The Kaiserslautern Borderland

Reverberations of the American Leasehold Empire

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- 1. Introduction: The Kaiserslautern Borderland

- 1.1 An Unexpected Encounter

- 1.2 The Borders of the Kaiserslautern Area

- 1.3 Design & Method

- 1.4 State of Research

- 1.5 Content Map

- 2. The Kaiserslautern Area in Terms of Borders

- 2.1 Three Spheres: Approaching the Spatial Concept of the Kaiserslautern Borderland

- 2.1.1 The Border Line as a Spatial Concept

- 2.1.2 Mapping the Border

- 2.1.2.1 Approaching the Border

- 2.1.2.2 The Threshold – Crossing the Border

- 2.1.2.3 Beyond the Fence

- 2.1.3 The Un-Territorial Border

- 2.2 The Border as a Regional Phenomenon

- 2.2.1 Region as a Concept: the German Sphere

- 2.2.2 The American Side

- 2.3 The Borderland

- 2.3.1 Concept and Specific Characteristics

- 2.3.2 Borderland Demographics

- 2.4 Locating the Geographical Borderland

- 3. The Legal Borderland

- 3.1 The Basic Legal Notion

- 3.2 The Contractual Framework

- 3.3 The Special Legal Status of the American Military in Germany

- 3.4 The Legal Landscape

- 3.4.1 Jurisdiction

- 3.4.2 Policing

- 3.4.3 The Use of Space

- 3.4.4 Public Policy, Taxation, and Customs Regulations

- 3.5 Mapping Legal Space

- 4. Borderland Governance

- 4.1 Regional Politics in Terms of Borders

- 4.2 The American Political Sphere

- 4.2.1 Systemic Differences

- 4.2.2 The KMC as a Kind of Municipality

- 4.2.3 The Structures of the Military Administration on the Local and Regional Levels

- 4.2.3.1 Internal Structures as a Quasi-Communal Administration

- 4.2.3.2 Administrative Structures of the U.S. Forces Above the Regional Level

- 4.2.4 The Overall Structural Character of the American Military Administration

- 4.3 The German Political Sphere

- 4.3.1 Structural Foundation

- 4.3.2 The International Exposure of the German Administrative System in Rhineland-Palatinate

- 4.4 German-American Borderland Politics

- 4.4.1 Systemic Aspects

- 4.4.1.1 The Kaiserslautern Area as Binational Contact Sphere

- 4.4.1.2 The International Diplomacy of Rhineland-Palatinate

- 4.4.1.3 Lessons Learned in Rhineland-Palatinate: The Need for Cross-Border Political Activities

- 4.4.1.4 Local Level Cross-Border Diplomacy

- 4.4.1.5 Absence of Contact

- 4.4.1.6 The KMC as Quasi-Domestic Destination

- 4.4.2 Contexts and Topics of Borderland Politics

- 4.4.2.1 Cross-Border Location Policy

- 4.4.2.2 The Rhein-Main Transition Program

- 4.4.2.2.1 State and Federal Involvement

- 4.4.2.2.2 Local Involvement

- 4.4.2.3 Noise Pollution as an Issue of Local Borderland Politics

- 4.4.2.4 The Cross-Border Dispute Over Ramstein’s New Aquatic Center

- 4.4.2.5 A Joint German-American Water Supply System

- 4.5 Coming to Terms With Borderland Politics in the Kaiserslautern Area

- 5. The Regional Economy in Terms of Borders

- 5.1 The Regional German Economy

- 5.2 The U.S.-(Military) Economy in the Kaiserslautern Area

- 5.2.1 A Quasi-American Economy – AAFES and DECA

- 5.2.2 KMCC – Ramstein’s New Shopping Mall

- 5.2.3 The American Consumer Island

- 5.3 The Economic Borderland – Borderland Economy

- 5.3.1 The U.S. Forces as Regional Employer for Germans

- 5.3.1.1 Legal Aspects and the Borderland Constellation

- 5.3.1.2 Intercultural Aspects and the Borderland Constellation

- 5.3.2 The Regional German-American Housing Market

- 5.3.3 German Economic Activity Within the American System

- 5.3.4 The General Off-Base Borderland Sector

- 5.3.4.1 The American Parallel Market

- 5.3.4.2 Key Segments of the General Borderland Sector

- 5.3.4.2.1 The Mobility Market

- 5.3.4.2.2 The Life Embellishment Market

- 5.3.4.2.3 The Hospitality Market

- 5.3.4.3 The Fringe of the Economic Borderland

- 5.3.4.4 Borderland Contraband

- 5.4 The Creative Force of Difference

- 6. Society and Culture in the Borderland

- 6.1 Structural Aspects of Socio-Cultural Life

- 6.2 National Cultural Spheres

- 6.2.1 A Selective Overview of Local American Institutions and Services

- 6.2.1.1 The American School System

- 6.2.1.2 Leisure and Family Activities

- 6.2.1.3 Special Cultural Events

- 6.2.1.4 Sports, Entertainment & Media

- 6.2.1.5 Religious Life

- 6.2.1.6 Private Initiatives and Clubs

- 6.2.2 The General Character of the American Socio-Cultural Scene

- 6.3 The Cultural Borderland

- 6.3.1 German-American Clubs and Institutions

- 6.3.1.1 German American International Women’s Club Kaiserslautern

- 6.3.1.2 German-American Friendship Club Trippstadt

- 6.3.1.3 The Atlantic Academy of Rhineland-Palatinate

- 6.3.2 General Clubs and Initiatives

- 6.3.2.1 The American German Business Club

- 6.3.2.2 The Rheinland-Pfalz International Choir

- 6.3.2.3 The Native American Association of Germany e. V.

- 6.3.2.4 The Kaiserslautern Pikes – American Football Club

- 6.3.2.5 World War II On Your Own

- 6.3.3 Churches and American-German Contacts

- 6.3.3.1 The Absence of Contacts

- 6.3.3.2 Contact

- 6.3.4 German-American Contact in the Public Cultural Scene

- 6.3.4.1 Kammgarn Kaiserslautern

- 6.3.4.2 Pfalz Theater Kaiserslautern

- 6.3.4.3 Stadthalle Landstuhl

- 6.3.5 Borderland Media

- 6.4 The Impact of the Borderland on Socio-Cultural Activity

- 7. Space and Place: The Spatial Concept of the Kaiserslautern Borderland as a Key to the Analysis of German-American Contact

- 7.1 A Spatial Dichotomy

- 7.2 The KMC Territory

- 7.2.1 A Space Without Place?

- 7.2.2 Heterotopia: The Other Place

- 7.2.3 The American On-Base Sphere: Heterotopia or Non-Place?

- 7.3 The Kaiserslautern Borderland

- 7.3.1 Influences on Borderland Interaction

- 7.3.2 The Kaiserslautern Borderland: A Rudimentary Type of Place

- 7.3.3 The Ready-Made Region

- 7.4 Coming to Terms with the Borderland Processes

- 8. Borderland Asymmetries – An Unequal Encounter

- 8.1 Space

- 8.2 Time

- 8.3 Power

- 8.3.1 Structural Power in German-American Military Relations

- 8.3.2 Interdependence in German-American Relations

- 8.3.3 Asymmetry of Power in German-American-Relations

- 8.4 The Asymmetric Borderland

- 9. Conclusions and Prospects

- 9.1 Coming to Terms With the Borderland

- 9.2 The Borderland Setup

- 9.2.1 The Border as Spatial and Functional Source of Regional Structures

- 9.2.2. The Borderland as Regional Cohesion

- 9.2.3 Asymmetries as Specific Development Parameters

- 9.3 Life in the Kaiserslautern Borderland

- 9.3.1 The Parameters of Borderland Life

- 9.3.2 Borderland Society

- 9.3.3 Borderland Identity

- 9.4. Policy Recommendations

- 10. Bibliography

List of Figures

Fig. 1:Structural representation of a basic borderland constellation (own diagram)

Fig. 9:Contexts of the legal borderland constellation in the Kaiserslautern area (own diagram)

Fig. 11:Spatial distribution of activities in the Kaiserslautern economic borderland (own diagram)

Fig. 13:Advertising in the economic borderland: targeting the dollar sphere

Fig. 14:Advertizing campaign in the Kaiserslautern borderland: welcoming the American customer

1.Introduction: The Kaiserslautern Borderland

1.1An Unexpected Encounter

Thinking of borders and their related border regions from an American context leads directly to both the U.S.-Canadian and the U.S.-Mexican border. With regard to the southern example, the terms and conditions of how the encounter between the two state systems, two economies, and two cultures takes place have been subject to extensive scholarly research during the past decades (Alvarez 1995; Martinez 1994; Herzog 1991; Romero 2008). Furthermore, also the border region between the United States and Canada has received some academic attention (Brunet-Jailly 2005; Bukowczyk 2005; Conrad 2008). The geographical possibilities for direct borderland contexts under U.S. involvement seem to be exhausted with these two cases. Nevertheless, a special regional contact between the American state system and another sovereign nation is at stake in the Kaiserslautern area, Germany. Understanding this unusual encounter in terms of a borderland represents the guiding principle of the study at hand. The perspective intends to add a new facet to the existing canon of American borderland research.

The spatial construct that leads to the presence of a self-contained American sphere within a European context has been described by Christopher T. Sandars as the American Leasehold Empire (2000). With this thought-provoking catchphrase, the author takes a systemic look at the global network of American military bases in Europe and Asia. He distinguishes this contemporary form of a power network from the traditional definition of empires, which, such as the British Empire, grounded their international presence on colonies and outposts that were mainly defined as genuine parts of the imperial territory. In comparison, the American network is based on cooperation and lease agreements without a territorial claim to the premises used. Nevertheless, the different extent of privileges connected to the contractual rights of land use may evoke conditions of quasi-sovereignty, as will be explained.

The resultant leasehold empire consists of permanent stationing contracts with NATO partners (e.g. Germany, Great Britain, Italy, and Turkey) as well as with military allies in Asia (Japan and South Korea). Since 2012, also Australia functions as a base in this power network. The focus of the study at hand is on a ← 11 | 12 → prominent and long-established component of the American leasehold empire in Germany. It is located in and around the city of Kai-serslautern.

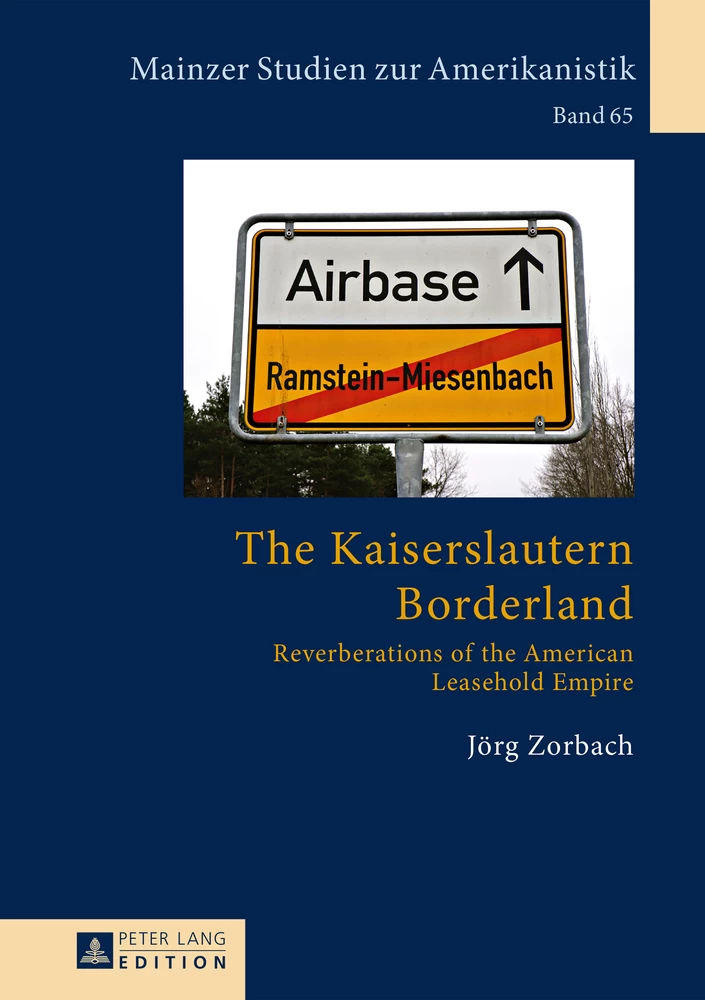

The city is situated in the southwestern German Land of Rhineland-Palatinate and has a population of today approx. 100,000 inhabitants. Kaiserslautern is the single urban center of a largely rural area characterized by village and small-town settlements, which add another 100,000 inhabitants as part of the Landkreis Kaiserslautern (Kaiserslautern County) to the region’s overall population of approx. 200,000. Even though one might rightly describe the scene as an average German provincial area, it is not unlikely that American citizens have heard about it and that the region’s military host towns like Ramstein, Landstuhl and the city of Kaiserslautern have a similar publicity as major German cities like Frankfurt or Hamburg.

Worthy of note, it is not just the regional capital of Kaiserslautern itself but also – and even more so – two small towns with approx. 7,500 and 8,600 inhabitants which have a considerable media presence in the USA: Ramstein and Landstuhl. Ramstein Air Base is the main European air transport hub for the U.S. Air Force and serves as the “gateway to Europe” (Ramstein Air Base, “KMCC” 2011) and the Middle East. Landstuhl Regional Medical Center (LRMC) functions as the U.S. forces’ main overseas treatment center for wounded soldiers. Together with a number of other towns in the area, these places represent the home of the Kaiserslautern Military Community (KMC).

The American military presence has been a part of regional life in the Kaiserslautern area for more than 60 years. During this time, this hub of German-American cohabitation has been subject to a constant process of change against the backdrop of an altering role of the United States in world politics. Having entered the area in 1945 as enemies in the terminal phase of the war against Nazi-Germany, the American troops soon found themselves more welcomed by the large majority of the local population than expected. In the initial years after the end of WWII, German-American fraternization had a tremendous momentum despite the U.S. forces’ factual role as an army of occupation.

A further paradigm shift occurred in 1951. The role of the American military changed into that of a protecting power of the demilitarized German state between the hardening fronts of East and West. The construction of major American military installations started in the area as part of the western defense strategy in the intensifying Cold War. Over the years, occupation turned gradually into alliance. The signing of the General Treaty, also called Deutschlandvertrag, between the Federal Republic of Germany and the three western allies of France, Great Britain and the USA ended the occupation period officially in 1955. Nonetheless, a power surplus of the U.S.A. in this special partnership re ← 12 | 13 → mained evident (Rödel 1995) and German sovereignty was restored entirely only after the German reunification in 1990.

After the end of the Cold War, the military presence of the U.S. forces remained a substantial element of everyday life in the Kaiserslautern area. Especially the first half of the 1990s was characterized by a significant reduction of stationed troops. With this so-called military drawdown, the population in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate had to realize its substantial economic dependence on the American military presence. The number of local German employees dropped from 24,000 in 1987 to 8,850 in 1997 (Ministerium für Wirtschaft 2010: 95).

However, the considerable reduction of troops in the years after the end of the Cold War did not herald the end of American military presence in the area as such. Germany and especially the Kaiserslautern area with its military center, Ramstein Air Base, remained an important pillar of America’s leasehold empire. Against the general trend of military consolidation, the American government even invested in the modernization of installations in the Kai-serslautern area and expanded Ramstein Air Base into the U.S. forces’ main European airlift hub. With this function, the regional American military activity took on a central – and sometimes criticized – role in America’s global war on terrorism in the aftermath of the attacks of 9/11.

Today, the American military presence in the Kaiserslautern area consists of both Army and Air Force installations scattered over several locations. Besides Ramstein Air Base and Landstuhl Hospital, the U.S. Army Garrison Kaiserslautern, Sembach Annex, the large arms depot in Bruchmühlbach-Miesau – conveniently called just Miesau Depot – and a number of further locations represent key elements of the regional network of military installations. Together, the units stationed in the area form the administrative unit of the Kaiserslautern Military Community (KMC).

The KMC is commonly referred to as “the largest American community outside of the U.S.” (Getting Around, “Kaiserslautern MC” 2009) and is currently home to approx. 49,972 American citizens (86th CPTS1 2010: 3). Remarkably, only about one quarter – or 12,855 persons – are military personnel (3). The majority of the local American2 population consists of civilian American employees and family members of both civilian and military personnel. The American School District of Kaiserslautern has approximately 6,600 American ← 13 | 14 → students in eleven schools from elementary to high school level (StateUniversity.com 2011). Consequently, despite the paramount military purpose and the still considerable nucleus of 12,855 soldiers and airmen, the Kaiserslautern military community’s civilian component represents a significant aspect of the regional American presence.

Accordingly, American life in the Kaiserslautern area must not be reduced to the military context. U.S.-American administration units, shopping and leisure facilities, an independent healthcare system, modern and gated townhouse-style housing areas, a full-fledged American school district, and a variety of further services generate an exclusive American infrastructure for the local American military community which is “comparable to a stateside community in many ways” (Getting Around, “Kaiserslautern MC”). This American enclave situation has been described as America Town (Gillem 2007) and Little America (Herget 1995; Leuerer 1997). The terms epitomize the basic mode of function of a self-contained American military and civilian system, which is largely independent from its external German context: a city behind a fence.

While the basic validity of the enclave concept of Little America can be elucidated in a great number of instances, a key proposition of the study at hand is that this perspective with its introversive conceptual focus does not suffice in order to grasp the phenomenon of the American military presence in the Kaiserslautern area in its entirety. Beyond its military purpose and despite its efforts for autarky, the American military presence also represents a varied regional phenomenon for both national groups in the area. Legal and political issues, the use of space, environmental problems, regional employment issues, economic effects, and a variety of socio-cultural aspects exemplify that Little America and its American population do get in contact with their German surroundings.

In sum, the German-American encounter in the Kaiserslautern area provides a unique regional case of direct contact and cohabitation between two otherwise transatlantic neighbors. Both German and American citizens can experience this binational situation in a variety of instances within their everyday lives. As the later description will show, the regional German-American encounter differs in a crucial aspect from other forms of temporary or rather permanent contact with a foreign national environment. Thus, neither the idea of tourism nor the concepts of immigration, ethnic neighborhoods, and enclaves are approaches which are capable of delineating the situation adequately: The Kaiserslautern area does not just provide the setting for contact between individuals of both nationalities. Rather, it witnesses also a systemic contact between the two national systems in terms of two national legal systems, administrative structures, economies and financial systems, school systems, healthcare systems, etc. Thus, binational contact on the individual level takes place under circumstances in which both sides ← 14 | 15 → are supported by the local presence of their familiar national systems. In addition to the unusual spatial constellation, also the temporal dimension – an average duration of stay of three to five years – does not correlate with conventional patterns, such as tourism or immigration.

1.2The Borders of the Kaiserslautern Area

Due to the systemic character of the German-American encounter, this study applies a perspective which does not only focus on Little America itself but also aims at understanding it within its socio-spatial context: Instead of seeing the military presence merely as an autarkic American space under military rule, the book at hand suggests to conceive of this Little America as one part of a binational border region. – An area where various aspects of two national systems interact within a joint regional context.

This novel theoretical approach to the study of American military bases abroad intends, first of all, to offer conceptual orientation. It proposes a way of seeing and consequently understanding a unique constellation on the basis of an established construct of analysis for the study of binational encounters. The Kaiserslautern case will be established as a special borderland and, thus, becomes available to comparative analysis. Literally, the borderland approach offers the possibility of coming to terms with an otherwise singular phenomenon.

As a result, the terms of border and borderland represent the guiding concepts of this study. Similarities and disparities of the Kaiserslautern constellation with the conventionally established meaning of these two concepts will add to a positioning description. Starting point for this theoretical placing is the basic notion that borders and boundaries represent most commonly “physical lines of separation between the states and countries of the international system” (Newman “Borders and Bordering” 2006: 172). While borderland scholarship has a focus on political and administrative border contexts, it also adopts a wider perspective on the study of borders:

We discovered that […] borders are not confined to the realm of inter-state divisions, nor do they have to be physical and geographical constructs. Many of the borders which order our lives are invisible to the human eye but they nevertheless impact strongly on our daily life practices. They determine the extent to which we are included, or excluded, from membership in groups, they reflect the existence of inter-group and inter-societal difference with the ‘us’ and the ‘here’ being located inside the border while the ‘other’ and the ‘there’ is everything beyond the border. (Newman “Borders and Bordering” 172) ← 15 | 16 →

Thus, in abstract terms, borders can be described as markers of difference – i.e., the point of transition from one state to another (Morehouse 1996: 20).

Consequently, the concept of the border will be the reference tool for the description of the systemic contact situation between the American military sphere and its German surroundings. Likewise, the idea of the borderland will be used in order to describe and compare the regional effects of this German-American encounter. The borderland is defined by the spatial repercussions of the border in form of cross-border interaction (Morehouse 29; Baud and Schendel 1997: 216; Martinez 1994: 5). The underlying notion of the borderland concept is that “borders create political, social, and cultural distinctions, but simultaneously imply the existence of (new) networks and systems of interaction across them” (Baud 216; parentheses in the original).

Thus, the concept of the borderland has the advantage of being able to describe contexts which exceed the conventional categories of national spatial organization. The approach does not only allow for the incorporation of inter-regional or inter-national activity, it even turns cross-border phenomena into the focus of the search for meaning. Consequently, the borderland approach facilitates the study of international contact situations due to its emphasis on the spaces in-between national categories – the margins, the thresholds.Based on such an in-depth description of what Victor Turner termed the liminal, it is not just possible to identify the specific place of transition as such but also to understand the threshold as a sphere of its own (1967: 93).

Details

- Pages

- 349

- Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653039351

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653994070

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653994063

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631646137

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-03935-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (November)

- Keywords

- Grenzstudien Grenzregion binational deutsch-amerikanische Beziehungen

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 349 pp., 17 coloured fig., 1 b/w fig.