Communication Audit in Globally Integrated R«U38»D Project Teams

A Linguistic Perspective

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Frameworks

- Aim(s) and Research Questions

- Research Process & Design

- Structure of the Book and Demarcation of Chapters

- Part One: Thinking about Communication Audit

- Chapter 1: An Introduction into Communication Audit

- 1.0 Opening Remarks

- 1.1 Audit—General Considerations

- 1.2 Communication in Business: Models and Research

- 1.3 Communication Audit—Overview of Research Literature

- 1.3.1 Overview of Definitions of Communication Audit

- 1.3.2 Historical Background of Organisational Communication Audits

- 1.3.3 State of the Art

- 1.4 Closing Remarks

- Chapter 2: Criticism and Shortcomings of Communication Audit Definitions and Process

- 2.0 Opening Remarks

- 2.1 Definitions’ Shortcomings

- 2.2 Controversial and Contradictory Assumptions around the Communication Audit Process

- 2.3 Closing Remarks

- Chapter 3: Linguistic Approach to Communication Audits

- 3.0 Opening Remarks

- 3.1 Definition and Scope of Communication Audits

- 3.2 Process of Communication Audits

- 3.3 Methodology of Communication Audits

- 3.3.1 Approaches to Discourse Analysis

- 3.3.2 Anthropocentric Linguistics

- 3.3.2.1 Ethnographic Approach

- 3.3.2.2 Corpus-Based Approach

- 3.3.2.3 Discourse Linguistic Multi-Layered Analysis

- 3.4 Closing Remarks

- Part Two: Understanding Communication within Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams

- Chapter 4: Research and Development Projects

- 4.0 Opening Remarks

- 4.1 From Organisations and Corporations to Globally Integrated Enterprises

- 4.1.1 Groups

- 4.1.2 Project Teams

- 4.1.2.1 Projects

- 4.1.2.2 Project Management: The Traditional Approach

- 4.1.2.3 Project Team Members and Project Managers

- 4.2 Global R&D Project Management

- 4.2.1 Research and Development Activities

- 4.2.2 Project Management in Research and Development: Towards Agile Project Management

- 4.2.3 R&D Project Teams

- 4.2.3.1 Communication in R&D Project Teams: General Considerations

- 4.2.3.2 Composition of R&D Project Teams

- 4.2.3.3 Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams

- 4.3 Closing Remarks

- Chapter 5: Intercultural Encounters and Specialist Knowledge Transference in Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams

- 5.0 Opening Remarks

- 5.1 Intercultural and Interlingual Business Communication and Specialist Knowledge Transference

- 5.2 Discourse Communities or Communities of Practice?

- 5.3 Knowledge-Based Discourse Communities

- 5.3.1 Types of Knowledge

- 5.3.2 Specialist Cultural Knowledge Development: Learning

- 5.4 Culture and Language in Intercultural and Interlingual Business Communication

- 5.4.1 Cultural Aspects of Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams: Team Culture

- 5.4.2 Linguistic Interactions in Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams: Team Language

- 5.4.3 Discursive Competence as Part of Professional Expertise in Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams

- 5.5 Closing Remarks

- Chapter 6: Discursive Situations in Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams

- 6.0 Opening Remarks

- 6.1 Discursive Events

- 6.1.1 Email Chains

- 6.1.2 Project Meetings

- 6.2 Discursive Acts

- 6.2.1 Discursive Acts in Emails

- 6.2.2 Discursive Acts in Project Meetings

- 6.3 Closing Remarks

- Part Three: Towards a Communication Audit Model and Communication Audit Procedures in Globally Integrated R&D Project Teams

- Chapter 7: Communication Audit Research Process

- 7.0 Opening Remarks

- 7.1 Communication Audit Research: Introductory Remarks

- 7.1.1 Research Design: Multiple Case Study

- 7.1.2 Multiple Triangulation

- 7.1.2.1 Investigator Triangulation

- 7.1.2.2 Theory Triangulation: Theoretical Framework

- 7.1.2.3 Data Triangulation

- 7.1.2.4 Triangulation of Methods

- 7.2 Research Process

- 7.2.1 Preliminary Steps

- 7.2.2 Main Study

- 7.2.2.1 Organisation of the Main Study: Stages

- 7.2.2.2 Data Elicitation and Data Analysis

- 7.3 Closing Remarks

- Chapter 8: Research Results

- 8.0 Opening Remarks

- 8.1 Findings from the Communication Audits

- 8.1.1 Intercultural Issues

- 8.1.2 Linguistic Issues

- 8.1.3 Organisational Aspects

- 8.1.4 Technical Aspects

- 8.2 Findings Concerning Communication Audit Research Process & General Research Lessons Learnt

- 8.2.1 Dual Role of the Linguist

- 8.2.2 Difficulties, Limitations, and Challenges Encountered. Researcher’s Considerations

- 8.3 Closing Remarks

- Chapter 9: Communication Audit Model and Procedures

- 9.0 Opening Remarks

- 9.1 Communication Audit Model

- 9.2 Communication Audit Procedures

- 9.3 Closing Remarks

- Part Four: Application, Future Research, & Conclusions

- Chapter 10: Applications of Communication Audit Theory and Results

- 10.0 Opening Remarks

- 10.1 Application of Communication Audit Model, Communication Audit Procedures & Linguistic Form Sheet

- 10.2 Application of Communication Audit Results

- Chapter 11: Future Research Concerning Communication Audits

- Chapter 12: Concluding Thoughts

- Bibliography

- Books and Articles

- Dictionaries

- Internet Sources

| BELF | English as Business Lingua Franca |

| CALD | Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary |

| CED | Collins English Dictionary |

| CEDEL | A Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language |

| CofP | community of practice |

| DWO | Dictionary of Word Origins |

| EFCOG | Energy Facility Contractors Group |

| ICA | International Communication Association |

| ICT | Information and Communication Technology |

| L1 | first language (native language/mother tongue) |

| LDCE | Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English |

| LLCE | Longman Lexicon of Contemporary English |

| MAP | Meta Agile Process Model |

| NNS | Non-Native Speaker |

| NS | Native Speaker |

| OALD | Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary |

| p. | page |

| PMBOK | A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge |

| pp. | pages |

| R&D | research and development |

The idea to start dealing with communication audits in professional environments and as a result write a book on the communication audit in globally integrated R&D project teams initially arrived during my intensive research into communication in global corporations that deliver projects (see Zając, 2013). This idea began to develop following a question about communication audits asked by the company’s executives who shared data with me during the time I was researching communication in global corporations. They had been reading that ‘[c]ommunication audits can make a major contribution to organizational success’ (Tourish & Hargie, 2009c, p. 242), and they were interested in conducting a communication audit in their own company. Yet, they did not know how to organise a communication audit and what needed to be prepared. They thought an applied linguist would be able to help.

Furthermore, in the course of my research into business email communication, I became convinced that nowadays, with the enormous similarities between companies’ products and services, it is communication that makes it possible for customers to differentiate between companies and their offer. According to the slogan: ‘good (effective) communication makes a difference!’ It also became of interest to me how such professional communication can be assessed (the so-called ‘communication audit’) and later on controlled and managed on a regular basis, for instance in the form of the ‘continuous communication audit’, (intercultural) communication trainings, workshops, and coaching. Communication audit methodology in general offers, or should offer as I observed in literature on the subject, a way to ‘measure’, ‘assess’, ‘manage’, and ‘control’ business email communication and professional communication.

These two reasons, one of which can be called external and related to my personal history (a request for advice from practitioners) and the other one internal (my own curiosity triggered by research findings and existing literature), motivated me to take on the research topic of the communication audit and look for further literature on the subject. To my surprise, I discovered that up to now publications on the communication audit have been delivered mainly by specialists across a range of fields excepting (applied) linguistics, even though it is (applied) linguists who focus on researching language and communication. What is more, researchers have conducted a discussion on the communication audit, focussing on communication audit methodology with practical reference only to certain fragmentary examples, the reason being that communication assessment operates in different ways depending on the type of organisations (see Downs & Adrian, 2004, pp. 18–19; Tourish & Hargie, 2009d, p. 401). Even though it is surely unnecessary to argue that organisations are vastly different in many respects, and it is impossible to measure their achievements using the same yardstick, as a linguist I could not accept that communication audit methodology should be employed solely to address the issue of employees’ job satisfaction. ← 17 | 18 →

I was interested in finding out more about the entire, detailed process of the communication audit, paying special attention to actual communication rather than to employees’ job satisfaction. Indeed, I began looking for certain communication audit procedures or a communication audit model, based on the linguistic toolkit, that could be applied to real-life situations. But my search drew a blank. Thus, I decided to attempt to develop communication audit procedures and/or a communication audit model. In other words, the search for communication audit procedures and/or a communication audit model from the point of view of (applied) linguistics became my research purpose. However, I noted very early on that in order to develop such procedures or such a model, I needed to take into account various research perspectives. I present them in this volume after thoroughly acquainting myself with the theoretical assumptions on professional communication in business settings available in research literature, and with experience gathered from communication audits conducted mainly in what I call ‘globally integrated R&D project teams’. However, I focus only on R&D project teams formed in the business world, i.e. in global companies that were eager to introduce their processes to me and share data. In this book, I do not refer to R&D project teams in the academic sphere. Yet, I am convinced that such teams, as well as employers and employees in other institutions may profit from the findings presented in this book.

The discussion presented in this book is, on the one hand, general in nature as it refers to existing sources of information about the communication audit and strives to present communication audit procedures and a communication audit model applicable in a variety of contexts. On the other hand, it is detailed, describing as it does the whole (literally from A to Z) communication audit process in a globally integrated R&D project team precisely, and focusing on the methodology of communication audits from the point of view of applied linguistics. As a result, research undertaken for the purpose of developing a communication audit model is qualitative in nature. Its aim is to use the existing theoretical concepts to empirically investigate particular situations, and then from the results derived from these particular case studies to generate a theory, or at least a theoret1 (see Eisner, 2001, p. 141).

Global corporations and R&D project teams constitute a good choice for exploring the communication audit because they are international not only by name but also by nature. As a consequence of globalisation, the deterritorialisation of companies and hybridisation of cultures, i.e. a growing number of interactions between representatives of various cultures and their mutual influence, can be noted. This, in turn, implies that employees of global corporations extensively rely on communication, which has been more and more considered and its value stressed by numerous researchers and practitioners in recent years. With regard to R&D activities ever more frequently performed in the form of projects across national and cultural ← 18 | 19 → borders within the constraints of global corporations, the role of communication becomes of paramount importance.

I found dealing with communication audits in business settings to be interesting for one more reason. Namely, a communication audit offers the opportunity to combine theory with practice. It is of great significance to me to be able to be simultaneously active in both fields, i.e. to implement the theoretical deliberations in the empirical studies, as well as to draw conclusions from the practical work and transfer them into theoretical models:

It [= the communication audit—J.A.] provides opportunities for communication scholars to collaborate with organisational practitioners—to learn from practice and to act as facilitators, mentors, and coaches.

(Jones, 2002, p. 467)

Even though being in close proximity to practice has become increasingly attractive to scholars in recent years, enabling them to get a first-hand sense of what actually goes on in ‘the real world’, it carries certain dangers and risks, too (Eisner, 2001, p. 137). Amongst others, qualitative research undertaken close to practice takes a lot of time, as the researcher needs to be on site in order to understand what is going on there. Furthermore, fieldwork may take unexpected turns, which requires a great deal of flexibility and readiness to introduce modifications to the research design throughout the research process, thus consuming additional time. I will revisit these issues in the course of the book. Despite numerous inconveniences and difficulties related to qualitative research, I truly believe that such an approach to the communication audit and ‘the communication audit assignment [itself] can have long-term rewards for those who work within organizations, as well as for external consultants’ (Shelby & Reinsch, 1996, p. 95; see also Hart, Vroman, & Stulz, 2015, p. 304).

I hope with this book I can generate in at least a few people an interest in corporate communication assessment, and popularise the communication audit process amongst both scholars and lay people (not only corporation representatives). In particular, this monograph, I hope, will be of some interest not only for (applied) linguists, ethnographers, teachers of English, students, but also to HR specialists, managers, and those practising intercultural communication in everyday business context.

This book deals with aspects of communication audits from the viewpoint of applied linguistics. Even though the meaning and use of the term ‘applied linguistics’ is subject to heated discussion and controversy (see for example the points regarding the division between ‘pure’ and ‘applied’ linguistics as well as ‘theoretically applied’ vs. ‘practically applied’ linguistics in Knapp and Antos, 2009), I consider the linguistic concepts to be the point of departure and focal point of my research focusing on ← 19 | 20 → communication audits in intercultural business settings. During the execution of the research project, I further modify and develop the linguistic concepts, and supplement them with paradigms from other fields of study, depending on the needs of the professional settings in which communication audits take place (see Roth & Spiegel, 2013, p. 7). Similarly to Knapp and Antos (2009, pp. xi–xii), I am of the opinion that applied linguistics begins with the assumption that human language and human communication is imperfect. This applies both to individuals and groups of people, and to their linguistic and communicative/discursive competences. These imperfections of individual and collective language and communication continue to reoccur in a changing society and can be clarified and to a certain extent resolved by way of various interventions, such as training sessions, education, coaching, consultancy, etc. as proposed by applied linguists (see Crystal, 2004, p. 385). The process of clarification precedes enquiry and/or observation that is ethnographic in nature. Enquiry and observation can take different forms. The communication audit is one of them. It can help to develop appropriate language and communication training programmes, and consultancy/coaching sessions.

Nevertheless, issues related to language and communication apply across various scopes of reality, and therefore require a trans-disciplinary approach. Taking a multidisciplinary perspective is particularly recommended when communication is conducted in an international setting (e.g. Lüsebrink, 2004, pp. 12–13), i.e. when people representing various cultures and having various L1s (mother tongues) communicate2 with an attempt to reach certain goals:

Due to its interdisciplinary character, intercultural communication seeks inspiration by theories, models, methods and critique from various corners of the social sciences, cultural studies, humanities and education.

(Otten et al., 2009, online)

Indeed, in light of examining interactions between specialists of different cultural and linguistic backgrounds interacting in a lingua franca, or in one of the interlocutors’ language, within the constraints of the communication audit, it is worth taking an interactive intercultural approach (see Clyne, 1994, p. 3), which combined with ← 20 | 21 → a multidisciplinary perspective can bring valuable results. For this reason, when describing the frameworks of communication in globally integrated R&D project teams, I supplement the theories and models developed by linguists and applied linguists, especially as regards linguistic discourse analysis, with the insights delivered by other disciplines, in particular project management, intercultural communication, psychology, sociology, ethnography. This is the so-called ‘another set of values … the range of non-linguistic factors that underlay the problem’ (Crystal, 2004, p. 385), also stressed by other linguists, amongst them being Clyne (1994, p. 5), Ewald, Schröder, and Tiittula (1991, pp. 96–97). I believe that the benefits of interdisciplinary dialogues, in particular in an intercultural context, can lead to a broader and hence better understanding of the communicative reality investigated. In fact, there are numerous examples of successful interdisciplinary collaboration. At the same time, paradoxically, it turns out that there are often overlaps in approaches, methods, and theories, which have been proposed by researchers representing various fields, and can be brought to light in interdisciplinary dialogues. In this book, it will be noticeable that these overlaps are masked merely by different names in different fields. However, it is not overlaps in approaches, methods, and theories developed within different fields that are of great interest here, but it is the possibilities of complementing applied linguistic research with theories of other disciplines that are of paramount importance for a better understanding of the communication audit. In this way, the potential of various theoretical constructs and research methods can be exploited. In order to obtain a broad enough picture of communication audits in globally integrated R&D project teams, I will also use a combination of data types.

In summary, the trigger for this study lies in practical linguistic and communicative problems, which I attempt to define and describe against the background of theoretical and methodological paradigms developed mainly by applied linguists, but also by researchers representing other disciplines. I study the addressed issues in order to develop certain suggestions for solutions. The ultimate objective of this study is to develop communication audit procedures and a communication audit model that can be further utilised by both researchers and practitioners who are interested in communication.

Broadly speaking, the theoretical objective of the book is to increase the understanding of communication audits, their process and methodology, whilst the applied objective is to improve the quality of communication audits and to enhance the application of their results to further communication training sessions, seminars, and programmes. Communication audit methodology and process will be explained based on communication in international business settings. More specifically, this monograph is based on an interactive intercultural study of workplace communication of professionals from diverse backgrounds, mainly German and Polish, using English as a lingua franca. ← 21 | 22 →

In the course of the research process (see below and Chapter 7), I posed the following research questions:

- What is a communication audit from a linguistic point of view? What are its aims? How can it be defined?

- What is the scope of a communication audit?

- What does a communication audit process look like? What are the phases of a communication audit from a linguistic point of view?

- Which (linguistic) methods can be applied to conduct a communication audit?

- What do R&D activities imply?

- How are R&D project teams organised in an international business environment and what principles do they apply in practice?

- How much communication do R&D activities involve?

- How should a communication audit be organised? What steps does a communication auditor need to take when working together with a globally integrated R&D project team?

- Can a communication audit model or communication audit procedures be developed? If yes, what are the elements/components of such a model/such procedures?

Throughout the book, I attempt to provide answers to these questions.

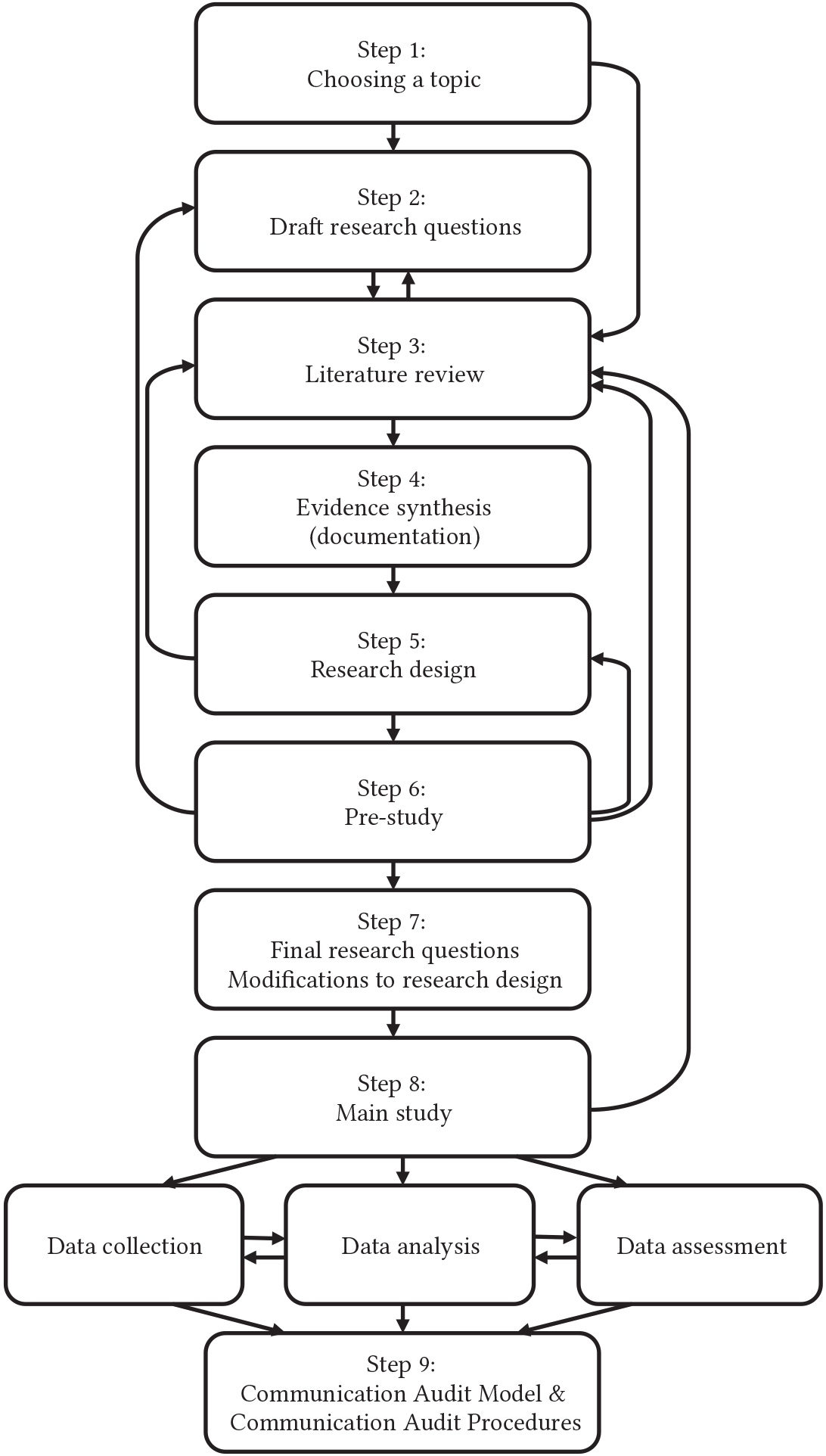

In order to develop a model and procedures of business communication audits in a systematic way, I applied a research process, which can be called a ‘progressive focusing model of the (qualitative) research process’ (see Sinkovics & Alfoldi, 2012, pp. 110–112). ‘Progressive focusing’ implies that research is qualitative as well as putting emphasis on pre-fieldwork preparation and openness to emergent issues. Thus, revisiting the adopted steps and concepts is part and parcel of the research process. Figure 0.1 depicts the steps of the adopted progressive focusing model of a qualitative research process. ← 22 | 23 →

Figure 0.1: A progressive focusing model of the qualitative research process.

As mentioned in the opening remarks of the Introduction, the research project discussed in this book was triggered by the results of my previous project on communication in international project teams (Step 1). The research results led to posing draft research questions about what a communication audit is and how it can be implemented in global settings (Step 2). This, in turn, implied reviewing research literature, considering existing empirical evidence and theoretical/conceptual foundations (Step 3). This step ended with the synthesis of what has been achieved to date in the field of communication audits (Step 4) and the identification of research design (Step 5). Then, the preliminary research questions and research design were tested and reviewed during a pre-study (Step 6) and subsequently re-formulated (Step 7). The pre-study also helped to test the data collection methods chosen for the main study. Next, the main study was conducted (Step 8) which consisted of data collection, data analysis, and data assessment. Developing communication audit procedures and a communication audit model (Step 9) was the final step of the research process.

The research design took the form of case studies in four groups (Polish-German R&D project teams), to which a rather flexible approach was adopted. In other words, it was accepted that research design, methodology, and questions may evolve as a project unfolds (see arrows going in various directions between some research process steps and arrows on the right- and left-hand side in Figure 0.1). Due to the fact that the communication audits were undertaken in companies on the basis of non-disclosure agreements, their details cannot be revealed. It should also be explicitly pointed out that during the communication audit process highly sensitive data is collected, which requires full data anonymisation. Nevertheless, in the course of the discussion I present short masked examples that will hopefully make it easier for the reader to understand ideas with regard to the communication audit process, in addition to the model and procedures of communication audit proposed in this book. The detailed description of the research process steps and research design is provided in Part Three of the book.

Here, as a linguist, I would like to complement the above considerations on research process and research design with a few remarks on my own approach to conducting research. For many researchers in linguistics these might be obvious (see e.g. Brühler, 1934/1982, pp. 12–24), though they may also spark some controversy. However, I consider these aspects of the utmost importance to undertaking qualitative linguistic research, in particular with regard to communication audits in business settings, and hence I would like to stress them at the outset of this volume:

(1) Linguistic research is based on observations. The word ‘observations’ refers here to a direct observation in vivo, to written documents, and to recordings. This means that the linguistic enquiry inevitably encompasses ethnographic elements. ← 24 | 25 →

(2) Research ideas are related to the personal history of the researcher and to the experiences that the researcher has collected:

Daß alle unsere Erkenntnis mit der Erfahrung anfange, daran ist gar kein Zweifel: denn wodurch sollte das Erkenntnisvermögen sonst erweckt werden.

(Brühler, 1934/1982, p. 14)

This implies that the scholar begins his/her research tasks and also enters the field with certain theories in place. In this sense, developing a ‘grounded theory’ is, in my opinion, nigh impossible.

Details

- Pages

- 405

- Year

- 2016

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653061017

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653961317

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653961300

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631666609

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-06101-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (April)

- Keywords

- business email linguistic form knowledge transfer(ence) project meeting

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2016. 405 pp., 68 b/w ill., 10 tables