ‘champions’ (Slovenia or Czech Republic). Consequently, the most dominant trend is economic equalization in the region.

GDP per capita in selected eastern European Member States between 2000 and 2015 (compared to national 100% in 2000)

Source: http://budapestbeacon.com/economics/gki-issues-economic-outlook-for-hungary-in-2015/15695

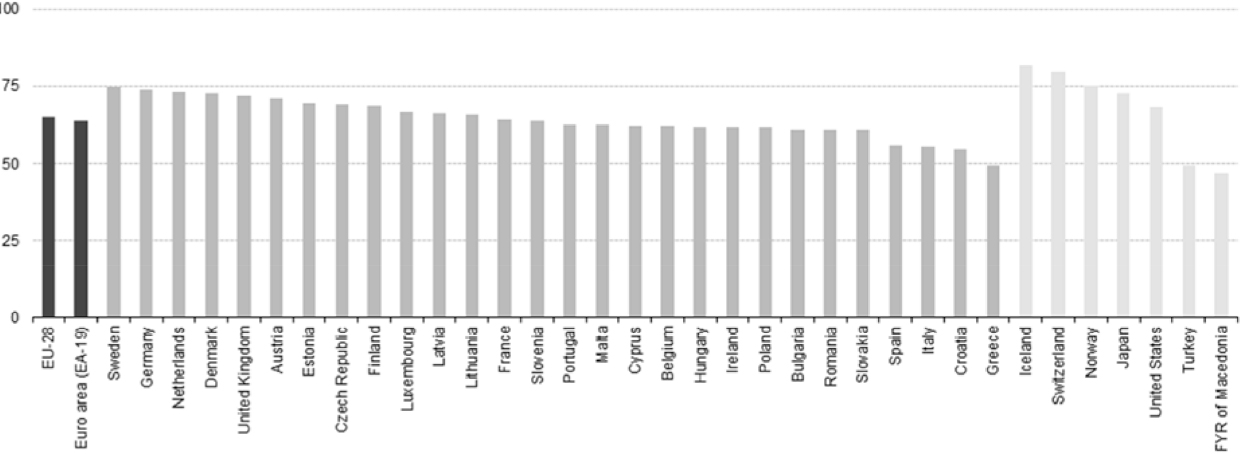

Concerning employment policy, the low level of employment has always been and still is the most crucial problem of these labour markets. After the Southern European EU Members, the Eastern European countries have the lowest level of employment in the whole EU, and the Czech Republic is the exhilarating exception. In Hungary, the employment level seems to be around the medium level; however, this relatively good employment level is reached by including around 250,000 public workers and all Hungarians working abroad in the employment rate. ← 23 | 24 →

Employment rate, age group 15–64, 2014 (%)

Source: Eurostat (online data code: Ifsi_emp_a)

Consequently, the growth of employment seems to be the primary aim of employment policy and labour legislation in all these countries. Certainly, there are other secondary objectives in several countries, such as handling the global crisis and resolving demographic problems in Poland (Skupień, Łaga and Pisarczyk, 2016), as well as renewing the legal text fragmented by too many amendments in Hungary (Gyulavári and Kártyás, 2016). At the same time, the creation of jobs by flexibilization (deregulation) of national labour law looks like the regional trend, as is best demonstrated by the Hungarian labour law reform in 2012 (Gyulavári and Kártyás, 2016)4.

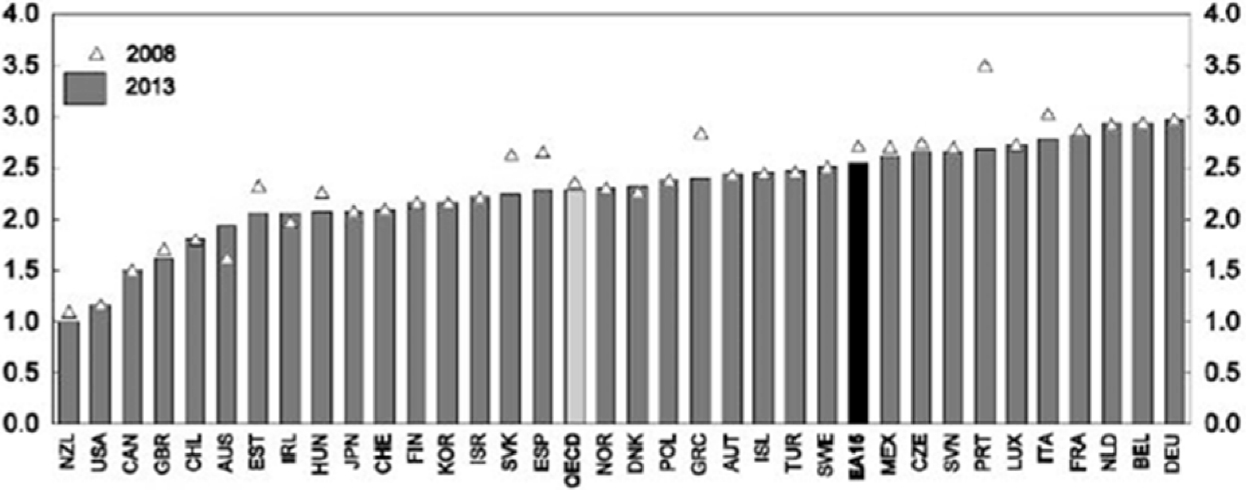

However, employment protection is relatively weak in most of these Eastern European Member States, particularly in comparison with more developed OECD countries (see table below). If a low level of employment was attained by a rather flexible labour law regulation, then it is a questionable strategy to create more jobs by more flexibility. It is not the aim of this paper to deeply analyse the debate on flexibilization of national labour laws in Europe, however, this issue had to be mentioned here due to its role in developments concerning the structure of employment forms. ← 24 | 25 →

Employment protection is relatively high in the euro area

Index scale from 0 (least restrictive) to 6 (most restrictive)

Source: Eurostat (online data code: Ifsi_emp_a)

In these post-socialist countries the Soviet tradition of a separate Labour Code, containing most of the rules on employment protection, is still flourishing. In my view, it is a beneficial legal heritage, since it makes labour legislation easier to apply, and at the same time more comprehensive. Thus, employment relationships are regulated by a Labour Code in all of these countries following the ‘Soviet model’. For that reason, employment law is, after 26 years in the market economy, still based almost exclusively on the regulation of the employment contract, with the exception of civil law contracts regulated by the Civil Code.

Thus, labour law reforms have been achieved either by several amendments of the Labour Code, or by the passing of a new codex. The former socialist Labour Code is still in force in three of these countries: the Czech Republic (1965)5, Poland (1974)6 and Bulgaria (1986)7. Certainly, these ‘old’ Labour Codes have been amended many times, so they hardly resemble the original, socialist texts. In the other eight Member States, the former socialist codexes have been replaced by new Labour Codes.

The first wave of these new codexes was passed before the first round of EU accessions in 2004. In the Baltic States the former Soviet Labour ← 25 | 26 → Code of 1972 was followed by a new law in Latvia8 and Lithuania9 in 2002, later in Estonia (2008)10. New Labour Codes were passed before EU accession also in Slovakia (2001)11, Slovenia (2002)12 and Romania (2003)13. Harmonization of the labour law directives had proven to be a good opportunity to rewrite the Labour Codes in these countries.

Hungary14 and Croatia15 are the exceptions to the above trend, as the new Labour Codes were passed in these two neighbouring countries as a response to the financial crisis (in Hungary in 2012 and in Croatia in 2014). Thus, these are the best recent examples of comprehensive labour reform in the region. Evidently, there have been some other proposals for new Labour Codes, for example the failed draft in Poland in 200616 and the just debated draft in Lithuania in 201617. Simultaneously, there have almost been as many amendments to the existing Labour Codes in the other countries as well in the last few years. On the whole, a new wave of labour law reforms has been initiated in a number of countries, which is generated by the political will to handle the new social and economic tensions, but above all to create more jobs. These reforms will ← 26 | 27 → be analysed below exclusively in respect of the employment forms and the legal structure of legal relationships aimed at work.

2. Promotion of atypical employment: is it really what we need?

Details

- Pages

- 506

- Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782807604179

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782807604186

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9782807604193

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782807604162

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11454

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (July)

- Published

- Bruxelles, Bern, Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2017. 506 pp., 12 b/w ill., 10 tables