Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Chapter I: Historical evolution of the state and political system of Switzerland

- I. The Old Swiss Confederacy: Origins, territorial expansion, religious wars

- II. The Helvetic Republic: The failed experiment to form a unitary state

- III. Restoration of the Confederation: Towards the modern Swiss state

- IV. The Federal Constitution of 1848

- V. Further development of the Swiss system of government

- VI. The Swiss Constitution of 2000

- Chapter II: How does Switzerland’s government function?

- I. Federal Assembly

- II. Federal Council

- III. Political parties and „the Magic formula“

- IV. The role of federal referendums and popular initiatives

- V. The Swiss Cantons: Diversity and unity

- VI. International assessment of the Swiss model for democracy and development

- Chapter III: The Swiss neutrality

- I. When and how did Switzerland become a neutral state?

- II. The Helvetic period and the subsequent international recognition of Switzerland’s neutrality

- III. Switzerland’s neutrality in the 19th and the early 20th century

- IV. Switzerland’s policy during World War I

- V. Switzerland and the League of Nations: From integral to differentiated neutrality

- VI. The Swiss independence and neutrality at stake during World War II

- VII. Switzerland and Nazi Germany: An inevitable compromise or an informal retreat of the Swiss neutrality?

- VIII. International critics of Switzerland’s policy during World War II

- Chapter IV: Switzerland’s foreign policy after World War II

- I. From international isolation to active neutrality

- II. Switzerland’s foreign policy after overcoming the division in Europe

- III. Historical evolution of neutrality in Europe

- IV. General and specific features of the neutrality of Switzerland and of other European states

- Instead of conclusion: Could the Swiss model be applied by other European countries (Bulgaria’s case)?

- Appendix

- List of references

- The Swiss model - The power of democracy (Summary)

While I was writing this book, I would often mention it in my conversations with other people and I discovered that everyone seemed to have the same notion of Switzerland as a synonym for a democratic and advanced country. They would give referendums and neutrality pride of place in the country’s “visiting card”. This view is perfectly correct. Referendums and neutrality are essential characteristics of what we could call the “Swiss model” for a state and political system of governance. It is underpinned by the same principles that are applied by the other democratic countries – political pluralism, rule of law, observance of the fundamental human rights and liberties, separation of powers, viable civil society. On the other hand, the “Swiss model” is distinctly specific in its own way. In terms of domestic policy this is chiefly manifested through the development of direct democracy efficiently complemented by representative democracy, while with respect to foreign policy its distinction derives from historical continuity and the role of the neutrality as a primary means for protecting the state sovereignty and asserting the national interests in the context of international relations.

The direct democracy and neutrality in foreign policy are not Swiss “patents”. To one extent or another they exist in a number of other states in and outside Europe. Yet, Switzerland is one of a kind. For more than a century and a half the Swiss citizens have participated directly and willingly in determining the most crucial issues concerning the national development and domestic and foreign policy which the country should pursue. This happens mainly through referendums which have long been perceived as the symbol of democracy in Switzerland. They play a mainstay role in keeping the unity of the confederation state made up of twenty-six cantons, each with a high degree of autonomy and different from the rest, three large language and cultural groups (German, French and Italian), two principal denominations (Catholic and Protestant), as well as immigrants who constitute a fourth of the population.

The potency of the Swiss state and political system stems from the fact that it was created and has been consistently evolving in line with the democratic values, the recognized need for national unity and the achievement of consent through dialogue and compromise in the name of the common goals and interests by fully acknowledging and executing the will of the majority of Swiss citizens. In this respect, the country has gone a long way historically before reaching its present condition. To establish a stable and efficient model of governance within a confederation type of state proved to be a tough process as the basic constituent entities – the cantons – vehemently defended their inde ← 11 | 12 → pendence and autonomy, and agreed reluctantly to vest the central government with broader powers. In addition to that, there was the negative effect of the interference by the big neighbouring countries. In the course of centuries upon the foundation of the Swiss state its territory was subject to recurrent conflicts. From the early 15th century till the mid-19th century, i.e. a period of four and a half centuries, the internal stand-off, especially on religious grounds, led to a number of major internal conflicts A turning point was reached only after the last civil war of 1847 and the subsequent adoption of the Federal Constitution a year later, which laid the foundations of the Swiss modern system of government and democracy.

Over the following decades the system was consistently improved, until it finally reached its present-day state. Modern Switzerland is constitutionally defined as confederation with due regard to the historically rooted understanding that it is a union of sovereign states (cantons) which retain their broad autonomy and independence. In fact, the system of government has gradually developed into a federal type of state. The underlying principle in the constitution guarantees that cantons are fully sovereign and can exercise all rights that are not delegated to the Confederation. It provides for substantial functions that are entrusted to the central government and a high degree of independence provided to cantons on the basis of distribution and combination of powers.

The constitution determines the civil and political rights and liberties in accordance with the fundamental international documents in this field: the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (European Convention on Human Rights) (1950), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), etc. The political rights are included in Swiss citizens’ fundamental rights and are linked with the social goals of the federal and cantonal authorities (access to social security, healthcare, assistance for families and persons against the economic consequences of old age, disability, illness, accident, unemployment, maternity, being orphaned and being widowed, etc.). In their entirety, the fundamental and political rights in the Federal Constitution together with the social goals substantiate the democratic nature of the Swiss state system. The basic text also stipulates the status, powers and rules regulating the main federal institutions: the Federal Assembly, Federal Council, Federal Administration, Federal Court, the forms and means of direct democracy.

The key instruments of direct democracy in Switzerland are the referendums. Swiss citizens have the right to use popular initiatives to propose new referendums on a variety of issues. Through the referendums, the Swiss citizens take direct participation in political decision making and respectively in the governance of the country in basically all spheres of national development and in ← 12 | 13 → implementing the country’s domestic and foreign policy. In this mechanism, through which the Swiss political system operates, the representative and direct democracy interact and balance out each other, ensuring the stability and efficiency of state governance. The referendums have long ago become an inseparable element of Switzerland’s public and political life. Between 1848 and 2013, i.e. in 165 years, a total of 593 federal referendums have been held. It is sure that the mark of 600 federal referendums will be reached on 18 May 2014. Until then new seven federal referendums are planned to be held. This makes an average of some three and a half referendums per year.

Neutrality is another fundamental element of the “Swiss model”. Before and even after establishing its neutrality Switzerland’s foreign and defence policy underwent a long period of evolution marked by contradictory signals and continuous adjustments to the fluctuating external environment. Over the course of several centuries after its coming into existence as a state in 1291, the Swiss confederation was involved in dozens of not only defensive but also conquest wars. Its geographical expansion was chiefly a result of the accession of new territories. The watershed moment came in 1516 upon the defeat of the Swiss mercenaries near Marignano (Melegnano) during the warfare in Italy. It was at that point when Switzerland started giving up its engagement in war conflicts and signed peace treaties with the neighbouring countries, thus turning into the first state in Europe that declared permanent neutrality. Switzerland’s permanent neutrality was internationally recognized in the Treaty of Vienna signed on 9 June 1815 and since then the country has never taken part in any war conflicts.

Switzerland’s neutrality is to a large extent conditioned by the principles on which the country’s political system is built, and on the pacifist leanings of the greater majority of the population. Its importance for the country is immense. It has allowed Switzerland to avoid the dangers and negative impact of war participation, to preserve the unity and independence of the country. Neutrality has become one of the key factors for maintaining the stability and inner unity of the Confederation. Despite being forced to make some concessions and compromises in its foreign policy due to the unfavourable outside conditions during WWI and WWII, Switzerland retained its neutral status, managed to escape external military aggression, provided refuge for tens of thousands of foreigners and took an active role as an international mediator between the warring countries.

After WWII, Switzerland actively participated in supporting Europe’s post-war economic recovery and, thanks to its active neutrality, contributed to a more endurable peace and security in the world, to the process of détente, to the ease of the military and political division and the stand-off between the totalitarian and democratic states. The evolution of Switzerland’s foreign policy continued ← 13 | 14 → after the changes that swept through Eastern Europe at the end of the 80s and early 90s of the past century. The neutrality of the country reached new dimensions. Corner stone events include Switzerland’s accession to the UN in 2002, the broadening of the country’s cooperation with the EU, Swiss participation in international peacekeeping missions in different countries and regions across the globe, active combat against poverty in the suffering countries and promoting the democracy, the rule of law, human rights and solutions to the global issues of mankind.

Nowadays Switzerland is one of the 14 countries in Europe that have declared in a different form and degree allegiance to the policy of neutrality. Of these countries, more attention has been given to the neutrality of Sweden, Austria, Finland, Ireland and others. Compared to them, Switzerland has been a neutral state for the longest time. What sets it further apart is the fact that the other countries’ neutrality is manifested mainly or exclusively in its military dimension. In Austria, Sweden and Finland it is replaced by the term “non-alignment” and in Ireland by “military neutrality” which in both cases is tantamount to non-participation in military alliances.

Switzerland is the only country from those mentioned above that is not a member of the EU and therefore is not obliged to comply with the EU common foreign and security policy. At the same time, it is the only one among them that is a member of EFTA which does not promote cooperation in the field of military policy. Switzerland has adopted the standpoint that – with the exception of the UN – neutrality rules out any engagement in international organizations made up of supranational decision-making bodies. That’s why the country only participates in international economic sanctions pursuant to resolutions adopted by the UN Security Council and decisions endorsed by the EU or backed by the international community. To this day, Switzerland is still seen as a country which to the greatest extent embodies the idea of neutrality in foreign policy and military affairs.

This book follows the historical evolution of Switzerland’s emergence as an independent state, its system of governance and neutrality policy. It analyses the long and hard road the country has followed to reach its modern identity as a highly developed country whose political system is rooted in the democratic values. The principles on which the country has been founded are given special focus, together with the way in which Switzerland’s modern system of federal governance functions, the role of the legislative power (the Federal Assembly), the government (the Federal Council), the interrelation between representative and direct democracy, the role of popular initiatives and federal referendums in domestic and foreign policy decision making. Switzerland’s place in Europe and ← 14 | 15 → in the world is shown through authoritative expert country rankings based on major indicators in the sphere of democracy, economic and social development.

The analysis of Switzerland’s neutrality is given special attention in this book – its emergence, the principles on which it has been founded, how it is manifested in peace time and in periods of international conflicts, chiefly during WWI and WWII, how it has adapted to the fluctuating external environment, especially after the healing of the division of Europe toward the end of the last century, the characteristics it has in common with other neutral European countries and special features which set it apart, why is it still widely perceived as corresponding to the greatest extent to the embodiment of the idea of neutrality in foreign policy and military affairs.

The author is grateful for the valuable assistance he received in writing this book from the Swiss foundation “Konstantin and Zinovia Katzarovi”. The book is dedicated to its founder – Professor Konstantin Katzarov.

The author would like to thank Professor Bernard Voutat from the Institut d’Etudes Politiques et Internationales, Université de Lausanne, for his selfless support in writing this book. ← 15 | 16 → ← 16 | 17 →

Historical evolution of the state and political system of Switzerland

I.The Old Swiss Confederacy: Origins, territorial expansion, religious wars

Switzerland’s official status from the moment of its establishment is a confederacy, with the exception of a few years at the end of the 18th and the beginning of the 19th century when it was a republic1. In fact, Switzerland is not a confederation in the sense used in the modern legal interpretation of this type of state governance. The generally accepted definition of a confederation is that it is a union of sovereign states which retain a high degree of independence. They delegate to the central government limited powers in the sphere of defence, foreign policy, and foreign trade, they introduce a single currency, etc.

In the initial phase of its emergence as an independent country (1781–1789) the USA was also a confederation of 13 independent states. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the German Confederation was created in Europe, consisting of Austria, Prussia and some 30 smaller autonomous states and cities. After its dissolution in 1866, the North German Confederation was established in its place which included 22 countries and lasted only four years. Other examples from the more recent past are the United Arab Republic (1958–1961), formed on the basis of a union between Egypt and Syria, and the United Arab States in 1958–1961 between the United Arab Republic and North Yemen. In 2003–2006, a union of Serbia and Montenegro existed in South-East Europe, which was also a confederation. The model of governance of Canada, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other countries can be regarded as a combination of federal and to a lesser extent confederate traits.

Switzerland is a case apart. Although it has defined itself as a confederation from its very inception, the characteristics of the Swiss state corresponded to this model of state governance only in the initial period of the country’s existence. It evolved with time and began to resemble and in some regards even to behave as a federal state. In our day and age, Switzerland’s constitutional definition as a confederation is more of a reflection of historical continuity than an actually existing form of state governance.

The beginning of the establishment of the Swiss state is considered to be the Federal Charter signed in early August 1291 by three territorially separate self-governing communities in the Alp valleys – Schwyz (from whose name derives ← 17 | 18 → the name of the country), Uri and Unterwalden. They were the primitive precursors of the cantons of today which form the main elements of the Swiss confederation. Cantons also exist as administrative units in France, Luxemburg, Bosnia and Herzegovina and elsewhere, but only in Switzerland did they have and still retain a high degree of autonomy which lends them the status of small states. At the time of the signing of the Federal Charter neither they nor the newly-created confederate union had any state-defining characteristics. The confederation continued to be a part of the Holy Roman Empire. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted in Switzerland that the Federal Charter is the founding document of the Swiss state. The supposed date of its signing – 1 August, is declared Swiss National Day.

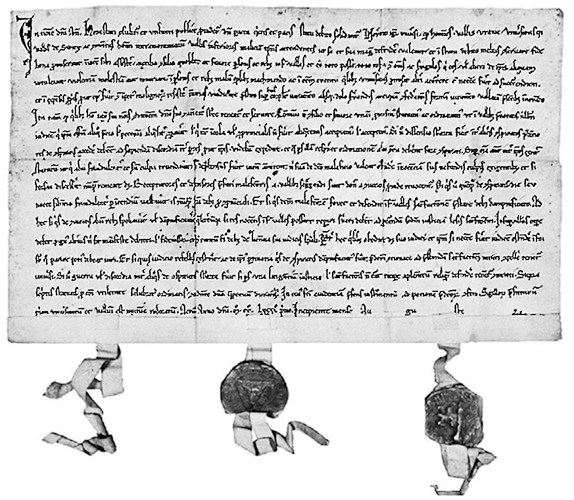

Federal charter of 1291

Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cc/Bundesbrief.jpg/680px-Bundesbrief.jpg

The signing of the Federal Charter was motivated by the desire of the residents of the three cantons to resist the Habsburg dynasty which at that time ruled the Holy Roman Empire. The desire for autonomy and the forging of a military alliance between the cantons was also fuelled by the rivalry existing in the region which became an important transport corridor after a road was built through the Saint Gotthard Massif. The Federal Charter, written in Latin, basically represented an obligation for eternal union between the three cantons, and its main object was the joint defence against any outside aggressor.2 ← 18 | 19 →

An original copy of the Federal Charter was discovered in 1724 and published some 35 years later. The fundamental significance of this document which lay the foundations of the Swiss state was only recognized toward the end of the 19th century. Besides the Federal Charter, there is also the mystical tale of the so-called oath at Rütli. This is a mountain meadow near Lake Lucerne, where according to legend in 1307 representatives from the three cantons swore to help each other if ever invaded. The oath at Rütli is considered to be the foundation of the Swiss state. A large painting showing a magnificent view of the Rütli meadow hangs in the plenary chamber of Switzerland’s Federal Assembly.

There have been other attempts at unification of the communities and cities which existed at the time on the territory of present-day Switzerland. The most important of them was the establishment of the so-called Bourguignon confederation, which represented several unions in the creation of which Bern played a crucial role. The process of unification began in the early 13th century and continued well into the second half of the next century with the admission of the cantons Fribourg, Neuchâtel, Solothurn, Vaud, Basel, Lausanne and other lesser urban and rural communities. Similar agreements were also signed with Austria.3 The alliance forged between the three cantons with the Federal Charter proved to be strong and grew into the nucleus for the future Swiss state which began to expand through the acquisition of new cantons. In the 14th century, the confederation already consisted of eight cantons. In addition to Schwyz, Uri and Unterwalden, it included Lucerne (1332), Zurich (1351), Zug, Glarus (1352) and Bern (1363). At the beginning of the 16th century, their number reached 13 cantons as the Swiss confederation was joined by Fribourg and Solothurn (1481), Basel, Schaffhausen (1501) and Appenzell (1513). The Swiss confederation grew not only through the accession of new cantons but also through conquering new territories which were given different status. There were four types of territories. The first was represented by the associated states, cantons, duchies, etc. The second type included the condominiums which were also the most numerous. Another type of territory were the protectorates. There were also non-associated regions.

During the period of its existence, the Old Swiss Confederacy led numerous wars. Its main adversary was the Holy Roman Empire, whose domination it challenged aiming at becoming an independent state. On the other hand, separately or jointly, the Swiss cantons engaged in warfare aimed at conquering new territories. At the end of 1315, in the village of Brunnen, in the canton of Schwyz, the three cantons signed a new treaty for mutual assistance, known as the Pact of Brunnen. The document reaffirmed the provisions of the Federal Charter of 1291, to which new mutual agreements were added. They also provided for broadening the non-military cooperation between the cantons.4 The ← 19 | 20 → Pact of Brunnen has long been regarded as the foundational document of the Swiss confederation well into the end of the 19th century.5

Despite the fact that new cantons and territories were added to the confederation in the 14th and the 15th century and that it scored a number of military victories against the Holy Roman Empire, it took a long time before Switzerland was internationally recognized as an independent country. The first step in this direction was the Treaty of Basel signed in 1499 after the end of the war between the cantons of the confederation and the Holy Roman Empire, known as the Swabian War. With this treaty, the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I de facto recognized the independence of the Swiss state.6 The international recognition of the confederation came significantly later – in May-October 1648, when the Peace Treaty of Westphalia was signed, putting an end to the Thirty Years’ War.

The Old Swiss Confederacy was a heterogeneous state bearing a closer resemblance to a union of independent cantons whose relations were not based on a system of rules and obligations but more often than not were settled through mutual agreements. The shape, scope and terms of the co-operations thus established varied. In fact, they represented written agreements between the rulers of the individual cantons, cities or territories. The treaties usually covered the mutual obligations for assistance in the event of outside aggression, the allocation of rights for governing condominiums, the manner of resolving disputes or settling debts, joint actions against criminals, common trade regulations, etc.

The first written agreement directly referencing the confederation dates from 1370. It was drawn up after the canton of Zurich was prevented from punishing a senior priest who having committed an offence had turned for help to Austria. This led the Swiss cantons, with the exception of Bern, to sign the so-called Priests’ Charter (Charte des prêtres, Pfaffenbrief) which contained provisions which contributed to the strengthening of the unity in the confederation. Under this Charter all cantons agreed to maintain safety on the roads between Zurich and the St. Gotthard Pass, to follow common procedures for resolving disputes in settling debts, for dealing with criminals, etc.

All inhabitants, including those in the employment of Austria’s rulers, had to swear fealty to the cantons in which they lived. The powers of the authorities in each canton were increased, in particular in the sphere of law and military affairs. This Charter is widely regarded as marking the beginning of the transition from personal agreements between individual rulers to signing treaties with legal power within the confederation. For the first time, the Charter of 1370 refers to the inhabitants of the cantons as “confederated” (confédérés). If a resident of a canton who had renounced his right to be a confederated resident harmed in any way an ← 20 | 21 → other confederated resident, he was not allowed to return to live in the same town or canton before paying the latter damages.7

Details

- Pages

- 407

- Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653041613

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653988086

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653988079

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631650608

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-04161-3

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (May)

- Keywords

- State Governance Staatsführung Neutralität Direkte Demokratie Referendums Neutrality Schweiz

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 407 pp., 10 b/w fig.