"Theories, Techniques, Strategies" For Spatial Planners & Designers

Planning, Design, Applications

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- Developing ‘Adaptive Reuse Strategies’ for Heritage Buildings: A Case Study of Agios Panteleimon Monastery in Cyprus (Kağan GÜNÇE and Damla MISIRLISOY)

- Changes in Open Green Spaces in Post-Pandemic Era (Tuğba DÜZENLİ, Serap YILMAZ and Emine TARAKÇI EREN)

- Designing for/with Syrian Migrants: Sultanbeyli Case (Talia ÖZCAN AKTAN and Özge CORDAN)

- Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Resilience as an Innovative Ecosystem Approach in Sustainable Urbanization (Canan CENGİZ and Aybüke Özge BOZ)

- Drought Tolerant Landscape with Ecological Approach in Sustainable Cities (Elif BAYRAMOĞLU and Seyhan SEYHAN)

- Parametric Design in Architecture Education (Ertan VARLI)

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) and Garden (Elif AKPINAR KULEKCI and Feran ASUR)

- Urban Transplantation: An Analogical Approach on Urban Conservation Interventions (Sanem ÖZEN TURAN)

- Habitat Distribution Shifts of the Oriental Spruce (Picea Orientalis L.) under Climate Change Scenarios (Ömer K. ÖRÜCÜ)

- Landscape Corridors: The Case of Malatya Province (Duygu DOĞAN and Şükran ŞAHİN)

- Urban Development in the Perspective of Ecological Sustainability on a Metropolitan Scale (Duygu Akyol, Doruk Görkem Özkan and Sinem Dedeoğlu Özkan)

- An Implementation with Low Impact Development (LID) Techniques within the Scope of Sustainable Stormwater Management: An Example of Mass Housing Project (Volkan MÜFTÜOĞLU and Halim PERÇİN)

- Urban Agriculture within the Scope of Sustainable and Productive Urban Strategies (Ayşen ÇOBAN)

- A Natural Sustainable Material for Urban Design: Wood (Candan ŞAHİN, Büşra ONAY and Esra MİRZA)

- How to Integrate Green and Grey Infrustructure (Gökçen BAYRAK)

- Human Dimensions of Landscape Planning and Design (M. Bihter BİNGÜL BULUT)

- The Role of Disaster Museums for Disaster Awareness (Gül YÜCEL)

- Spatial Distribution of Human Capital: The Case of Turkey (Seda ÖZLÜ Sinem DEDEOĞLU ÖZKAN and Dilek BEYAZLI)

- Aesthetics in Landscape Design (Serap YILMAZ, Tuğba DÜZENLİ, Elif Merve ALPAK)

- Human Effect on Urban Identity (Selin ARABULAN)

- Planning and Design Approaches for Liveable, Self-Sufficient and Smart Neighbourhoods (H. Selma ÇELİKYAY)

- The Analysis of Urban Health in Bursa Based on Resident Perceptions (Miray GÜR)

- The Examination of the Open and Green Areas of Iskenderun (Hatay) in Terms of Urban Green Infrastructure Planning Principles (Onur GÜNGÖR)

- Rainwater Sensitive Urban Planning – Hydrological Foundations and Planning Principles (Mehmet KARACA, Elif KARACA and Gülseven U. TÖNÜK)

- Evaluation of Renewable Energy Sources in Spatial Decision Process in Urban Planning, Case Study of Balikesir (Serkan SINMAZ)

- Understanding Olivetti Factory as a Sustainable Industrial Heritage (İlke CİRİTCİ)

- Architects’ Opinions on Ecological Building Design and Application Practice (Edirne/Turkey)* (Cenk CİHANGİR and Pınar KISA OVALI)

- Negative Reflections of Political Decisions on Design in Public Spaces (Ezgi ÜLKER BARIŞ)

- Examining the Visual Quality in Environment Choices: The Sample of Coastal Usage in Çanakkale (Between Donanma Tea House and Military Base) (Alper SAĞLIK, Busenur YAMAN, Fatma AKBULUT, Şura YILDIRIM, Tuğçe ÖZDEMİR)

- Vulnerability of Ecosystem Services under the Impacts of Climate Change: A Literature Review (E. Seda ARSLAN)

- The Rise of Nationalist Tendencies in the 1940s; Second National Architectural Movement (Ayşe DURUKAN KOPUZ)

- An Example of Ecology-Based Analysis in Landscape: Landscape Sensitivity Analysis (Aybike Ayfer KARADAĞ)

- A Transdisciplinary Student Design Workshop for an Inclusive In-door Navigation App (Demet A. DİNÇAY, Çağıl Y. TOKER, Elif B. ÖKSÜZ, Sena SEMİZOĞLU, Özge CORDAN)

- Nature-Based Approach in Ensuring Urban Sustainability: Green Infrastructure Strategy (Reva ŞERMET, Nehar BÜYÜKBAYRAKTAR, Fürüzan ASLAN)

- Courtyard Gardens Regulation Principles and Plant Selection in the Historical Process (Feran AŞUR and Elif AKPINAR KULEKÇİ)

- An Evaluation of Contemporary Additions to Refunctioned Architectural Heritage (Banu GÖKMEN ERDOĞAN)

- Instantly Pandemic to Converted Metropolitan City Plan (Gildis TACHIR and Hatice KIRAN ÇAKIR)

- Intra-Forest Recreation Areas as Protected Area Status in the World/Their Legal Status and Current Status (Seyhan SEYHAN and Öner DEMİREL)

- Tourism Corridor Planning Approaches in Urban Areas (Sultan Sevinç KURT KONAKOĞLU)

- Dealing with the Problems of Urban Life in Residential Landscape Design Studio (Sema MUMCU and Duygu AKYOL)

- Forest Bathing as an Eco-Wellness Tourism Activity (Alev P. GÜRBEY and Gülden KARABUDAK)

- Evaluation of the Urban Circulation System in Terms of Pedestrian Use; Kaşüstü/ Trabzon Example (Demet Ülkü GÜLPINAR SEKBAN)

- Agricultural Landscape Planning on the Basis of Conservation and Sustainable Use of Landscapes (A. Esra CENGİZ and Zeynep Burke ÖZDEMİR)

- Participatory Approach in Design (Müberra PULATKAN Dilek BEYAZLI Zeliha AKTÜRK)

- Resistant Cities to Climate Change and Planning Interaction (Demet DEMİROĞLU)

- The Evaluation of the Colors Used in Layouts in Project Competitions: Examples from Turkey (Ahmet BENLİAY and Arzu ALTUNTAŞ)

- The Place of Landscape Design and Applications in Psychological Treatment (Alper SAĞLIK and Çağrı SAVAŞ)

- Universal Design in Playgrounds (Meltem GÜNEŞ TİGEN and Murat ÖZYAVUZ)

- Experiencing the Mixed-Use from Structure to City Scale in the Architectural Design Studio within Architectural Design and Planning (Timur KAPROL)

- The Relationship of Bioclimatic Comfort and Landscape Planning (Oğuz ATEŞ)

- Evaluation of Urban Roundabout Circulation in the Context of Plant Design - Visual Quality - Safety (Mehmet Kıvanç AK and Tahsin YILMAZ)

- How BIM May Change Architectural Education (Mehmet İNCEOĞLU and Bircan İNAN)

- Six Key Issues for Resilient Community Assessment in the Context of Urban Planning Against Disaster Risk (Ayşe ÖZYETGİN ALTUN)

- Semiotic Reading in Landscape Components (Elif SAĞLIK)

- Home Environment Appropriation: Syrian Migrants in Sultanbeyli, Istanbul (Özge CORDAN and Talia ÖZCAN AKTAN)

- Protected Areas (Öner DEMİREL, Seyhan SEYHAN, Atila GÜL)

- Conservation of Historical Urban Landscapes (Beste KARAKAYA AYTİN and Murat ÖZYAVUZ)

- Assessment of Amasra in Terms of Visual Landscape Quality With Its Natural, Historical and Cultural Values (Ömer Lütfü ÇORBACI and Simten SÜTÜNÇ)

- Cultural Heritage in the Urban Planning Studies of Historical Peninsula in Istanbul between 1930 and 1950 (İsmet OSMANOĞLU)

- Assessment of Use in Indoor and Outdoor Subject of Covıd-19 Pandemia Process (Makbulenur ONUR and Selver KOÇ ALTUNTAŞ)

- Ecosystem Services Approach in the Context of Sustainable Environment for Sustainable Development (Rüya YILMAZ and Derya SERBEST ŞİMŞEK)

- Designing Enabling Spaces for Pre-Schoolers: Strategies to Boost Children’s Control Over Spaces (Shirin IZADPANAH and Kağan GÜNÇE)

List of Contributors

Prof. Dr. Kağan GÜNÇE

Faculty of Architecture, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta, Northern Cyprus (via Mersin 10 Turkey)

Assist. Prof. Dr. Damla MISIRLISOY

Faculty of Architecture, European University of Lefke, Lefke, Northern Cyprus (via Mersin 10 Turkey).

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tuğba DÜZENLİ

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Serap YILMAZ

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Emine TARAKÇI EREN

Afyon Kocatepe University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Interior Architecture Environmental Design, Trabzon, Turkey

Talia ÖZCAN AKTAN

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University, Landscape Architecture PhD Programme, Tekirdağ, Turkey.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Özge CORDAN

İstanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department, of Interior Architecture, Istanbul, Turkey.

Assoc.Prof.Dr. Canan CENGİZ

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Department of Landscape Architecture, Bartın, Turkey.

Res.Asst. Aybüke Özge BOZ

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Department of Landscape Architecture, Bartın, Turkey.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elif BAYRAMOĞLU

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Res. Asst. Seyhan SEYHAN

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

←11 | 12→Lect. Dr. Ertan VARLI

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Architecture Department, Edirne, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elif AKPINAR KULEKCI

Ataturk University, Faculty of Architecture-Design Department of Landscape Architecture, Erzurum, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Feran ASUR

Van Yuzuncu Yil University, Faculty of Architecture-Design, Department of Landscape Architecture, Van, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sanem ÖZEN TURAN

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Urban and Regional Planning Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ömer K. ÖRÜCÜ

Suleyman Demirel University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Isparta, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Duygu DOĞAN

Pamukkale University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Department of Landscape Architecture Denizli Turkey

Prof. Dr. Şükran ŞAHİN

Ankara University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Landscape Architecture Ankara, Turkey

Res. Ass. Duygu AKYOL

Karadeniz Technical University, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

Ass. Prof. Dr. Doruk Görken ÖZKAN

Karadeniz Technical University, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey.

Assist. Prof. Dr. Volkan MÜFTÜOĞLU

Bursa Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Bursa, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Halim PERÇİN

Ankara University, Faculty of Agriculture, Landscape Architecture Department, Ankara, Turkey (retired faculty member)

Asssist. Prof. Dr. Ayşen ÇOBAN

Mehmet Akif Ersoy University, Faculty of Engineering Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Burdur, Turkey

←12 | 13→Assoc. Prof. Dr. Candan ŞAHİN

Suleyman Demirel University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Isparta, Turkey

Res. Asst. Büşra ONAY

Suleyman Demirel University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Isparta, Turkey

Esra MİRZA

Suleyman Demirel University, Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture Department, Isparta, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gökçen BAYRAK

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Res. Asst. M. Bihter BİNGÜL BULUT

Kirikkale University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Landscape Architecture, Kirikkale, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gül YÜCEL

Istanbul Gelisim University, Engineering and Architecture Faculty, Department of Architecture, Istanbul, Turkey

Res. Asst. Seda ÖZLÜ

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Urban and Regional Planning Department, Trabzon Turkey

Res. Asst. Sinem DEDEOĞLU ÖZKAN,

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Urban and Regional Planning Department, Trabzon Turkey

Prof. Dr. Dilek BEYAZLI

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Urban and Regional Planning Department, Trabzon Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Serap YILMAZ

Karadeniz Technical University, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, TURKEY

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tuba DÜZENLİ

Karadeniz Technical University, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, TURKEY

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Elif Merve ALPAK

Karadeniz Technical University, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, TURKEY

←13 | 14→Assist. Prof. Dr. Selin ARABULAN

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Prof.Dr. H. Selma ÇELİKYAY

Bartın University, Faculty of Engineering, Architecture and Design, Bartın, Turkey

Assoc.Prof.Dr. Miray GÜR

Bursa Uludag University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Bursa, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Onur GÜNGÖR

Iskenderun Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Iskenderun/Hatay, Turkey

Dr. Mehmet KARACA

Metroplan Consulting and Engineering, Department of Project Management, Ankara, Turkey.

Assist. Prof. Dr. Elif KARACA

Çankırı Karatekin University, Kızılırmak Vocational School, Department of Park and Garden Plants, Çankırı, Turkey.

Prof. Dr. Gülseven U. TÖNÜK

Gazi University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Ankara, Turkey.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Serkan SINMAZ

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Urban and Regional Planning Department, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. İlke CİRİTCİ

Istanbul Gelişim University, Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, Department of Architecture, Istanbul, Turkey.

MSc. Architect, PhD. Candidate Cenk CİHANGİR

Trakya University, Institute of Natural Science, Department of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pınar KISA OVALI

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Edirne, Turkey.

Ezgi ÜLKER BARIŞ

Architect, Guest Lecturer; Tekirdağ Namik Kemal University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture Department of Architecture, Tekirdag, Turkey.

←14 | 15→Assoc. Prof. Dr. Alper SAĞLIK

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, the Landscape Architecture Major of Architecture and Design Faculty, 17020 Çanakkale/Turkey

Busenur YAMAN

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, School of Graduate Studies, Department of Landscape Architecture, 17020 Çanakkale/Turkey

Fatma AKBULUT

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, School of Graduate Studies, Department of Landscape Architecture, 17020 Çanakkale/Turkey

Şura YILDIRIM

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, School of Graduate Studies, Department of Landscape Architecture, 17020 Çanakkale/Turkey

Tuğçe ÖZDEMİR

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, School of Graduate Studies, Department of Landscape Architecture, 17020 Çanakkale/Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. E. Seda ARSLAN

Süleyman Demirel University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Isparta, Turkey.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayşe DURUKAN KOPUZ

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University, Department of Architecture, Tekirdağ, Turkey.

Prof. Dr. Aybike Ayfer KARADAĞ

Düzce University, Faculty of Forest, Landscape Architecture Department, Düzce, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Demet A. DİNÇAY

Istanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Interior Architecture, İstanbul, Turkey

Çağıl Y. TOKER

Istanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Interior Architecture, İstanbul, Turkey

Elif B. ÖKSÜZ

Istanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Interior Architecture, İstanbul, Turkey

Res. Asst. Sena SEMİZOĞLU

Istanbul Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Interior Architecture, İstanbul, Turkey

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tekirdağ, Turkey, PhD. Student

Res. Asst. Nehar BÜYÜKBAYRAKTAR

Kırklareli University Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Fürüzan ASLAN

Kırklareli University Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey

Lect. Banu GÖKMEN ERDOĞAN

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Architecture Department, Edirne, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Gildis TACHIR

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Architecture Department, Edirne, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Hatice KIRAN ÇAKIR

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Architecture Department, Edirne, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Öner DEMİREL

Kırıkkale University, School of Fine Arts, Landscape Architecture Department, Yahşihan, Kırıkkale

Assist. Prof. Dr. Sultan Sevinç KURT KONAKOĞLU

Amasya University, Faculty of Architecture, Urban Design and Landscape Architecture Department, Amasya, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sema MUMCU

Karadeniz Technical University, Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Alev P. GÜRBEY

İstanbul University-Cerrahpaşa, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Planning and Design Department, İstanbul, Turkey

Gülden KARABUDAK

Forest Bathing Guide, Certificated by the Forest Therapy Institute (FTI), İzmir, Turkey

Res. Ass. Demet Ülkü GÜLPINAR SEKBAN

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Landscape Architecture Department, Trabzon, Turkey

←16 | 17→Assoc. Prof. Dr. A. Esra CENGİZ

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Landscape Architecture Department, Çanakkale, Turkey

Zeynep Burke ÖZDEMİR2

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Graduate Education Institute, Landscape Architecture Department, Çanakkale, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Müberra PULATKAN

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Zeliha AKTÜRK

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Trabzon, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Demet DEMİROĞLU

Kilis 7 Aralık University, Vocational School of Technical Sciences, Kilis, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ahmet BENLİAY

Akdeniz University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Antalya, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Arzu ALTUNTAŞ

Siirt University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Siirt, Turkey

Çağrı SAVAŞ

Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, School of Graduate Studies, Çanakkale, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. MEltem GÜNEŞ TİGEN

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architectıre, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Murat ÖZYAVUZ

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architectıre, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Timur KAPROL

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Oğuz ATEŞ

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mehmet Kıvanç AK

Düzce University, Faculty of Forestry, Department of Landscape Architecture, Düzce, Turkey

←17 | 18→Assoc. Prof. Dr. Tahsin YILMAZ

Akdeniz University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Antalya, Turkey

Assoc.Prof. Dr. Mehmet İNCEOĞLU

Eskisehir Technical University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Department of Architecture, Eskisehir, Turkey

Bircan İNAN

PhD Student, Eskisehir Technical University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Department of Architecture, Eskisehir, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Ayşe ÖZYETGİN ALTUN

Kırklareli University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Kırklareli, Turkey

Assist. Prof. Dr. Elif SAĞLIK

Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Faculty of Architecture and Design, Landscape Architecture Department, Çanakkale, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Atilla GÜL

Süleyman Demirel University Faculty of Architecture, Landscape Architecture, Çünür/Isparta

Res. Asst. Beste KARAKAYA AYTİN

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Edirne, Turkey

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ömer Lütfü ÇORNACI

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University, Department of Landscape Architecture, Rize, Turkey.

Assist. Prof. Dr. Simten SÜTÜNÇ

Siirt University, Faculty of Agriculture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Siirt, Turkey.

Assist. Prof. Dr. İsmet OSMANOĞLU

Trakya University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Architecture, Edirne Turkey

Res. Asst. Makbulenur ONUR

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Forest, Department of Landscape Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

Res. Asst. Selver KOÇ ALTUNTAŞ

Karadeniz Technical University, Faculty of Architecture, Department of Interior Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey

←18 | 19→Prof. Dr. Rüya YILMAZ

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Derya SERBEST ŞİŞEK

Tekirdağ Namık Kemal University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Design and Architecture, Department of Landscape Architecture, Tekirdağ, Turkey

Assist. Dr. Shirin IZADPANAH

Antalya Bilim University, Faculty of Fine Art and Architecture, Interior Architecture and Environmental Design Department, Antalya, Turkey

Kağan GÜNÇE and Damla MISIRLISOY

Developing ‘Adaptive Reuse Strategies’ for Heritage Buildings: A Case Study of Agios Panteleimon Monastery in Cyprus

Abstract: Heritage buildings play a significant role in transmitting ones culture to the generations to come. Adaptive reuse strategies can become a practical solution in preserving national heritages once their original roles diminish in time. When applying adaptive reuse strategies, the most crucial stage is to determine an appropriate function.

In order to decide the most appropriate adaptive reuse strategy for the heritage buildings all the factors must be taken into consideration holistically. The aim of the study is to propose a method that can be used in developing adaptive reuse strategies.

As the method, a proposed model, which is developed for adaptive reuse strategies, was investigated. Secondly, The Agios Panteleimon Monastery in Cyprus was observed through site survey as a case study and then, a matrix of various adaptive reuse strategies and alternatives have been formulated and discussed.

The aim of the proposed method is, therefore, of two-folds: to support decision makers in adaptive reuse projects and to inspire architects, designers, engineers, urban planners and restoration experts practicing strategies for adaptive reuse projects. Additionally, the method can be used as a guide for further researches in determining adaptive reuse strategies.

In adaptive reuse decision-making process, it is important to perform a detailed analysis of the heritage building. Incorporated onsite surveys are essential in understanding the behaviour of the heritage building, its background and the needs of the area. In-depth site surveys will ensure a full understanding of the area yielding a better choice of new use for each heritage building if their physical and original values are to be preserved. The continuity of the heritage buildings rely upon the correct choices made. In determining a new function, the factors that impact the adaptive-reuse-strategies need to be evaluated in terms of perspective and adaptability.

Keywords: Heritage buildings, adaptive reuse strategies, decision-making, holistic approach.

1 Introduction

Various internal and external factors induce adaptation of heritage buildings. Buildings become redundant for many reasons like changes in economic and ←21 | 22→industrial practices, demographic shifts or increasing cost of their maintenance. The main reason why they become redundant is because they are no longer suited for the function they were once built for [1]. Once they lost their original function, adaptive reuse is inevitable.

The decision-making process of reuse strategies requires a complex set of thinking over location of heritages, architectural assets and market trends [2]. The participants of the process should have a clear understanding on how to determine the most appropriate future use for buildings [3]. Conflicts often arise between professionals, public, government representatives, architects, architectural historians, developers and owners due to discrepancies in their perspectives [4].

Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings is a challenge for designers [5]. New use proposals should consider if the building is appropriate for this use or preserve the cultural significance of the heritage [1]. Deciding how to use a building is difficult since there are many actors in play. Finding the most appropriate function within a context is crucial in order to preserve and sustain its cultural significance, which would ensure its continuity. During adaptive reuse decision making, finding the most appropriate function for the building and considering the social, economic and physical benefits in different dimensions are important for a successful heritage adaptation.

The tendency is to focus on the technical issues of maintenance and to integrate the preservation activity with the planning of the general land use. However, little attention is paid to the role of management strategies and tactics during their adaptation. The conservation activity should be considered holistically and care should be given to their management for a sustainable heritage adaptation [6]. While assigning new functions, the existing fabric needs to be analyzed in depth. Surveys should be conducted during the decision-making process. The heritage values of the buildings should be considered, the needs of the district should be discovered and possible users of the buildings need to be identified [7].

The main issue in the process is the random decision of the functional changes without methodology, which may result in a short-term use thus ensuring no continuity. In order to find the most appropriate strategy for heritage buildings, the decisions taken for their new use should be based on analytic and scientific methods. Since conservation work is expensive, in the quest for funding economically, socially and physically sustainable buildings, the new uses should be compatible with the heritages. Unfortunately, there is a lack of clear and holistic methodology for an adaptive reuse decision-making of heritage buildings. Although there are some studies for adaptive reuse decision-making, there is a need of a holistic approach in adaptive reuse decision-making. There are existing models that propose methods for adaptive reuse decision-making just for specific functions or for a specific district. On the other hand, Burra Charter [8] suggests steps in planning for and managing the place of cultural significance under three main headings such as understanding significance, developing policies and managing in accordance with policy. However, the model proposes detailed guidance for the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings.←22 | 23→

The study presents a holistic approach in identifying factors affecting the adaptive reuse process and proposes a model that would help decision-makers in developing strategies. The purpose of this research is to question the proposed method when developing adaptive reuse strategies of heritage buildings. In this context, a model proposal has been developed for heritage buildings that are abandoned, inappropriately functioned or disused.

As a method, the model for adaptive reuse strategies of heritage buildings was applied to a case study in Cyprus. New strategies and alternatives were developed for the Agios Panteleimon Monastery in Çamlıbel/Myrtou and a matrix was devised to discuss different proposed strategies. The model has been tested through the application of the case study and a matrix developed in order to propose a quantitative approach. The developed matrix compared three different adaptive reuse strategies. The selected case study was analysed in accordance with the proposed steps and factors. Adaptive reuse strategies were developed and new use alternatives and possibilities were discussed.

2 Literature Review on the Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings

Adaptation of a building is defined as the process of transforming an existing building to accommodate new uses [9]. The term adaptation means the process of adjustment and alteration of a structure or building to fit new conditions. It can be defined as any work to a building to change its capacity, function or performance, which is beyond the maintenance [10]. It may include alterations, extensions, improvements and other works that modifies the building [11].

The Department of Environment and Heritage (2004) defines adaptive re-use as “a process that changes a disused or ineffective item into a new item that can be used for a different purpose” [12]. It is often described as a process by which structurally sound older buildings are developed for economically viable new uses [13]. Adaptive re-use is a process of change that requires creativeness from the architects involved in finding a way to fit a new function for the building and also all those involved in the process [14].

Adaptive reuse is not a recent phenomenon since reuse occurred in the past simply because demolition and the construction of new buildings would simply require more time, energy and money than reuse [14]. It has been started to discuss architecturally during the 1960s and 1970s due to the growing concern for the environment [15]. Much of the original inspiration came from examples of adaptive re-use documented by Sherban Cantacuzino in his two books, New uses for old buildings and Re-architecture: old buildings/new uses [16].

The building reuse and adaptation has become an increasing trend within the last decade [17] and there is a growing perception that it is cheaper to convert old buildings to new uses than demolish and rebuild [18]. Adaptive reuse of buildings is a viable alternative to demolition and replacement since it needs less energy ←23 | 24→and waste. Also it can offer social benefits by revitalizing familiar landmarks and giving them a new life [19]. New life into existing buildings has environmental and social benefits and helps to retain our national heritage; on the other hand, the focus on economic factors alone has contributed to destruction of buildings physical lives [20].

There are various reasons of adapting buildings such as conservation and sustainability. Firstly, reuse of an old building is more ecological than erecting a new building. Redevelopment activities spend more energy and expose more waste than adapting the existing building. Secondly, the historic and architectural significance of existing building can be satisfactory reasons why it should be sustained [11]. The main argument on the reasons of adaptive reuse is a very simple one: it is better to use what is there than making effort to build a new one [21].

At the end of the second millennium, in many European cities there is a clear sign that construction of new buildings is in decline; on the other hand, the reuse of existing buildings is becoming increasingly important. Today, society is more aware of ecological issues and the demolition of old buildings is perceived as an ecological waste and also as the eradication of local identity, of cultural heritage and of socio-economic values [22]. As a strategy to promote sustainability within the built environment, many buildings with cultural and historical values have been adapted and reused instead of demolition [2].

Adaptive reuse can transform heritage buildings into accessible and useable places by providing new places to be lived in a sustainable manner. The most successful adaptive reuse projects respects heritage significance of the building and also add a contemporary layer for its future [12].

3 Research Methodology

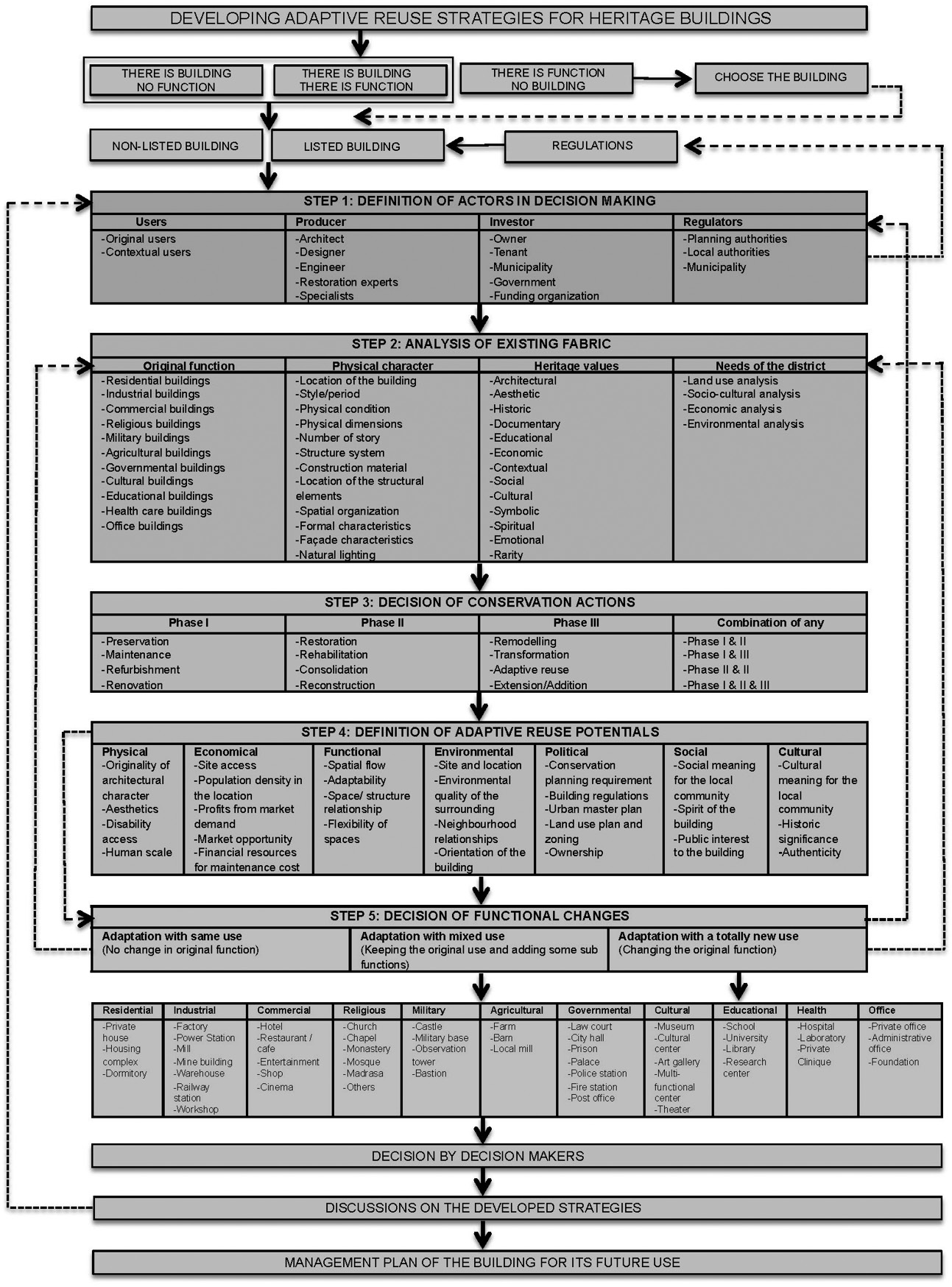

3.1 Model for Developing Strategies for Heritage Buildings

The model proposed steps to be followed in the decision-making process of adaptive reuse. It is applicable to any abandoned, inappropriately functioned or disused heritage building [23]. The adaptive reuse approaches may differ in any other context due to political and planning issues. However, the proposed model can be adapted and used for adaptive reuse strategies of any heritage buildings in any context while considering the policy and planning issues of the locations in concern.

The model can also be used in proposing new strategies for heritage buildings or evaluating the appropriateness of their new functions given that the adaptive reuse project was not successful and further identification of the problems required.

The model proposed a qualitative approach; never the less, the final vote depended on the decision variables of the actors in the adaptive reuse project, context of the heritage building, strategy issues of the related context, and so forth. ←24 | 25→The final decision could only be interpreted and decided after considering pertinent variables.

According to a critical investigation, there are three options of adaptive reuse projects in the decision making process [23, 24]:

i.Possible new uses of abandoned or disused buildings.

ii.Sub-functions to support the existing function.

iii. Researching an appropriate building for the function in hand. For this category, an appropriate building should be chosen before the application of the model. Further research is required regarding the building and its listing by the authorities. For the listed ones, the regulations are the indicators of the decision-making.

Fig. 1.A model for developing adaptive reuse strategies of heritage buildings [23, 24]

3.2 Use of the Model

Deciding on a new use for heritage buildings requires a thorough consideration together with other factors as explained in previous steps. The model represents steps needed in the decision-making. However, the model was not a one-way approach as can be seen by the arrows in Fig. 1. If needed, before moving on it should be re-evaluated before making any decisions.

One of the biggest mistakes in adaptive reuse process of architectural heritages is the application of all conservation actions and finishing interventions then deciding on the new use. This may cause undesirable interventions and inappropriate additions to the heritage buildings by the users in order to adapt the buildings to their new use. User participation in decision-making is crucial. The original and contextual users are the potential users of the buildings but in most of the adaptive reuse projects, they are ignored although users’ contributions, in decision-making, provide healthier decisions.

The objectives of the model were of two-folds: to evaluate the appropriateness of the re-functioned heritage building and to define problems faced in decision-making. The decision was interpreted according to the steps of the model. The second objective was to propose new strategies for the abandoned or disused heritage buildings requiring new lives. The model can be applied to different case studies in order to make appropriate decisions. The new proposals for the future use of the heritage buildings should not only focus on a single category of functions, but be the functional variations of the new proposals.

The decision of the new use alternatives is directly related to the decision-makers. These decision makers are stakeholders of the building. These actors discuss new strategies or as a second option an expert is hired to apply the decided model to buildings in concern and bring the strategy alternatives to the actors. The final decision is taken by the actors in the light of the proposals presented by the decision-making experts.←25 | 26→

←26 | 27→This model is suitable for all locations and listed or non-listed buildings. It can be used by architects, designers, engineers, urban planners and restoration experts in the professional field. Additionally, it can shed light onto future researches.

4 Political and Economic Issues in Conservation of Heritage Buildings in Cyprus

The island is divided into two territories as North and South separated by a UN Buffer Zone since 1974. The buffer zone cuts through the city of Nicosia and divides the whole island from northwest to southeast. A 180 km line of demarcation separates Greek and Turkish Cypriots. The division is the main reason for the island’s on-going problems in terms of restricting development and imposes issues for future planning. In spite of the division, there are efforts on both sides for the conservation and revitalization of architectural heritages. The division limits development and creates diverse problems for planning [25].

Starting from 1986 to the present day, many projects have been conducted funded by The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the European Union through United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) [26]. Since 2001, the European Union funded Partnership for the Future Programme (UNDP-PFF) aims at contributing to the peace and confidence building process in Cyprus through different levels of interventions. UNDP-PFF started working in Cyprus under a bi-communal programme focusing on the rehabilitation of Nicosia; however, in 2004, the programme was extended to other cities namely Famagusta and Kyrenia. In recent years UNDP-PFF’s focus returned to bi-communal projects to support the Technical Committee on Cultural Heritages (TCCH) for the preservation and promotion of the immovable cultural heritages of Cyprus [27]. Generally, TCCH gives more importance to the conservation of abandoned religious heritage buildings in both sectors since it is seen as a threat to the peace and reunion of the island.

Agios Panteleimon, which is selected as the case study of the research is a monastery located in the Northern territory. The different religious beliefs of the two communities living on the island adversely affected conservation of religious heritage buildings. Before the division of the island, Greek Cypriots living in villages were the stakeholders, however, the current stakeholders are Turkish Cypriots. Owing to the current stakeholders of the village and lack of budget to restore heritage buildings, the monasteries and churches are not used today.←27 | 28→

5 Application of the Model on a Case Study

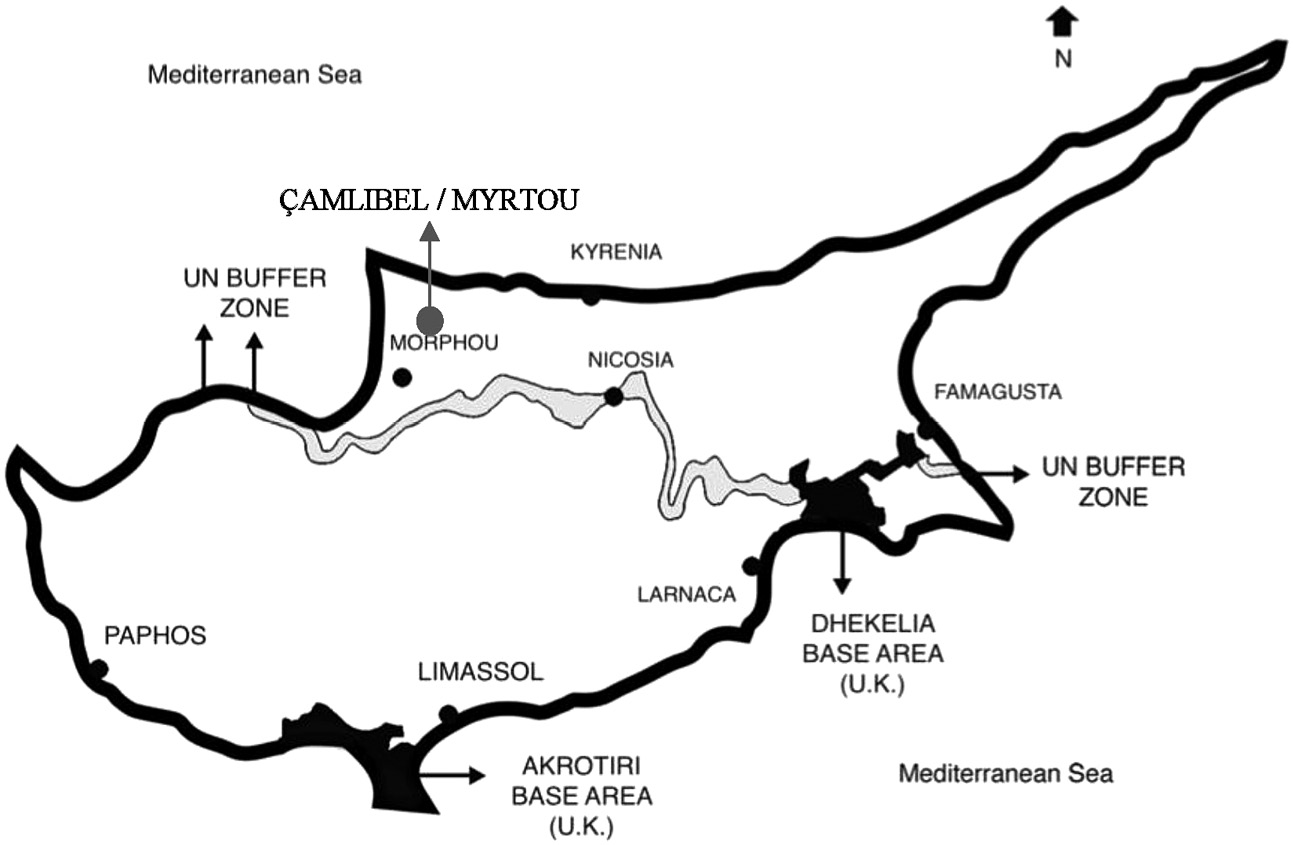

Çamlıbel/Myrtou is an ancient village, on the east outskirts, with the remains of the Byzantine village of Margi. It is located 28 km southeast of Kyrenia city next to Kyrenia – Morphou road (Fig. 2). The village is located on an intersection that connects roads from Nicosia, Kyrenia and Morphou. It has neighbourhood to other villages.

Fig. 2.Location of Çamlıbel/Myrtou on the map

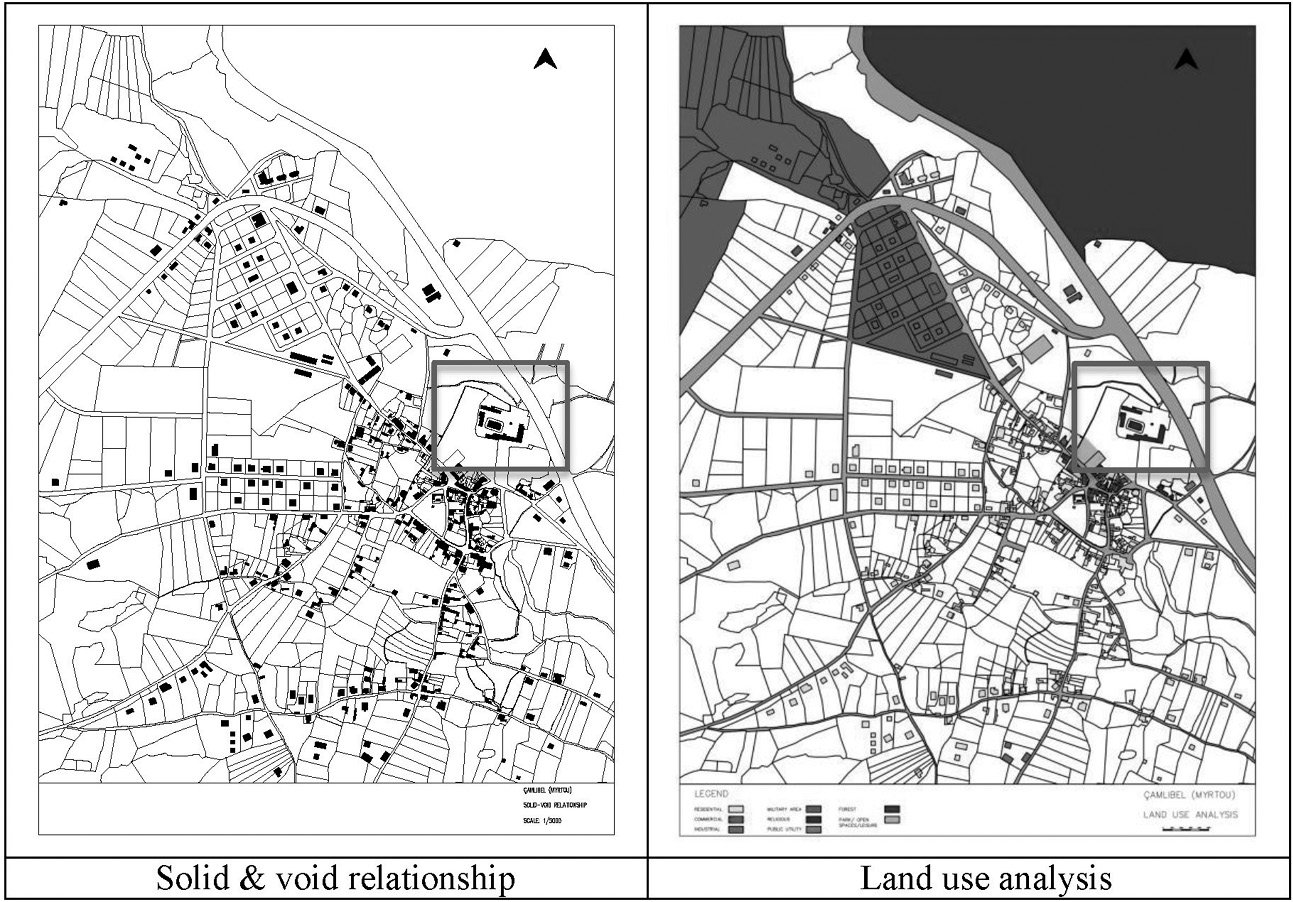

Its principal monument is the Monastery of Agios Panteleimon, which was the residence of the Bishop of Kyrenia from 1571 to 1921 [28]. Agios Panteleimon Monastery in Çamlıbel/Myrtou is a disused and abandoned building (Fig. 3). Adaptive reuse strategies were developed and new use alternatives and possibilities were discussed.

Fig. 3:Solid/void and land use analysis of Çamlıbel village. (Re-drawn and analysis by: Damla Mısırlısoy [29])

The renovation works on the monastery started in October 2015 and completed in 2016. The conservation project was selected by the Technical Committee on Cultural Heritage; (TCCH) United Nations Development Program- Partnership for the Future (UNDP-PFF) supported the project financially [27].

The monastery is a complex consisting of 5 separate blocks of buildings, including a church, dorms, toilets, guest rooms and a fountain. Agios Panteleimon Monastery is unique in terms of its symbolic meaning.←28 | 29→

5.1 Historical Background of the Agios Panteleimon Monastery

Saint Panteleimon Monastery is one of the most famous monasteries in Cyprus. The monastery takes its name from Agios Panteleimon, a saint martyrized at Nicomedia by Maximian, A.D. 303. He was born in 275, and was the son of a rich Pagan father and a Christian mother. The monastery was used by the Bishop of Kyrenia since he had no hegemon of his own [30]. Agios Panteleimon was the patron of saint of doctors. In his pagan youth he studied medicine at Constantinople, and after his conversion to Christianity he cured the deaf, the blind and the lame by prayer alone. Following his martyrdom, his healing powers were said to have transferred into his silver gilt icon at the monastery [31]. The Monastery of St. Panteleimon is the principal monument of the village and its history of the church goes back to the 5th century AD. It is a listed building and its ownership belongs to a foundation (EVKAF) like other churches and monasteries located in the Northern part of Cyprus. Originally, it was a monastery made up of 3 detached buildings and a church in the middle of these three buildings. Block A is the Southern dorms of the monastery, and also the parliament building of the priests. The shorter leg of the L shape was the refectory. Block B in the north was also a dorm and Block C was the common toilets of the monastery. There is a fountain and aqueducts in the courtyard (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4:Visual materials of the Agios Panteleimon Monastery

5.2 Application of the Model on Agios Panteleimon Monastery

The proposed model was applied step by step to the monastery and new strategies were developed for its future use.

Strategy 1 – Adaptation with the same use:

The original users and investors of the heritage strongly believed in preserving the original use of the building. Original users being the Greek Cypriots living on the other side of the island apprehended the building pertinent to their cultural heritages in terms of spiritual and emotional values. The current stakeholders of the village, on the other hand, perceived the building physically as part of a cultural heritage of the district since religiously it has no value to them.

The building was used by the Bishop of Kyrenia from 1571 to 1921 as residence and if returned to this original function, some risks for the future of the heritage building were at stake. First of all, if the building was used as a monastery, lack of use was one of them since the current stakeholders of the village were Muslims. The building then may not be used as effectively and would cause lack of financial sustainability for future maintenance costs. Secondly, using the building as a monastery would engender privacy problems as the locals and tourists might request to visit the building as a preserved monument thus causing further issues for the stakeholders of the monastery. Thirdly, the building had a potential to be used with a function that can create facilities for the current stakeholders especially for the young people and women due to the exiguity of socio-cultural activities in the village. If it is used as a monastery, the building would have no contribution to the socio-cultural development of the area. Therefore, changing the use of the building and selecting the most appropriate new use played an important factor in the economic development of the district thus helping towards new investments.

Strategy 2 – Adaptation with mixed use:

The second strategy for the building was to keep the church with its original function but attribute new uses for the monastic buildings as supporting functions. The church continues to be open for rituals and prayers of the visitors yet its other buildings could accommodate socio-cultural activities of the district.

The monastic buildings could be used as cultural activity centres. Workshops could be organized for children and young people. Art and craft courses for the women living in the village could be administered. Their produce could be exhibited and sold to visitors. Moreover, collaborations could be made with nearby universities as some parts of the building could cater educational activities for their students.

Places like cafés or restaurants should also be provided for the visitors and users of the building. The former refectory of the monastery could be used for this purpose. A block of the monastic buildings could be converted into a boutique hotel and used for accommodation purposes.←31 | 32→

Excavations needed to be done in the archaeological area around the site and the art works found exhibited in the building. Brief historical background information of the monastery should be given to the visitors since the building has distinct narrative. These kinds of activities would promote the economic sustainability of the building for its future maintenance cost. Additionally, they would contribute to the development of the district and its economic growth.

Strategy 3 – Adaptation with a totally new use:

A totally new use could be proposed for the future use of the complex, none the less, according to the factors discussed in the model; this was not a recommended approach in preserving the merit of the heritage building since a totally new use might harm the originality of the building. The physical conservation of the heritage building was not enough, the character and spirit of the building should also be preserved. Throughout the globe, there are many examples of the adaptive reuse of ecclesiastic buildings with obsolete new uses. The local authorities face problems regarding the conservation and rehabilitation of these religious buildings; as a result, they rent or sell them to private users on the basis that they stay the true controlling authority of their future uses. This of course is decided after analysing their heritage values. Every religious building cannot be attributed with a new use. However, if a building is disused, in order to sustain it, a new function is inevitable.

5.3 Findings of the Application of the Case Study

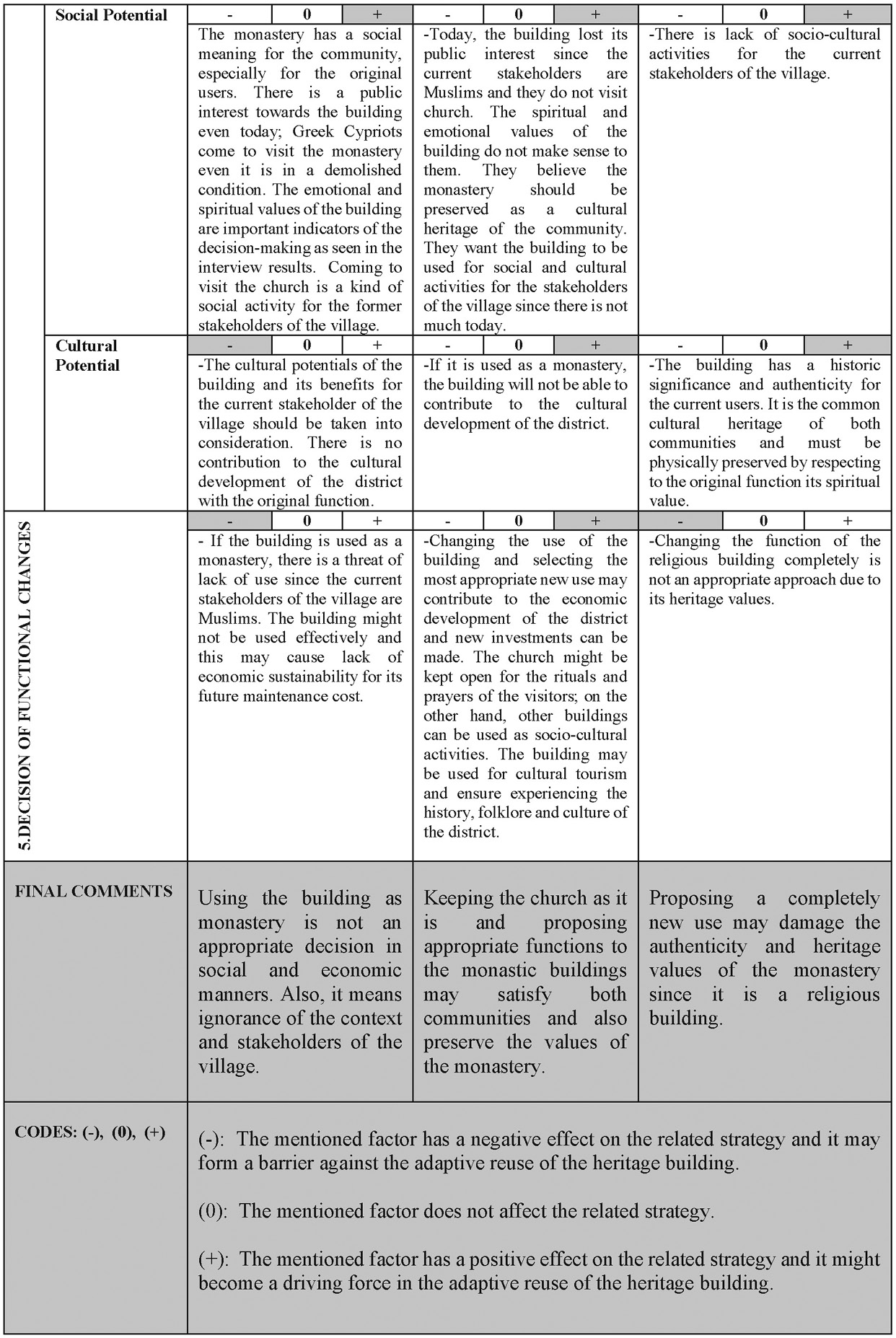

After a thorough discussion of the strategies, in order to attain a quantitative approach, a table which helped comparing the three proposed strategies and select the most appropriate one for Agios Panteleimon Monastery was made. All factors in adaptive reuse decision – making are listed and their effects on the above-mentioned strategies are discussed. These effects are classified in three categories: negative, positive and neutral.

A factor may have a negative effect on the proposal of the new use alternatives in decision-making process thus forming a barrier in the adaptation process. On the other hand, a factor may have a positive effect on the relevant strategy and become the driving force in the adaptive reuse of the heritage building. What is more, a factor may not affect any related strategy. These three effects of the factors and their relationships between the developed strategies are represented in Tab. 1. ←32 | 33→The table helps to evaluate the three proposed strategies in a quantitative and rational approach. Negative and positive effects of the factors should be taken into consideration and proposals should be re-interpreted holistically.

When all factors are evaluated holistically, it is evident that the building if used with the original use, is going to be under a financial threat in future. On the other hand, keeping the church’s original function and proposing other appropriate functions for the monastic buildings may bring satisfaction to both communities while preserving the values of the monastery. Lastly, proposing a completely new use may damage the authenticity and heritage values of the monastery since it is an important religious building and demand in worshipping here remains.

As seen in the analysis, when the negative and positive effects of the proposed strategies are taken into consideration, the most appropriate function for the building is its multi- functional adaptation in compliance with cultural and educational uses for a sustainable heritage adaptation. However, in order to make a final decision, the contributions of all stakeholders and decision makers are essential.

Before the final decision, all actors should come together, discuss relevant issues and reach to a common decision as to which appropriate strategy for the future of the heritage building should be chosen. Community participation and stakeholders’ collaboration is required in developing better adaptive reuse strategies for a sustainable heritage adaptation.

It is of great important to have an in-depth analysis on the needs of the district if an appropriate function is to be assigned for the heritage building. Probing heritage buildings independently of their setting is wrong. The conservation and promotion of the cultural significance of the region should also be taken into consideration. The successful adaptive reuse project of the monastery can act as a catalyst in the district and precipitate other conservation activities in the region. The final decision on the new use of the heritage buildings should be given prior to any interventions; the decision on the conservation actions is the last step in the model. Initially, the new use should be decided and then the building should be designed according to the space requirements of this new use. However, for the monastery, the conservation works started before determining any future use for the building, which might result in undesirable interventions by the users in the future (Tab. 1).←33 | 34→

Tab. 1.Defining the factors as barriers or drivers for Agios Panteleimon Monastery

←36 | 37→It is important to appraise the potentials of the heritage buildings; especially the economic and social potentials should not be ignored for their sustainability. Management and sustainable renovation of heritage buildings, in northern part of the island, incorporate problems. For instance, buildings are physically preserved yet lack living functions due to political issues affecting final decisions. For the continuity of the buildings, international principles are applicable in the adaptive reuse of architectural heritages and the decisions should not be based solely on political matters.

Predominantly, the Department of Antiques and Museums or EVKAF is the property owner of heritage buildings in northern part of the island and all interventions regarding heritage buildings are under their supervision. There are guidelines and regulations in conservation strategies of heritage buildings, however, there are no policies proposing their adaptive reuse strategies. Therefore, new policies should be elaborated in order to develop adaptive reuse strategies while decision makers and community are educated on these matters.

It is important to fully comprehend the significance of the built heritages as living assets rather than just physical assets and preserve them accordingly. It is not possible to convert all heritage buildings into museums, art galleries, and cultural centres. None the less, successful adaptive reuse projects should also be economically sustainable. If there is no threat against their significance, functions like shops, department stores, boutique hotels, cafes or restaurants could be attributed to heritage buildings.

6 Conclusion

Heritage buildings are our identity as they transfer knowledge to new generations regarding lifestyles and cultures of people pertinent to that era. They are the reflections of their time and safeguard the history of communities. A comprehensive conservation and preservation of architectural heritages and giving them new functions according to their location, size, and potential can make heritage buildings sustainable. By the adaptive reuse of cultural heritages, a framework of cultural significance is created.

The life span of a physical structure is longer than its function; therefore, it is necessary to assign a new use for the building once its original function demeans in time. Desolation of heritages causes irrevocable havoc to structures. Nevertheless, any given new function must be appropriate in terms of preserving the cultural significance of their historic fabric. When buildings are reassigned disparate functions, the new use and the interventions should preserve the originality and architectural character of the buildings in order not to give wrong or missing information to future generations.

Before deciding on how to use an abandoned or disused heritage building, a clear definition of all factors affecting adaptive reuse decision-making is of essence. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings is a challenging process since there are many factors involved in an integrated approach, for example, original function, ←37 | 38→physical characteristics, heritage values, needs of the district and potentials of the building should all be holistically contemplated on. In order to question the success of an adaptive reuse project, it is far from being enough to evaluate the project in terms of conservation principles only. An in-depth analysis of existing heritage buildings is fundamental prior to giving them new functions. In a decision-making process, a comprehensive understanding of the district and its context is important and should be secured by surveys conducted on site. It is not enough only to retain the building physically, but the originality of the building must also be preserved by giving an appropriate function and passing it on to appropriate users.

The research proposed a comprehensive methodology for the development of adaptive reuse strategies of heritage buildings and further provided a complete review on the factors affecting decision-making. A model for developing strategies for heritage buildings including industrial heritage buildings or buildings of the Modernism period was proposed all of which were abandoned, inappropriately functioned or disused.

In determining the most appropriate strategy of a heritage building, the adaptive reuse decision-making process should be placed under detailed scrutiny. All the factors of adaptive reuse should be considered from different perspectives. The significance of the heritage, its meaning to the local community and other physical aspects combined should all be taken into consideration. The success of an adaptive reuse project depends on details. It cannot be evaluated in terms of preservation since a successful adaptive reuse project should also be economically sustainable; thereof, bringing in the importance of a solid management plan.

The international principles of conservation of heritages should be harmonized with local needs, beliefs, practices and traditions. No heritage exists without communities as communities create heritages. Loss of unison between communities and their cultural heritages result in loosing identity and bond to locale. For the continuity of heritage buildings, the spirit of the place and local culture should be preserved as well as the physical characteristics of buildings.

The focal point of conservation is to sustain tangible and intangible values of the place. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings can act as a catalyst and onset other projects in the proximity. As mentioned, the contributions of reuse to environment and community are important and cannot be overlooked since there is always an interaction between conversion projects and environment. In order to achieve a successful conversion, the history of heritages should be assessed before entitling appropriate functions.

The model proposed a qualitative approach; the final decision depended on such variables as decision makers, actors in the adaptive reuse project, context of the heritage buildings, policy issues of the related context, etc. The final decision could be interpreted and then decided considering all these variables. The final model can also be applied to several case studies in order to make comparisons and generate discussions as a testing method. In the research, the term ‘sustainability’ is discussed in combination with the term ‘continuity of the cultural heritage’. The ←38 | 39→proposed model can also be adapted and reinterpreted by discussions on social, economic and environmental levels of sustainability.

References

- 1.Orbaşlı, A., Architectural Conservation. 2008, London, Blackwell Publishing.

- 2.Bullen, P.A. and Love, P.E.D., Adaptive Reuse of Heritage Buildings. Structural Survey, 2011-a, 29(5), 411–421.

- 3.Kincaid, D., Adapting Buildings for Changing Uses: Guidelines for change of use refurbishment. 2002, London, Taylor and Francis.

- 4.Yıldırım, M., Assessment of the decision-making process for re-use of a historical asset: The example of Diyarbakir Hasan Pasha Khan, Turkey. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 2012, 13(4), 379–388.

- 5.Langston, C. & Shen, L.Y., Application of the Adaptive reuse application model in Hong Kong: A case study of Lui Seng Chun. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 2007, 11, 193–207.

- 6.Worthing, D and Bond, S., Managing Built Heritage The Role of Cultural Significance. 2008, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing.

- 7.Mısırlısoy, D. and Günçe, K., A critical look to the adaptive reuse of traditional urban houses in the Walled City of Nicosia. Journal of Architectural Conservation, 2016-a, 22 (2), pp. 149–166.

- 8.ICOMOS, Burra Charter, The Charter for Places of Cultural Significance, Online available from: http://australia.icomos.org, 1999.

- 9.Brooker, G. & Stone S., Context and Environment. 2008, Switzerland, Ava Publishing.

- 10.Chudley, R., Maintenance and Adaptation of Buildings. 1983, London, Longman.

- 11.Douglas, J., Building Adaptation. 2002, London, Butterworth-Heinemann Publishing.

- 12.DEH - Department of Environment and Heritage, Adaptive reuse: Preserving our past, building our future. ACT:, 2004, Commonwealth of Australia.

- 13.Austin, R. L., Adaptive Reuse: Issues and Case Studies in Building Preservation. David G. Woodcock, W. Cecil Steward, and R. Alan Forrester, editors. 1988, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

- 14.Velthuis, K. and Spennemann, D.H.R., The future of defunct religious buildings: Dutch approaches to their adaptive re-use. 2007, Cultural Trends, 16 (1), 43–66.

- 15.Cantell, S. F., The Adaptive Reuse of Historic Industrial Buildings: Regulation Barriers, Best Practices and Case Studies. Unpublished Master Thesis, 2005, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.←39 | 40→

- 16.Falk, N., New uses for old industrial buildings in Industrial Buildings: Conservation and Regeneration. 2000, London, Taylor and Francis.

- 17.Bullen, P.A. and Love, P.E.D., A new model for the past: a model for adaptive reuse decision-making. Built Environment Project and Asset Management, 2011-b, 1(1), 32–44.

- 18.Ball, R., Re-use potential and vacant industrial premises: revisiting the regeneration issue in stoke-on-trent. Journal of Property Research, 2002, 19(2), 93–110.

- 19.Conejos, C., Langston, C., & Smith, J., Improving the implementation of adaptive reuse strategies for historic buildings, Aversa and Capri, Naples, 2011, Italy: La scuola di Pitagora s.r.l.

- 20.Shen, L.-Y. & Langston, C., Adaptive reuse potential: An examination of differences between urban and non-urban projects. Facilities, 2010, 28(1), 6 -16.

- 21.McCallum, D., Regeneration and the historic environment in Understanding historic building conservation. Edited by Forsyth, M., 2007, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing.

- 22.Cramer, J., and Breitling S. Architecture in Existing Fabric. 2007, London, Birkhauser.

- 23.Mısırlısoy, D., A holistic model for adaptive reuse strategies of heritage buildings. Unpublished PhD thesis, 2016, Eastern Mediterranean University, Famagusta

- 24.Mısırlısoy, D. and Günçe, K., Adaptive reuse strategies for heritage buildings: A holistic approach, Sustainable Cities and Society, 2016-b, 26, pp. 91–98.

- 25.Oktay, D. An analysis and review of the Divided City of Nicosia, Cyprus and new perspectives. Geography, 2007, 92, No. 3, pp. 231–247.

- 26.Vehbi, B. O. and Günçe, K., Revitalization Studies for the Divided Historic Center: Walled City of Nicosia, Cyprus. XXVI. International Building and Life Congress – Re-invention of City Center, Bursa, April 2014, pp. 313–323.

- 27.UNDP in Cyprus (2016) URL 1: https://www.cy.undp.org/

- 28.Robertson, I., Blue Guide: Cyprus. 1990, London, A&C Black.

- 29.Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus - Land Registry and Cadastre Office/Archive 2017.

- 30.Hackett, J., A History of the Orthodox Church of Cyprus. 1901, London, Methuen & Co.

- 31.Darke, D., Guide to North Cyprus, 1993, England: Bradt Publications.

Details

- Pages

- 1104

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631854372

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631854389

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631854396

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631839225

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18405

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (August)

- Keywords

- urban planning urban design landscape design ecology environment-sustainability

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 1104 pp., 400 fig. b/w, 141 tables.