Balancing the World

Contemporary Maya "ajq’ijab" in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of contents

- Foreword by Håkan Rydving

- Preface

- A few notes on spelling and pronunciation

- Some commonly used words

- Part I

- Chapter 1 – What is an ajq’ij?

- Creating a project

- The ajq’ijab as presented by researchers

- What is an ajq’ij?

- Chapter 2 – Fieldwork in Guatemala

- Guatemala and the Maya

- Collecting data

- The interviewees

- Presenting data

- Fieldwork in Guatemala

- Part II

- Chapter 3 – Common terms

- Maya spirituality

- God and the sacred

- Ajq’ij and ajq’ijab

- Visitors

- Common terms

- Chapter 4 – The intermediary

- Important concepts

- Payment

- Christianity and Maya spirituality

- The intermediary

- Chapter 5 – Helping visitors

- Friends and strangers

- Why people visit

- Finding a solution

- Solving problems spiritually

- Helping visitors

- Chapter 6 – Gifts and burdens

- Non-visitor work – life and responsibilities

- Problems of practise

- Gifts and burdens

- Chapter 7 – The right person for the job

- Requirements

- Signs

- Inheritance

- The right person for the job

- Chapter 8 – Receiving

- Teresa

- Odilia

- Martin

- Carlos

- Receiving

- Part III

- Chapter 9 – Comparative contexts

- The context of similar research

- The context of categories within the study of religion

- The temporal context

- The context of one or several religious systems

- The context of tourism in contemporary Guatemala

- Comparative contexts

- Chapter 10 – Balancing the world

- Why does an ajq’ij do her or his work?

- How does an ajq’ij do her or his work?

- Why does one become an ajq’ij?

- How does one become an ajq’ij?

- Balancing the world

- References

← XII | XIII →A few notes on spelling and pronunciation

I occasionally use terms in Spanish, K’iche’ or Mam. If nothing else is specified, the term is Spanish. There are many differences from English when pronouncing Spanish words. This is far from a complete list, but these are maybe the most important differences:

In Guatemalan Spanish, ll is pronounced like y in yoghurt; j, and g in front of i or e, is pronounced like ch in loch or like a “strong h-sound”; and h is always silent.

When pronouncing K’iche’ or Mam terms, the ’ represents a glottal stop; x is pronounced like sh in shirt; ch is pronounced like ch in church; and j, like in Spanish, is pronounced like ch in loch. Nouns get the endings –ab or –ib in plural, but sometimes the interviewees used the Spanish ending –es for K’iche’ and Mam nouns as well, and so ajq’ijab and ajq’ijes are both used as plural for the term ajq’ij.

My spelling of K’iche’ terms is based on Allen J. Christenson’s unpublished K’iche’ – English dictionary.1← XIII | XIV →

_________________

1 Allen J. Christenson. “K’iche’ – English Dictionary” Accessed 22.07.2014. http://www.famsi.org/mayawriting/dictionary/christenson/quidic_complete.pdf.

← XIV | XV →Some commonly used words

abuelos (Spanish) – ‘ancestors,’ literally ‘grandparents.’

Ajaw/ajaw (K’iche’) – Usually translated as ‘owner,’ meaning ‘lord.’ Used to talk about ‘the spiritual breath,’ sometimes personified, by some of the K’iche interviewees.

ajq’ij (pl. ajq’ijab) (K’iche’/Mam) – ‘daykeeper.’

ajq’ijes (Spanish) – Spanish plural of ajq’ij.

mesa (Spanish) – ‘table.’ An ajq’ij’s altar, a sacred place or the role as an ajq’ij itself.

Tepeu and Gucumatz (K’iche’) - Tepeu: ‘King,’ ‘sovereign.’ Gucumatz: ‘Feathered snake,’ often seen as an equivalent to the Aztec deity Quetzalcoatl. The names are mentioned in the K’iche’ text Popol Vuh. Even though they use two names, the interviewees usually use both to talk about the same deity.

tzite (K’iche’) – Red seeds, often called “small beans.” Used by many ajq’ijab for divination.

vara (Spanish) – ‘staff (of office).’ Often used to refer to the role as an ajq’ij.

visitor (English) – A person who seeks the services, or work (see below), of an ajq’ij.

work (English) – trabajo (Spanish). Usually refers to the activities of an ajq’ij, such as performing ceremonies, divinations and counselling.

xukulem, mejlem (K’iche’) – ‘kneeling down, bending the knee’

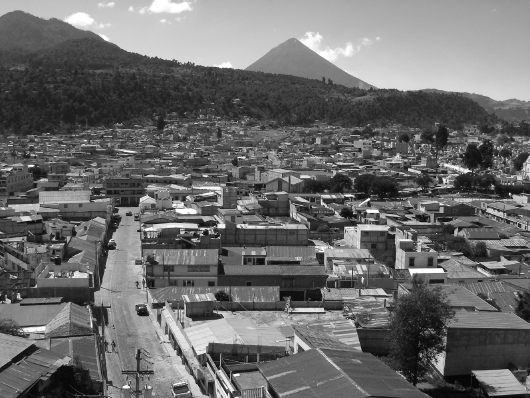

← XV | XVI →View of the outskirts of Quetzaltenango. The volcano in the background is Santa Maria, the biggest of the volcanoes surrounding the city.

← 2 | 3 →Chapter 1 – What is an ajq’ij?

Martin holds up two fingers and points. Throw two more into the fire, he signals to me, never breaking his swift stream of speech, a rapid, repeating pattern of words in Spanish and in the Mayan language K’iche’. “… poco de tiempo, un rato, una hora, una media hora,” ‘just a little while, just a moment, an hour, half an hour,’ he says again, like he has done several times already. He is talking to the ancestors, to God, to the universe and to everything, just asking for a little of their precious time. We are standing in front of a fireplace, and I put two more pieces of copal incense into the fire as I have been told. We are asking for blessings and permissions for the work we are about to begin.

There is a cross hanging on the wall above me. In the room we just left, there are more of them on a little house altar. For the ceremony, I brought fresh flowers which now bring colour to the little room in Martin’s backyard. There is also a picture on the wall; it shows Martin in front of a large group of people doing a ceremony.

“Close your eyes, this may sting a little,” he says, before he takes a swig from a bottle with a clear liquid. I do not realise what he means before the picture turns blurry and, not very surprisingly, my eyes sting. After spraying my face with alcohol, he proceeds to spray my neck and both sides of my head. I am now purified, ready to start my fieldwork.

Martin is what is known in several Mayan languages as an ajq’ij, a Maya “daykeeper.” The people in the picture, and the people that I talked to in the weeks after our ceremony, are ajq’ijab1 like him. Most of them live in or around Quetzaltenango, Guatemala’s second largest city. They practise Maya spirituality,2 and most of them are of Maya ethnicity themselves.

It is hard to pinpoint what an ajq’ij is. In Spanish, many of them call themselves guias espirituales, ‘spiritual guides.’ They have been called Maya priests, or diviners, or shamans, or witches. All of these terms imply something the ajq’ij is, or can be, from a certain viewpoint. They give a clue about the position of ajq’ijab in Maya communities, but these terms can also be misleading. I wanted ← 3 | 4 →to find out what the ajq’ijab themselves thought, and the result of my research is what is presented in this text.

Creating a project

I have been interested in Guatemala and the Maya for some years, and when I arrived in Quetzaltenango in August 2012, the city was not entirely new to me. I visited Guatemala for two weeks in 2006 as part of a cultural exchange project, and I went back for four months in 2008. During that visit I was part of the Norwegian Peace Corps, and although we were travelling a lot within the country, we regularly returned to Quetzaltenango.

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 140

- Year

- 2015

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653047103

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653980745

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653980738

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631654736

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-04710-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (September)

- Keywords

- Spiritualität Ritual Schamanen Vorfahren

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. XVI, 140 pp., 6 b/w fig.