On the Sea Battle Tomorrow That May Not Happen

A Logical and Philosophical Analysis of the Master Argument

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Foreword

- Contents

- Part I Philosophical framework of the topic

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Truth and Sentences

- 2.1 Syntactic approach

- 2.2 Meanings of expressions

- 2.2.1 Propositions as meanings of sentences

- 2.2.2 Pragmatic components of a statement

- 2.2.3 Sentences that are temporarily determined

- 2.2.4 Sentences that are temporarily undetermined

- 2.3 Sentences vs. logical value

- 2.3.1 Requirements for the concept of truth

- 2.3.2 Historical background

- 2.3.3 What owns the truth?

- 2.3.4 What makes sentences true

- 2.3.5 The concept of truth employed in the study, concept of false controversy

- 2.3.6 Presuppositions of sentences

- 2.3.7 Sentences with modalities and other

- 2.3.8 Truth, time vs. epistemic concepts

- 3 Determinism

- 3.1 The extent of determinism

- 3.2 Modal components of determinism

- 3.3 Ontological determinism

- 3.3.1 Physical determinism

- 3.3.2 Metaphysical determinism

- 3.4 The consequences of determinism

- 3.4.1 Logical determinism

- 3.4.2 Epistemological determinism

- 3.4.3 Temporal determinism

- 3.4.4 Anthropological aspects of determinism

- 3.5 Determinism vs. the Reasoning of Diodorus Cronus

- 4 Time

- 4.1 Cultural time

- 4.2 Psychological and phenomenological time

- 4.3 Physical time

- 4.3.1 From psychological time to physical time

- 4.3.2 Time in scientific physics

- 4.3.3 Absolute time

- 4.3.4 Relative time

- 4.3.5 Properties of the physical time

- 4.4 Time measurement, its accuracy and units

- 4.5 Philosophy of time and its problems

- 4.5.1 Substantial time vs. attributive time

- 4.5.2 The direction of an arrow of time

- 4.5.3 McTaggart’s problematique

- 4.6 Formal representation of time

- 4.6.1 Attempts to define moments of time: momentsas points vs. moments without points

- Part II The issues

- 5 The problem

- 5.1 Aristotle and The Sea Battle Tomorrow

- 5.1.1 Primary problems concerning modality

- 5.1.2 Interpretations of De Interpretatione

- 5.1.3 On Interpretation IX vs. The Reasoning of Diodorus Cronus

- 5.2 The reasoning of Diodorus Cronus

- 5.2.1 The definitions of modality vs. Diodorus’ reasoning

- 5.2.2 Diodorus’ conditional sentences

- 5.2.3 Conclusions and indications for a reconstruction

- 5.3 The issue of futura contingentia

- 5.4 Research problem and the method used

- 6 Dates, tenses, sentencesvs.time structures

- 6.1 Dates

- 6.1.1 Dates and the pseudo-dates

- 6.1.2 Denotations of the dates

- 6.2 Grammatical tenses

- 6.3 Logical values of the sentences within the time structures

- 7 Logic

- 7.1 Temporal logics

- 7.1.1 Temporal interpretation of the positional logic

- 7.2 Time for the point moments

- 7.2.1 The similarity of the moments, branches and time

- 7.3 Axioms of the logical structures of time

- 7.4 The outline of logics of time R

- 7.4.1 Grammar

- 7.4.2 Axioms and rules of deduction

- 7.4.3 Semantics

- 7.5 Tense logic

- Part III Solutions

- 8 Reconstructions with operator R

- 8.1 The Reconstruction of F. S. Michael

- 8.1.1 Preliminaries

- 8.1.2 Reasoning

- 8.1.3 Definitions of modality

- 8.1.4 Time structure

- 8.2 Reconstruction of N. Rescher

- 8.2.1 Preliminaries

- 8.2.2 Reasoning

- 8.2.3 Definitions of modality

- 8.2.4 Time structure

- 8.3 Calculation of moments

- 8.3.1 Preliminaries

- 8.3.2 Reasoning

- 8.3.3 Definitions of modality

- 8.3.4 Time structure

- 9 Other reconstructions

- 9.1 Reconstruction of A. N. Prior

- 9.1.1 Preliminaries

- 9.1.2 Reasoning

- 9.1.3 Definitions of modality

- 9.1.4 Time structure

- 9.2 Reconstruction of P. Øhrstrøm

- 9.2.1 Preliminaries

- 9.2.2 Reasoning

- 9.2.3 Definitions of modality

- 9.2.4 Time structure

- Conclusion

- Summary

- Bibliography

- Index

1 Introduction

Imagine the following scene. Here, a man of a reverend appearance, immersed in a philosophical reflection, stands by a picturesque, rocky gulf of ancient Greece. That gulf had already been a theatre of many sea skirmishes in which the Athenians wrestled with their enemies. Its image, therefore, naturally brings up associations with the former battle scenes. This is when Aristotle — who is the reverend man — affected by that scenery and cultivated in contemporary Greece bios theoretikós, asks the famous question: will there be a sea battle tomorrow?

It is quite possible that this scene occurred. What is certain, however — if we resist a philosophical temptation to raise immoderate objections and stick to the common sense plane1 — is that Aristotle actually uttered this famous sentence in such circumstances or he did it elsewhere. All in all, we believe that things of the past belong to a field which may not be affected by anyone or anything. Once shaped, it cannot be altered.

The philosopher’s question did not, however, pertain to the past, but to the future. This question was to illustrate the issue of whether or not the expressions stating something about the future events hold any logical value and thus whether, while making statements about future, we can a priori reasonably believe them being are true or false.

Aristotle was to negatively resolve the problem he faced, opting for the open, underspecified future. He displayed his position in Chapter 9 of On Interpretation, supporting it with the reasoning which then found numerous attempts of interpretation and reconstruction with the use of modern, logical measures. The purpose of this reasoning — as it seems — was to clearly distinguish the field of what used to be from the field of what may or may not happen in the future (further in this book, the argument of On Interpretation shall be often referred to as RA, the abbreviated Reasoning of Aristotle).

Also Diodorus Cronus, a Megarian logician and philosopher, took up this issue in ancient discussions, probably trying to justify a position that the events that are to take place in the future are preordained in a way2. To this ←17 | 18→end, Diodorus made use of a special reasoning (further in the study referred to as RDC, abbreviated Reasoning of Diodorus Cronus)3.

Future4 features — among other things — this difference from the present that, in common experience, it simply does not exist. The more so, there are no events, states of the world, affairs or facts etc.5 that will or may be in the future6. They may indeed — in the best case — only occur.

If however — as Diodorus could have argued — the expressions referring to future events (i.e. events which only will occur!) bear a logical value, the events described by them must be in some way — proportionately to the logical values of the expressions — preordained, even before they occur. Preordained and therefore inevitable and determined.

It would therefore appear that from the objective perspective, the reasoning of Diodorus is in favour of certain concepts of the time and the world that, while ←18 | 19→ensuring a logical value of an expression on the future, lead to a certain version of the fatalism.

Let us briefly look into the issue of expressions. Regardless of whether or not their logical value is preordained before the events described do (or do not) take place, they must contain a time parameter. RDC should therefore take into account both the time of given expression and the section or point in time described thereby. From the linguistic perspective, a reflection on RDC theory must therefore contain certain logic which takes into account the relationship between given language units and the time, more specifically — its appropriate concepts.

On the other hand, in the case of Aristotle’s concept, language and its relationships with the time and the world, expressed in certain explicit and implicit assumptions, are not supposed to determine the logical values of any sentences, but basically leave underspecified at least some of the sentences that describe the future. RA must therefore advocate for a certain asymmetry between the descriptions of the past, present and future world, as they lead to a version of anti-fatalism, hence to a world open to variations of the future events.

In the case of fatalism, the logical values of appropriate language units must of course be based on their relevance against the world described (and in our case, the relevance against the future world). The correctness of expressions gain particular importance as the theory of truth in a classic bivalent approach is also a theory of falsity.

These above preliminary findings show that a study on the concept of Diodorus must give a primary role to the notion of truth and the notion of time.

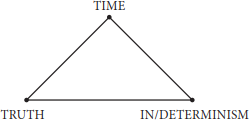

In this case, however, these notions are involved in various relations. Diodorus tried to show that:

- expressions to describe the future are already true or false in the present time, which means that:

- the future is closed in a way, determined.

It seems however that for the expressions about the future to be true:

- the future events must be specified, determined.

The third notion that inevitably appears is therefore the notion of determinism. And a contrario, while advocating for logical indeterminacy of statements describing the future, Aristotle was an advocate of open future and thus of the indeterminism of the future.

These very four notions taken together form the overall conceptual framework within which the philosophical discussion between Aristotle and Diodorus is located.

The above diagram does not give precedence to either of the listed concepts. Only the adoption of the relevant theoretical perspective honours some of them, making them more primary. In view of the chosen perspective, the study gives a particular importance to the concept of time characterised in a specific way, probably familiar to the ancients in a way. However in the case of RDC, it must remain in the defined relationship with the other two concepts. Therefore, the first part of the study shall discuss these three basic components and outline them for two reasons:

- due to the need to situate the ancient discussion in a broader context which will enable explanation of its role and purpose in a rather complete manner, and outlining a number of additional problems that we encounter when describing the philosophical context;

- because of the need to clarify the theoretical assumptions of the study — assumptions without which it would be infeasible to precisely take up the key topic and its further analysis.

When commenting on the individual components, I will try to isolate them as far as possible in order to maintain the general character of the reflection. Of course, this will be neither entirely possible nor desirable. Since the concepts that mark out the framework for the problems of Diodorus reasoning are interconnected, discussing each one separately requires necessarily references to the others. During the analysis and the description of each of them, I will try to determine the expected connection with the subsequent part of the reflection.

1 cf. subsection 1.3.7. Truth and time vs. epistemic concepts.

2 It was argued here that, within his arguments with Aristotle, Diodorus attempted to positively resolve the problem of the sea battle (Prior A. N. [231], s. 138). However, it can be believed that he only meant a temporal characteristics of modal expressions which in ancient times were perceived as leading to a version of determinism. In principle, both subsequent parts of the study are devoted to these problems.

3 The historical, philosophical and logical contexts of this discussion as well as the preserved passages of Aristotle considerations and Diodorus’ reasoning, together with the necessary interpretations shall be exhaustively presented in the next part of the study.

4 When using words: past, present, future, I do not opt for the position of realism in the philosophy of time, corresponding to the so-called A - series ordering according to McTaggart, and thus I decline the position which corresponds to the B -series ordering. I only use these words as natural language constructs by which we globally define what used to be, what is and what will be. The issue of McTaggart’s complex problem and details related to A and B series with reference to the question of Diodorus reasoning shall be further outlined in Chapter 3.

5 For identification of the objective language, I shall use the following expressions: state of affairs event or occurrence (and accordingly, their verb forms: occur and happen). I am going, however, to operate them very neutrally — just like for the words: past, present and future — without opting for any of the ontological schools, but only considering what we are capable of describing using constatives of a natural language. Moreover, I shall discuss this issue in more detail in Chapter 1 where I am going to more evidently advocate for one of the positions.

6 When saying do not exist, I only mean that they do not exist at present. If they did, they would have already taken place by now, and not in the future, should the circumstances allow. This remark is obviously very general and preliminary. Many events — or maybe even all the events, depending on the approach to the structure of the world — are tensely extended. In this very sense, due to the existence in present, they also extend into the future. But before they take place in the future, they may only exist in the present at most, as some stirrings of what is going to occur at a later time.

2 Truth and Sentences

In the present chapter, we shall introduce the issues associated with the language-world reference. Needless to say, the majority of the issues are of a general nature and are the topics of philosophy of language, semiotics and linguistics. However, some appear directly as a result of the considerations relating to the subject of this study, thereby increasing the spectrum of the general concepts. This reason alone is sufficient to justify the fact that many of the concepts will be omitted, some barely mentioned, and certain ones — only indicated. However, the whole chapter constitutes a compact attempt to outline the problematics and the notion of language in terms of the notion of time; it identifies the arising problems, and highlights and presents the assumptions further considered indisputable.

The language we use on a daily basis has many functions. It can be used to express feelings, create new situations, and change others’ attitudes and beliefs. However, carrying out an individual function requires fulfilling a more primary one, commonly referred to as the descriptive–informative function.

Being a part of a human community and benefiting from it requires the participants to be involved in the communication process. This process involves passing information encoded in the language about the broadly defined world. The language is thus a medium enabling communication. Efficient communication depends on various factors. One of them is a matter of understanding a statement or decoding information.

However, communication is not a goal per se. Of particular note is thus — as previously mentioned — the information to be transferred. Statements are particularly valuable when conveying a lot of information on the subject of communication. However, the statements may be carrying little information or even be inconsistent with reality, thus misinforming.

In order to increase the understanding of given statements and to reduce their ambiguity, artificial languages are being created or natural languages clarified. These languages are structured in such a way as to best serve the aim of describing particular objective domain.

Among many classifications dividing statements in particular language, one of the most interesting philosophical (and not just) aspects is the division into true and untrue expressions (false or devoid of logical value).

For the purposes of the study, I would like to determine a few arrangements of the concept of statements, their meanings (content transmitted), logical ←21 | 22→values and finally, I would like to refer these issues to the concept of time. In the subsequent sections of the study, these arrangements shall allow reference to certain issues without their additional clarification.

2.1 Syntactic approach

The deliberations on statement should begin with defining the broad term sometimes used within this chapter. The term in question is declarative statement. By statement, we mean: any graphical sequence of phrases in a particular language, or certain inscription or its phonetic equivalent; compliant with the grammatical structure of given language7.

According to the above definition, the statement does not have to be a sentence in a grammatical sense. However, for quite obvious reasons (that will also be clearly named in this chapter), the statements of interest are either sentences or certain abridgements of sentences, as in some context their utterances fulfil the same informative function as certain sentences. Such statements will be hereafter named declarative statements8. Obviously, by the above definition, statements are related to a particular language used to articulate them, for grammatical and syntactic rules form a language. For example, the following inscriptions:

(1) It is raining.

(2) Haben Sie etwas zu machen?

are statements — respectively — in English and German. As mentioned, sometimes certain phrases not meeting the criteria of syntactic category of a sentence in their informative function are equivalent to other certain statements that belong to the sentence category, namely:

(3) a fifth grade student

Details

- Pages

- 264

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631760796

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631760802

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631760819

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631745892

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14343

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (March)

- Keywords

- Determinism Future contigents Master Argument Sea-Battle Tomorrow Structure of time Temporal logic

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018. 262 pp.