Church and Civil Society in 21st Century Africa

Potentialities and Challenges Regarding Socio-Economic and Political Development with Particular Reference to Nigeria

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- 1. General Introduction

- 1.1. Motivation

- 1.2. Statement of the Problem

- 1.3. Current Status of the Research

- 1.4. Methodology

- 1.5. Delimitation

- 1.6. An Overview of Nigeria’s History

- 1.6.1. Nigeria before Independence

- 1.6.2. Nigeria since Independence October 1960

- 2. Civil Society

- 2.1. What Is Civil Society? A Broad View of the Concept

- 2.2. Historical Development

- 2.2.1. Classical Origins of the Term

- 2.2.1.1. Aristotle (384–322 BC)

- 2.2.1.2. Other Ancient Philosophers

- 2.2.1.3. Augustine (354–430 AD)

- 2.2.2. The Medieval Christian Era and Civil Society

- 2.2.2.1. Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274 AD)

- 2.2.2.2. Dante (1265–1321 AD) and Marsilius of Padua (c. 1275–c. 1342 AD)

- 2.2.2.3. Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679 AD)

- 2.2.3. The Modern Epoch

- 2.2.3.1. John Locke (1632–1704 AD) et al.

- 2.2.3.2. The French Revolution (August 1789) and G.F.W. Hegel (1770–1831 AD)

- 2.2.3.3. Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859 AD) et al.

- 2.2.4. The Contemporary View of Civil Society (20th–21st Centuries)

- 2.2.5. An Attempt at a General Definitional Summary of Civil Society

- 2.2.6. Conclusion

- 2.3. Civil Society in Africa in the Pre-Colonial Era

- 2.4. Civil Society and Its Current State in Contemporary Africa (21st Century)

- 2.4.1. The Achievements of Post-Colonial Civil Society Groups in Africa

- 2.4.1.1. Civil Society and Election Monitoring in Africa

- 2.4.1.2. Civic Education and Civic Engagement

- 2.4.2. Current Challenges and Problems Facing Civil Society on the Continent

- 2.5. The Situation of Civil Society in Nigeria

- 2.5.1. Elements of Civil Society Organization in Nigeria’s Pre-Colonial Period

- 2.5.1.1. Hausa/Fulani Pre-colonial Society

- 2.5.1.2. Yoruba Pre-colonial Society

- 2.5.1.3. Igbo Pre-colonial Society

- 2.5.2. Civil Society in Nigeria since Independence

- 2.5.2.1. Historical Retrospect

- 2.5.2.2. The Constitutional/Legal Framework for Civil Society Activism in Nigeria

- 2.6. General Summary of Chapter 2

- 3. The Church and the Social Question

- 3.1. The Nature of the Church

- 3.1.1. Etymology of the Word ‘Church’

- 3.1.2. Various Perspectives of Understanding the Church/the Church as Communion

- 3.1.3. The Divine-Human Nature of the Church with Regard to Practical Theology and Civil Society

- 3.2. The Nature of the Church’s Relationship to Civil Society

- 3.2.1. Is the Church Part of Civil Society?

- 3.2.2. Church and Civil Society in Europe and America in the 19th Century and Onwards

- 3.2.3. Church and Civil Society in Africa—Especially Nigeria—in the 19th and 20th Centuries

- 3.3. The Church’s Self-Understanding as Part of Civil Society

- 3.3.1. The Self-Understanding of the Catholic Church as Part of Civil Society

- 3.3.1.1. Pre-Vatican II Distance from Civil Society: The Church as Societas Perfecta

- 3.3.1.2. Post Vatican II Rapprochement towards Civil Society

- 3.3.2. The Self-Understanding of Other Christian Confessions as Part of Civil Society

- 3.3.2.1. The Churches in the USA and their Self-Understanding as Part of Civil Society

- 3.3.2.2. The Self-Understanding of the Churches in Europe Regarding Civil Society

- 3.3.3. The Position of Protestant Authors Regarding Civil Society

- 3.4. The Extent of the Church’s Involvement in Social Responsibilities

- 3.5. The Church’s Stand on the Socioeconomic and Political Order

- 3.5.1. The Principles of Catholic Social Teaching in Relation to Civil Society

- 3.5.1.1. The Principle of the Dignity of the Human Person

- 3.5.1.2. The Principle of Social Justice

- 1. The Principle of the Common Good

- 2. The Principle of Solidarity

- 3. The Principle of Subsidiarity

- 3.5.2. The Vatican II Council and the Popes’ Contributions on Civil Society

- 3.5.2.1. The Vatican II Council Documents on Civil Society

- 1. Gaudium et Spes and the Self-Identification of the Church as Part of the Society

- 2. The Civil Societal Responsibility of the Laity as seen in Apostolicam Actuositatem

- 3.5.2.2. Papal Contributions on the Church as Part of Civil Society

- 3.5.2.3. Holistic Development in Cooperation with Civil Society as the Basis for True Peace

- 3.5.2.4. Involving Civil Society in Addressing the African SocioPolitical Quagmire

- 3.6. Activities of the Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) in Relation to Civil Society

- 3.7. General Summary of Chapter 3

- 4. Towards Socioeconomic and Political Development: Critical Areas of Involvement within the Church and in Civil Society, through Caritas

- 4.1. Nigeria’s Sociopolitical and Economic Situation

- 4.1.1. Nigeria’s Sociocultural Order

- 4.1.2. The Sociopolitical Order

- 4.1.3. Nigeria’s Economic Situation

- 4.2. Caritas as a Necessary Approach of the Church’s Engagement with and in Civil Society

- 4.3. The Four Basic Areas of Approach to caritas Engagement by the Church

- 4.3.1. Human and Human-Related Services

- 4.3.2. Engendering Solidarity for the Poor and Needy

- 4.3.3. Sociopolitical Advocacy for the Rights of the Poor and Needy

- 4.3.4. Holistic Education for the Needy

- 4.4. Two Distinct Approaches to the Application of the Four Areas of caritas Engagement

- 4.5. The Four Main Areas of caritas Engagement Applied within the Church

- 4.5.1. Human Services and Other Service-Related Sectors

- 4.5.1.1. Healthcare Provision for the Sick

- 4.5.1.2. Care for Orphans and Vulnerable Children

- 4.5.1.3. Attending to the Aid of Persons Affected by Catastrophe

- 4.5.1.4. Prisoners’ Welfare and other Areas of Human-Related Services

- 4.5.2. Engendering Solidarity within the Church

- 4.5.3. Political Advocacy for the Poor and Needy

- 4.5.3.1. Political Advocacy for the Rights of Disabled Persons

- 4.5.3.2. Political Advocacy for the Rights of Prisoners

- 4.5.3.3. Political Advocacy for the Rights of Homeless Citizens

- 4.5.4. Holistic Education for the Needy

- 4.5.4.1. The Responsibility of Upholding the Socioethical Values of Society

- 4.5.4.2. Educational Opportunity for Vulnerable and Less Privileged Children

- 4.6. General Summary of Chapter 4

- 5. The Main Tasks of the Church (with its caritas) in its Engagement in Civil Society

- 5.1. Human and Human-Related Services

- 5.1.1. Economic Development through Initiatives and Programs Benefiting the Poor

- 5.1.1.1. Assistance to Micro-Businesses, Small-Scale and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)

- 5.1.1.2. Educational Training Approach towards Economic Empowerment

- 5.1.1.3. Partnership towards Requisite Manufacturing Infrastructure for the Poor

- 5.2. Engendering Solidarity with Civil Society Organizations

- 5.3. Political Advocacy for Issues of Social Justice

- 5.3.1. Church and Civil Society Groups: Influencing Good Governance

- 5.3.1.1. Advocacy for Economic Development through Budget Monitoring

- 5.3.1.2. The Southeast and Marginalization

- 5.3.1.3. Advocacy against the Niger Delta Environmental and Economic Problem

- 5.4. Holistic Education and Training for the Needy

- 5.4.1. Establishment of caritas-Research Institutes for Peace and Sociocultural Studies

- 5.4.2. Fostering the Education of the Almajiri (Name for street children)

- 5.5. General Summary of Chapter 5

- 6. Dialogue between Christianity and Islam as Two Major Stakeholders in Civil Society

- 6.1. Background to the Christian/Muslim Relations in Northern Nigeria

- 6.1.1. The Emergence of Islam and Christianity in Northern Nigeria

- 6.1.2. The Current State of Relations between Islam and Christianity in the North

- 6.2. Causes of the Tense Relationship between Muslims and Christians in the Country

- 6.3. Current Dialogue Initiatives between Christians and Muslims in Nigeria

- 6.3.1. Christian Denominations in Nigeria

- 6.3.1.1. The Protestant Churches

- 6.3.1.2. The Catholic Church

- 6.3.1.3. Muslim and other Dialogue Groups

- 6.4. Towards a Fruitful Dialogue between Christians and Muslims in Nigeria

- 6.4.1. The Dialogue of Life

- 6.4.2. The Dialogue of Action

- 6.4.3. The Dialogue of Theological Exchange

- 6.4.4. The Dialogue of Religious Experience

- 6.5. Applying the Caritas Structural Principles to General Social Dialogue Initiatives

- 6.5.1. The Four Structural Principles as a Dialogue Approach in the Muslim Communities

- 6.5.1.1. Human and Human-Related Services

- 6.5.1.2. Animating and Fostering Solidarity for Less Privileged Muslims

- 6.5.1.3. Sociopolitical Advocacy for the Poor

- 6.5.1.4. Educational and Training Opportunities for the Needy

- 6.5.2. Social Dialogue with the Ethnic-Nationalities and Regional Stakeholders

- 6.5.2.1. Attaining Sociocultural and Political Peace

- 6.5.2.2. Dialogue towards Greater Understanding and Solidarity among the Ethnic Cultures

- 6.5.2.3. Dialogue towards Attaining Greater National Integration

- 6.5.2.4. Dialogue towards Stronger Force against Corruption

- 6.6. General Summary of Chapter 6

- 7. Challenges and Obstacles to the Realization of the Goals of the Church and other Civil Society Organizations

- 7.1. Corruption in the Social and Political Life in Nigeria

- 7.1.1. Corruption Generally Defined

- 7.1.2. The Social-Psychological Root Causes of Corruption in Nigeria

- 7.1.3. Corruption among Nigerian Civil Society Organizations

- 7.1.4. The Negative Sociopsychological Effects of Corruption in Civil Society

- 7.2. Lack of Unity of Purpose among the Various Organizations

- 7.2.1. Hostile Confrontations between Ethnic and Religious Groups

- 7.2.2. Preoccupation with Individual Group Interests and Lack of Unity among Civil Organizations

- 7.3. Financial Over-Dependence on International Partner NGOs and Other Donors

- 7.4. Lack of Adequate Qualified Manpower among the Civil Society Organizations

- 7.5. General Summary of Chapter 7

- 8. General Conclusion: Towards the Realization of Effective Contributions to the Sociopolitical and Economic Development of Nigeria

- 8.1. Recommendations for the Resolution of Challenges facing the Development of the Country

- 8.1.1. Human and Human-Related Services

- 8.1.1.1. Care of the Vulnerable and Less-Privileged

- 8.1.1.2. Health Insurance Provision Needs

- 8.1.1.3. Cooperation with Government and Market Stakeholders for Economic Development

- 8.1.1.4. Socioeconomic Projects for the Poor and Needy

- 8.1.2. Necessity of Engendering Solidarity among Stakeholders

- 8.1.2.1. Solidarity Generation Method of the Caritas Organization

- 8.1.2.2. Solidarity for Peace and Unity as Basic Conditions for Development

- 8.1.2.3. Long Term Dialogue with Ethnic and Regional Stakeholders

- 8.1.2.4. Intercultural Integration Programs towards Improving National Cohesion

- 8.1.3. Political Advocacy for the Rights of the less Privileged

- 8.1.3.1. Necessity of the Campaign against Corruption

- 8.1.3.2. Political Advocacy for the Rights of “Settlers”

- 8.1.4. Teaching Responsibility of the Church and the Training of Qualified Personnel

- 8.1.4.1. The Socioethical Teaching Responsibility of the Church

- 8.1.4.2. Professional/Technical Training of Qualified Staff for Civil Societal Engagement

- 8.2. Prospects of an Effective Contribution to Nigeria’s Sociopolitical and Economic Development

- 8.2.1. Development of Human and Human-Related Services

- 8.2.2. Engendering Solidarity among Religious and Other Civil Stakeholders

- 8.2.2.1. The Exigency of Dialogue with the Religious and Civil Organizations

- 8.2.2.2. The Imperative of Mutual Acceptance and Relationship

- 8.2.3. Sociopolitical Advocacy for the Rights of the Less-Privileged: Tackling Corruption

- 8.2.4. The Holistic Educational and Teaching Responsibility of the Church

- 8.2.4.1. The Essentiality of the Socioethical Teaching Responsibility of the Church

- 8.2.4.2. The Consciousness of the Inalienable Nature of the Church as the Embodiment and Carrier of Christ’s Caritas

- Bibliography

A careful look at the achievements of various pre-colonial civil organizations1, and the groups of men and women of various nationalities that later became Nigeria and the gallant feats of many pro-independent organizations2 during the colonial epoch is very revealing. This is in addition to the brave fights of other civil groups during the era of military dictatorship in the country3. Records of the significant contributions they made towards the socioeconomic and political reshaping of the society in their time abound. In the light of the above observation, a question arises: Are there special things that these people did that cannot be replicated by their present-day Nigerian civil society counterparts? This is especially in view of the enormous socioeconomic and political challenges facing Nigeria and indeed other African countries today. Or are there greater obstacles today than before? Is there no way of overcoming these barriers so as to make the impact of the civil groups felt everywhere? In the same vein the question arises: is the Church part of civil society? If it is, should we expect its positive contribution towards the country’s sociopolitical and economic development? If there is any obstacle facing the socioeconomic upliftment of the society, it should be part of the responsibility of theological science to point it out and show ways of applying civil, human and material resources for the good of the society. In this regard, the attention of the student of caritas science is called for.

For this reason, this researcher makes a critical study of the potentialities and capacities as well as the challenges facing the Church and other civil society groups in Nigeria. Such a research will contribute to making their positive input to societal building richer and more relevant. ← 19 | 20 →

Civil society is a fundamental aspect of all nations of the world whose capacities and potentials are large because the government itself is taken from it.4 That implies that civil society must necessarily play a critical role in the social, political, economic as well as the overall development of each country. Hence it is essential to find out its contribution to the development of 21st century African countries, especially Nigeria. To this end there is the need to find out what counts as part of civil society and whether the Church also belongs to it.

To begin with, however, it is important to understand the connection between the Church and civil society. Hence the first question presents itself: what does one understand by the term “Church”? Does the Church have any connection to civil society? Or does the Church have anything to say about the social and economic conditions of the society? Furthermore, if there is any relationship between the Church and civil society, is there any theological basis for the civil societal engagement of the various church organizations?

Again, what does one understand by the term “civil society”? In addition, did civil society or related entities exist in pre-colonial Africa? In what ways did they exist? Still further: is there any possibility of and necessity for the cooperation between the Church and other civil groups for the good of the society at large? The latter question calls for investigation because civil society groups are usually free and independent from one another and often pursue divergent interests. However, it remains to be asked how the freedom of each one can be guaranteed if every one of them begins to pursue those self-interests without regard for the freedom of the others.5

There are many international nongovernmental organizations in Africa. Some of them are associations while others are foundations. Many of them have positively touched the lives of many African women and men in many ways and undertake many life saving measures for the good of the people. The fact that it is mostly international civil society organizations whose services are oriented towards the common good causes one to ask: Are African civil society organizations not yet conscious of the problems facing them? Or is it that they do not have the capacities or the resources to tackle them? This is especially cogent when viewed against the backdrop of what similar organisations achieved in the ← 20 | 21 → colonial and early post-independence era. Could it be that they do not want to have anything to do with the problems facing them? For example, it is difficult to explain why it is only international nongovernmental organizations that draw attention to the injustices being carried out in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria, where oil companies engage in land, sea, and air pollution on a regular basis, with oil spillage and gas flaring. Hence it is pertinent to ask: What capacities (or options) exist for the individual civil societal groups in Africa, especially in Nigeria? What contributions can they make for the further development of their own society? Is it possible and can one hope for a big positive contribution coming from these civil society groups so as to effect the much-desired socioeconomic and political turn around in various African countries? What particular and crucial challenges militate against the realization of these goals and how can these be effectively tackled? It is obvious that many African countries are in the hands of bad regimes. Can these civil society groups assert themselves so as to bring about a change? These and many other questions are what this research will tackle and critically examine. This will be done especially from the background of what the caritas of the Church and many other civil societal organizations did in Europe in the past centuries.

1.3. Current Status of the Research

Experts and researchers have written much on the issue of civil society and its activities in various aspects of Nigeria’s sociopolitical life and development as well as in its public sphere in general. It is, however, to be noted that no one has specifically focused on the issue of the Church/civil society engagement and cooperation as a force for the sociopolitical and economic development of the country. Perhaps this may not be unconnected with the earlier doubts by some scholars as to whether the Church or religion belongs to civil society.6 Nigerian authors could have been misled into thinking that religion does not have any role to play as part of civil society because of the previous one-sided view of the former as an ‘other-worldly’ organization that has nothing to do with the things of the here and now. Thus, most literary efforts at exploring the engagements of civil society organizations in the course of Nigeria’s life and struggles hardly gave space for the involvement of the religious civil society groups working in partnership with the other groups. This is in spite of the giant strides made by many Christian religious organizations especially in the education and health sectors ← 21 | 22 → as well as in the advocacy for human rights issues since independence. Many authors rather concentrated their efforts on exploring the struggles of other civic groups for the return to democratic rule during the military era.7 Others have researched the contributions of civil society in the present democratic dispensation.8 Some authors such as Kukah have given some attention to the role of religion in the society.9 However, the detailed examination of the how and to what extent religion could be involved as part of civil society, and in cooperation with other civic groups, remains to be tackled.

A work of this nature requires systematic and detailed research both in the areas of the social teachings of the Church and of the societal and state issues at stake in the country. This therefore necessitates the application of both interdisciplinary studies as well as other accompanying relevant theoretical dialogue.

To this end, this researcher will study the social encyclicals of the popes in addition to other relevant literature in relation to the social engagements of the Church. He will also research into available literature in the area of civil society particularly in Nigeria and in the African region—and, of course, other relevant materials outside Africa. Other related literature in the area of Nigeria’s political governance will as well be of critical importance. This work is thus mainly a literature-based study. The literature materials are chosen according to their relevance to the theme under examination. The use of various libraries at his disposal are therefore of vital importance.

Regarding the method of choosing literature, most of the works for this study were chosen from the period of the 1990s to date, except the ones dealing with the histories of the civil society of Nigeria and the literature dealing with the Church and its social concerns. The choice to limit the literature to the 1990s is due to the fact that the period between independence and the late 1990s had different sociopolitical situations and as such presented different challenges to the Church and other civil groups. For example, the pre-colonial and colonial eras were occupied with the country’s formation. That period had a robust civil society. Again, the 1970s to the 1980s were faced with military rule and were encountered by an equally vibrant civil society. From the end of the 1990s, Nigeria entered into a ← 22 | 23 → different phase of sociopolitical and economic condition with the return to civil rule. Hence, the main period considered in this study is from the late 1990s onwards.

Furthermore, much church literature concerning the Church itself and other civil society groups—particularly the magisterial teachings on social issues—often span a longer period. For example, Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum was written 1891. Such writings, however, remain critical to the Church’s social relations across the ages. As such, all church documents were considered relevant irrespective of their period of publication.

Some Relevant Literature Examined in this Research

In considering the historical development of western civil society, the works of Ehrenberg10, Jürgen Schmidt11, Alexis De Tocqueville12 and Michael Edwards13 were given priority attention. This is mainly due to their detailed approach and currency of thought regarding the understanding of civil society. Other important researches taken into account include those of Manuel Borruta14, Karl Gabriel15, Baumann16, ← 23 | 24 → Nothelle-Wildfeuer17, and Liedhegener18. On the other hand, the works of John Keane19 and Michael Walzer20 were given limited treatment because they hold strongly that large business entities are included in civil society.21 The latter works could be valuable additions to the debate as to whether large market entities belong to civil society.22 All the aforementioned researches do not, however, ← 24 | 25 → treat the aspect of civil society development as it was or is seen in Africa. That is why the civil society theorists of the African region were given a focused and detailed treatment.

Thus the works of Nelson Kasfir23, Michael Bratton24, Adiele Afigbo25 and Ade Ajayi26 are some of the most important contributions to the knowledge about civil society in Africa and thus considered in this research. There are, however, authors such as Hadenius and Uggla27 who question the existence of civil society in Africa. Basing their arguments on the non-engagement of some of the traditional civil groups with the government, they dismiss them as not qualifying as civil society groups. Their work is not given a detailed treatment because their arguments have been largely overtaken.28

In addition to some of the authors mentioned above, there are works that strongly define the participation of the Church as part of civil society. Of particular ← 25 | 26 → relevance are the two encyclicals of Pope Benedict XVI: Deus Caritas Est29 and Caritas in Veritate30. These are in addition to the Vatican II Council documents Gaudium et Spes31 and the Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity32. Pope John Paul II’s encyclical Centesimus Annus33 is equally important in this respect. It could be said however that Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum34 is a groundbreaking work in the approach to the Church-civil society involvement. There were also other important insights like the statements by the office of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace in the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Catholic Church35 and the German Caritas in the Goals of the German Caritas Association36. The research inputs by Baumann and a team of researchers in the Theological Private University of Linz under the title, Werke der Barmherzigkeit. ← 26 | 27 → Mittel zur Gewissensberuhigung oder Motor zur Strukturveränderung,37 offer some insights into the nature, methods and processes of the caritas engagement of the Church in relation to other civil organizations. There were further noteworthy contributions in the area of the Church’s caritas engagement such as those of Lothar Roos38 and Manderscheid39. On the other hand, other authors like Njoku40 question the authenticity of the caritatve approach of the Church using the social principle of Solidarity41. It gives an important insight in regard to the economic reciprocal dependence among the various peoples of the world. The main direction of his argument, however, betrays a lack of holistic understanding of Solidarity as is understood by the Church. As such his work was given limited attention.42 The above are some of the critical literature examined in this research; they do not exhaust the whole gamut of works explored therein. ← 27 | 28 →

This research is an attempt in the field of practical theology, namely, that of Caritas Science. It is not a work in the field of political science. Furthermore, although references are made to relevant materials that touch on the efforts of church and civil society organizations in Europe in the past, the research does not cover all the works of church and civil society groups in Europe. It should also be noted that the work does not cover the activities of the Church and civil society in the whole of Africa. Although a picture of the African situation is presented, the central focus of the work is Nigeria and how the presence and work of the Church and other civil society groups affect it. At the same time, the aspect of the Church that is mostly examined is the activities of the civil society organizations affiliated with the Catholic Church. References are also made to the contributions of other churches in Africa and in Nigeria in particular.

As a work that has the 21st century in view it ends by suggesting various avenues and measures that can be employed towards making the impact of these relevant organs of the Church and civil society more acceptable to the needs of the time.

1.6. An Overview of Nigeria’s History

1.6.1. Nigeria before Independence

The greater part of pre-independence Nigeria was occupied by multiples of neighboring independent kingdoms that interacted among themselves socioculturally, economically and politically and in many respects. This is not to say that these nations had common cultures or understood themselves as one.43 The emergence of what was to be called Nigeria had its beginning with the coming of the British colonialists that started with their trade explorations in the southern parts of the country, particularly Lagos and the Niger Delta.44

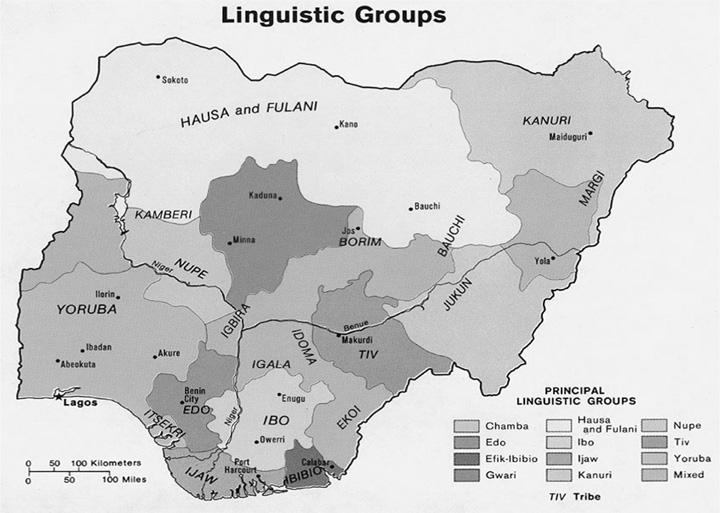

According to Falola and Heaton, pre-independence Nigeria was marked by some major sociocultural, economic and political epochs. In their attempt to present a holistic history of the Nigerian state from the pre-colonial times in ← 28 | 29 → the book A History of Nigeria,45 they tried to trace some of these epochs. In the first chapter, the origins of the different nations that later constituted Nigeria in the Stone, Bronze and Iron Ages (between 9000 BC–1500 BC) were traced.46 The different cultural and political organizations of the various groups of the Hausa states in the northern part of the country as well as the Yoruba and Benin empires in southern Nigeria make it clear that they were independent nations (folks) in those times. What seemed to have led to a closer cooperation between the various nationalities came about during the late 1700 AD and earlier periods of the 1800 AD These were the era of slave trade from Africa to Europe that involved the sale of human labourers from the hinterlands of Benin, Igbo, Yoruba and the northern centres across Africa to Europe. Before then, however, the practice of slave deals among the different nationalities had taken root so that trade routes were well developed between the peoples.47

Furthermore, the missionary activities of various Christian groups that were more firmly established and had presence in both the southern region and the north laid the foundation for the imagination of a united state entity of the African race.48 Ajayi states that it was the Christian missionaries of the early 19th century that impressed upon their African converts the need to unite and form a state that would be comparable to European countries and to the general current international practice.49 Those missionaries included many former slaves of African descent who found their way back to West Africa after regaining their freedom in the early 19th century.50 Ajayi argues that people like Henry Venn—a CMS51 British missionary—was foremost in this dream. It would be interesting to know how widespread this dream was among the missionaries of the different Christian confessions. This is in view of the fact that Venn was a known crusader ← 29 | 30 → for the self-governance of the local churches in his time and yet faced much opposition from his fellow countrymen and clergy.52 There were, however, other historical episodes that prepared the ground for the birth of the Nigerian state particularly in the 19th century.

Other significant events of the 19th century were the political and economic changes due to the Islamic Jihadist invasions into the middle belt region and into the southwestern region of the former Oyo Empire. That invasion of Yorubaland eventually led to the collapse of the Empire.53 The Jihadist crusade of this period resulted in the massive conversion of the Yorubas to Islam as can be seen today in Nigeria’s southwestern states.

Also significant were the incursions of European merchants into new territories surrounding Nigerian nations after their arrival some decades earlier.54 The coming of those merchants led to the massive internationalization of the trade in slaves, resulting in the shipping of millions of people in this lucrative human trafficking business.55 With the abolition of slavery palm oil sales expanded as an international market commodity.56 At this time, British merchants hastened to establish centres of trade in the Delta areas of the Niger River and in Lagos.

The pre-Nigerian epoch concluded with the emergence of British colonialism beginning from the second half of the 19th century. British colonization of Nigeria followed a period of exploration and trade between the locals and Europeans that spanned from the late 15th century to the second half of the 19th century.57 The colonization of the region came in a number of steps. First, the Lagos colony was annexed in 1861 as a protectorate of the British. Then the eastern part of the Niger River was annexed in 1885 and named the Oil Rivers Protectorate58 followed by the Yoruba-speaking western part of the country in 1893. 1900 saw the creation of the protectorate of northern Nigeria but it was only secured with the killing of the Caliph in 1903. Borno, a separate Muslim emirate, was added ← 30 | 31 → in 1904.59 The Lagos colony and protectorate, according to Tamuno60, was joined with the southern protectorate to form the protectorate of Southern Nigeria in 1906. Both the southern and northern protectorates were then joined together in 1914 to form one country—Nigeria. This move was, however, out of purely financial consideration so that the northern protectorate could get monetary support from the southern region to enhance colonial administrative purposes.61 There was no effort to seek the opinion of the people. April 1939 saw the splitting of the southern province into two by the Bourdillon administration, bringing the total number of regions in the country to three. Below is a map of the various nationalities that made up the immediate region of Nigeria before and after colonialism.

Source: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/File:Nigeria_linguistic_1979.jpg

From the late 1920s there began some nationalist movements and agitations against the foreign rule that lasted until the attainment of Nigeria’s independence ← 31 | 32 → in 1960.62 The colonial government did not pay any serious attention to the agitations for self-rule until after the Second World War when in 1948 it declared its intention to incorporate Nigerians into the affairs of governance and took many measures in that regard.63 This development, which Tamuno identifies to be a result of the Second World War, continued until the country finally attained independence in 1960.64

1.6.2. Nigeria since Independence October 1960

At independence Nigeria inherited a three-region subnational government structure from the colonialists. This was mainly a reflection of the various social, cultural and political backgrounds of the three biggest nationalities of the county: Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba.65 These three main ethnic nationalities were only part of over 250 other ethnic nations that had had their own unique organizational structures before colonialism. The result of these large and different sociocultural and political backgrounds was the difficulty in achieving national integration and cohesion.66 Experts observe that the preceding government elites did not make any effort to reshape the structure of the country but continued to maintain the lopsided order as they found it.67 The northern region was much bigger than the eastern and western regions put together. This is despite the fact that the north was not previously culturally homogeneous, which was claimed by the colonialists to be the reason for not splitting it.68 Northern Nigeria thus used its numerical strength to gain greater advantage over the rest of the country in almost all government departments and affairs. The asymmetrical structure of the regional units as well as the political competition among ethnic elites for the ← 32 | 33 → control of the central government, where all the economic wealth was concentrated, led to the failure of the First Republic in 1966.69

The military then came to power with the coup of January 1966, unifying governance to give more powers to the central government.70 General Aguiyi Ironsi was the first military head of state but was later ousted, killed and replaced by Col. Yakubu Gowon after the northern-led counter-coup of July the same year. There followed a serious crisis and a threat of secession by the easterners in 1967 because of the pogroms in the north against the people of their region.71 The threat of secession led the Gowon administration to create twelve states out of the old four regions.72 The country experienced a 30-month-long civil war between 1967 and 1970 because the then eastern region seceded and formed a separate country called Biafra.73

At the end of the civil war in January 1970 the military continued to run the affairs of the country until almost the end of the decade. There followed a short interlude of a four-year return to civil rule which lasted from October 1979 to December 1983.74 The military regime returned and remained in power until the end of the 1990s. During this time, they created more states in the country, leading to the present 36-state structure of Nigeria.75 ← 33 | 34 →

The Administrative Map of Nigeria showing the 36 states and Abuja76 (Source: ILO).

The years of the 1970s to the first part of the 1980s were marked by the oil boom that yielded enormous resources for the government, much of which, however, got wasted in ill-planned projects.77 At the same time, the corruption and dictatorship of the military authorities gave rise to the activities of civil society organizations78 that eventually helped to remove the military rulers from government, making way for the return to civil rule in 1999. The impact of civil society within those years makes it clear how important its contribution could be in bringing about a positive turnaround in some important aspects of national life.79 One of the high points in the activities of civil society was the execution of Ken Saro ← 34 | 35 → Wiwa by the General Sani Abacha government, which sparked worldwide condemnation and strengthened the resolve of civil society to oust military dictatorship from the reins of Nigerian government.80

From the above brief expose, it is clear that the attempt to create a new nation-state out of some hitherto multiple alien nations with different cultures and languages was a herculean task. This is especially so when the protagonist of the action (United Kingdom) did not set out ab initio to achieve this purpose and had neither clear intentions nor the prior consent of the people concerned.81 Moreover, the idea of forming a nation-state outside of one’s own cultural and language group was foreign to the foundation members of Nigeria. This must have led the people to view the formation of the country as a forceful imposition from a foreign political and cultural setting. This may have been one of the main reasons for the short-lived five-year political government after the independence.82 On the other hand, the military takeover and the immediate welcome given to the first coup showed the desire on the part of Nigerians to have an organized, united and developed country. This is in spite of the various failings that have followed the subsequent regimes—military and civilian alike—after the 1966 coup.

It is pertinent to note that the major concern of the majority of the citizens both in the early and current days is not necessarily how to split the country but how to make it work for the good of the present and future generations. Viewed from this perspective, the obvious question arises: what in essence can the stakeholders do to bring about the necessary and possible socioeconomic and political development of the country? Apart from the observed successes and shortcomings both in government and in the economy, in what ways can the citizenry make important contributions to the development of the country? Is there any place for the input of civil society in this regard? In what concrete ways can it contribute to creating the Nigeria of the people’s dream? Does it have the capability for or prior examples from other nation-states for this objective? What are the possible challenges that may hinder the success of its aims and objectives? Does civil society have any prospects in pursuing such a goal? Who are ← 35 | 36 → the possible partners in the efforts towards Nigeria’s socioeconomic and political success? What is the role of the Church and other religious communities, understood as part of civil society? How can they cooperate for the achievement of the desired goal? In these and many other questions lies the subject of this research.

1 See for example the works of the following authors: Uchendu 1965, p. 76ff; van Allen 1972, pp. 165–181; Chuku 2009, pp. 83–87; Forde, Jones 1950, pp. 3–93; Abbott 2006, pp. 61–65.

2 Cf. Ajayi 1961, pp. 197–210; Afigbo 1966, pp. 539–557; Orji 2009, pp. 85–88; Chuku 2009, pp. 87–93.

3 Cf. Kukah 2000, pp. 107ff; The Role of Civil Society in Promoting and Sustaining Democracy in Nigeria, pp. 44ff.; Falola, Heaton 2008, p. 136ff.; Ubaku et al. 2014, pp. 54–67.

4 Cf. Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace 2005, no. 417.

5 In this connection, one must recall the high level of competition and struggle between the various ethnic and regional traditional civil groups; from the north to the south as well as from the east to the west of the country.

6 For a full discussion on this theme see Borutta 2005, p. 1ff. Shobana Shankar also questions the acceptance of religion as part of civil society. See Shankar 2013, pp. 25–41.

7 See for example Kukah 2000; Diamond et al. 1997; Osaghae 1998a; Osaghae 1998b; Falola 1999, pp. 151–221.

8 Cf. Ikelegbe 2005; Osaghae 2006; Ikelegbe 2001; Adebanwi et al. 2013; Obadare.

9 Cf. Kukah 2000, pp. 177–210.

10 Cf. Ehrenberg, John (1999): Civil Society: The Critical History of an Idea. New York, NY: New York Univ. Press.

11 Cf. Schmidt, Jürgen (2007): Zivilgesellschaft. Bürgerschaftliches Engagement von der Antike bis zur Gegenwart: Texte und Kommentare. Reinbek: Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag.

12 Cf. DeTocqueville, Alexis; Boorstin, Daniel J. (1990): Democracy in America, Volume 1. New York NY: Vintage.

13 Cf. Edwards, Michael (2005): Civil Society – Theory and Practice, the Encyclopaedia of Informal Education. Available online at http://www.infed.org/association/civil_society.htm, accessed 10/12/2012; Edwards, Michael (2011): The Oxford Handbook of Civil Society. New York: Oxford University Press.

Details

- Pages

- 447

- Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631730126

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631730133

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631730140

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631730119

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11718

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (October)

- Keywords

- Christianity Caritas Civil Organizations Public Sphere Social Empowerment Social Governance

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2017. 447 pp., 3 b/w ill.