Heritage, Cities and Sustainable Development

Interdisciplinary Approaches and International Case Studies

Summary

What does this imply for cities which have become global players ever increasing in size, flux, power and complexity? How can heritage and development be mutually reinforcing? How can policies and practices of heritage be fruitfully integrated as a resource into wider urban change while respecting environmental, social and cultural concerns?

This volume analyses ways in which heritage recognition, conservation, valorisation and promotion have been integrated in urban planning and policies. It benefits from the cross-fertilization of specialists and practitioners in political, urban and area studies, cultural policy, sociology, anthropology, urban planning and architecture, who use a variety of methodologies to explore cities as living entities. The book examines the disputed influence of international frameworks, notably from UNESCO, and takes a holistic approach to cultural policies encompassing both theory and application, listed and unlisted sites, East and West. Case studies from Chile, China, Cuba, Ecuador, England, France and Peru allow to grasp both the diversity of situations and the converging policy and management practices. This volume’s global perspective on urban issues will be of interest to urban planners, cultural policy and heritage specialists, social and human sciences researchers and students.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- About the editor

- About the book

- Citability of the eBook

- Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Heritage, Cities and Sustainable Development. Challenges and Opportunities between Theory and Practice

- Part I People-Centred Built Heritage Conservation

- Chapter 2 Industrial Heritage and Urban Landscapes: Prospects for Sustainable Development in English Cities

- Chapter 3 Turning private causes into common cause? The role of sponsorship in preserving vernacular heritage sites in France1

- Part II Challenges in Historic Urban Landscape Policies

- Chapter 4 The Master Plan for the integral rehabilitation of Historic Havana: what consequences for the urban environment, what impacts on the population?1

- Chapter 5 Valparaíso, the Pearl of the Pacific: the power of artistic imagination on a touristic world heritage city1

- Part III Inclusive Approaches to Urban Heritage and Planning

- Chapter 6 Implementing the Historic Urban Landscape Approach: Exploring Participatory Planning in China1

- Chapter 7 Quito: when local consultation redefines heritage and planning

- Chapter 8 Lima: Open City. A Pedestrian Urban Regeneration Strategy for the Historic Centre of Lima

- Chapter 9 Concluding Remarks. Comparative Visions of Heritage — Holistic Visions of Heritage?

- Afterword

- Authors’ biographies and summaries

- Index

Francesco Bandarin

Director, World Heritage Center of UNESCO (2000–2010) and Assistant Director-General of UNESCO for Culture (2010–2018)

In November 2011, the General Conference of UNESCO adopted a new normative text, the Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. This is the first UNESCO Recommendation on Historic Cities after the 1976 Nairobi Recommendation concerning the Safeguarding of Historic and Traditional Settlements and their Role in Contemporary Life. Eight years after the adoption of the new Recommendation, it is time to look at the first results of its implementation.

This book is a contribution to the analysis and reflection that is going on today at UNESCO and in several research and urban heritage management circles. Urban conservation, a practice defined at the end of the nineteenth century and included in the practice of urban planning in the mid-twentieth century, today plays an important role in the world of cultural heritage. Indeed, if we limit our attention to the World Heritage List, urban heritage now appears as one of the most important, if not the most important, of all heritage categories. Urban conservation gained an important dimension in the second half of the twentieth century, first in Europe, then in many other regional contexts, when the concept was gradually introduced into legislation and urban planning practices.

Ultimately, we can say that today’s historic cities are better preserved, protected, managed in national and local contexts than in the past, but have lost many of their traditional functions. No doubt, the strength of the markets has largely overcome the original intentions of planners ←9 | 10→and politicians and today the historic cities are under intense pressure of transformation, because of new phenomena, such as gentrification or tourist use.

In this complex and contradictory situation, several reasons have supported the need to revise the current paradigm of urban conservation. It is within the framework of the World Heritage Convention that this reflection was launched, starting in 2003. Since historic cities now represent the majority of sites inscribed on the World Heritage List, the World Heritage Committee increasingly realized the need to redefine the approach to urban conservation.

That is why, at UNESCO’s request, a conference was organised in Vienna in May 2005 to discuss how to consider contemporary transformations in historic areas, in a manner consistent with the preservation of their heritage values. It published a document, the Vienna “Memorandum” on World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture, which proposed the concept of historic urban landscape as a tool for reinterpreting urban heritage values and stressed the need to identify new approaches and tools for urban conservation. The Memorandum was welcomed by the World Heritage Committee at its 2005 session, and formed the basis of the Declaration on the Conservation of Historic Urban Landscapes, adopted by the 15th General Assembly of States Parties to the World Heritage Convention in 2005. It is on the basis of these acts that the drafting of the Historic Urban Landscape Recommendation was initiated.

The interest of the international community for intangible heritage has also increased in recent years, and has led to the adoption, by UNESCO’s General Conference in 2003, of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, an important addition to all normative instruments for safeguarding heritage. The new Convention, beyond its conceptual contributions, supports the need to recognize the multiple layers of identity and other intangible aspects associated with cultural landscapes.

Finally, the importance of cultural diversity in the definition of heritage values was reaffirmed with the adoption of the Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions in 2005.

Without a doubt, the modern practices on which urban conservation is based suffer from their derivation from the principles of monument ←10 | 11→conservation. In the 1964 Venice Charter, the founding document of modern conservation, the focus is almost exclusively on the monument and its restoration. In fact, it was this limitation that prompted ICOMOS to formulate a specific complementary charter for urban conservation in 1987, the Washington Charter, a document that substantially enriches the international toolbox in this area.

The Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape reflects all these achievements and the new approaches proposed by the Conventions adopted in the first decade of the new century. In practice, elements already present in the various existing normative texts have been brought together and put to system, such as the valorization of the different historical layers, the interest for the relation with the natural environment of the cities, their geology and ecology, the importance attributed to intangible values and contemporary creativity in historic areas, and finally the role of the social and economic dimension in the conservation of the city.

It should be noted that the historic urban landscape is not a new “category” of heritage. On the contrary, the proposed approach recognizes the importance of the tradition of conservation of historic cities: it rather aims to promote an integrated view of the city, a modality of change management that can face the new challenges of conservation of the historic cities. A Recommendation is not comparable to a legislative text: it is rather an orientation that must be implemented and adapted to the different local frameworks. The Recommendation identified the four areas that require in-depth and specific context work for effective implementation: (a) tools for civic participation; (b) knowledge and planning tools; (c) regulatory systems; d) financial tools.

In all these areas, a great deal of research has been launched in the different regions of the world, with encouraging results, which will be examined by the General Conference of UNESCO in 2019.

In this sense, the work presented in this publication is a contribution to a body of research and management practices that has developed in all regions of the world, particularly in Asia and Latin America. The main issues that contemporary transformations raise in the field of urban heritage conservation and the challenges that lie ahead are well framed by the contributions: the question of civic participation, the problem of tourism, the use of public spaces, valuing heritage in the context of sustainable development.

←11 | 12→All this clearly shows that a Recommendation cannot be conceived as an isolated object. All the themes addressed by this publication, and in a broader sense by all the research in progress, can today refer to a unitary framework, following the adoption of the New Urban Agenda by the HABITAT III Conference in 2016. At this Conference, UNESCO presented the CULTURE: URBAN FUTURE Report, which proposes models for integrating cultural and heritage dimensions into sustainable urban development policies.

It is in this important frame of reference that the Historic Urban Landscape Recommendation, and indeed all efforts to conserve urban heritage, will find their points of reference in the years to come.

Cécile Doustaly

Agora, University of Cergy-Pontoise

“Heritage is a key resource to make cities and human settlements

more inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.”

(UNESCO, Historic Urban Landscape Recommendation, 2011)

In the last decades, urban development and heritage paradigms have shifted greatly. Worldwide destructions of heritage have brought to light its social and economic role for societies. This volume analyses how the latter have intersected, leading to a growing call for sustainability. This broad approach understands heritage policies, conservation and management as local, national and global issues which reflect the strain between idealism and pragmatism, theory and practice.

Due to faster urbanisation and population growth, human settlements have faced an array of swift changes, with half of the world population now living in urban areas (as opposed to 15 % in 1900). Since the 1980s, cities have become global players ever increasing in size, flux, power and complexity. New forms of capitalism mean a multiplicity of public, private and voluntary actors are involved in this new model of multileveled polycentric governance based on transnational networks. ←13 | 14→As new strategic platforms competing for change, cities supported the rebirth of urban centres and the development of culture and tourism, central to their identities, attractivity and development. However, they have faced increasing economic, social and spatial inequalities. In the Western world, this was exacerbated by reduced public budgets following the 2008 crisis. In emerging countries, booming cities have led to uneven economic growth and hardships, posing major threats to urban conservation, such as slums, lack of infrastructure, environmental issues. Holistic and progressive forms of governance are explored worldwide to prioritise “human and planetary flourishing”1.

In the same period, the heritage field has gone through a democratisation process in terms of values, assets, producers and publics, allowing more cultures and communities to gain recognition. Through this process, cultural heritage, traditionally equated with national identity, has also become a strong vessel for territorial and global imaginaries. Growing interest and concern have been raised for urban heritage, approached broadly as “urbanity”, favouring “the values of the city, [more] than the city itself”2. The acceleration of the new global urban era has been associated with theoretical and practical challenges and more sustainable models of urban heritage production and consumption are being called for East and West.

The concept of sustainable development has emerged as the main foundation for current international cooperation frameworks. The reference text defines it as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” and resting on three pillars: environmental protection, economic growth and social equity. While natural heritage was associated to environmental sustainability, cultural heritage and landscapes were tied to social development and the preservation of community values. It is only recently that heritage has been approached in policy circles as a non-renewable resource deserving protection, UNESCO playing a major part in culture being integrated in sustainability frameworks3.

←14 | 15→Shifting attitudes to the link between heritage and development can be identified. Initially, development was judged a threat to heritage as stated emphatically in UNESCO’s World Heritage (WH) convention: “the cultural heritage and the natural heritage are increasingly threatened with destruction not only by the traditional causes of decay, but also by changing social and economic conditions which aggravate the situation with even more formidable phenomena of damage and destruction”. The Convention only quoted tourism and development once, to warn against the dangers of “large-scale public or private projects or rapid urban or tourist development projects” and did not refer to their potential social and economic benefits. Conversely, especially in cities, the heritage conservation called for by UNESCO was seen as a hindrance to economic, social and urban development4. In a second phase, urban heritage came to be considered as a resource for socio-economic development, allowing for poverty alleviation in many parts of the world. Only the negative impacts of development were treated as a threat, notably for properties included in the WH list whose prestige, visitors and revenues increased rapidly. Chapters in this volume illustrate how such developments were often carried out with insufficient consideration for long term impacts.

Can heritage and development be reconciled through a new sustainable paradigm? What are the avenues to provide the conditions for local inhabitants to preserve their traditional environments while retaining cities open to visitors and economic development? What methodologies can encourage commonality between conflicting values, discourses and practices?

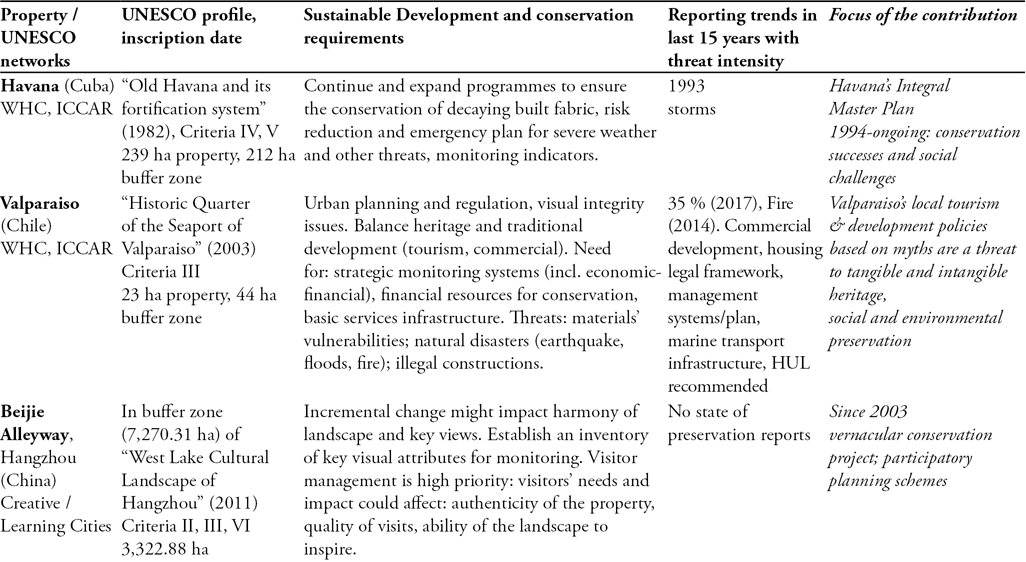

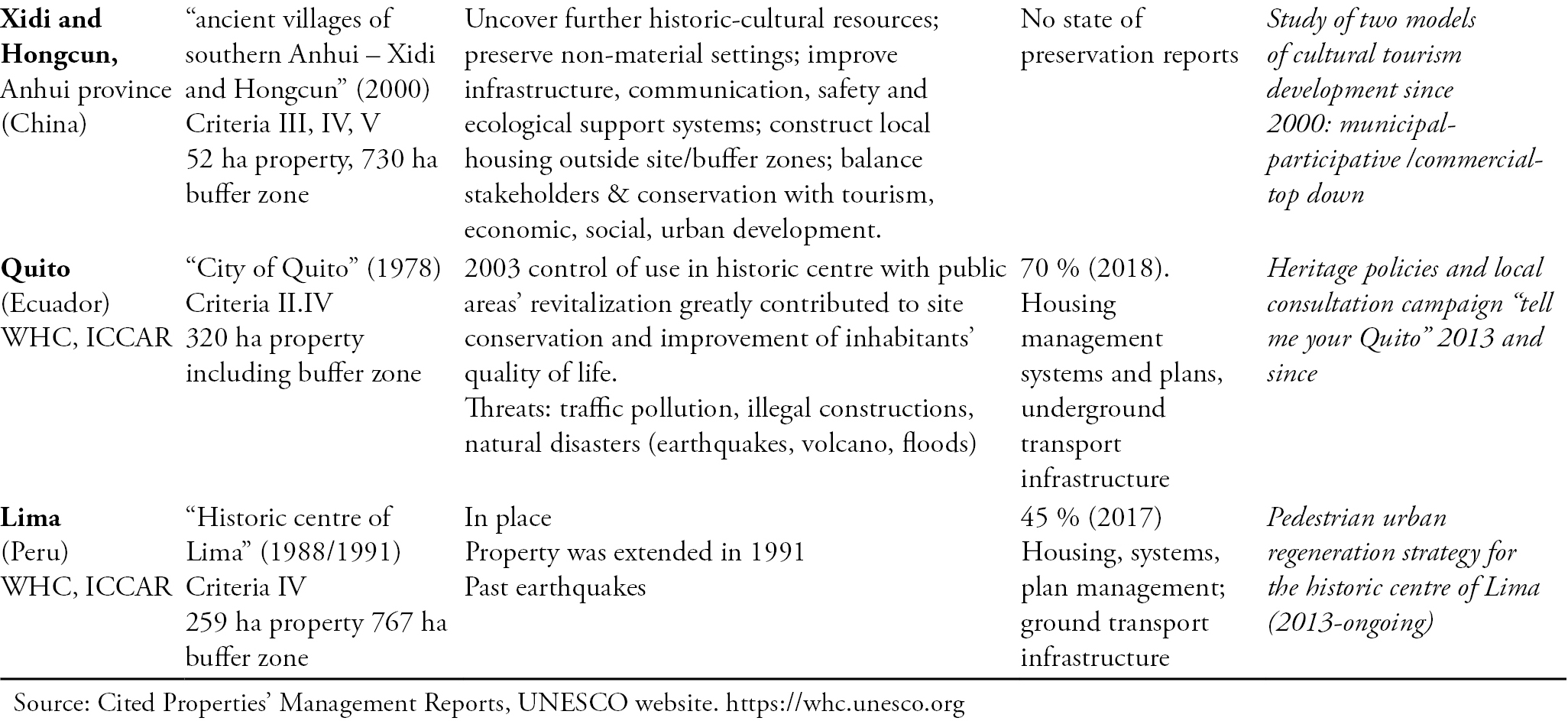

To answer these questions, this volume provides international comparisons of urban heritage policies that often considered heritage both as a threat and a resource for development, illustrating why cultural components are increasingly considered a pre-requisite to devise sustainable urban planning and policies. If global issues in the field and converging practices can be identified, specific national and local challenges also need to be studied and addressed. The contextualized case studies provide a complement to existing literature by focusing on ←15 | 16→long-term evolutions in relation to the international framework. They bring together inputs from sociology, anthropology, political, urban and area studies, cultural policy, planning and architecture. In taking a holistic approach encompassing both theory and application across a variety of disciplines, they consider where methodological pitfalls lay and how sustainable policies might be successfully implemented in contemporary cities and settlements around the globe: from China, to Cuba, Chile, Ecuador, France, the United Kingdom and Peru. Case studies intentionally tackle both WH inhabited historic towns (included in the WH list from 1978 to 2003), buffer zones and other types of urban landscapes such as villages and unlisted sites (see table 2 below).

Table 2. Profile of properties included in world heritage UNESCO list or buffer zone discussed in this volume. WHC (World Heritage & Cities); ICCAR (International Coalition of Inclusive and Sustainable Cities)

Details

- Pages

- 258

- Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782807611283

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782807611290

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9782807611306

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782807611108

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16338

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (January)

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 258 pp., 23 fig. col., 4 fig. b/w, 2 tables, 4 graphs.