The Long Shadow of Don Quixote

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Quixotism

- 1. From the Proper Name to a Common Noun

- 2. The Culture-Studies Perspective

- 3. Don Quixote as a Symbol

- 4. Mundo Quijotesco as a Space of Values

- 5. Homo Culturalis

- 5.1 Subjectivity Turn

- 5.2 “I Know Who I Am!”

- 5.3 Axiocentricity of Madness

- 5.4 Dialogue as a Spiritual Exercise

- 5.5 Performance: Action that Transforms the World

- 5.6 Second Birth in Culture

- 6. Axiotic Topography of Quixotism: An Example of Justice

- Chapter Two: Research Tools: Between the Reader, the Book and the World

- 1. Testaments and Styles of Don Quixote’s Reception: Literary-Theoretical Inspirations

- 2. Literary Culture: The Axiotic Potential of Literature

- 3. Imitation: “Triangular” Desire

- 4. Don Quixote as a Paradigmatic Figure: On Identification with a Literary Character

- 5. Literary Characters “More Real than Real Life Itself”

- Chapter Three: The Names of Don Quixote

- 1. (Self-)Descriptions

- 2. Adventures

- 2.1 Manias and Their Kinds

- 2.2 The Uses of Don Quixote

- 2.3 Invectives

- 3. Ideas and Ideologies

- 3.1 Revolutionary Devils

- 3.2 Don Quixotes of the Generation of ’

- 3.3 Don Quixotes of Polish Politics

- Chapter Four: Bibliomania: The Adventure of Reading

- 1. Don Quixote in the Age of Reading

- 2. Don Quixote as a Reader Par Excellence

- 3. Transcriptions

- 4. Cases of Bibliomania

- 4.1 Spiritual Exercises

- 4.1.1 Ignacio Loyola’s “Middle of Life”

- 4.1.2 The Order of Books: Saint Teresa

- 4.2 Idealisation of Love: Cut-Throat Books

- 4.2.1 Sentimentalism

- 4.2.2 Romanticism

- 4.2.3 Bovarism

- 4.3 The Republic of Dreams

- 4.4 Cristoforo Colombo: Chasing Adventure

- 5. Bibliomania: Between Fugis Mundi and the Great Theatre of the World

- Chapter Five: Quixotism and Evil

- 1. Madness of Violence

- 2. On the Harmfulness of Good Fellows

- 2.1 “Menace of an Idiot”: Prince Muishkin

- 2.2 Contagious Quixotism

- 2.3 Monster or Devil? The Demonic Yurodivy

- 3. Is It Possible to Read Don Quixote After Auschwitz? Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones

- 3.1 “Books, the Causes of Evil”

- 3.2 Maximilian Aue: “A Doleful Knight with the Broken Head”

- 4. Saint or Soldier?

- 4.1 Ignacio Loyola

- 4.2 Santiago Matamoros: The (Re)Conquista

- 5. The Apology of Don Quixote

- Conclusion

- List of Illustrations

- Selected Bibliography

In the second part of Miguel de Cervantes’s novel The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote de La Mancha published in 1615, clever bachelor Samson Carrasco opines: “It is evident to me that every language or nation will have its translation of the book.”1 It was only ten years earlier that the book’s first part was released by Juan de la Cuesta’s printing house in Madrid. The insight attests to Carrasco’s brilliant prognostication skills: reportedly, the novel has had 2,500 editions in no fewer than 70 different languages so far. The extraordinarily opulent literature on Don Quixote makes it the world’s most discussed novel.2

The works of literature that have proven inspirational to the largest number of readers have been labelled “great” by Richard Rorty. Thus conceived, the greatness of Don Quixote has produced remarkable manifestations and implications throughout the history of culture and the study of culture. Translated nearly instantaneously into other European languages,3 Don Quixote soon broke loose from its original socio-historical context and became an object of culture in its own right. The transfiguration of the literary character into a mythical and symbolic ← 9 | 10 → one was precipitated by the alchemy of mass popularity, but that alone does not explain the cultural phenomenon we confront in Don Quixote. This phenomenon – the long shadow cast by Don Quixote, to use Vladimir Nabokov’s metaphor – is notoriously difficult to account for. “It seems as if a literary work has started to live a life of its own,”4 writes Fernando Pérez-Borbujo, who sees the ultimate autonomy of Don Quixote in the protagonist’s eventual parting from Cervantes and in the novel being reputed by “all nations” as a unique “historical chronicle.” What does all this mean? It means that “it does not strike anybody as odd now that so many people know Don Quixote without actually knowing that it was authored by Cervantes.”5 At the same time, the knight’s fortunes and misfortunes are so ubiquitously familiar that they are located in the realm of the myth rather than believed to be a product of the literary imagination.

Illustration 1: A bookshop in Santiago de Chile, photo M. Barbaruk

As early as in 1925, Américo Castro wrote in “El pensamiento de Cervantes,” by now a classic text of modern criticism: “Everything, or at least nearly everything, has already been said about Cervantes.”6 A 2008 bibliography of studies on Don Quixote and Cervantes, though including publications in seven languages only, lists about 14,000 entries and took fifteen years to compile.7 Without doubt, the problem of Don Quixote is one of those whose magnitude overwhelms and which have engendered an intimidating wealth of varied commentaries. And yet, impossible though it may seem, studies on the cultural dimension of Cervantes’s legacy are scarce, if not altogether non-existent. This, however, is not the primary reason for the task I set for myself. My major impulse was provided by the fact that the contemporary humanities seemed so profoundly and extensively engrossed with the knight-errant that the very fascination called for an in-depth interpretation. My goal, thus, was to find out the reasons for Don Quixote’s unmistakable return, to reflect on the contemporary “uses” of the figure and to establish whether these uses are similar or different, whether they diverge from the prior ones and, if so, whether that change is symptomatic – that is, whether it is entwined with transformations of and in culture. The design seemed promising as it offered an opportunity to capture not only the condition of the humanities but also the condition of culture as such.

Of course, faced with a plethora of studies that define themselves as culture-oriented, we need to remember that the argument in this book subscribes to a certain model and has its distinct provenance; namely, it is underpinned by the theoretical framework developed in kulturoznawstwo, a specifically Polish variety of cultural studies initiated by Wrocław-based culture scholar Stanisław Pietraszko in 1972, which I henceforth will refer to as culture studies.8 Out of ← 11 | 12 → the copious reception of and research on the novel – the output of philosophers, writers and critics, whom Miguel de Unamuno groups in two categories of “Cervantists” and “Quixotists” – I am interested here in what Quixotism reveals when scrutinised through a lens that focuses on culture in its specificity – that is, from a value-oriented perspective. Of course, this delimits Quixotism; instead of a varied entirety of meanings this notion commonly designates, Quixotism as defined in these terms is an axiotic space demarcated by its distinct values – it is a type or a dimension of culture. As such, it can be referred to as axiological Quixotism. Quixotism is, thus, an actually existing order of the human universe externalised in various forms and shapes throughout history. This being so, I could declare, together with José Ortega y Gasset, that “my Quixotism has nothing to do with the merchandise displayed under such a name in the market.”9

Quixotism (donkichotyzm in Polish) as a literary-critical term appeared in Poland in the 19th century. It quickly became common currency and still continues to be a useful descriptive tool principally in literary studies. In the recent Polish publications, Don Quixote tends to be viewed as a structural and generic model for other novels while Quixotism sometimes denotes absorption of the Spanish protagonist by other novelistic traditions.10 In the Spanish research, initiated by what came to be known as the Generation of ’98, Quixotism, as a notion and a term, is discussed first of all in the psychosocial context, for instance, in the fundamental national myth of the “Spanish mentality” or “essential Spanishness” (expressed in such concepts as hidalguía, espaňolidad, hispanidad, casticismo). In this sense, Quixotism is more closely aligned with the perspective I adopt in this book since it abandons “the reality of the text” and exposes the human reality of culture. To clarify, my interest in the texts which link Quixotism to Spanishness neither articulates a theoretical position which sees culture as bound with a particular nation nor signals an inclination to focus on a specific, nation-centred reading of the novel.

Integral to my thinking about Quixotism as recounted in this book was the question of what values must inform one’s being if it is to qualify as an instance of Quixotism. Consequently, the outlining of Quixotism’s axiotic space defined by its ← 12 | 13 → essential “coordinates” – i.e. values – involved attempts at sketching Don Quixote’s cultural description or biography. An inquiry into values as the main reason for and the criterion of interest in certain empirical material, while perhaps not a very handy tool, promises to open up attractive cognitive vistas. I believe that it effectively offers an opportunity comprehensively to examine the changing fates of Don Quixote in culture, to trace his various incarnations also prior to 160511 and to approach these various phenomena and developments as expressions of the culture of Quixotism founded on a specific set of values. I looked for incarnations of Don Quixote in texts which interpret and re-interpret the knight-errant in a variety of ways and in works which do not take Cervantes’s hero on board but feature characters that earn the moniker of Don Quixote. I also put my own hypotheses to the test, suspecting that the ideas that had come to my mind had actually been already formulated elsewhere without me knowing the literature sufficiently to have come across them earlier. Among the populous throng of Don Quixotes in this book, the most important – and hence the most systematically explored – ones are St. Teresa of Jesus, St. Ignacio Loyola, St. James, Columbus, Cyprian K. Norwid, Thomas Mann, Adam Michnik and literary characters such as Sophie, Gustaw, Emma Bovary, Stanisław Wokulski, Jewish traveller Benjamin the Third, Prince Muishkin and SS man Maximilian von Aue. My research practice, so extensively relying on literary fictions, is informed by the notion that literature is “a statement about values” and “not only a reflexion but also a fulcrum of values.”12

Don Quixotes are to be found among readers who stepped out of the library to take up action, putting what they have read in books into practice. Whether rendered literally or metaphorically, this circumstance is perhaps the most important distinctive index of Quixotism in the human world. And this book is largely devoted to analysing particular instances which showcase “the workings of literature in the human world.”13 Such operations are predicated upon interrelatedness of literature and culture, which is far less obvious than the popular ← 13 | 14 → opinion would have it. The literature-culture interconnections can be grasped only when the category of literary culture is conceptualised in a non-philological framework. In the culture-studies perspective, literary culture denotes “a network of unique, literature-mediated relations of humans and values.”14 The goal of literary culture, like of culture in general, is “to instil values.”15 Symptomatically, exploring the axiotic potential of literature, we tend to define literature reductively as a form in which culture is realised. The concept of literary culture may not be useful in studying all aspects of Quixotism and the entire tradition of Don Quixote, but it is certainly functional when a literary work (for example, Cervantes’s novel) can be attributed with stirring, directly or indirectly, human subjects, real or literary, to action.

Much has been written about the interpretations of Don Quixote we have inherited from the 17th century, the Enlightenment and, in particular, Romanticism. One may easily skip the original publications as they are summarised in commonly available primers, even very modest ones. Nearly a hundred years ago, Michał Sobeski construed Quixotism (kiszotyzm in his rendering) as a version of American pragmatic philosophy developed by William James, which was growing in popularity at the time.16 In his Na marginesie Don Kiszota (About Don Quixote), Sobeski observed that, a hundred years before, the Romantics had done exactly the same thing, proclaiming “Don Quixote an artistic equivalent of philosophy flourishing in their day.”17 Sobeski firmly believed that the history of interpretations of Cervantes’s brilliant novel was far from over as the book, “into which so many sundry things have already been inserted, still makes room for quite divergent philosophical systems.”18 And indeed, the 20th century (its second part in particular) thoroughly outdid the preceding one in terms of the sheer volume of critical studies and the diversity of their methods and approaches. As a result, no human being can possibly read everything that has been written about the novel. Don Quixote’s adventure has been outdistanced by the adventure of the literary work, to paraphrase the title of a book by Polish historian and theorist of literature Henryk Markiewicz.19 Recent readings of Don Quixote have not been comprehensively and synthetically described yet, one reason for this being ← 14 | 15 → that they require ever more wide-ranging competences. This lack is acutely felt because the recent interpretive developments concerning the novel – and, thus, changes in what sense is being made of Quixotism – are essential in filling the gap in the history of ideas as well as in studying the identity of our culture today. I believe that by examining the ebbs and tides of interest in the Spanish hero we can extrapolate certain dynamics of culture and outline its continuities and disruptions.

In his essay “Don Quijote, el hijo intrato de Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra,” Michel Tournier states that as the tenth or twentieth generation of readers of The Sorrows of Young Werther or Madame Bovary, we are virtually unable to distinguish what the author/s wrote from what was superimposed on that raw texture in the first, second, third and umpteenth reading. In this book, I do not aspire to fill in the lacunae in the interpretive history of Don Quixote, but I do seek to identify the distinctive aspects of contemporary meanings invested in the knight-errant.

In an essay written in 1945, Pedro Salinas, a member of the Spanish Generation of ’27, analysed the status Cervantes’s novel enjoyed at the time and considered it “a classic.” Functionally defined, a classic is a book which always “does the highest quality favour” to people.20 Such a work is, in his opinion, typically capable of asserting its weight and relevance at all times. It places an injunction on the reader to be responsible in thinking and experiencing that which transcends quotidian life. “Its revealing and illuminating value never ceases.”21 Given this, Salinas asks what it is that Don Quixote illuminates now: “What purpose does it serve in this year of 1945, the year of happiness and misery? Does Don Quixote carry any important message for contemporary people?”22 Like many other readers and researchers of the novel, Salinas points out how enlightening it is to locate the novel in subsequent epochs and insists that, accruing ever new meanings in time, it cannot be fully encapsulated in any ultimate interpretation. Well, my ambition in this book is exactly opposite. Rather than elucidating the novel (through the changing world), I intend to illuminate the human world – culture, to be more precise (through the changing interpretations of the novel). My question, then, would be: What does Don Quixote denote today? What does it name in the human way of life? What truth about cultural reality is revealed in its recent “uses”? Can the uses invented by Eco, Foucault, Girard, Kundera, Agamben and Bauman ← 15 | 16 → be called post-modern? Is post-modernism “quintessential Quixotism” today? Certainly, the humanities view both Don Quixote and Don Quixote as a threshold of modernity. I believe that to devise a fitting, pithy label for the contemporary understanding of Quixotism is neither essential nor actually viable even though such attempts feature profusely in current Don Quixote scholarship and criticism. To explore values implicated in the study of the modern and post-modern condition of the knight-errant is an entirely different venture.

The notion that new interpretations and interpretive modes reveal salient changes in culture is encouraged by American literary theorist Derek Attridge, who asserts: “It is only through the accumulation of individual acts of reading and responding, in fact, that large cultural shifts occur, as the inventiveness of a particular work is registered by more and more participants in a particular field.”23 To my mind, the picture of the dynamics of culture Attridge sketches is rather simplified. At this point a disclaimer is in order: not all novel insights about Don Quixote are interesting to a culture scholar. Hence, in what follows I largely omit the semiotic framework inspired by the Russian studies as well as the structuralist, formalist and narratological approaches (therein important work done by the likes of Erich Auerbach, Jurij Lotman, Wiktor Szkłowski and Leo Spitzer). Surprisingly perhaps, I also choose not to dwell on feminist, gender, psychoanalytical and ethical readings.24

What I found cognitively promising was following in the footsteps of Unamuno, who suggested about a hundred years ago that the conquistadors, the Counter-Reformers and the mystics had all been steeped in Quixotism. This observation ← 16 | 17 → seemed to me to open up new signification fields of Quixotism. My next step was to trace other, sometimes controversial, comparisons and cross-references, such as Joanna Tokarska-Bakir’s reading of Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones, in which she calls the book’s protagonist – a German Nazi – a Don Quixote. How does it contribute to the notion of Quixotism? Apparently, the problem of evil pervading Quixotism and Cervantes’s novel as such, an issue targeted already by Enlightenment criticism, so disaffected with Don Quixote, and by a handful of later authors, is being articulated anew as an ethical turn in the humanities gathers momentum. Because such articulations are highly pertinent and meaningful, we need to ask what to make of Don Quixote in the post-Auschwitz world. We need to ask whether the knight, who seems to be Scheler’s “moral genius,” may in fact be a “devil incarnate.” Even if the way the Spanish Falangists used the Unamunean interpretation of Don Quixote in the wake of the Spanish civil war still seems an obvious case of overinterpretation and usurpation,25 in hindsight that dispute appears to herald the unveiling of Don Quixote’s devilish facet. Linking the knight to evil is, as such, hardly a stunning thesis given that Cervantes’s book eulogises the soldiering way of life.

Still, the insistence on scrutinising and capturing the latest interpretations of the novel and its protagonists should not overshadow another observation – namely, that in view of this book’s goals, the most important and cognitively fruitful findings are the sightings of Don Quixote on the peripheries of the mainstream criticism, out of his natural element. Crucially, he appears in texts which are not even tangentially related to the history, literature and culture of Spain or to travel reports of visitors to this country. “I thought that it was not a coincidence that my Great Authors – Greimas, Bakhtin, Lotman, Weinrich – had written on Don Quixote at one time or another in their lives,”26 writes Jorge Lozano ← 17 | 18 → in the preface to Asun Bernárde’s, Don Quijote, el lector por excelencia. Bold insights made in the contemporary humanities literature and, most frequently, on its margins were my signposts in exploring Quixotism and informed my choice of issues to be tackled in this book. As I was to discover, those not infrequently revolutionary interpretations were deeply indebted to other texts and kept bringing new titles into play. The exploration of the long and tangled intellectual paths that have made our current readings of Don Quixote as a devil, a monster or a Nazi legitimate was propped also by research subjectivity I endorsed. The analysis of the affinity of Quixotism and evil I present below sprung originally from a reader’s shock induced by Don Quixote,27 an impression that only later came to be corroborated when I found out that there were others – critics, writers, scholars and readers – who thought alike.

How to define the time-frame of interpretations and “uses” of Don Quixote to be examined? It seemed the most convenient solution to focus on contemporary humanist thought. The choice of contemporary, admittedly quite a nebulous notion, rather than of, let’s say, twentieth-century thought, or any moniker derived from the name of this or that framework regarded as the koiné of the humanities at the moment, was dictated by the fact that our current understanding of and thinking about Don Quixote are profoundly informed by century-old interpretations. The year 1905, which witnessed lavish celebrations of the three-hundredth anniversary of the publication of Don Quixote’s first part, was a turning point in the history of the novel’s interpretation. According to María C. Ruta, an Italian Cervantes scholar, it was a milestone of its “hermeneutical renewal.” It was then that Cervantes’s work was erected into a symbol of the Spanish essence and existence. The currently prominent concepts draw on the work of Miguel de Unamuno, a Spanish existentialist philosopher (whereby his insights are employed as the groundwork of knowledge on Cervantes’s protagonist rather than a component of history of “Don Quixote philosophy”). Given this, the year 1905, a year that saw the publication of Unamuno’s Vida de Don Quijote y Sancho, seems a good cut-off point, which obviously does not mean that all post-1905 interpretations qualify as relevant to or representative of our current ways of thinking. It was the Salamancan philosopher’s suggestive take on Quixotism that disseminated the romantic, “subjective” vision of the knight-errant and his squire so prevalent today. His romantic revaluing has enhanced the erasure of the parodic in Don Quixote ← 18 | 19 → and prompted the perceptions of the knight as a defender of sundry values which, though differently named, bear a strong affinity to each other.

The early 20th century is identified as the time of “an important shift” in the critical discourse on Don Quixote also by another Italian Cervantes scholar, Paola Laura Gorla. However, she pictures the genealogy of the shift in entirely different terms: “While earlier the critical attention had focused on the figure of Don Quixote himself, possibly in his relation to Sancho (as a comical supplement, a speculative reflection, an alter ego or a counterpoint), now it shifted onto the totality of the work, the dynamic interrelations of its two parts and, finally, the author himself.”28 As my interest does not lie in Cervantes himself and his masterpiece as such, the guiding spirit of my argument is Unamuno while the Italian scholar picks up the thread of Ortega y Gasset. I explore Quixotism of the character while Ortega is engrossed with “Quixotism” of Cervantes’s literary style. That is why I analyse only the texts which delve into what I call axiological Quixotism. Hence, I do not refer to the multiple meta-literary interpretations which argue that Cervantes was a post-modernist. Since “the work itself, heterogeneous and multidimensional as it is, (…) provides ample material for divergent analyses,”29 the corresponding spaces of Quixotism are capacious indeed. This affected my approach to the cases I selected – each time I sought to analyse a single aspect (e.g. bibliomania) rather than to produce an all-embracing account.30 Consequently, my analyses strove to identify values, or properties of values, that made it possible to recognise the culture of Quixotism in the material I had accumulated.

The object of research I delineated refers to what could be labelled the Don Quixote tradition in humanist thought. The category of tradition locates my research in an important context – the incommensurability of the work Miguel de Cervantes actually wrote and its contemporary status enmeshed in a variety of interpretations. Addressed since Unamuno’s days, the incommensurability is manifest in different forms, such as, for example, reiterated statements that Cervantes failed to understand Don Quixote, that Don Quixote now is an entirely different book from what it was in the 17th century, or that the novel’s protagonist is now far more real than Cervantes himself. The tradition, thus, does not entail petrification of the figure, the motif, the idea or the notion; on the contrary, it enunciates their vitality, openness and mutability. Crucially, the category of tradition helps ← 19 | 20 → steer clear of the diluted vocabulary bound up with the still fashionable notion of intertextuality. It seems, namely, that for my non-philological, cognitive purposes, what is quite commonly studied today in terms of intertextuality could be best approached in terms of tradition as a relevant axiotic mechanism of culture.31 I do not explore the Don Quixote tradition directly, but having this category in mind helps muster the meaningful, meta-theoretical reasons for studying the Cervantes hero, such as the intent to trace continuity of certain dimensions of culture and to show how certain axiotic spaces endure in time, constantly re-casting themselves in new images.

In 1884, Polish writer Bolesław Prus reflected on the profound significance of certain literary characters to the human sciences: “Such characters as Hamlet, Macbeth, Falstaff or Don Quixote are discoveries that count at least as much in psychology as the laws of planetary motion do in astronomy; Shakespeare’s value equals Kepler’s.”32 To paraphrase that, Cervantes is to psychology what Kepler is to physics. The psychological dimension of the Don Quixote figure33 is far more thoroughly researched than the cultural one. One problem with Don Quixote is that although innumerable studies, seminars and publications have investigated him (and still do), the humanities do not take him truly in earnest. “Is Don Quixote only a farce perchance?”34 wondered Hermann Cohen in Ethik des Reinen Willens. In their essentially cognitive reflection, the culture sciences tend to under-employ the knight-errant figure and concepts related to him although ← 20 | 21 → his uses are certainly becoming more and more pronounced.35 This book’s meta-theoretical purpose is, thus, to produce a synthesis of the history of culture through a scrutiny of axiotic spaces conjured up by various figures, symbols and myths.36 Its other purpose is tentatively to define the contemporary identity of the culture of Quixotism as well as to contribute to the methodology of culture studies and, more generally, the humanities dedicated to the study of culture. Using a literary character as a unique tool for analysing heterogeneous historical and literary material may be seen as an attempt on the part of culture studies to face up to the challenge of empirical research.

In his last Lecture at Harvard University, devoted to multiplicity in literature, Italo Calvino said: “Let us remember that the book many call the most complete introduction to the culture of our century is itself a novel: Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. It is not too much to say that the small, enclosed world of an alpine sanatorium is a starting point for all the threads that were destined to be followed by the maîtres à penser of the century: all the subjects under discussion today were heralded and reviewed there.”37 If the cognitive potential of The Magic Mountain is, in Calvino’s opinion, bound up with the 20th century, The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha leads us into a culture whose temporal boundaries are difficult to pinpoint. This encourages me to supplant The Magic Mountain with Don Quixote and “an alpine sanatorium” with the roads of La Mancha. Leafing through the 17th-century work, the reader can hardly resist the impression that Cervantes has anticipated virtually everything. Such must have been Zygmunt Bauman’s Don Quixote experience if he proclaims Cervantes “the founding father of humanities,” whose ground-breaking discoveries in the knowledge of human life have never slid into oblivion: “Cervantes was the first to ← 21 | 22 → accomplish what we all working in humanities try, with only mixed success and within our limited abilities (…) We all, in humanities, follow the trail which that great discovery laid open. It is thanks to Cervantes that we are here.”38

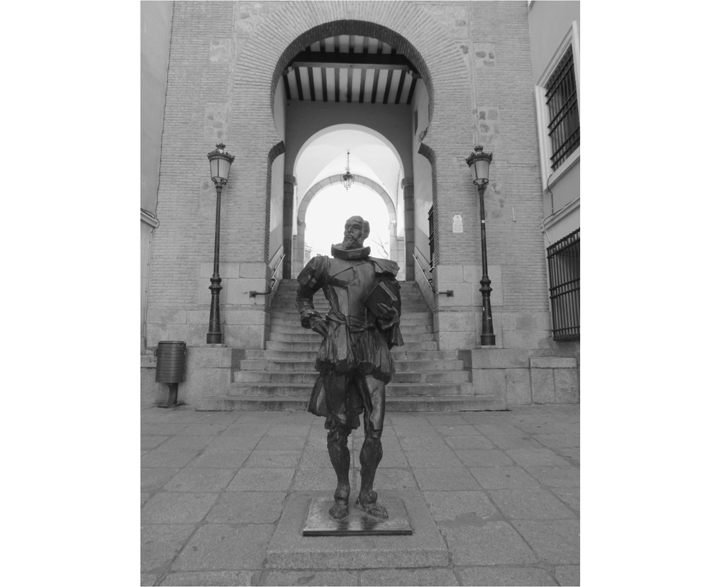

Illustration 2: A Miguel de Cervantes memorial, Toledo, photo M. Barbaruk

Alluding to the Book of Joshua, José Ortega y Gasset offers an insight that “[a] work as great as Quixote has to be taken like Jericho was taken.”39 To take Jericho, the Israelites had to march around the city several times.40 Before one ventures ← 22 | 23 → to outline the content of Quixotism, one must similarly circumnavigate it several times, in ever wider circles, giving it a multi-sided scrutiny and deliberate reflection. This book consists of five chapters, two of which are theoretical and methodological with the remaining three devoted to empirical analyses which reconstruct the axiotic spaces of Quixotism. First, Quixotism (donkichotyzm) is defined from the culture-studies perspective, whereby the differences from the meanings it has in literary studies and colloquial language are spelt out, and the humanities tradition is surveyed for approaches to Quixotism that approximate ways of thinking specific to culture-studies. I propose to treat the knight-errant as a patron of contemporary reflection on culture, in which culture is envisaged in terms of the Ciceronian metaphor of “the cultivation of the soul.” I also propose to include the notions of Quixotism and the culture of Quixotism into the terminology of the culture sciences.

The literary character and the notions it has instated may serve as tools to analyse varied literary and empirical material, but for that they certainly need solid theoretical grounding. In Chapter Two titled “Research Tools: Between the Reader, the Book and the World,” I present my “toolkit” – a set of instruments compiled as a methodological bricolage, characteristic of culture-studies research. I survey theoretical concepts and categories which seemed useful to my purposes and which are borrowed from other disciplines: literary studies, anthropology and psychology. Also, I attempt to operationalise the selected theories in which the knight serves as a model for explicating cultural reality (R. Girard, C. Castilla del Pino).

In Chapter Three titled “The Names of Don Quixote,” I demonstrate how the concept of Quixotism provides a vantage point on heterogeneous research material, a source of significant, but still inadequately examined, insights. I reflect on why certain characters, behaviours, gestures and situations may be referred to as “Quixotic.” I classify and describe the manifestations of the culture of Quixotism in the human world as addressed in criticism and more popular writings, and I interpret those which I find attractive for Quixotism studies but still largely unrecognised. The motifs that merit more analysis include, for example, the Quixotism of the Generation of ’68 portrayed in Paul Berman’s Power and the Idealists. A comprehensive survey of examples of Quixotism seemed necessary to me because I analyse genuinely in-depth only two of Quixotism’s many contexts: bibliomania and evil. In this book, I decided to show various shades ← 23 | 24 → of Quixotism using various examples, realising that one complex expression of Quixotism may serve to illustrate many themes.

Details

- Pages

- 288

- Year

- 2016

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653060324

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653961430

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653961423

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631666531

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-06032-4

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (December)

- Keywords

- Culture Values Humanities Quixotism

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2015. 288 pp., 16 b/w ill.