«My Name is Freida Sima»

The American-Jewish Women’s Immigrant Experience Through the Eyes of a Young Girl from the Bukovina

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

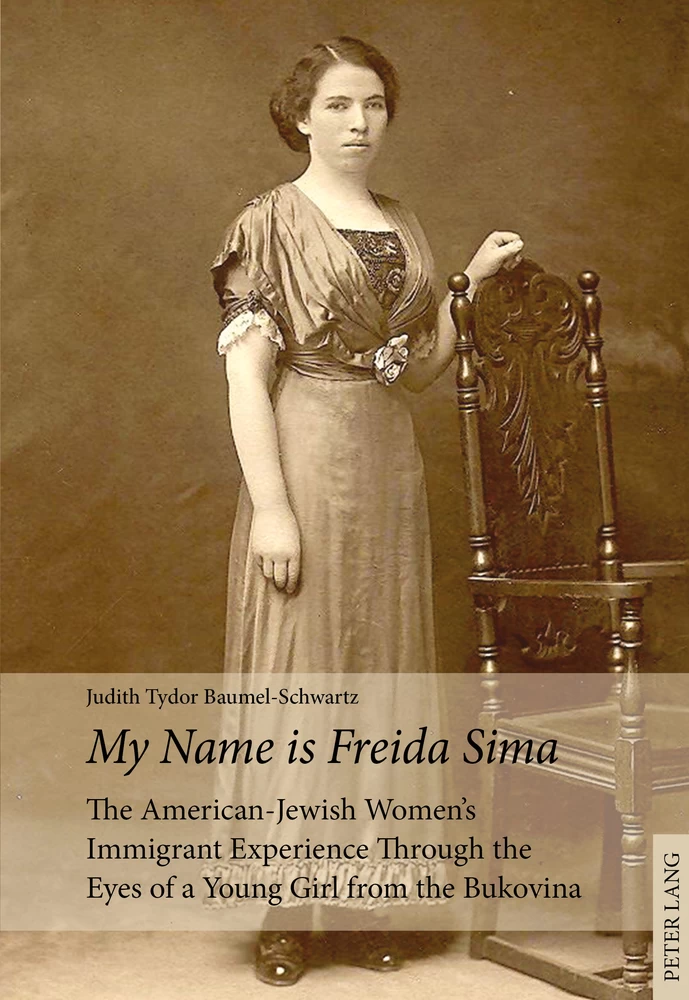

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Chapter 1 How it all began – Ramat Gan 1975

- Chapter 2 The Education of Freida Sima – Mihowa-Eastern Galicia (1895–1911)

- Chapter 3 The Immigration of Freida Sima – New York (1911–1923)

- Chapter 4 The Courtship of Freida Sima – New York (1923–1928)

- Chapter 5 Marriage, Motherhood, and Money: Freida Sima and the Great Depression – New York (1929–1939)

- Chapter 6 Freida Sima and the Holocaust – New York, Rumania, and Transnistria (1939–1945)

- Chapter 7 New Beginnings: Freida Sima and her Reunited Family – New York and Israel (1945–1953)

- Chapter 8 Brighton Beach Memoirs: Freida Sima, Max and the Golden Years (1954–1974)

- Chapter 9 Freida Sima Makes Aliyah – Ramat-Gan and New York (1974–1984)

- Chapter 10 An End that is also a Beginning

- Maps

- Family tree

- Glossary of Non-English Words

- Bibliography

- Photographs

- Index names

- Index places

- Index organizations, institutions, issues

Chapter 1 How it all began – Ramat Gan 1975

Introduction

It had truly been a joyous evening. For hours, the entire family sat around the dining room table, eating and celebrating. An unending array of food had streamed out of the kitchen: strips of lightly fried schnitzel, paper-thin potato pancakes with apple sauce and finally, more substantial fare, meat patties smothered in fried onions. Throughout the evening, platters of delicacies were passed around, especially the apple-matzo meal latkes that were my grandmother’s specialty. “Come sit down Ma”, my mother called out to her, still in the kitchen, “it’s your day, enough cooking.” “Just one more batch”, was the expected answer. Although it was still two months until Chanukah, these latkes had nothing to do with the season. In my grandmother’s family, apple pancakes were a tradition, and no celebration was held without them.

And what a celebration it was! Not only was it my grandmother’s eightieth birthday, but it was also one of those rare occasions when a good part of her extended family could gather under one roof. Of course it wasn’t her entire family; four of her siblings lived in New York and her four stepsons lived in California, ten time zones away. But she was with her daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter, with whom she had moved to Israel a year earlier. “Another move across the sea”, she had said, musing over how much had changed since her first overseas journey, sixty-four years ago. Then, she had been a young girl of fifteen who had left home alone to get an education in America. Now she was a very senior citizen, but her sense of adventure remained undiminished. “Who knows what this journey will lead to? Be positive!” she admonished me, when I, at fifteen, had expressed uncertainty coping in a new country.

The crowd at the table included some of my grandmother’s brothers and sisters-in-law who had gathered for the occasion: her oldest brother Abie and his wife Minnie, who were in Israel on a visit from America, and two middle brothers, Srul and Leibish, along with their wives, Anna and Frieda. She still thought of Srul and Leibish as “the boys” as they had been five and three when she had left Europe. The next time she saw them, ← 7 | 8 → they were already in their mid-forties, having been separated from her by three geographical upheavals, two World Wars and one Holocaust which they had experienced in Europe while she was already in the United States. Now they were in their late sixties, and she was trying to bridge the gap of years and experiences which separated them. Above all, she had to remember not to pepper her Yiddish with English expressions which they, having come directly to Israel from post-war Europe, could barely understand.

“Time for cake and presents”, I called out, as I brought in a round birthday cake ablaze with candles. By the time my own mother would celebrate her eightieth birthday more than three decades later, we would be using a large sheet cake onto which we could easily fit the requisite eighty candles. Then, however, Israeli stove pans were smaller. Looking at the size of the cake earlier in the day, my mother and I had wordlessly decided to stop at eighteen candles – the numerical equivalent of the Hebrew word chai – “life”. One by one those sitting around the table presented my grandmother with birthday gifts: a scarf, a bottle of cologne, a book of Yiddish poetry, a sweater, a pair of warm slippers, a rhinestone pin, and finally, a curiously shaped package which appeared to be some kind of large square glass bottle.

“How many einiklach (grandchildren) give their Baba apricots in liquor for her eightieth birthday?!” she laughed as she handed out tiny glasses into which she poured the spirits. “This is what you give the woman who has everything!” Each of the guests lifted a small tumbler containing some of the clear liquid, raising the glass and calling out lechaim – to life. “Boytee, you have some granddaughter”, said Abie. “And she has some grandmother!” my grandmother answered back. “Shvester (sister) Babaleh, is this how they raise them in America?” asked Srul, using her childhood nickname, and shaking his head at the notion that a sixteen-year-old girl would give her octogenarian grandmother a bottle of schnapps for her birthday. “Why not? It tastes good”, she answered him, shrugging her shoulders and looking towards me in the kitchen doorway. “Lechaim” she called out with a smile, raising her glass high and blowing me a kiss.

Towards midnight, the crowd began to take their leave from the “birthday girl”, giving her final blessings for a long and healthy life. “So Ma, how did you enjoy your party?” my mother asked, after closing the door behind the last guest. “It was wonderful”, my grandmother answered in her customary tongue-in-cheek manner. “The best eightieth birthday party I ever had.” “Just wait until you are ninety,” I countered, “then we’ll even top this ← 8 | 9 → one.” Little did I know that she would be gone a year and four months short of her ninetieth birthday.

“Just explain one thing Baba,” I asked her in a more serious vein. “Why do your brothers in America call you by one name, while your brothers in Israel call you by another?” “And why do my older cousins in Israel call me by a third?” she replied, “It’s a long story and it’s the story of my life, the places that I have lived and the people that I have known. Everyone gives you a different name,” she said, “but the only important thing is the name that you eventually give yourself. That’s the one that people remember.”

Who was Freida Sima?

My grandmother was a woman of many names and many talents, each of which corresponded with a different period in her life. Like numerous women of her generation. she was able to whip up a three course meal out of nothing, and make a one week Depression salary last for six months. But she could also milk a cow with her eyes closed and ride a horse bareback, legacies of her childhood on an Eastern European farm, in one of the few areas where Jews were permitted to own land by 1860. Used to living creatures of all kinds, she was fearless, picking up live cockroaches and throwing them out the window, laughing when I would shudder to see her holding them with her bare hands.

Although she only became a mother when she was thirty-three, she became “Baba”, meaning grandmother, when she was less than a year old. As her granddaughter I called her “Baba”, but she had first been called that more than sixty years before my birth. This was how her older cousins referred to her, treating it as a nickname and calling her “Babaleh” in diminutive. On her immigration papers from 1911 she is listed as Babe, the immigration official’s phonetic equivalent of what he heard when he asked her name, and she automatically answered what everyone had called her for the previous fifteen years, “Babeh”.

The story of how she received that nickname was a central tale in our family lore. When her parents married, her mother Devorah had long fiery-red braids that almost reached the ground. Enamored with his young wife’s hair, her husband Nachman forbade her to cut it after marriage, as was the ← 9 | 10 → custom. Instead, she pinned up her flowing locks under her marriage wig, to the dismay of her relatives and neighbors who had come to shave her head the morning after her wedding. What’s more, it appears that she used to pull out pieces of her own beautiful hair from under the wig and wrap it around her head to make the wig look more lifelike. Nachman was obviously happy with the results and so, one presumes, was seventeen-year-old Devorah, but the same was not true for the women of Mihowa, as we will soon see. Refusing to heed their warnings about where such immodesty could lead, she and her tall, strapping Nachman lived happily together, soon delighting in the news that she was going to bear their first child.

Soon after, my grandmother entered the world and was named Freida Sima. Sima after a neighbor who had recently died childless, and Freida, the Yiddish equivalent of Simcha – “happiness” in Hebrew, in honor of Simchat Torah, one of Judaism’s most joyous festivals which was celebrated on the previous day. But that happiness was soon threatened. Several months later little Freida Sima fell ill with diphtheria. Seeing her baby convulsed with fever, the terrified eighteen-year-old Devorah ran to a neighbor for assistance.

This was the moment that the local women had waited for. Admonishing Devorah that her baby daughter’s illness was the Lord’s punishment for her misdeeds, they coerced her into shaving her head in the hope of appeasing the Almighty. When Nachman returned home and saw his wife’s denuded scalp, he bellowed with rage, running out of their cottage, and swinging an axe at anyone and everything in sight. But it was too late. The deed had been done, and Devorah never grew her beautiful hair again.

At the same time, in order to “cheat the devil” it was customary to change a sick child’s name to that of an elderly person, so that they would be spared the evil eye. Boys would often receive the name Alter (“The old one”) or Zeide (grandfather), and girls would be called “old lady” or grandmother. Thus, little Freida Sima was re-named “Baba”, or “Babaleh”, “little grandmother”, a name which stuck for close to ninety years, almost wiping out the memory of what she had been called at birth. All of her future names would be based on the sound of this one. Her aunts in America gave her the English name “Bertha”, which was the closest one they could find to “Babaleh”. After joining her in America, her younger siblings transposed it to “Boytee” which was easier for them to pronounce. A decade later, Max, her Russian-born husband, would call her “Bert” or “Bertie”, glossing over the “th” sound which was so difficult for immigrants to enunciate. Maybe that was why my grandmother was always careful to stress the “th” in “the”, ← 10 | 11 → pronouncing it with a pure American accent, and not slurring it, as did so many of the people in New York, her adopted city.

Only when old age began creeping up on her did she begin to refer to her birth name, reminding us of its existence. At her eightieth birthday party, after everyone had toasted her with good health and long life, she turned to my mother and said “Just remember one thing. My name is Freida Sima. That’s what I want you to put on my tombstone. Remember. Freida Sima”, she repeated a second time.

One of my grandmother’s favorite expressions was “I was Jewish before you were born”, and indeed her almost automatic reactions to various situations were deeply rooted in Jewish traditions, customs, beliefs, and even superstitions. Happiness is transient, an illusion. Every moment of joy has its flip side lurking in the shadows. Traditionally, Jews dilute even the greatest happiness with a brief mention of sorrow. Ashes are placed on a bridegroom’s forehead; a glass is broken during the wedding ceremony, in memory of the destruction of the Temple. Here too, there could be no absolute celebration or undiluted joy. Even when drinking a birthday lechayim and celebrating life, in a corner of your mind, you should always think of the grave.

Freida Sima and the Immigrant Generation

Our Sages have taught us that every person has a number of names: the one that parents give, the one that people use, and the one a person earns by themself, through their unique talents and abilities. That name, as my grandmother used to say, echoing the Midrash, is the most important name of all.1 Each name expresses a different one of a person’s attributes. Each contributes an essential component to that person’s essence. My grandmother was indeed a woman of many talents, and almost as many names; obviously her essence was just as complex.

Unlike many of my friends who had lost all their grandparents in the Holocaust, I was lucky enough to have one set of live grandparents who lived with us throughout most of my formative years. Both of my ← 11 | 12 → grandparents, Freida Sima (Bertha) Eisenberg Kraus and Max Kraus, were among the two million Jewish men, women and children who emigrated from Europe to the United States during the Great Wave of Immigration (1881–1914). From as early as I could remember, my grandmother would tell me stories about her life as in Europe, and her experiences as a young girl in America. She was a walking history book. From her I learned about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of March 1911 that occurred seven weeks after she arrived in New York, the largest industrial disaster in the city’s history, in which 146 garment workers, mostly young immigrants, died from the fire or jumped to their death. The fire was the impetus for the creation of the American Society of Safety Engineers, the oldest and largest professional safety organization in the United States.

Then, there was the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, or the funeral of the famous Jewish author, Sholem Aleichem, in 1916, one of the largest funerals in New York City history, where she joined the estimated 100,000 mourners lining the streets, including my grandfather, who she would only meet twelve years later. At a time when Harlem was an Afro-American or Hispanic neighborhood, she spoke to me nostalgically about the days when Harlem had been Jewish, her first real home, two weeks after getting off the boat from Europe.

In many respects, her story was representative of an entire generation of young women who came to America during those years. Like so many of them, she eventually worked in a sweatshop, which she always referred to as “the factory”. Not having a bathtub at her disposal, once a week she availed herself of the New York Public Baths, usually late on a Friday afternoon. During the 1920s, she and her cousins, also immigrants, imitated the “flappers” by wearing shorter skirts than the older generation, and bobbing their hair. Few, however dared to emulate those bold women in more than fashion.

During the years that followed, she, like so many young immigrants at that time, became exceedingly patriotic, viewing America as her true homeland. One of the proudest moments of her life was the day she received her Certificate of Naturalization, officially marking her status as an American citizen. Like so many of those immigrants who perceived America as the country that saved them from poverty, persecution or worse, her love of the United States was a lifelong affair that never underwent any disillusion. Her story was not only that of a generation of immigrant women, but it was also the story of America of that generation, the period to which American immigration historian Oscar Handlin referred when he wrote: ← 12 | 13 → “Once I thought to write a history of the immigrants in America. Then I discovered that the immigrants were American history”.2

In certain ways, however, her story was unique. Her initial reasons for immigrating were somewhat different than the norm, as were a number of personal choices that she made during her formative years in America. She married at what was then considered to be a rather advanced age for a woman from a traditional background. And in view of that background, her choice of spouse was also somewhat extraordinary, as were the circumstances leading to her sudden marriage. While she may have stretched the limits of propriety in her youth, she never once crossed over into territory that would have marked her as an overt rebel. My grandmother was the embodiment of a generation of young women immigrants who lived in a different world than their parents, not just figuratively, but in many cases, such as hers, also literally. Her story is certainly hers, but in some ways, it is also theirs, a micro-history that allows us a glimpse into the lives and inner worlds of an entire generation.

The Challenges of Micro History and Grandmothers

What can we learn from the story of a particular person or a family that can shed light upon the history of an entire generation? While preparing some of the articles upon which this book was based, I discussed that concept with a number of cousins, one of whom succinctly summed it up by stating: “There is really nothing illustrious about our family; they were little people in the large scheme of things, and this kind of micro-history shows the importance of even those who did not do earth-shattering things. They represent a large swath of humankind. And they certainly made a difference in the lives of their families and in the lives of future generations.”3

Even while conceptualizing the idea of this book, I grappled with the issue of how to best write a micro-history. For an experienced historian, writing a micro-history is a fascinating challenge, requiring one to walk a fine line ← 13 | 14 → between the individual tale being told and the broader narrative of a society at large. Throughout the process of creating this book I tried to remain aware of the various methodological pitfalls of dealing with micro-history of this sort, particularly the fear of trivialization which turns a historical enquiry into a series of anecdotes without a broader conceptual basis. Carlo Ginzburg, one of the world’s foremost micro-historians, reminds us that to write a successful micro-history, one should constantly switch back and forth between macro and micro components, first presenting the “text” within the “context” and then switching to the influence of the “context” upon the “text”.4 I have tried to do so by going back and forth between examining Freida Sima’s life as part of a broader story of mass Jewish immigration from Europe to the United States at the beginning of the 20th century, and then examining how what was going on in the broader story affected the individual, in other words, Freida Sima.

A second methodological issue concerns micro-history being a form of cultural history. A historian of cultural history deals with a number of historical discourses that require different tools and methodologies: intellectual history and its discourse, popular history and its discourse, daily life of various subgroups and the like.5 Although this is a study of cultural history, I have also drawn heavily on studies of economics, education, linguistics, geography, social welfare, psychology and other fields, in order to better understand the world of the immigrants, their issues of identity, culture, belief and praxis.

As I began to make headway through the literature about women immigrants to the United States during the Great Wave of Immigration, I was fascinated to see how many of the authors began their books or articles with descriptions of their immigrant grandmothers. Elizabeth Ewen opens her study of Italian and Jewish women in the Lower East Side with a description of her Italian grandmother who had been a milliner when she came to America.6 Sydney Stahl Weinberg’s opening paragraph of her study of the World of Our Mothers, evokes the memory of her “slight, wrinkled ← 14 | 15 → bubbe’s” immigrant sense of Jewishness.7 It seems, therefore, that my choice to examine the history of an entire generation of Jewish immigrants in America through my grandmother’s story, is not unique.

Details

- Pages

- 370

- Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034324113

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034324120

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034324137

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034321938

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0343-2411-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (December)

- Keywords

- Immigration Israel Holocaust American Jewry Gender World War II Great Depression

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2016. 370 pp., 20 coloured ill., 35 b/w ill.