Collective Memory and Oral Text

Summary

The monograph consists of five main parts devoted to the following themes: theoretical considerations, the relation between memory and language, text memory, genre memory, and the relation between memory and the folk artistic style.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface

- About the author

- About the book

- Citability of the eBook

- Table of Contents

- Abbreviations

- Theoretical issues

- I Collective memory: definitions, types, functions

- 1 Memory: collective or social?

- 2 Collective memory: literal or metaphorical?

- 3 Collective memory: a sum total of individual memories, or a supraindividual construct?

- 4 Memory vs. history: relational possibilities

- 4.1 Memory versus history: disintegrating approaches

- 4.2 Memory versus history: integrating approaches

- 5 Collective memory: definitions and attributes

- 6 Collective memory: typological attempts

- 7 Collective memory: functions

- II Cultural heritage – memory – texts of culture

- 1 Memory as a carrier vs. memory carriers: preliminary remarks

- 2 UNESCO’s Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage: definition and scope

- 3 Cultural heritage as a building material of memory

- 4 Memory as a carrier of cultural heritage

- 5 Text of culture as a manifestation of cultural heritage

- 5.1 Text of culture: what is it?

- 5.2 Text of culture: a survey of definitions

- 5.3 Text of culture as a structure

- 5.4 Text of culture as a process

- 5.5 Linguistic (oral) text as a prototypical text of culture15

- 5.5.1 Texts of culture: an analogy to natural language

- 5.5.2 Texts of culture as an amalgam of codes

- 5.5.3 Intersemiotic translation of texts of culture into natural language: selected issues

- 6 Cultural heritage – memory – texts of culture: research and analytical perspectives

- Memory in language – language-embedded

- III Memory depicted in linguistic metaphors

- 1 ‘Metaphor bridges reason and imagination’22

- 2 Memory in linguistic metaphors: a state of research

- 3 Memory as a structure and a process: specific elaborations

- 4 Is memory a language-like entity?

- IV Proper names as carriers of collective memory

- 1 Cooking as language and memory

- 2 Names of dishes as carriers of declarative memory

- 3 Functions of dish names

- Memory and text – text memory

- V Oral text structure as a reflection of memory structure

- 1 Oral text vis-a-vis oral memory

- 2 Text as a memory aid recalling a text from memory

- 3 Text as a memory mirror: textual ways of expressing memory

- 3.1 Text structure based on intertextual memory

- 3.1.1 Intertextual memory: procedural dimension

- 3.1.2 Intertextual memory: the structural dimension

- 3.2 Text structure based on associative memory (keywords)

- 3.3 Text structure based on intertextuality-cum-association memory

- VI Text variation as information about the collective memory functioning of a text

- 1 The double nature of a folklore text as collective memory information

- 2 Folklore text variation: from structure of a text to picture of an object

- 3 Morphological analysis as an examination of an oral text circulation in collective memory

- 4 Text in a social group’s memory: circulation of an oral text

- 5 Folklorism: from cultural to intercultural memory or dialogue with tradition and traditional ways of apprehending folklore

- VII Memory figures versus memory aspects in oral texts

- 1 Memory figures in a research perspective

- 2 Memory in a functional perspective

- 2.1 Time – narration – memory

- 2.1.1 Time vis-a-vis order of discourse

- 2.1.2 Time vis-a-vis order of events

- 2.1.2.1 Creating the world of a narrative

- 2.1.2.2 Time in creating a protagonist

- 2.2 Space – narrative – memory

- 2.2.1 Space vis-à-vis order of discourse

- 2.2.2 Space vis-a-vis order of events

- 3 Reconstructivism as an objective aspect of memory

- 3.1 Mythological reconstructivism

- 3.2 Belief-oriented reconstructivism

- 3.3 Apocryphal reconstructivism

- 3.4 Historical reconstructivism

- 3.5 Family-personal reconstructivism

- 3.6 Ritual reconstructivism

- 4 Subjective aspect of memory: reference to a social group

- 4.1 The addresser of a text

- 4.2 The addressee

- 5 Functions of memory figures

- Memory and text genre – genre memory and genre non-memory

- VIII Memory types versus genre differentiation in folklore texts

- 1 Genres of collective memory and non-memory

- 2 Folklore genre as a factor of collective memory and non-memory

- 3 Memory as a criterion of typologising folklore genres: mnemonic typology of texts of folklore

- 3.1 The criteria of folklore genre differentiation

- 3.2 The memorates-fabulates distinction versus mnemonic typology of folklore genres

- 3.3 Features of memory figures versus genre differentiation of folklore texts

- 3.4 Traditional and modern folklore genres in a memory theory perspective

- 4. Transformations of folklore text genres: from communicative to cultural memories

- Memory and linguistic style – style memory

- IX Memory as a distinguishing value of folk artistic style

- 1 Collective memory style

- 2 Folk artistic style in a folklorist perspective

- 3 Memory as a worldview category

- 3.1 Memory as a source of collectivity

- 3.2 Memory as support of orality

- 4 Formula as a main exponent of memory

- 5 Memory as a treasure of folklore, folklore as a narrative about memory

- Bibliography

- Sources

- List of Diagrams

- List of Tables

Theoretical issues←19 | 20→←20 | 21→

I Collective memory: definitions, types, functions

1 Memory: collective or social?

The terms collective memory (Pol. ‘pamięć zbiorowa’), social memory (‘pamięć społeczna’), group memory (‘pamięć grupowa’), historical memory (‘pamięć historyczna’), or cultural memory (‘pamięć kulturowa’) can all be found in literature on the subject. As noted by Stefan Bednarek (2010: 101), ‘this terminological abundance may well underestimate the issue, but, on the other hand, it allows for a whole array of semantic distinctions. Although all these terms relate to one and the same area, they nevertheless differ in scope’.

The researchers that seem to favour the term collective memory include Maurice Halbwachs (1992), Krzysztof Pomian (2006), Paul Ricoeur (2004), Andrzej Szpociński (2006), Jan Assmann (2008, 2009), Jacek Nowak (2011), and Barbara Szacka (2006, 2012). The term social memory is used by Marian Golka (2009). For some (e.g. Kamilla Biskupska 2011 and Krzysztof Malicki 2012), these two terms happen to be used interchangeably. Yet, some others make deliberate attempts at keeping them apart (for example, the Polish scholars Marian Golka and Barbara Szacka). The divergence that Golka (2009:14) finds between one and the other has to do with the connotations of the corresponding adjectives, social (‘społeczna’) and collective (‘zbiorowa’):

What the adjective social brings to mind is not only collective memory, but also individual memory, which is the one that relates to social issues and is conditioned by social factors. The adjective collective, or group, in turn, may denote a more real [Pol. reistyczny] understanding of memory, as some form of a collective entity.

That Szacka (2012: 16) has opted for the term collective memory comes with advances in social psychology:

Over the last quarter of a century psychology has confirmed Halbwachs’ intuitions about social conditioning of individual memory. (…) It was the recognition of the influence which social factors exert upon individual memory that brought about the concept of ‘social memory’. This is why I assumed that for me, as a sociologist, collective memory is a better general term.

Accordingly, in one of her other works, Szacka (2006: 38) suggests that the term collective memory should be superordinate in relation to social memory, the latter often being considered to be merely informal:←21 | 22→

Two kinds of collective memory can be distinguished within every social group. One used to be called institutional by virtue of its being formally recognised and disseminated by official mass media, while the other one operates outside official circulation and embraces the contents that at times drastically diverge from the contents of the former. Once we distinguish the two, we arrive at various terminological distinctions. (…) As I consider collective memory to be a general term, I tend to call the informal kind social, thus obliterating the alleged synonymy of these two terms.

It is worth looking both of these two adjectives up in dictionaries. Witold Doroszewski’s Słownik języka polskiego identifies społeczny, or ‘social,’ as having the following definitions:

(1) relating to human society; originating, emerging in society; implemented in society; bound with society;

(2) produced, accumulated by society in the production process, brought about by joint efforts, being a public property, belonging to the common good;

(3) obtained, meant to serve the society and their needs; contributing to the common good of society;

(4) implemented, realised by the general public; collective, general;

(5) shared (SJPDor, http://doroszewski.pwn.pl).

Edited by Mirosław Bańko, Inny słownik języka polskiego points to the following four definitions of społeczny:

relating to society, involving its character, ways of organisation, or functions its individual members perform in it;

(1) relating to the attitudes and behaviour of the majority of the members of a society;

(2) produced by society and constituting its common property;

(3) serving to satisfy the needs and improve the living conditions of society (ISJP, II, 654).

The meaning of the adjective społeczny seems to be extended in Praktyczny słownik współczesnej polszczyzny (edited by Halina Zgółkowa):

Bound with society, relating to society, belonging to society, as a product of society as a whole or of its part; collocations: social system, class, social group, social movement, social transformations, great/poor social awareness, reforms, social changes;

(1) meant to satisfy the needs of society as a whole or of its part; also: working towards the good of society, caring for society;

Now, collective ‘zbiorowy’ is given the following definitions: ‘relating to a certain group of people or to a set of things; characteristic of a given set; composed of many units, being a part of a given set; group-like [Pol. gromadny], communal [Pol. kolektywny]’ (SJPDor, http://doroszewski.pwn.pl), ‘relating to a group of people, or (seldom) to sets of things and phenomena’ (ISJP, II, 1305), ‘relating to a group of people or a set of things’ (PSWP, XLIX, 84).

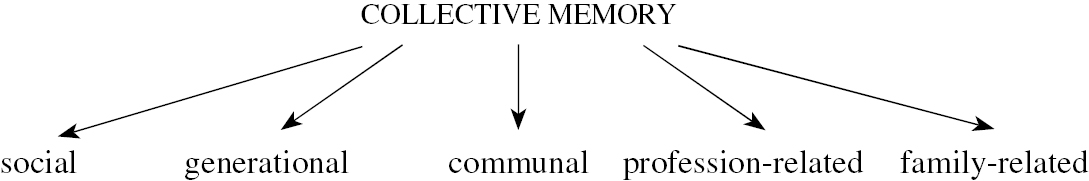

As evidenced in the above definitions, social is related to some general grouping, the whole of society and with social structures. This means that social memory could be understood as a subtype of collective memory, as the latter involves various social groupings, including society as a macrostructure as well as various bigger or smaller microstructures, such as social units of a generational, regional, or subcultural character. I would then opt for collective memory as a superordinate term, whereas social memory would be – next to generational memory, or group memory – one of the subtypes of collective memory. In other words, collective memory embraces various groupings, from society as the biggest to many smaller ones. However incomplete, the following scheme is meant to illustrate some of these distinctions:

2 Collective memory: literal or metaphorical?

There does not seem to be any general consensus as to whether social/collective memory should be taken literally or metaphorically. This echoes the question Paul Ricoeur (2004: 123) asks in relation to what it is that constitutes the actual object of memory processes: who it is that we can ascribe to both pathos (memory reception) and praxis (memory retrieval).

Let us note that even in reference to individual (personal) memory, that is how ‘the inner man [is[remembering himself’ (Ricoeur 2004: 98), Ricoeur uses several metaphorical expressions: ‘spacious palace’ of memory, the storehouse, or the sepulchre ‘where the variety of memories (…) are “stored away”’ (Ricoeur 2004: 98–99). Elżbieta Tarkowska (2012: 29) observes that identifying memory in terms of a store, a supermarket, a reservoir from which relevant themes, subjects ←23 | 24→and objects are derived, is what keeps on recurring in current reflections on memory. According to Astrid Erll, both concepts of, respectively, “cultural” and “collective” memory, have to do with one and the same conceptual metaphor:

The concept of “remembering” (a cognitive process which takes place in individual brains) is metaphorically transferred to the level of culture. In this metaphorical sense, scholars speak of a “nation’s memory”, a “religious community’s memory”, or even of “literature’s memory” (which, according to Renate Lachmann, is its intertextuality). (Erll 2008: 4)

That memory is a metaphor is Marian Golka’s position, too. He describes memory metaphorically as a conversation with the past, and states that in order to survive, every social group must continue this dialogue. In his understanding, memory is “a unique kind of trinity [Pol. trójca], an accumulation of past knowledge, past experiences, and present-day activity” (Golka 2009: 23).

Many memory researchers (e.g., Jan Assmann) follow Halbwachs’ claim that although it can only be an individual that projects memory, a group has also their role to play:

This means that a person who has grown up in complete isolation – though Halbwachs never puts the argument in such a direct way – would have no memory, because memory can only be fashioned during the process of socialisation. Despite the fact that it is always the individual who “has” memory, it is created collectively. This is why the term collective memory should not be read as a metaphor, because while the group itself does not “have” a memory, it determines the memory of its members. Even the most personal recollections only come about through communication and social interaction. We recall not only what we have learned and heard from others but also how others respond to what we consider to be significant. All such experiences depend on intercourse, within the context of an existing social frame of reference and value. There is no memory without perception that is already conditioned by social frames of attention and interpretation. (J. Assmann 2011: 22)

No surprise then, that J. Assmann would strongly emphasise the communicative aspect of memory:

The subject of memory is and always was the individual who nevertheless depends on the “frame” to organise this memory. […] Memory lives and survives through communication, and if this is broken off, or if the referential frames of the communicated reality disappear or change, then the consequence is forgetting. We only remember what we communicate and what we can locate in the frame of the collective memory. (J. Assmann 2011: 22–23)

A similar position is taken by Paul Connerton, who believes that Halbwachs’ concept of collective memory is still plausible providing that we understand that much of what the term embraces is simply interpersonal, rather than collective or social, communication (cf. Connerton 1989: 38).←24 | 25→

3 Collective memory: a sum total of individual memories, or a supraindividual construct?

The question posed in the title of this section involves, in fact, a problem of a relationship between individual (personal) memory and collective memory. Since the publication of M. Halbwachs’ now classic Cadres sociaux de la memoire (Pol. edition: Społeczne ramy pamięci), it has been assumed that individuals’ memories are closely tied in with the social group these individuals belong to. Halbwachs argues that memory depends on its social environment (Halbwachs 1992: 4). It is in a society that an individual acquires memories, learns to identify and recognise them, and where his memories happen to be fostered by what others remember: ‘no one ever remembers alone’ (Ricoeur 2004: 122). A similar position is taken by S. Schmidt, whose argument is that memory and remembering acquire their social dimension not because they are located outside the responsible actors, but because they become dependent on reversible processes of expectation and ascription/attribution. This creates an impression that members of a community tend to think in a given way. In the context of collective memory, then, remembering amounts to a representation which is a derivative of memory understood as either a structure or a competence (cf. Schmidt 2008: 196).

What is, then, collective memory, if it is related to individual memory? Is collective memory merely a background referent for what individuals remember, or is it an independent and autonomous construct?

‘[I]t must first be said that it is on the basis of a subtle analysis of the individual experience of belonging to a group, and through the instruction received from others, that individual memory takes possession of itself’ (Ricoeur 2004: 120). If so, collective and individual memories seem to be closely related, conditioning and supplementing each other, with any attempt at telling them apart being a futile exercise. This is what stems also from Ricoeur’s phenomenological conception of memory: ‘(…) it is this capacity to designate oneself as the possessor of one’s own memories that leads to attributing to others the same mnemonic phenomena as to oneself’ (Ricoeur 2004: 128).

Nevertheless, in Halbwachs’ original insight, collective memory is not meant to be a sum total, or an accumulation, of individual memories, each projected by members of one and the same society. The social framework of memory includes ‘the instruments used by the collective memory to reconstruct an image of the past which is in accord, in each epoch, with the predominant thoughts of the society’ (Halbwachs 1992: 40). An individual remembers assuming the point of view of the group he/she belongs to, but, on the other hand, the memory of the group finds its reflection in what its individual members remember. What ←25 | 26→occurs, then, in-between these two kinds of memories is reciprocal relations, with collective memory being more than a mere sum of individual memories. One notable example of someone who regards collective memory as a sum of individual memories is Jacek Nowak (2011: 9), who states that ‘Collective memory includes in its scope individual memories of the people that constitute societies’. Moreover, he also claims that collective memory is not exclusively a combination of individual memories, or a set of past-representing ideas, but is ‘an act of communication, an activity that results in memory being handed down and recreated in rituals and symbols; the way we remember the past is constantly being adapted to the way we build our identity’ (Nowak 2011: 54).

That collective memory is supraindividual can be found in Manier and Hirst (2008: 254). Though similar to individual memories, collective memories follow their own specific principles: ‘Collective memories are not just gatherings of individual memories, and they cannot be reduced to the principles that relate to individual memories’. In other words, as Manier and Hirst argue, collective memory is not distributed in any simple way in a given society. It must perform a specific function for that society, and this function is mainly identification (Manier and Hirst 2008: 253).

Still, Elżbieta Hałas believes that the analogies and correspondences between collective memory and individual memory are all clear. This becomes particularly evident when one pays attention to the scope of the identification function that both kinds of memory perform:

The conception of collective memory as a property of a social group is built on an analogy to personal memory, which implies that the former is a kind of memory of a collective “person” that – quite like an individual – enjoys its own history that can be told. For a social group, memory – again quite like for an individual – is the basis for preserving identity in time, with looking backwards at one’s own activity becoming a source of social emotions, such as pride or humiliation. (Hałas 2012: 156)

Finally, Krzysztof Pomian takes memory, as much as history, not to be an abstraction, or an idea, but a semiophysical phenomenon, that is a ‘sign system (…) entrenched in material media’. For him, memories are semiophores (Pol. semiofory), or two-sided objects, each being a unity of the semiotic dimension and the material dimension (Pomian 2006: 143).

4 Memory vs. history: relational possibilities

Whenever memory has been approached – in sociology, history, anthropology, or social psychology – some relationship between memory and history has been assumed. These postulated relations appear important in the present book for ←26 | 27→two main reasons. First of all, history is a reference point for memory and, thus provides its definitional basis. The other reason is that the texts we examine here (songs, tales, stories, legends) make references to both local and general history, and are then registers of what and how the country folk as much as the town dwellers remember in relation to history, be it national, communal, or individual. At the same time, memory (what we remember) and remembering (what we recollect) are the gist and parts of the names of some folk genres (e.g. the Polish generic name opowieści wspomnieniowe and its English counterpart recollections are clearly bound with, respectively, wspominać and to recall as two of the terms for ‘to remember’).

How and why memory and history can relate to each other has been a matter of many controversial proposals. These are categorised by Barbara Szacka into two major approaches:

• in traditional approaches, collective memory is denied any unique status of its own and happens to be understood exclusively as a defective (simplified, incomplete) subkind of historical knowledge,

• in postmodernistic approaches, history is denied any unique status of its own and happens to be understood as one of many forms of collective memory (Szacka 2006: 24).

However, yet another distinction seems to be plausible, which is one into:

• disintegrating approaches, where memory and history are considered to be antithetical, unrelated, and mutually independent;

• integrating approaches, where various mutual criss-crossing influences between memory and history are emphasised.

4.1 Memory versus history: disintegrating approaches

That collective memory and history are antithetical to each other goes back to Maurice Halbwachs’ canonical insight that the direction history follows is precisely opposite to the direction that can be found in collective memory (cf. J. Assmann 2011: 28: “it [history] works in a reverse way from collective memory”).

This calls for criteria that may serve the purpose of differentiating between memory and history. One proposal comes from Andrzej Szpociński, who distinguishes three sets of parameters, all complementary in some sense:

• functional criteria, where the focus is on the intent, or the motivation, behind one’s interest in the past;←27 | 28→

• structural criteria, where the focus is on the differences between specific temporal categories;

• cognitive criteria, where the parameter of truth comes to the fore as the most important (Szpociński 2006: 19).

If so, the postulated divergences between history and collective memory1 can be presented in terms of binary oppositions. Nevertheless, it should be stressed that Szpocińki’s parameters are, in fact, idealisations, whereas the divergences between memory and history are a matter of degree and measure. This is why in comparison to a historiographic text, a collective memory driven text will tend to be biased, simplified, temporally cyclic, emotionally-loaded, poetic, equivocal etc.

This binary oppositeness of, or antithetical relationship between, history and memory, should be understood in terms of complementary distribution: if a given feature appears in memory, it does not in history and vice versa. And so, in terms of:

• presence/absence of a social group grounding:

Whereas collective memory looks at the group from inside – and is at pains to present it with an image of its past in which it can recognise itself at every stage and so exclude any major changes – history leaves out any periods without change as empty interludes in the story in order that the only worthwhile historical facts are those that reveal an event or a process resulting in something new. (J. Assmann 2011: 28)

• presence/absence of a cultural text grounding (e.g., place, gesture, picture, object):

In contradistinction to memory,

What history is concerned with is a critical destruction of spontaneous memory. In history’s eyes, the memory of a group appears always suspicious because it aims at the group being disintegrated or persecuted. History may well preserve and appreciate museums, souvenirs, memorabilia, statues, all as useful objects of historical research, but it anyway deprives them of what it is that makes them symbolically significant places of collective memory – lieux de memoire. (Nowak 2011: 35)

Collective memory is evolving, present in the dialectics of remembering and forgeting, assessed in different ways, capable of surviving after having been latent – even if not retrieved for a long time, it may suddenly wake up anew. On the other hand, history is a reconstruction that always appears problematic and incomplete. (Nowak 2011: 35)

Similarly, it is also some other contrasts between memory and history that show binary oppositions:

• continuity versus discontinuity: memory focuses only on resemblance and continuity, whereas history emphasises difference and discontinuity;

• subjectivity versus universality: there are as many memories as there are social groups that preserve and hand down what they remember, but ‘there is only one history, and this shuts out all connections with individual groups, identities, and reference points, reconstructing the past in a tableau without identity’ (J. Assmann 2011: 29);

• partisanship versus impartiality:

History is aware of the complexity of phenomena, stays detached in relation to whatever it speaks about, knows that everything may be approached from different perspectives, comes to terms with the obscurity and multiplicity of motives and behaviours. Collective memory, in turn, is always biased, simplifies problems, and acknowledges only one point of view. Moreover, it does not tolerate any ambiguities as much as it reduces phenomena to the level of mythical archetypes. (Szacka 2012: 15)

• self-interest versus selflessness: History projects extreme selflessness, or an interest in the past for the sake of the past itself:

It is for practical reasons that collective memory addresses the past. This serves the purposes of making certain (cultural, political, social) orders legitimate, and provides the building material for structuring collective identity. (Szpociński 2006: 19)

• simplicity versus complexity;

Details

- Pages

- 374

- Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631819043

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631819050

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631819067

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631808009

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16860

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (March)

- Keywords

- Collective memory Cultural heritage Texts of culture Memory in language Text memory Memory figures Genre memory and Genre non-memory Style memory

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 374 pp., 8 fig. b/w, 12 tables.