Language Proficiency Testing for Chinese as a Foreign Language

An Argument-Based Approach for Validating the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK)

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 1.1 An integrative validation of the old HSK

- 1.2 Why a validation of the old HSK is useful

- 1.3 Research overview and approach

- 1.4 History of the HSK

- 1.5 Other Chinese language proficiency tests

- 1.6 Transcription system in this work

- 2 Language proficiency

- 2.1 Definition of central terms

- 2.2 Ability/trait vs. context/situation/task

- 2.3 Language proficiency in CFL

- 2.4 Current views of language proficiency

- 2.5 Approach for this work

- 3 Test theory for language testing

- 3.1 Classical test theory and item response theory

- 3.2 Quality standards of language tests

- 3.2.1 Objectivity

- 3.2.2 Reliability

- 3.2.3 Validity (overview)

- 3.2.4 Fairness

- 3.2.5 Norming

- 3.2.6 Authenticity

- 3.3 Validity theory and validation

- 3.3.1 What is validity?

- 3.3.2 Criterion validity

- 3.3.3 Content validity

- 3.3.4 Construct validity

- 3.3.5 Messick’s unitary concept

- 3.4 Validation of tests

- 3.4.1 Kane’s argument-based approach to validity

- 3.4.2 Why use an argument-based approach?

- 3.4.3 An argument-based approach for the old HSK

- 4 An argument-based validation of the HSK

- Classification of the HSK

- 4.1 Trait labeling, target domain description, and target domain sampling

- 4.1.1 The intended goals of the HSK

- 4.1.2 The target language domain of the four skills

- 4.1.3 Interfaces between TCFL and testing

- 4.1.4 Content and target domain sampling

- Sampling of the target domain

- Parenthesis—The Graded Syllabus for Chinese Words and Characters

- 4.1.5 The role of the item writer and the item pool

- 4.1.6 Summary

- 4.2 Scoring/Evaluation (Inference 1)

- 4.2.1 Appropriate scoring rubrics

- 4.2.2 Psychometric quality of norm-referenced scores

- 4.2.3 Task administration conditions

- 4.2.4 Summary

- 4.3 Generalization (Inference 2)

- 4.3.1 Reliability of the HSK

- 4.3.2 Norm-reference group

- 4.3.3 Equating

- 4.3.4 Generalizability studies

- 4.3.5 Scaling

- 4.3.6 Summary

- 4.4 Extrapolation (Inference 3)

- 4.4.1 Trace-back studies—HSK’s predictive validity

- 4.4.2 Concurrent validity of the HSK

- 4.4.3 Summary

- 4.5 Explanation (Additional Inference)

- 4.5.1 HSK scores, instructional time and proficiency differences

- 4.5.2 The old HSK as a measure for productive skills

- 4.5.3 Internal construct validity

- 4.5.4 DIF studies

- 4.5.5 Summary

- 4.6 Decision-making/Utilization (Inference 4)

- 4.6.1 Standard setting

- 4.6.2 The interpretation of HSK scores

- 4.6.3 Influence on teaching and learning CFL

- 4.6.4 Summary

- 5 German HSK test taker scores and their Chinese study background

- 5.1 The HSK as a research tool

- 5.1.1 Research on proficiency and study time

- 5.1.2 Central research question

- 5.1.3 Hypotheses

- 5.1.4 Quantitative approach and goals

- 5.1.5 Population and sampling

- 5.1.6 Operationalization and investigation method

- 5.1.7 Pretesting

- 5.1.8 Survey and data collection

- 5.2 Statistical analysis

- 5.2.1 Native vs. non-native Chinese test takers

- Gender

- Status

- Age

- 5.2.2 Preconditions for investigating correlations

- 5.2.3 Relation of HSK scores to study hours and years

- Study length (SL) vs. HSK score

- Study hours (SH) vs. HSK score

- Subgroups

- Correlations between subtests and study hours

- 5.2.4 Can study hours and/or years predict Chinese competence?

- 5.3 Summary

- Hypotheses

- 5.4 Implications for CFL in Germany and Western learners

- 6 The validity argument for the old HSK

- The HSK’s purpose and target language domain

- Scoring

- Generalization

- Extrapolation

- Explanation

- Decision-making

- Overall appraisal

- Future and politics

- 7 Conclusion

- Tables

- Figures

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Bibliography

| 11 →

Since the Reform and Opening policy of the People’s Republic of China in 1978, the economic and political importance of China has grown enormously, and more and more individuals want or need to learn Chinese. Although reliable data about the worldwide number of all learners of Chinese do not exist (Sūn Déjīn, 2009, p. 19), there is evidence of a strong increase. In South Korea, there are around 100,000 learners in schools and universities, and together with those who study via TV, radio or other media, they exceed 1,000,000 (Niè Hóngyīng, 2007, p. 87). In Japan, Chinese has become the second most popular foreign language behind English with 2,000,000 learners (Sū Jìng, 2009, p. 88). Europe still lags behind; however, in Germany more than 4,000 students learn Chinese in intensive language programs at universities and colleges (Bermann and Guder, 2010), while an unknown number studies in optional classes. Together with learners at secondary schools, all students of Chinese in Germany number 10,000, leaving only France with more Chinese learners in Europe (Fachverband Chinesisch, 2011). In the United States, nearly 2,000 high schools already offer Chinese, which has become the third most popular language behind English and Spanish (ibid.).

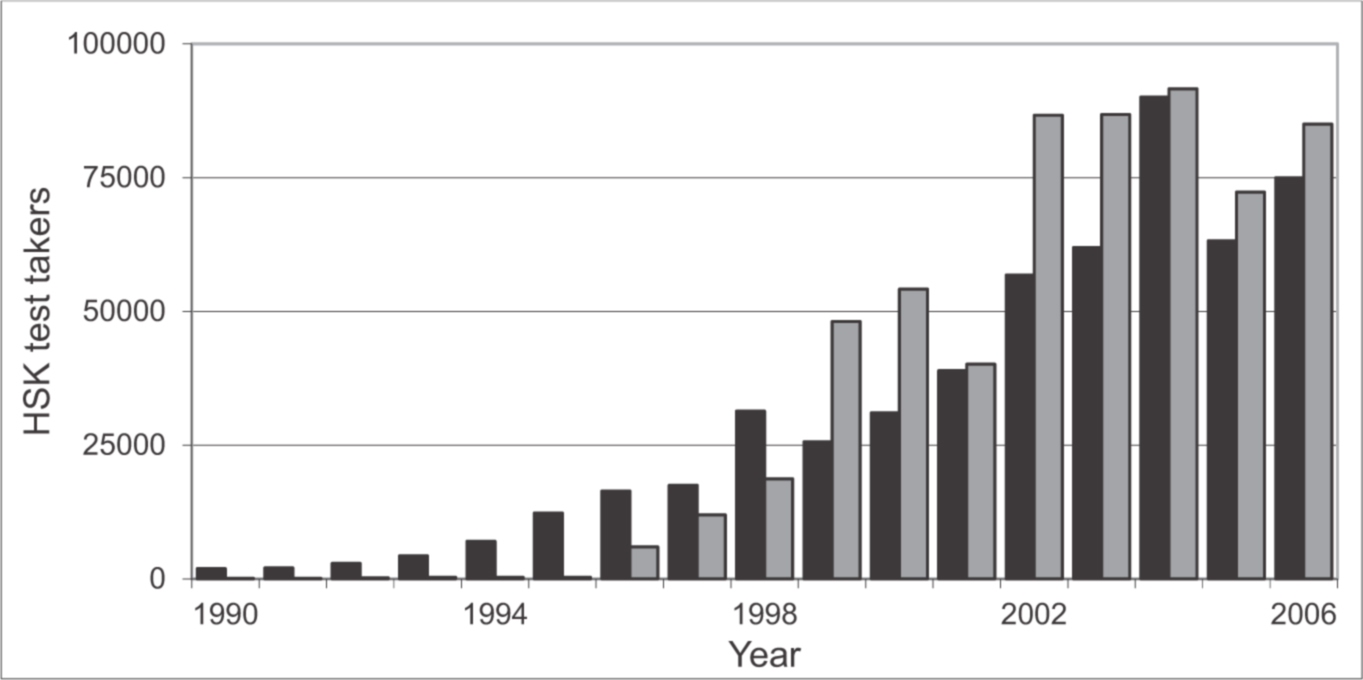

Figure 1: HSK test taker development (black: foreign group; gray: Chinese ethnic minorities).

For 2006, bars estimated on a total number of 160,000 (Yáng Chéngqīng and Zhāng Jìnjūn, 2007, p. 108); other data from Sūn Déjīn (2009, p. 20). Data rights shifted from the HSK Center to the Hanban5 in 2005. ← 11 | 12 →

In addition, more and more students participate in language proficiency tests for Chinese as a foreign language (CFL) (cf. Figure 1), and the number of tests has also risen. Since the beginning of the 1980s by far more than twenty tests have been launched (cf. chapter 1.5). These tests fulfill different purposes, such as helping test takers enter a Chinese or Taiwanese university, placing students into appropriate language courses, giving credit points to students who have gained considerable knowledge prior to their studies, or helping companies to find employees who are able to do business communication and translation work. In South Korea, many job applicants are expected to be able to use Chinese due to the strong economic ties between China and Korea, and the level of proficiency is often directly related to salaries (Niè Hóngyīng, 2007, p. 87);there, the HSK (Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì 汉语水平考试), the official Chinese proficiency test from the People’s Republic of China (PRC), has partially a major impact on test takers’ lives or affects “the candidates’ future lives substantially,” and the test can be considered as a high-stakes test (Davies, Brown, Elder, Hill, Lumley, and McNamara, 1999, p. 185; Bachman and Palmer, 1996, pp. 96–97).

The HSK has the largest test population of all CFL tests, and it has prompted the most research. In 2007, more than 1,000,000 test takers participated in it (Wáng Jímín, 2007, p. 126). In Germany, the HSK was the only CFL proficiency test which test takers could take until 2009, when the Taiwanese TOCFL (Test of Chinese as a Foreign Language Huáyǔwén Nénglì Cèyàn 華語文能力測驗) entered Germany. In 2010, the “new HSK” replaced the former HSK version.6 However, in China (2013) some universities still offer the old HSK.

In fact, overhauling the old HSK was necessary because it had several major limitations: the HSK resembled the format of a discrete-point test7; it did not directly assess oral and written productive skills; in addition, the score and level system was not easy to comprehend (cf. Meyer, 2009), which made it difficult for stakeholders to interpret the meaning of HSK scores. On the other hand, the HSK had several advantages: it was a highly standardized multiple-choice test with very high objectivity and reliability. Both latter qualities derived partly from the fact that the test almost exclusively used items in multiple-choice format. The test intended to measure the Chinese language ability needed for successfully studying in China, and test takers’ results were set in relation to a norm-reference group. It was a high-stakes test for many Koreans, Japanese, Chinese ethnic minorities, and in part, other foreigners interested in studying in China. The (old) HSK has now been used for ← 12 | 13 → more than 20 years, during which time it underwent changes, and research is still partly being conducted. However, the major question is which inferences can be drawn from test scores of test takers, especially those with a “Western” native language background, such as individuals from Germany. Therefore, this work will examine the quality of the (old) HSK, with the core question being whether scores or the interpretation of HSK test scores can be considered valid? Is it a fair exam, or is it biased8 in favor of Japanese, Korean or other East Asian test takers9? What do HSK scores tell us about learners of Chinese?

1.1 An integrative validation of the old HSK

Although many HSK validation studies have already been conducted, this is the first work providing an integrative validation approach, which attempts to incorporate all studies. But before starting this undertaking, one should stress one important fact: there is no perfect test. As Cronbach ([1949] 1970) has stated:

Different tests have different virtues; no one test in any field is “the best” for all purposes. No test maker can put into his test all desirable qualities. A design feature that improves the test in one respect generally sacrifices some other desirable quality. Some tests work with children but not with adults; some give precise measures but require much time; … Tests must be selected for the purpose and situation for which they are to be used. (ibid., p. 115; italics added)

Thus, this work examines whether the HSK is a valid test for a specific purpose.10 For what kind of use do the interpretations of HSK scores make sense? How can we interpret HSK scores and what inferences can we draw from HSK results? What is the intended use of the HSK, and what else should the HSK measure? In what sense are interpretations limited? What do the HSK and Chinese language testing research tell us about the quality of the HSK? What are the logical inferences leading from HSK test performance to conclusions about test takers? Which parts of the HSK consist of weak inferences that should be improved? And finally, what are the intended and unintended outcomes of using the HSK?

Another question concerns whether the HSK can be used as a diagnostic tool for the Chinese language acquisition process, especially for Western learners. ← 13 | 14 → Many Western learners did not consider (old) HSK “scores”11 a valid measure of their Chinese language competence, and they complained the HSK had several shortcomings. First, the HSK did not assess productive oral skills. Second, Chinese characters were displayed in all sections and subtests (e.g., also in the multiple-choice answers of the listening subtest). And third, the HSK was mostly a multiple-choice test showing features of a discrete-point test, which did not replicate authentic language tasks.12 In contrast, HSK researchers claimed that the HSK “conforms to objective and real situations” (Liú Yīnglín, [1990] 1994, p. 1, preface).

This work shows that the old HSK provided valid score interpretations to assess Chinese learners’ listening and reading abilities for the purpose of studying in China. Thus, one should consider the HSK’s specific purpose to evaluate its usefulness. The validation, or the evaluation of its usefulness, will be undertaken in chapter 4 based on HSK research. This validation study reveals weak aspects of the inferences drawn from scores of HSK test takers. For instance, inferences about test takers’ productive skills are rather limited. Hence, one major goal of this study is to clearly explain which parts of the HSK should be strengthened to provide a better estimate whether learners’ Chinese language abilities sufficed to study at a Chinese university. The validation approach used in this dissertation is an argument-based approach (Kane, 1990, 1992, 2006), which has been successfully used in recent years and has been adopted to develop the new Test of English as a Foreign LanguageTM (TOEFL®), the TOEFL iBT (Chapelle, Enright, and Jamieson, 2008).

In chapter 5, the HSK is used as a diagnostic tool estimating the learning progress of learners of Chinese in relation to the length of time they have spent studying the language in class. The study was conducted in Germany, which has one of the largest Chinese learning communities in Europe. Over two years, 257 test takers participated in this study13, and 99 learners (without any Chinese language background) provided a good estimate of how many hours an “average” German learner needed to spend in class for achieving a specific (old) HSK level. The main questions guiding this research are:

- Does a positive correlation exist between the time learners spent in Chinese language classes and HSK scores?14 ← 14 | 15 →

- If there is a relation between the time spent in classes and HSK results, what is the nature of this relation? Is it possible to estimate a regression line for predicting how long it takes to reach a certain level of proficiency in Chinese?

- What do these results tell us about the nature of the Chinese language acquisition process of German learners? What are the main factors influencing this process?

1.2 Why a validation of the old HSK is useful

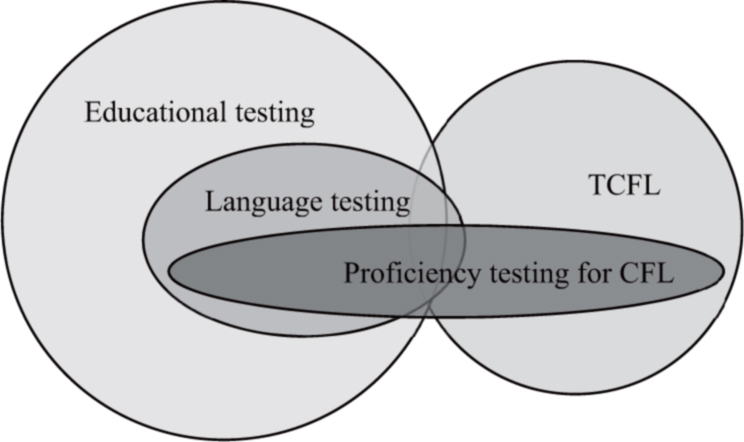

This work (a) investigates language proficiency testing for CFL, (b) will give new insight into how Western test takers acquire Chinese, and (c) discuss these issues on the basis of theoretical approaches and methods from the field of testing (especially psychological testing). Thus, perspectives from different research fields and disciplines need to be incorporated which all overlap to a certain extent (cf. Figure 2). Chinese proficiency testing influences teaching Chinese as a foreign language (TCFL). Almost all large-scale CFL proficiency tests are based on word and grammar syllabi, which, in turn, have a huge influence on course books and other learning material. At the same time, CFL proficiency testing is strongly affected by the field of language testing, which is mostly dominated by Anglo-Saxon countries, particularly the United States and England. And finally, language testing is largely embedded in the theoretical grounds provided by psychological testing.

Figure 2: Localization of research fields relevant for this dissertation.

So, why does this dissertation investigate the old HSK which was replaced by the new HSK in 2010? First, the old HSK was the most widespread proficiency test for CFL in the world, and this dissertation deals with how German test takers perform on CFL proficiency tests,15 and by 2007, it was the only proficiency test available in Germany, and empirical research could be conducted on only this test. ← 15 | 16 → Second, the HSK has one of the longest histories of CFL proficiency tests. Researchers have generated a vast number of studies, which helped to develop and to improve the HSK, and this offers a rich pool for understanding how CFL testing and research in China has developed and functions. Investigations on the (old) HSK continued until recently (e.g., Huáng Chūnxiá, 2011a, 2011b).16 Therefore, by using the concrete tool “HSK” and its research history, this work highlights the crucial mechanisms generally inherent in CFL testing. To reach this goal, the fundamental debate about today’s test theory, the concept of validity, and a useful and feasible approach for validation have been integrated into this work. Hopefully, this will offer new aspects into CFL acquisition, and a better understanding of the “CFL construct” and its assessment. As Liú Yīnglín (1994d) clearly stated, testing in CFL—like in other disciplines as well—is an ongoing process of making compromises and finding an appropriate and useful trade-off. To understand these compromises, a concrete test must be integrated into a clear and integral argumentative framework explaining what the test intends to measure.

1.3 Research overview and approach

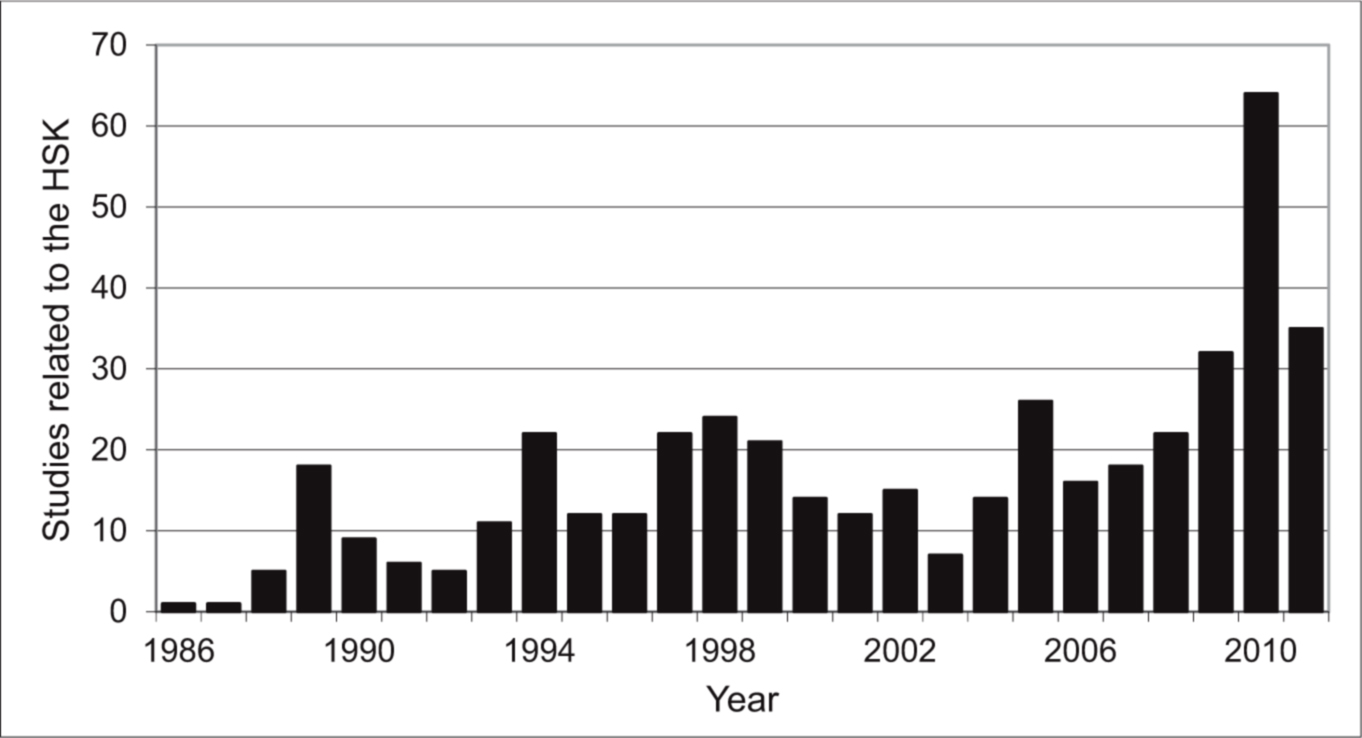

With the rise of the HSK in the PRC (1990)17 and the TOCFL18 in the Republic of China (2004), proficiency testing for CFL came to the agenda.19 More than 450 studies related to the HSK have been published, starting with Liú Xún, Huáng Zhèngchéng, Fāng Lì, Sūn Jīnlín, and Guō Shùjūn (1986).20 Many studies were published between 1989 and 2010 in the eight edited volumes on the HSK21, one edited volume deals with language test theory and CFL testing (Zhāng Kǎi, 2006a). The majority of these studies were conducted by professional HSK test developers22 for further improving the test. In the late 1990s, more critical studies followed, ← 16 | 17 → often published by test practitioners, such as test administrators or language teachers, the latter group engaged in this because their teaching got affected by the HSK. These studies were often related to washback issues. Figure 3 shows the number of HSK studies published each year.

Figure 3: Chinese studies related to the HSK or using it as a research tool (in total 421).

The Chinese literature on CFL testing has not received much attention outside of China although the number of standardized Chinese language proficiency test takers and test centers outside of China has constantly risen (Meyer, 2009). Mainland Chinese research can be divided into studies focusing on the old HSK, the Gǎijìnbǎn HSK (Revised HSK), and the new HSK. The old HSK related research can be subdivided into research on the three different HSK test formats, which covered different levels of Chinese proficiency: (a) the Elementary-Intermediate HSK, (b) the Advanced HSK, and (c) the Basic HSK. This dissertation primarily targets the Elementary-Intermediate HSK, which was the first test launched officially in 1990. This test (and its successor the new HSK) still has the highest total test-taking population of all CFL proficiency tests by far (cf. Figure 1), which is why the majority of all HSK studies examine this test. Because this dissertation focuses on the Elementary-Intermediate HSK, which is also the most important test for German test takers, it will only mention studies on the Basic and the Advanced HSK when necessary.23 HSK research was also conducted on different test-taker groups, especially on ethnic minorities, and on test takers from specific countries, ← 17 | 18 → mostly Asian countries because Asian test takers account for more than 95% of all foreign HSK test takers (Huáng Chūnxiá, 2011b, p. 61).24 Some studies investigated non-Asian test-taker groups, for example the situation in Italy (Xú Yùmǐn and Bulfoni, 2007; Sūn Yúnhè, 2011) or Australia (Wáng Zǔléi, 2009). Unfortunately, none of these studies explicitly differentiates between test takers who have a native Chinese language background and those who do not; exceptions are Yè Tíngtíng’s (2011) study on the situation in Malaysia and Shàn Méi (2006) who investigated the HSK’s face validity. This dissertation will initially provide data distinguishing between both groups, and it will give new insights to learners who have absolutely no native Chinese language background.25 HSK research covers a vast variety of topics, even the historical aspects of testing in China.26 Other HSK research deals with the first revised version of the HSK, the Gǎijìnbǎn 改进版 HSK (Revised HSK, launched in 2007) and the new HSK (新版 HSK Xīnbǎn HSK, launched in 2010). The volume edited by Zhāng Wàngxī and Wáng Jímín (2010) solely deals with the Gǎijìnbǎn HSK. Most studies on the new HSK have occurred in recent years, starting with Lù Shìyì and Yú Jiāyuán (2003) who published the first essay about the new HSK.27 Up to now, around 40 studies in total concern the Gǎijìnbǎn HSK and the new HSK. Both in China and in Taiwan, one monograph on CFL testing has been published.28 Wáng Jímín (2011) covers the whole spectrum of language assessment, with many examples coming from CFL testing, while Zhāng Lìpíng (2002) focuses completely on testing for CFL.

Compared to the situation in China, Western research is rather scanty. Several studies originated in the United States, most of which deal with classroom assessment (e.g., Bai, 1998; Muller, 1972) or test formats or test types (Ching, 1972; ← 18 | 19 → Lowe, 1982; Yao, 1995). Chun and Worthy (1985) discuss the ACTFL29 Chinese language speaking proficiency levels. Hayden (1998) and Tseng (2006) examine language gain. In Germany, only five studies on the HSK have been published (Meyer, 2006, 2009; Reick, 2010;Ziermann, 1995b, 1996). Fung-Becker (1995) writes about achievement testing for CFL, and Lutz (1995) presents some thoughts on methods for assessing the oral ability of learners of Chinese.30

On the one hand we can find considerable knowledge about CFL testing in China; on the other hand, outside of China nearly no literature exists. Thus, this work presents the major findings of the rich HSK research to a Western audience, and it will identify crucial questions in CFL proficiency testing and explain why a “perfect” language proficiency test for CFL will never exist because testing goals, test takers, and the context in which the Chinese language is used and assessed, as well as the resources and the testing technologies used will always vary and have to be specified and adjusted to the specific needs and uses of a test. However, the crucial points or main theoretical issues will remain. I hope this study can contribute to the above-mentioned fields by clearly revealing what these main issues are and how they affect CFL testing.

Over time, the quality of HSK studies has gradually improved. Studies in the 1980s were concerned with the foundation of the HSK, which especially included the target language domain, the scoring, and the reliability of the HSK. One of the main targets of researchers at that time was to provide norm-referenced scores and to make the HSK a stable measure. Validation studies began in 1986 and emerged in greater numbers in the 1990s. In the 2000s, washback studies emerged. Jìng Chéng (2004) claims that researchers who were not involved in the HSK test development process had no access to test taker data samples and could not generate results large enough to have statistical value, and the author argues that non-test developers had to engage in more qualitative research than quantitative (p. 23). However, HSK research maintained high quality and shifted from larger fields to increasingly specialized topics. Though confirmatory studies initially dominated HSK research, several studies were very critical and disclosed controversial points. Non-test developers later expanded on these critiques. One specific criticism stemmed from teachers and universities in the autonomous region Xīnjiāng, whose participants had outnumbered the foreign test takers after 1999 (cf. Figure 1, p. 11), and for whom the HSK became a high-stakes test because admission officers required HSK certificates as part of the decision-making process to admit ethnic minority students to Chinese universities and colleges. ← 19 | 20 →

Thus, some investigations on the HSK that are thematically related to this work provided rich information for this dissertation and were quoted in several chapters31, while some could be summarized in one or two sentences, and others were not mentioned because they did not provide new insights. The majority of HSK studies used quantitative approaches; qualitative studies investigating single learners only occasionally occur, though the idea of combining different methods in a useful way appropriate for the specific research field—triangulation (e.g., Grotjahn, [2003] 2007, p. 497;Kelle, [2007] 2008)—is known among Chinese language testing experts (e.g., Chén Hóng, [1997c] 2006, p. 235).

The HSK research was used to validate the test (chapter 4), and the validation focuses on the Elementary-Intermediate HSK. In chapter 2, the term language proficiency will be discussed in detail, to foster a better understanding of Chinese HSK research. In addition, terminology relevant for this dissertation will be defined. Chapter 3 provides the theoretical foundation of testing, presenting the quality criteria in language testing, and it explains the crucial term of validity, how this term has been understood in psychological testing, and how it is used in this dissertation. Based on this validity concept, the theoretical approach underlying the validation in this work will be depicted in detail. Chapter 5 is an extension of the HSK validation with an empirical investigation on HSK test takers in Germany. The validity argument for the HSK will be presented in chapter 6. Afterwards, the conclusion follows in chapter 7.

Sūn Déjīn (2009) divides the development of the HSK into three periods: (a) an initial phase (chūchuàngqī初创期) from 1980 to 1990, (b) an expanding stage (tuòzhǎnqī拓展起) from 1990 to 2000, and (c) an innovative stage (chuàngxīnqī创新期) from 2000. A fourth stage started with the new HSK in 2010 and ended the innovative stage.

In 1981, the development of the HSK started with research on small-scale tests. By that time, the HSK was strongly affected by standardized language tests in the United States and England, especially the TOEFL, which had just reached the Chinese mainland and shifted the focus in Chinese foreign language didactics from language knowledge to language ability (p. 19; cf. Liú Yīnglín, [1988b] 1989, p. 110–111; Sūn Déjīn, 2009). After founding the “HSK design group” (Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì Shèjì Xiǎozǔ 汉语水平考试设计小组) in December 1984, led by Liú Xún 刘珣 and consisting of ten members32, the first test was developed and ← 20 | 21 →pretested in June 1985 at the BLCU33 (Liú Xún et al., [1986] 1997, p. 77; Liú Yīnglín, [1990b] 1994, p. 45; Liú Yīnglín, et al., [1988] 2006, p. 23; Sūn Déjīn, 2007, p. 130; Zhāng Kǎi, 2006c, p. 1). Liú Xún reported the results of the 1985 pretest at the first conference on “International Chinese Didactics,” where they caused a “stir.” Afterwards, further large-scale pretests were conducted in 1986 and 1987; in 1988, the BLCU launched the first official HSK and issued certificates to the test takers, who have to pay a test fee since 1989 (Sūn Déjīn, 2007, p. 130, 2009, p. 19). By that time, the HSK consisted merely of the test format that was later renamed Elementary-Intermediate HSK.

From June 1985 to January 1990, 8,392 test takers from 85 countries participated in the HSK, and the examinations were held at 33 test sites in 16 Chinese provinces, cities, and autonomous regions (Liú Yīnglín and Guō Shùjūn, [1991] 1994, p. 12). From 1985, five large-scale pretests were administered once a year. In March 1989, BLCU established the Chinese Proficiency Test Center (HSK Center; Hànyǔ Shuǐpíng Kǎoshì Zhōngxīn 汉语水平考试中心; Zhāng Kǎi, 2006c, p. 2);the Center provided the professional basis for HSK development and research. In 1990, the HSK was appraised by experts and officially launched.

In 1991, the HSK was launched outside of China, and the number of test takers steadily increased.34 Because the HSK only assessed the elementary and intermediate proficiency levels, the “Advanced HSK” (Gāoděng 高等 HSK) was introduced in 1993, and the original HSK was renamed to Elementary-Intermediate HSK (Chū-zhōngděng 初、中等 HSK). In 1997, the Basic HSK (Jīchǔ 基础 HSK) entered the scene.

Details

- Pages

- 349

- Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653039344

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653990560

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653990553

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631648919

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-03934-4

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (March)

- Keywords

- Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi (HSK) Sprachtest Language proficiency Language gain Argument-based approach for validation

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 349 pp., 41 b/w fig., 129 tables