A Grammar of Kusaal

A Mabia (Gur) Language of Northern Ghana

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- 1 Language Profile

- 1.1 Introduction

- 1.2 Geography

- 1.3 Demography

- 1.4 Socio-cultural information

- 1.4.1 Political institutions

- 1.4.2 Religion

- 1.4.3 Family systems

- 1.4.4 Festivals

- 1.4.5 Funerals

- 1.4.6 Marriage

- 1.4.7 Climate and farming practices

- 1.4.8 Linguistic pluralism

- 1.5 Language

- 1.5.1 Language family

- 1.5.2 Dialects

- 1.5.3 Typological sketch

- 1.6 Kusaal research overview

- 1.7 Objectives

- 1.8 Theoretical background

- 1.9 Methodology

- 1.10 Orthography

- 1.10.1 Phonemes

- 1.10.2 Word combinations

- 1.10.3 Pronouns

- 1.10.4 Tone

- 1.11 Organisation of the thesis

- 1.12 Conclusion

- 2 Phonology

- 2.1 Introduction

- 2.2 Phonological inventory

- 2.2.1 Consonants

- 2.2.1.1 Plosives

- 2.2.1.2 Fricatives

- 2.2.1.3 Nasals

- 2.2.1.4 Liquids

- 2.2.2 Some minimal pairs

- 2.2.3 Vowels

- 2.2.3.1 Oral vowels

- 2.2.3.2 Nasal vowels

- 2.2.3.3 Vowel sequencing

- 2.2.3.3.1 Diphthongs

- 2.2.3.3.2 Triphthongs

- 2.2.3.3.3 Epenthetic/intervocalic glottals

- 2.2.4 Vowel harmony

- 2.2.4.1 [ATR] harmony

- 2.2.4.2 Roundness harmony

- 2.3 Tone

- 2.3.1 Morpho-syntactic tone

- 2.3.1.1 The imperfective

- 2.3.1.2 The habitual

- 2.3.1.3 The progressive

- 2.3.1.4 The perfect

- 2.3.1.5 The factative

- 2.3.1.6 Future time marking

- 2.3.1.7 The future interrogative

- 2.3.2 Near-grammatical minimal pairs

- 2.3.2.1 The indicative and interrogative of the perfect

- 2.3.2.2 Negation of the future and the factative

- 2.3.2.3 The imperative

- 2.4 Syllables

- 2.4.1 Peak-only syllables

- 2.4.2 VC syllables

- 2.4.3 The CV syllable

- 2.4.4 The CVC syllable

- 2.5 Word structure

- 2.6 Phonological processes

- 2.6.1 Place of articulation assimilation

- 2.6.1.1 Homorganic nasal assimilation

- 2.6.1.2 Consonant gemination

- 2.6.2 Nasalisation

- 2.6.3 Consonant elision

- 2.6.3.1 Deletion of final –g noun class suffix

- 2.6.3.2 Deletion of coda consonants in compounds

- 2.6.4 Consonant mutation in loanwords

- 2.6.5 Vowel apocopation

- 2.6.6 Vowel coalescence

- 2.6.7 Vowel lengthening

- 2.6.8 Vowel epenthesis

- 2.7 Conclusion

- 3 Nouns, Pronouns and the Noun Class System

- 3.1 Introduction

- 3.2 Structure of the simple noun

- 3.3 Noun types

- 3.3.1 Proper/common nouns

- 3.3.1.1 Personal names

- 3.3.1.2 Place names

- 3.3.1.3 Days of the week

- 3.3.1.4 Cardinal points

- 3.3.1.5 Names of established entities

- 3.3.2 Common nouns

- 3.3.3 Concrete/abstract nouns

- 3.3.4 Countable/uncountable nouns

- 3.4 Derivational processes

- 3.4.1 Derived nominals

- 3.4.2 Associative constructions

- 3.5 Pronouns

- 3.5.1 Personal pronouns

- 3.5.2 Emphatic personal pronouns

- 3.5.3 Possessive pronouns

- 3.5.4 Demonstrative pronouns

- 3.5.5 Reflexive pronouns

- 3.5.6 Reciprocal pronouns

- 3.5.7 Relative pronouns

- 3.5.8 Interrogative pronouns

- 3.6 Inflectional processes and the Kusaal noun class system

- 3.6.1 Class 1/2 (-V, -d/-b)

- 3.6.1.1 Suffix variants (Class 1 & 2)

- 3.6.1.2 Sub-class -Ø/nam

- 3.6.1.3 Derivations

- 3.6.1.4 Compounds with –nid, -daan/dim

- 3.6.2 Class 3/4 (-Vŋ/-Ni)

- 3.6.3 Class 5/6 (-r/-a)

- 3.6.3.1 Suffix variants (Class 5 & 6)

- 3.6.3.2 Derivations

- 3.6.4 Class 12/13 (-g/-s)

- 3.6.4.1 Suffix variants (Class 12 & 13)

- 3.6.4.2 Derivations

- 3.6.5 Class 15/21 (-g/-d)

- 3.6.6 Class 19/4 (–f/-i)

- 3.6.7 Class 20/13 (-bil/-bibis)

- 3.6.8 Single class 14 (–b)

- 3.6.8.1 Derivation

- 3.6.9 Single class 22, 23 (–m)

- 3.6.9.1 Suffix variants (Class 22 & 23)

- 3.6.9.2 Derivation

- 3.6.10 Irregular classes

- 3.7 Conclusion

- 4 Nominal Modifiers and Relator Nouns

- 4.1 Introduction

- 4.2 Nominal Modifiers

- 4.2.1 Adjectives

- 4.2.2 Semantic categorization of adjectives

- 4.2.2.1 Dimension

- 4.2.2.2 Physical property

- 4.2.2.3 Colour

- 4.2.2.4 Value adjectives

- 4.2.2.5 Age

- 4.2.3 Distribution of adjectives in Kusaal

- 4.2.3.1 The bʊn-paradigm

- 4.2.3.2 Adjectives in attributive position

- 4.2.3.3 Predicative adjectives

- 4.2.3.4 Post-copula adjectives

- 4.2.3.5 Pluralisation

- 4.2.4 Numerals

- 4.2.4.1 Cardinals

- 4.2.4.2 Ordinals

- 4.3 Relator nouns

- 4.3.1 Body-part nouns as relator nouns

- 4.3.2 zug ‘on top of’, ‘because of’

- 4.3.3 Other sources of relator nouns

- 4.3.4 Relator nouns and the locative marker

- 4.3.5 The nɛ ‘with’ preposition

- 4.4 Conclusion

- 5 Noun Phrases

- 5.1 Introduction

- 5.2 Distribution of NP elements

- 5.2.1 Possessives

- 5.2.2 Noun/pronoun as head of NP

- 5.2.3 Adjectives

- 5.2.4 Numerals

- 5.2.5 Determiners

- 5.2.6 Demonstrative determiners

- 5.2.7 Quantifiers (adverbial quantifiers)

- 5.3 Conclusion

- 6 Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 6.1 Introduction

- 6.2 Morpho-syntactic features of Kusaal verbs

- 6.2.1 Verb configuration

- 6.2.1.1 Stems of the CV/CVV type

- 6.2.1.2 Stems of the CVC/CVVC type

- 6.2.1.3 Stems of the V/VC/ & VV/VVC type

- 6.2.2 Derivational morphology and verb extensions

- 6.2.2.1 The causative

- 6.2.2.2 The applicative

- 6.2.2.3 The inversive

- 6.2.2.4 The iterative

- 6.2.2.5 The ventive

- 6.2.3 Inflectional morphology

- 6.3 The verb phrase

- 6.3.1 The pre-verbal particles

- 6.3.2 Adverbials

- 6.3.2.1 Place adverbials

- 6.3.2.2 Adverbs of time

- 6.3.2.3 Manner adverbs

- 6.3.2.4 Intensity/degree

- 6.3.2.5 Certainty/probability adverbs

- 6.3.2.6 Frequency adverbs

- 6.4 Conclusion

- 7 Aspect & Modality in Kusaal

- 7.1 Introduction

- 7.2 Aspect

- 7.2.1 The unmarked verb: The factative

- 7.2.1.1 Unmarked action verbs

- 7.2.1.2 Factative 1-verbs and Foc -nɛ

- 7.2.1.3 Unmarked stative verbs

- 7.2.1.4 Factatives and the pre-verbal particles

- 7.2.2 The habitual

- 7.2.3 The progressive

- 7.2.4 Pre-verbals and the IPFV forms

- 7.2.5 The perfect

- 7.3 Modality

- 7.3.1 Future time marking

- 7.3.2 The ingressive clause

- 7.3.3 The conditional clause

- 7.3.4 The imperative

- 7.4 Conclusion

- 8 Clause Structure

- 8.1 Introduction

- 8.2 The role of transitivity

- 8.3 Grammatical relations

- 8.3.1 Subject and direct object/complement

- 8.3.2 Indirect object

- 8.4 Argument structure

- 8.4.1 Single argument clauses

- 8.4.1.1 The existential

- 8.4.1.2 Statives and state-of-affairs verbs

- 8.4.1.3 The perfect

- 8.4.2 Two argument clauses

- 8.4.2.1 Agent and patient

- 8.4.2.2 Experiencer and theme

- 8.4.2.3 Copula clauses/complements

- 8.4.2.4 Locative/motion clauses

- 8.4.3 Three argument clauses

- 8.5 Clause combinations

- 8.5.1 Coordination

- 8.5.1.1 nɛ ‘and/with’

- 8.5.1.2 ka ‘and’

- 8.5.1.3 bɛɛ ‘or’

- 8.5.1.4 amaa ‘but’

- 8.5.2 Subordination

- 8.5.2.1 Complement clauses

- 8.5.2.2 ka ‘that’ as complementiser

- 8.5.2.3 Relative clauses

- 8.6 Conclusion

- 9 Serial verb constructions – A prototypical overview

- 9.1 Introduction

- 9.2 Serialisation

- 9.3 Prototypicality

- 9.4 Some features of SVCs

- 9.4.1 The single event paradigm

- 9.4.2 Same argument sharing

- 9.4.3 The connector constraint

- 9.5 Conclusion

- 10 Pragmatically Marked Structures

- 10.1 Introduction

- 10.2 Focus

- 10.2.1 Broad focus

- 10.2.1.1 nɛ/-nɛ Foc

- 10.2.1.2 n Foc

- 10.2.1.3 -i clitic Foc

- 10.2.2 Narrow focus

- 10.3 Negation

- 10.3.1 Nominal negation

- 10.3.2 Negation of the declarative

- 10.3.3 Future time negation

- 10.3.4 Negation of the imperative

- 10.4 Questions

- 10.4.1 Polar questions

- 10.4.2 Content questions

- 10.5 Context-dependent structures

- 10.6 Conclusion

- References

- Appendices – Kusaal Literary Genres/Texts

- Appendix A – Sɔlim gima ‘Signifying/playing the dozens’

- Appendix B – Kusaal short story

- Appendix C – Kusaal folktale

- Appendix D – Instructional Text

- Appendix E – Kusaal Poems

- Series index

This study describes salient aspects of the grammar of Kusaal, a language spoken in north-eastern Ghana and in the adjoining areas of the Republic of Burkina Faso and Togo. In this introductory chapter, we provide a profile of the language and its speakers as well as the motivation and methods used in the study. While §1.1 introduces the chapter, §1.2, §1.3, and §1.4 talk about the geography, demography and the socio-cultural contexts of the language. In §1.5, we highlight the linguistic situation of the language and provide a review of research around the topic in §1.6. In §1.7 we underscore the objective of the research while the theoretical underpinnings of the research are taken up in §1.8 and §1.9 elaborates on the research methodology employed. In §1.10 we elaborate on the current Kusaal writing system and make a statement of the chapter breakdown of the thesis in §1.11. The chapter is summarised in §1.12.

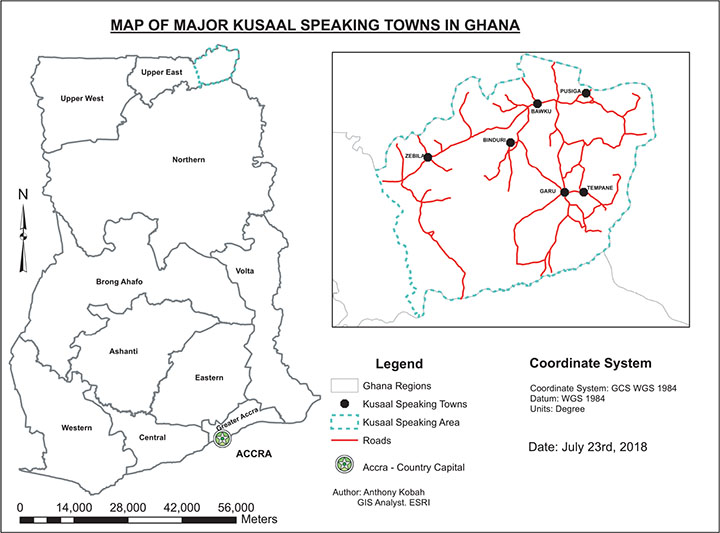

Kusaal is spoken in the north-eastern corner of Ghana and in the adjoining areas of neighbouring Burkina Faso and Togo. The areas within Ghana where the language is spoken are all found in the Upper East Region around latitude 11.050000° N and longitude -0.233333° W. Of the 13 districts in the Region, Kusaal is spoken in 6, namely Bawku Municipal and Zebilla, Garu-, Tempane, Pusiga-Polimakom and Binduri District Assemblies. These are also the most important towns in the Kusaal speaking area including Binaba and Bazua. The location is generally arid, a result of the generally long seasons of dryness followed by intermittent rains over a 4-month period (June to September) each year (see Figure 1.1 below).

Kusaal is one of approximately 50 or so languages spoken in Ghana (Dakubu 1988, Anyidoho and Dakubu 2008). This number includes two non-indigenous languages of wider communication (LWC): English and Hausa; two sign languages (SL): Ghanaian SL and Adamorobe SL, and a simplified LWC, Ghanaian Pidgin English ← 25 | 26 → (GPE), used mostly among young people. Kusaal2 is the formal name of the language while the speakers are called Kusaas (Kusaa for singular). Kusaug is the term used to refer to the contiguous area within which Kusaal is spoken. The speaker population of the language, per estimates from the listings on Ethnologue (Simons and Fennig 2017), number 420,000 people in Ghana alone.3

1.4 Socio-cultural information

The six administrative assemblies of the Kusaal speaking area: Bawku, Binduri, Pusiga-Polimakom, Garu, Tempane and Zebilla correspond to six political constituencies. Representatives of the people are voted based on Universal Adult Suffrage into Parliament, the law-making body of Ghana. These representatives work in close hand with the authorities at the assemblies (local level administrative offices) to improve on the lot of the people. Traditional authority is vested in the Paramount Chief of Kusaug (presently Naba Abugrago Azoka II). He embodies a number of important roles in the traditional affairs of the people including being a ceremonial figurehead and the last resort of traditional adjudication on civil offences in the Bawku Traditional Area. To assist him in his duties are the traditional representatives (divisional and sub-chiefs) in the various small towns and villages across Kusaug. Syme (n.d.) provides an insightful history of the Kusasis with particular regard to the office of chieftaincy with its attendant colonial and ethno-political undertones. (See also Cleveland 1980: 97–113 for an elaborate description of the history of the people and the onset of chieftaincy and its associated issues.)

Majority of the people are adherents of Traditional African Religion followed by Islam. The high presence of Islam is attributed to the conquests of Jihadists and early Muslim activity in the area long before the advent of Christianity. Islamic religious influences are thus found incorporated into some practices of the people including Kusaal naming systems and the Muslim garb. This is equally true of ← 26 | 27 → several parts of northern Ghana where Islam has taken over some of the beliefs and practices of the people such as is found among the Walas of the Upper West region and the Dagbambas of the Northern Region. There is also a significant number of Christians in the general area.

Family systems tend to be extended in nature with traditional Kusaa families comprising parents, grandparents, children, cousins, aunts and uncles, nieces and nephews amongst others. As regards marriage, polygyny is not uncommon with the concomitant large family sizes and plurality of children considered by many as signals of economic and social wellbeing.

The biggest festival of the Kusaas is Samanpiid ‘cleaning of the compound or outside of the house’. This is generally celebrated after the farming season when everyone has harvested their crops and brought them home for threshing. The husks and other unwanted components are then cleaned away in a traditional ceremony to mark the end of the farming season and to thank the gods and ancestors for a bountiful harvest. The festival is often celebrated across the towns, villages and suburbs of the area with a grand event usually held in one of the more important towns. There is also another post-harvest festival, the Yong festival, but this is not as well known or patronised by many.

Ceremonies for dead relatives are often solemn but elaborate affairs. On the death of a person, family members, community members and other well-wishers gather at the house of the individual to mourn with the family. All family members including in-laws and relatives far off are expected to attend and to contribute in making it a successful event. Generally, the official burial ceremony is held not long after the demise of the individual. This is then followed by a final funeral service usually held forty days after the person’s death. ← 27 | 28 →

Figure 1.1: Kusaal language area

In some jurisdictions, however, the forty-day period could be surpassed resulting in the final funeral rites being performed long after the death. At the final funeral rites, the fanfare is greater especially if the dead person lived a long live and died at a ripe old age.

Marriage is an important social achievement among the Kusasis. All people of marrying age are encouraged to marry; girls of 16 years and boys up from 18 can marry. Dowry is paid by the family of the boy to the girl’s family and usually involves some number of livestock. Not until recently, the dowry included four cattle, a goat, a sheep and a number of guinea fowls together with some food and household items. The number of cattle has since been reduced to two for a number of reasons; to enable more young people to go into marriage and to eliminate the risk of men thinking that they have bought off their wives because they paid huge dowries.

1.4.7 Climate and farming practices

We cull the following from Cleveland (1980) to contextualise the state of the climate, farming and agriculture in the Bawku area.

The Kusaal speaking area has savannah type vegetation with grasses predominating. High temperatures and low levels of precipitation in a single rainy season characterise the savannah (p. 70). Like most savannah farmers, the Kusaas depend on rainfall for growing most of their food supply. But while annual distribution of rain is divided into distinct wet and dry seasons, distribution within the wet season is highly variable in time and space. This uncertain rainfall, along with the high rates of evapotranspiration4 produced by high temperatures, make the savannah farmers’ job a difficult one at best. Environmentally, this area is more vulnerable to degradation than the forest area to the south and is also the region where most indigenous forms of intensive agriculture are found. Because of its sparser vegetation and more level surface, it has often been seen as having great potential for supporting large-scale irrigation and/or mechanised agriculture (p. 68).

In addition to the foregoing, he remarks that agriculture is characterised in the northeast as “a custom and not a business, with the result that … the maximum is left to nature” (Lynn 1937: 10 cited in Cleveland 1980: 115). Indigenous ← 29 | 30 → grain and legume crops dominate: millet, sorghum, rice, cowpeas, and bambara groundnuts. The methods by which they are grown, however, vary widely from extensive slash and burn to very intensive fixed cultivation. A large variety of naturally occurring food resources are also known and exploited, although they tend to be used less and less with the development of more intensive agriculture (p. 115). The intensity of traditional agriculture in Kusaug is increasing, in terms of land use, and probably labour input, while culture, economics, and the physical environment limit technical intensification. Traditional agriculture in Kusaug has been adapted to the social and physical environment through constant change, and farmers continue to be willing to change if they see an advantage in it. Under existing environmental conditions and the high and increasing population densities, Kusaa agriculture is unable to check the process of increasing land degradation and loss of productive capacity, which exacerbates the food shortage. While the diet is adequate qualitatively, it suffers from yearly seasonal shortages (p. 155–156).

Language pluralism/multilingualism is one of the major facets of the language landscape in much of Africa and especially so in the Kusaal area. Jungraithmayr et al. (2002: 127) state that apart from the dominance of European languages such as English and French, it is not uncommon for African communities to use not only the language of wider communication in the community (such as Hausa or Twi) but to also use one or more other languages together with the mother tongue. This view resonates Berthelette’s findings in a sociolinguistic study of the Kusaal speaking population (2001). On the whole, Kusaas use Kusaal at home and in the wider community in areas where Kusaal is the dominant language. As a result of mutual intelligibility, the language users also have access to other languages in the wider community such as Mampruli and Moore. Moore has an added advantage in terms of its high speaker population that live just across the border in Burkina Faso and who have a huge presence in the Bawku area as well. While English is used chiefly in official places of work and in the churches in the area, Hausa predominates in the market places and around the mosques and town centres of the more cosmopolitan areas. Heavy code-switching between the local languages and English is also quite wide-spread. Multilingualism is thus accepted as the norm rather than the exception with many Kusaal speakers possessing varying levels of fluency in not only languages like Bissa, Gurenɛ and Bim (Moba), which are spoken in the general area, but also Asante Twi, which is spoken mainly in the southern part of Ghana. ← 30 | 31 →

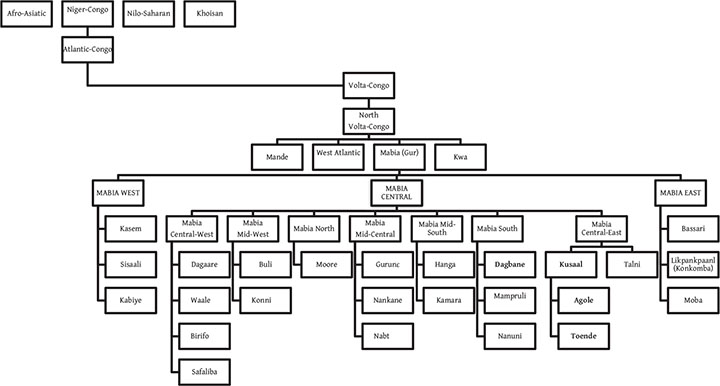

Kusaal is a Niger-Congo language. It belongs in the North Volta-Congo (NVC) grouping of the Atlantic-Congo languages. In the NVC group, Kusaal is clustered traditionally under Gur, which we prefer to call Mabia, and is represented schematically as follows:

(1) Niger-Congo < Atlantic-Congo < Volta-Congo < North Volta-Congo < Mabia (Gur) < Mabia Central < Mabia Central East < Kusaal: Agole, Toende

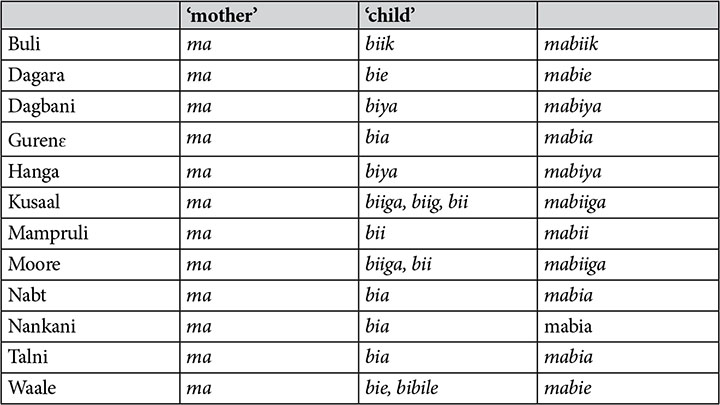

Mabia is used as a replacement term for the group of languages which have hitherto been referred to as Gur. The first usage of the label is traced to Bodomo (1993) inter-alia and is adopted by Musah (2010) among others who consider the label as more encompassing and aptly definitive of the languages in the group. The appropriateness of the Mabia name is attested by the fact that it is a combination of two lexemes, ma ‘mother’ and bia ‘child’ which runs across many of the languages in the enclave. In all these languages too, the meaning of such a concatenation is the same and translates as ‘my mother’s child’ or more precisely ‘my brother/my sister’. To put this into perspective, the examples from the core Mabia cluster below suffice:

Table 1.1: Mabia – ‘My brother/my sister’

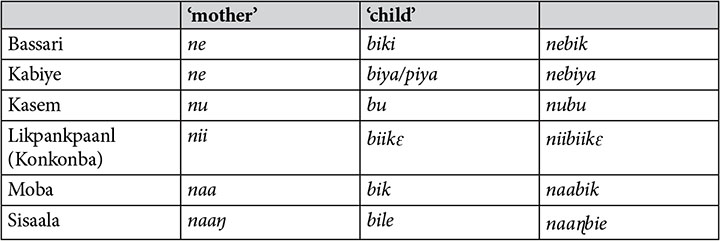

Interestingly, with the exception of Gurenɛ, which actually has gur in its nomenclature and perhaps, following a detailed historical reconstruction, Kusaal, none of the languages in Mabia Central has gur occurring anywhere in their names. Further, though the token items above relate to the central members (see modified family tree in Figure 1.2 below), the six languages in Mabia East and West also highlight an important facet of the new and encompassing name as highlighted in Table 1.2 below. From the token lexemes too (in Table 1.2), one can easily identify the proto-form for ‘child’ in the languages and the similarly consistent proto-form for ‘mother’.

Table 1.2: Extensions of Mabia

As a result of the foregoing, it is therefore not surprising that in the last few years the Mabia label has gained more grounds especially amongst native speaker linguists from the general geographical area who see the name as being “native, more meaningful, neutral, and common in the languages under this subgroup” (Abubakari et al 2017: 3). These languages share not only a similarity in the Mabia name and its apparent (political) correctness but as well several historical antecedents and linguistic features expressed in their tonal patterns, their nominal and pronominal systems, their general word order parameters amongst others (see for instance Bodomo 2017 and Bodomo and Abubakari 2017).

There are two dialects of Kusaal: Agole and Toende spoken in the east and west of the language area respectively, from where they get the labels “Eastern” and “Western” dialects respectively in some of the literature. Each dialect assumes equal status in the language as their respective names suggest: Agole means ‘up’ or ‘high’ while Toende means ‘front’ or ‘ahead’. The Toende dialect is spoken across the border to the north in Burkina Faso while Agole is found to the east ← 32 | 33 → and in Togo. Irrespective of the “superior” names of both dialects, however, Agole has more representation in terms of dialect speakers; some 350,000 as opposed to 87,000 Toende speakers in all the areas where Kusaal is spoken (Simons and Fennig 2017).5 Agole has also received more literary attention and is therefore the written dialect in most of the major books in the language such as the official orthography and translations of the Holy Bible. It is also the medium of instruction in school especially at the University of Education Winneba, where Kusaal has, since August 2014, been studied as a degree subject. ← 33 | 34 →

Figure 1.2: The genetic affiliation of Kusaal

(adapted and modified from Bodomo 1993: 114, 2017: 5) ← 34 | 35 →

Subjects generally precede verbs, which in turn come before objects; complements occur in object position. This ordering is quite strict in Kusaal unlike in a cognate language like Dagbani where the position of the complement is, to some degree, quite flexible. For instance, while the example in (2a) is acceptable, the (2b) is grammatically untenable:

| (2) | Kusaal | ||||

| a. | Adam | ã-nɛ | tampĩir | ||

| Adam | COP-Foc | bastard | |||

| ‘Adam is a bastard.’ | |||||

| b. | *Tampĩir | n | ã | Adam | |

| ‘Adam is a bastard.’ | |||||

However, in the examples for Dagbani below (3), it is possible to topicalise the complement in the canonical clause structure in (3a) by inverting the copula and its complement (Issah 2008: 41) in order to arrive at the sense that is found in (3b) which underlies a focussed construction. This second rendition is however inadmissible in Kusaal even if the clause entails the introduction of a focus paradigm.

| (3) | Dagbani | (Issah 2008: 41–42) | |||

| a. | Ama | nye | la | karimba | |

| Ama | COP | Foc | teacher | ||

| ‘Ama is a teacher.’ | |||||

| b. | Karimba | n | nye | Ama | |

| teacher | Foc | COP | Ama | ||

| ‘Ama is a teacher.’ | |||||

Another intriguing feature of the language is the noun class system, which is one of the most studied topics in the nominal system of many African languages as is, for instance, illustrated in Jungraithmayr et al. (2002), Winkelmann (2001) and Miehe (2012a, b, c) for Niger-Congo languages or in Vossen (1994, 2001, inter-alia) for some Khoesan/Bantu languages. Noun classes denote a tendency for languages to group nominal items together based, for instance, on the alignment of concord markers. More precisely, in the case of Kusaal, these groupings are not motivated by considerations of grammatical gender (i.e., masculine, feminine or neuter) but rather are “nature-based”, i.e., nouns are grouped based on the “human/non-human or living/non-living” dichotomy and on number (Heine et al. 1982: 45). These are exemplified below and discussed in detail in ← 35 | 36 → §3.6. While the first numbers of the classes (1, 3, 5 and 12) refer to the singular class, the second numbers in each class (2, 4, 5 and 13) relate to the plural forms:

Details

- Pages

- 284

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631760833

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631760840

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631760857

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631748688

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14344

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (December)

- Keywords

- language documentation language description under-described languages Bawku, Ghana Mabia (Gur) linguistics

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018. 281 pp., 1 fig. col., 3 fig. b/w, 17 tables