New Ways to Teach and Learn in China and Finland

Crossing Boundaries with Technology

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- What are New Ways to Teach and Learn in China and Finland? (Hannele Niemi / Jiyou Jia)

- PART 1. Students as knowledge and art creators in digital forums

- Using Smart Phones to improve the Classroom Instruction of University Students (Jiyou Jia)

- Student-driven knowledge creation through digital storytelling (Marianna Vivitsou / Veera Kallunki / Hannele Niemi / Johanna Penttilä / Vilhelmiina Harju)

- Beyond the Classroom: Future Music Education through Technology (Inkeri Ruokonen / Heikki Ruismäki)

- Faculty of Medicine as a mobile learning community (Eeva Pyörälä / Teemu Masalin / Heikki Hervonen)

- E-Schoolbag Use in Chinese Primary Schools: Teachers’ Perspectives (Fengkuang Chiang / Shuhan Jiang / Mingze Sun / Yana Jiang)

- An E-learning Project for Language Instruction in China (Baoping Li / Xiaoqing Li / Lulu Sun)

- A study on the online learning behaviors of secondary school students (Xiaomeng Wu)

- PART 2. Personalized learning support in digitalized era

- Finnish Digital Learning Support for Children with Learning Difficulties in Mathematics (Pirjo Aunio)

- Supporting Hospitalized Children’s Agency and Learning Through Digital Technologies and Media (Kristiina Kumpulainen / Tarja-Riitta Hurme)

- Game-based Inquiry Learning: Design and Application (Yu Jiang / Lu Zhang / Junjie Shang / Morris Siu Yung Jong)

- Supporting Personalized Learning via a Big Data & Learning Analytics Platform for Early Childhood Education (Daniel Chen / Lingping Zhao / Yuxi Zhao / Huan Nie / Lei Fu)

- PART 3. Digitalization in teaching and learning environments

- Teachers as Researchers: Current Trends and Hot Topics (Shelly Zong / Jingjing Jiang / Yizhou Fan)

- Promoting Meaningful Science Teaching and Learning Through ICT in the Finnish LUMA Ecosystem (Maija Aksela / Jenni Vartiainen / Maiju Tuomisto / Jaakko Turkka / Johannes Pernaa / Sakari Tolppanen)

- Designing the First Finnish MOOCs (Otto Seppälä / Juha Sorva / Arto Vihavainen)

- Learning Analytics (Ari Korhonen / Jari Multisilta)

- In Search of the future of Educational Challenges in the Chinese and Finnish Context (Jiyou Jia / Hannele Niemi)

- Authors

In 2014, the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China and the Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland signed the Learning Garden agreement with the intention to establish synergies among various projects and agents involved in Sino-Finnish education cooperation. The University of Helsinki has promoted cooperation with Chinese universities as one of its strategic aims. In late 2014, the mutual understanding between the University of Helsinki and Peking University was updated and signed, and in November 2015 the University of Helsinki and Beijing Normal University decided to establish the joint Sino-Finnish Learning Innovation Institute for cooperation in educational issues in both countries.

The editors and authors of this book want to thank the ministries of both countries for the important initiative and for their systematic cooperation. This book is a product of a research collaboration between Chinese and Finnish researchers, especially in the area of educational technology. During the last two years, researchers have held several joint symposiums and conferences in both Peking and Helsinki. It has been amazing how much we have learned from one another despite the vastly different scales of our two countries.

All authors are very grateful to their own universities for providing an opportunity for inspiring international collaboration. The Finnish researchers also want to thank the Finnish funding agencies, the National Agency for Technology and Innovations (Tekes) and the Academy of Finland, which have supported the development of educational technology in Finnish educational settings in recent years. The Tekes project Finnable 2020 at the University of Helsinki has been especially important to this book.

As editors we want to thank all authors for their constructive and fruitful cooperation. We would also like to extend our thanks to our research assistant Pauli Peräinen, who has been an excellent help in technical editorial work and in the communication between the researchers from both countries.

In addition, the Chinese authors also want to express their deepest thanks to Professor Hannele Niemi for her devotion to and persistence in the joint research and this book. She has borne the main responsibility for finding resources and editing this book for a wider international audience.

We hope that this book will encourage the active cooperation between China and Finland in the future.

In Helsinki and Peking, May 6, 2016 ← 7 | 8 →

University of Helsinki

Peking University

What are New Ways to Teach and Learn in China and Finland?

Current trends in the Chinese context

Computer technology has been utilized in Chinese education since the 1980s, with audio-visual technology having been utilized since the 1950s. The growing popularity of the Internet and wired or wireless phone communication technology from the 1990s onwards brought a wider concept of ICT (Information and Communication Technology), which was then introduced into China and Chinese education. The Chinese-English word ‘informatization’ was invented by Chinese scholars at the end of the twentieth century and indicates the application and integration of ICT into other disciplines. For example, educational informatization means the application of ICT into education and the integration of ICT into education.

In 2010, a national plan for educational reform and development was issued by the central government. This plan declared “ICT has a revolutionary impact on education” (MoE China, 2010). The national propaganda at this time demonstrated the government’s insistence on the high priority of ICT for educational reform and development. In 2012, the “Development Plan of Educational Informatization for the next decade (2011–2020)” was published by the Ministry of Education to concretize the policy and methods of promoting the application and integration of ICT into education (MoE China, 2012).

Since then, with the steady increase of government expenditure on education, vast investment from central and provincial governments has gone to the application of ICT in education. For example, in Beijing’s Digital Campus Program, founded in 2009, 10,000 typical and outstanding lectures from primary and middle school teachers were recorded and aired on wired TV channels and uploaded to the Internet as ‘on demand’ programs, which could be freely accessed by pupils and teachers. Meanwhile, 100 schools were selected as “Experimental Digital Schools” and were granted an investment of approximately 300,000 Euros ← 9 | 10 → to buy hardware such as notebooks, tablet computers, electronic whiteboards and educational software.

From May 23 to May 25, 2015, the UNESCO and the Chinese Ministry of Education jointly held the International Conference of Educational Informatization in the city Qingdao in Shandong Province (MoE China, 2015). Educational officials, researchers, principals and school teachers as well as ICT companies from more than 90 countries came together to explore an effective approach to the integration of ICT into education and to examine the increased popularity of ICT usage in education. In the congratulation letters, Chinese President Xi Jinping called for the construction of a digitalized education system based on the Internet for individual growth and life-long learning, the building of a learning community for every person for any time and any place, and the training of a large number of innovative talents. He also declared that educational informatization can help more schools, teachers and students to use excellent educational resources and enable billions of children to share quality education and change their own destiny with knowledge.

On March 16, 2016, the National People’s Congress (Chinese Parliament) voted and passed the “thirteenth five-year plan for national economic and social development”. This plan aimed to enhance the educational level of all people and to promote the modernization of education. The concrete approaches detailed in this plan include the development of online education and distance learning, the integration of all kinds of educational digital resources and their service for society as a whole, and the deep integration of ICT with teaching and learning (National People’s Congress China, 2016).

In addition to governmental investment, high enthusiasm and investment from the industrial and business sectors in form of venture capital have been extended to educational informatization, as investors hope to profit from related industries and businesses.

Though many schools have been equipped with the latest hardware and software, and teachers are required and encouraged to use ICT in their teaching, there are still many problems with ICT application in China. The chapters in this book written by Chinese researchers attempt to address those problems and to explore potential solutions. For our purposes, ‘technology’ refers to the use of tablet computers and smartphones in education, game-based learning, and online instructional platforms. Subjects dealt with include Chinese as a first language, English as a foreign language, mathematics and science education. The target students vary from kindergarten children, primary and middle school pupils to university students. The teachers’ attitude and concern toward ICT usage is also investigated in two chapters. ← 10 | 11 →

In Chapter 1, Jia presents his research on using smartphones to improve the classroom instruction of university students. He designed drills for the required vocabulary corresponding to the textbook. The students were allowed to use their own smartphones to do the drills for about ten minutes in the classroom every week. After one semester of quasi-experiment with an experiment class and a control class, the “drill students” had increased their score in vocabulary tests significantly, and decreased their distance in regular exam to the control class significantly. The performance improvement was caused by the immediate feedback function of the vocabulary drills implemented by the course management system and smartphones. This chapter shows that the increasingly popular smartphones can easily be blended into classroom teaching and learning of university students.

In Chapter 5, Chiang et al. introduce the survey and interview results of 34 teachers from 4 eSchoolbag pilot schools in Shenzhen, Guangdong Province, a developed metropolitan city near Hong Kong. They found that the teachers’ attitudes toward eSchoolbag changed from positive to negative after using it due to many reasons, including the lack of appropriate resources for classroom instruction, students becoming negatively distracted by useless functions, and the unpredictable positive effect of this technology on students’ learning performance mainly represented by examination scores.

In Chapter 6, Li et al. present a large-scale e-learning project to promote the Chinese and English language learning in primary and secondary schools which has been implemented by the institute of Modern Educational Technology of Beijing Normal University since 2000. ICT like personal computers, tablet computers and the Internet are used as cognitive cooperation and communication tools to help the students to learn and explore by themselves. From 2011 to 2014, 4218 students and 174 teachers participated in the project for three terms in total. Li et al. determined the number of Chinese characters the students’ recognized and the scores of both Chinese and English language ability tests. The statistical analysis has proved that the test group achieved a significantly better learning performance than the non-experiment students. The teaching and learning model coined in this project can be extended to more rural schools to decrease the gulf between them and their urban counterparts.

In Chapter 7, Wu analyzes the log file for a large online learning environment originally developed for 110,156 secondary school students and found 5936 students (about 5%) who took part in some online learning activities. Three distinct patterns exist among those online learners: active learning participants, socially active participants and lower participants. Comparison between genders shows no significant difference between the learning behaviors of boys and girls. However, ← 11 | 12 → comparison between grade groups indicates that 7th grade students tend to learn for longer periods of time than older students, and 7th and 8th grade students tend to participate in more social activities than 9th grade students. This chapter suggests that some measures are needed to encourage students to effectively use the large amount of online resources.

Chapter 10 discusses how, based on literature review and theory analysis, Zhang et al. designed a game-based inquiry-based learning model. Guided by that model, they developed the “Farmtasia” inquiry-based learning curriculum and completed an empirical study in a high school. The result shows that this game-based inquiry learning model helps to expand the advantages of educational games, and cultivates students’ inquiry learning abilities.

Chapter 11 shows how Chen designed an integrated learning analytics and personalized child development support framework for kindergarten kids. Within this framework the author hopes to fully use the emerging technologies from machine learning through big data to construct an intelligent, interactive and adaptive learning environment for kids in practical preschool education. An international company has adopted his model for preschool education in China.

In Chapter 12, Zong et al. analyze three Chinese MOOCs’ (Massive Open Online Course) data with text analysis, word frequency analysis and coding techniques. They found that mainland Chinese teachers generally care about six research questions or aspects in particular; students’ motivation, learning ability, differences between students, pedagogy of teaching, technology of teaching as well as effective and efficient teaching.

The above chapters seek to give the reader just a glimpse of ICT application and integration in China. Because of time constraints and the length limitation of this joint book project, these chapters certainly cannot illustrate the whole story of Chinese education and ICT in Chinese education. For example, one important component in the dynamic and complex educational system, the students’ parents, is not discussed in those chapters. Parents are very concerned about their children’s usage of new technologies in schools and universities. They are afraid of their kids’ addiction to online video games, the negative influence of unrelated and even harmful online content on their kids, and the eye strain caused by the small screens of tablet computers and smartphones.

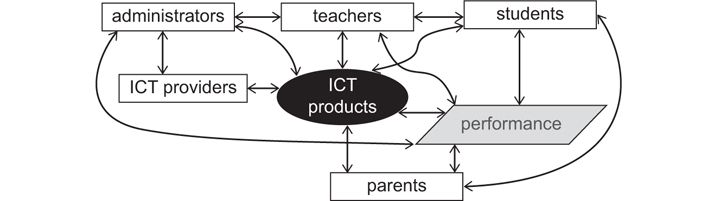

Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the dynamic and complex educational system regarding the ICT products applied in education. Educational authorities and school administrators, ICT providers, teachers, students and parents are all stakeholders in this giant system. They interweave with each other. ICT companies provide schools and students with educational ICT products, including hardware and software, with ← 12 | 13 → the allowance and appropriation from educational authorities and school administrators, and make profit from it. Teachers and students use the ICT products and can be influenced by them. In some cases, the parents pay for the ICT products. The students’ learning performance, as the outcome of the educational system, is paid special attention to by all stakeholders in the system: students, parents, teachers, administrators, etc. This model extends the understanding of an ICT-equipped educational system and emphasizes the efficiency of the system (Jia, 2014).

Figure 1: The dynamic and complex educational system

Current trends in the Finnish context

Finland, as a small country with 5.4 million inhabitants, needs all of its inhabitants’ talents and learning capacity. Since the late 1960s, the main objective of Finnish education policy has been to ensure that all citizens have equal opportunities to receive an education, regardless of age, domicile, financial situation, sex or native language. Education is considered to be one of the fundamental rights of all citizens (FNBE, 2011). Ensuring equal opportunities has had several consequences. Well-functioning educational structures and services are needed in order to enable people to use their opportunities in an equal manner. The main principle is that every school must be a good school and provide additional support to those learners who are at risk of dropping out. Learning to learn skills are emphasized at all educational levels and are seen as an important means to prevent exclusion (Niemi & Isopahkala-Bouret, 2012). Educational technology also has to be considered in this light. It is a tool for acquiring skills that people need in their lives; it helps one to grow in a knowledge-intensive society and in the middle of continuous changes.

Details

- Pages

- 334

- Year

- 2016

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631698730

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631698747

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631698754

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631676424

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-631-69873-0

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (April)

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, Warszawa, 2016. 334 pp.