Geoparks and Geo-Tourism in Iran

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Geoparks and Geo-Tourism Research in Iran and Neighbouring Countries (Andreas Dittmann)

- Recent Research and Scientific Studies in Geography at Shahid Beheshti Uni-versity (Mostafa Momeni)

- Caspian Tourism - Framework Conditions from an Ecological and Cultural Per-spective (Eckart Ehlers)

- Content Analysis of Iranian Tourism Websites in Development of Tourism (Mohammad Taghi Rahnemai and Farhad Jafari)

- Development and Market Trends of Tourism in Iran (Andreas Dittmann and Roozbeh Mirzaei)

- The Socio-Demographic Factors Predicting Residents’ Attitudes towards Tour-ism Impacts in Mazandaran, Northern Iran (Roozbeh Mirzaei)

- Spatial Patterns of Tourism Flows in Iran - A Comparative Study of Pre and Post Islamic Revolution Situations (Esmail Ghaderi)

- Research on Agricultural Land Use Change in Touristic Areas, Noushahr and Chalous Counties as Case Studies, Northern Iran (Mostafa Ghadami)

- Iran’s Desert Lodges and Sustainable Tourism Development (Mahmood Ziaee and Ashkan Borouj)

- The Role of Women in Geopark Sustainability - Based on Experiences of Pro-moting Ecotourism for Livelihoods through Women’s Handicraft Projects on Qeshm Island (Afsaneh Ehsani and Nima Azari)

- Promoting Nature-Based Tourism Focusing on Tourism Service Chains: A Case Study of the Uckermark Region in Germany (Neda Nouri-Fritsche)

- Demise of a Nature Reserve and a Tourist Resort, Urmia Lake (Esmail Kahrom)

- Aral Sea Syndrome and Lake Urmia Crisis - A Comparison of Causes, Effects and Strategies for Problem Solutions (Christian Opp, Julia Wagemann, Sharam Banedjschafie and Hamid Abbasi)

- Strategic Assessment of Urban Spatial Structure in Touristic Areas - A Case of Mazandaran Province, Northern Iran (Mostafa Ghadami)

- The „Kizilcahamam - Qamlidere Jeopark” - Establishing the First Geopark in Turkey (Andreas Dittmann)

- Practical Process of Strategic Planning for Development Level of Resort: The Case of Sheshtamad Resort, Northeastern Iran (Seyyed Ali Delbari and Fatemeh Khorrami)

- Attitudes of Tourism Management Students toward Tourism Jobs in Iran - Ma-zandaran University as a Case Study (Sadegh Salehi and Mokhtar Naeiji)

- The Impact of Archaeological Museums in Cultural Tourism Development: Iran’s National Archaeological Museum (Ahmad Reza Sheikhi)

- Evaluating the Quality of Accessibility to Urban Services in Medium Sized Cit-ies - A Case Study of Maragheh, Iran (Sedigheh Lofti, Ayoub Manouchehri andHassan Ahaar)

- Cultural Impacts on Indigenous Agamid Lizard Populations in South Asia: The Case of Medical Use of Gekko Gecko (Phillip Wagner and Andreas Dittmann)

- Series Index

GEOPARKS AND GEO-TOURISM RESEARCH IN IRAN AND NEIGHBOURING COUNTRIES

Andreas Dittmann

Geoparks have only recently appeared in Iran. The concept of Geoparks is highly modern and its developments need to be necessarily dynamic and therefore lay the bases for development opportunities in rural areas. Geoparks enable regions to enhance in the following ways: On the one hand, Geopark help to raise awareness about the necessity to preserve landscape and cultural characteristics, on the other hand institutional laws and regulations are established to protect the geological heritage by means of the Geopark network. Additionally, job opportunities are generated in peripheral rural areas and the Geopark can contribute to the local people’s identification with the geological and cultural heritage. As it is the Geopark’s aim to protect natural geological highlights as well as historical and cultural heritage, the idea goes beyond the idea of traditional protected areas such as National Parks that only focus on preserving the natural environment. Nonetheless the main focus lays on maintaining the Geo-Heritage for future generations. Regarding this issue, Iran has made remarkable progressions within the last years with respect to the Geoparks.

The following volume contains contributions that were gathered at the international conference on the topic “Geoparks in Iran” held in 2013 by the Institute of Geography of University of Gießen in cooperation with the Centre for Development and Environmental Studies (ZEU). The conference was financed by the German Academic Research Service (DAAD) and the University of Gießen. As it was the first conference on the topic of geo-heritage in Iran within the discipline of geography, some of the present contributions were gathered after the conference was finished.

The volume is dedicated to Prof. Dr. Mostafa Momeni (Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran, Iran) who attended the Geopark-Conference1 and wrote a contribution about the development of the subject of geography at his university but sadly passed away shortly after at a too young age. Geographers from both countries, Iran and Germany, will keep him in our grateful memories.

As Geopark activities are directly related to touristic valorization, the investigations on Geoparks are strongly related to investigation on tourism. Therefore the volume starts with a contribution by Eckard Ehlers (University of Bonn, ←9 | 10→Germany) on the historical development and actual meaning of Iranian internal tourism at the Caspian Sea. The contribution focusses on the competition for land between the necessities of touristic use and ecologically vulnerable areas. It is followed by Mohammad Taghi Rahnemai and Farhad Jafari (Tehran University, Iran), who analyze the internal tourism by means of website-analyses, proceeded by Esmail Gaderi’s investigation on the historical perspectives on scenarios on tourism of the pre- and post-Islamic Revolution (Tehran University, Iran). Roozbeh Mirzaei and Mostafa Ghadami (Mazanderan University, Iran) take us back to the Caspian Sea where the threat to the cultural and natural landscape are especially evident. Until now, little attention has been given to the potentials of Desert Tourism which is in the main focus of the contribution by Mahmood Ziaee and Ashkan Bojouj (Alamee Tabatabai University, Iran). And finally Seyed Ali Delbari and Fatemeh Korrami expose on the practical necessities and legal instruments for the implementation of Geopark-Resorts.

The contributions by Neda Nouri-Fritsche and Andreas Dittmann (University of Giessen, Germany) compare the challenges of Geoparks outside of Iran and show that the motives of the protection of Geo-Heritage and the job-creation in rural areas are common to comparable international scenarios.

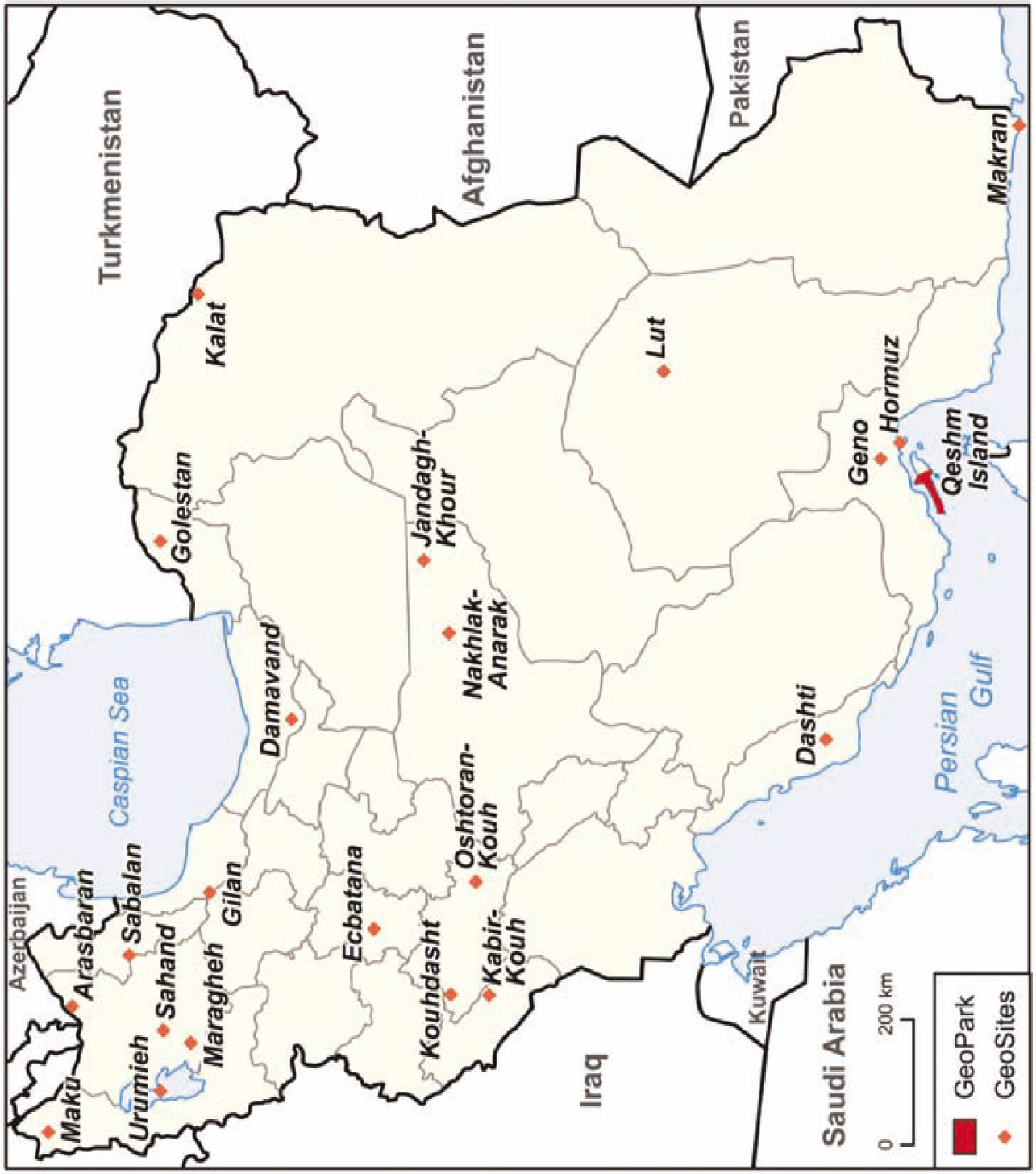

Within the realm of protected areas, the concept of Geoparks is relatively new. Since now there are few established initiatives, the characteristic challenges and constraints such as identification, designation, establishment, accrediting and reaccrediting cannot yet be investigated in-depth for Iranian cases. Nonetheless, within its region Iran is in a very advanced position regarding the establishment of Geoparks. For example the Island Queshm (Kish) in the East of the Persian Gulf in the area of the Street of Hormuz is one of the first formally established UNESCO-Geoparks in the area of Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA-Region). The other Geopark within the same region is in Morocco and is mainly a result of the initiative of Ezzoura Errami from the African Geoparks Network in the Anti-Atlas region between Tazenakht und Tamarouft (Errami, Brocx and Se- meniuk 2015). While the Moroccan Geopark is still existent and has even been extended to Southern Morocco, the initial Geopark Queshm Island has lost its UNESCO status after several requests in 2014. Reasons for this are the national and international Geopark guidelines that require the Geoparks to accomplish certain requirements to be accredited and reaccredited in order to meet the goal of sustainability. The Geopark-seal is never given indefinitely, but always for a defined period of time. In the case of the Queshm Island, as in many cases around the world, the challenge of simultaneously achieving the seemingly opposing goals of protecting geological heritage and touristic valorization of an area lead to the withdrawal of the seal. Many times economic growth is threatening what is to be protected, especially when situated in an area of economic growth, as the ←10 | 11→case in Southern Iran where a growing tourism sector is endangering what is to be protected (see chapter 11 by Afsaneh Ehsani and Nima Azari in this volume). The danger of competing use is especially serious, when the Geopark is adjacent to other areas of special use or if these overlap. This is the case in Queshm Island where the Geopark and other protected areas overlap and both lay in the direct neighborhood with a developing zone, enhanced by being a free-trade area.

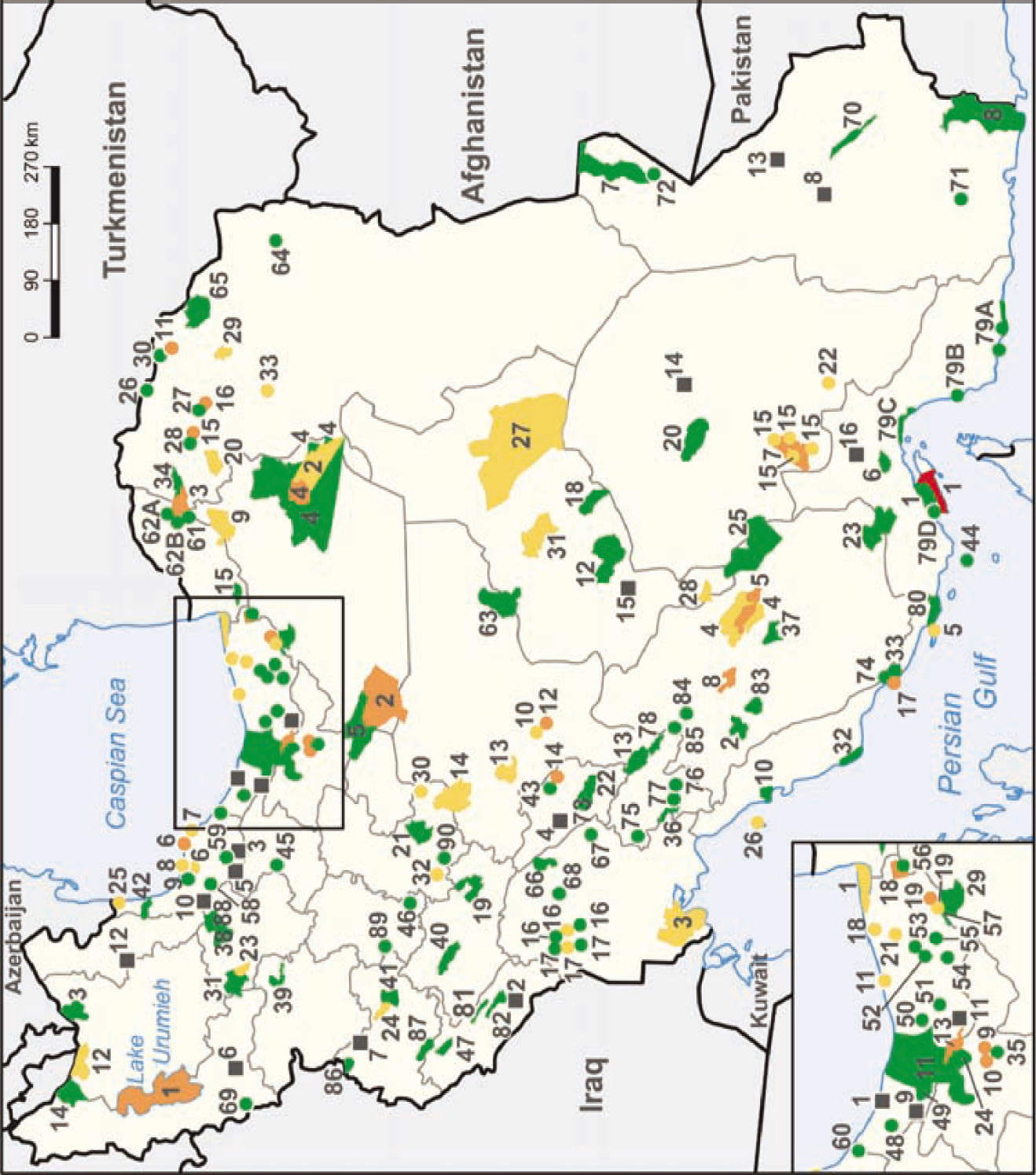

Combining Geoparks with other protection areas seems to be a characteristic of Iranian Geoparks, as many parts of the country are under some type of protection (see Map 1). This web of protected areas can be of help to identify and establish new Geoparks. Yet, the Iranian Geoparks require some standard of nature protection. In other regions, such as Europe, the protection is only formally required when being part of another type of protected area or when intensive sustainable touristic use can be guaranteed (as the case in China).

Currently, Iran offers five different categories for nature protection and the protection of natural and cultural landscapes: Protected Areas, National Parks, Wildlife Refuges, National Nature Monuments and Geoparks. Within these, Geoparks form a relatively small and recent group of protected areas. They have only been established within the last years and often affiliated to other protected zones, therefore Geoparks can both form part of a National Park or include one or more National Nature Monuments. The same holds true for regulations from other countries such as the youngest German Geoparks. Nonetheless the German Geoparks do not have any protective function by themselves so that the Iranian Geoparks seem to be more advanced in this respect. In adjacent countries in the MENA-region, such as Turkey or Yemen, the development of Geoparks is still in a conceptual phase.

The core parts of nature protection in Iran are formed by the so-called Protected Areas. The existing ninety areas are mainly concentrated in the West and the Northwest of the country (see Map 1) with an emphasis on the mountainous areas of the Southeast. As opposed to that, there are relatively few areas of nature protection in the East of the country, where only three Protected Areas (Hamoun, Shila, Geno and Kuh-e-Birk) and two Nature Monuments (Taftan and Cheshmeh- e Gelfeshan-e Pirgel) are found close to the border to Pakistan and Afghanistan. This distribution of areas of nature protection not only represents the eco- and geo-diversity hotspots of the country, but also serves as an indicator for population emphasis and therefore for the necessity to protect geo heritage from its potential users.

←11 | 12→

Map 1: Protected Areas and Geoparks in Iran

By size the most important Protected Area is the Kavir, the area of Touran and the Northern descent of the Alborz mountain range. These three areas also represent the characteristic combination of different categories of nature protection in Iran: Only the Northwest of the Kavir desert is declared “Protected Area” while main parts of the South are acknowledged as National Park. The area of Touran is in a similar position: the main area include Protected Areas as National Parks and a Wildlife Refuge.

←13 | 14→Yet, the Protected Area of the Alborz mountain range illustrates in a drastic manner the disparity between the theoretical status of nature protection and the actual use. The Northern and Central part of the Alborz mountain range as well as the neighboring coast of the Caspian Sea are a highly frequented touristic area for tourists from Teheran and are heavily affected by massive tourism. The tourism development of this area can be divided in different stages, as Ghadami and Mirzaei have shown (chapt. 7, 9 and 15); first settlements where built close to the Caspian Sea, regardless of existing regulation. Today, the central coast zone of Kaspi is almost completely overbuilt so that the coast can hardly be accessed. Meanwhile this trend has extended towards the west in the direction of Gilan and to the east, in the direction of Gorgan. The third phase of construction is marked by the sprawl towards the Northern decent of the Aloborz mountain rage where mainly vacational housing and weekend houses were built within the mountainous area, even within the Protected Area. This nature and landscape destroying phenomenon cannot be deduced to extending form of Beach Tourism but to a specific form of Escape Tourism. Especially the young Tehranean population sees the mountains as an escape from the perceived narrowness of the Iranian capital. This includes the escape from physical factors, such as poor air quality and urban heat as well as social control mechanisms. Many hope to find liberation from the urban stress by escaping to the rural environment (Map 2).

←14 | 15→

Map 2: Geoparks and Geosites in Iran.

←15 | 16→The example of the “National Park Urumieh Lake” shows likewise that the declaration of nature protection zones does not necessarily lead to the implementation of nature or landscape protection. The area of the Urumieh Lake is marked by an ecological catastrophe: Extreme water shortages within the lake are the results of a global climatic change as well as agricultural mismanagement. In this volume, the contribution by Esmail Kahroum from the Ministry of Ecology follows up with the environmental catastrophe that has taken place and has almost resulted in the drying-up of the lake (chapt. 13). This dramatic catastrophe is comparable with the environmental damage from Lake Aral in Uzbekistan (Opp 2004).

Finally, the sustainability of jobs for students in tourism management is discussed by Sadegh Salehi and Mokhtar Naeiji in their case study about Mazandaran, while Sedigeh Loftt, Ayoub Manouchehri and Hassan Ahaar focus on the ability of small and medium scale cities to offer urban services. The latter took the region of Marageh as an example. Quite a sensitive and at the same time very important issue is touched by the article of Ahmad Reza Sheikhi on the role of archeological museums in guiding cultural tourism conceptions. In this regard Iranian Geopark ideas seem to be much more developed than those in other regions such as Europe, especially in Germany, for example, where still a certain concentration on mainly geological aspects can be observed. Thus scientific comparisons of different concepts and developments of Geoparks in Iran and Europe offer the chance of realizing the high potential of combining geological and cultural heritage features in order to provide their preservation for coming generations.

References

Amrikazemi, A. (2010): Atlas of Geopark and Geotourism Resources of Iran. Geoheritage of Iran. Geological Survey of Iran.

Dittmann, A. (2011): Der „Kizilcahamam Camlidere Jeopark” – ein Kooperationsprojekt der Universitaten Giefien und Ankara. In: Rundbrief Geographie, Vol. 232, S. 12-14.

Errami, E., Brocx, M., und V. Semeniuk (eds.) (2015): From Geoheritage to Geoparks. Case Studies from Africa and Beyond. Springer. Heidelberg, New York, London.

Ghadami, M. (2007). Modeling sustainable urban and tourism development, Kelardasht as case study. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Tehran: Tehran.

Mirzaei, R. (2013): Modeling the socioeconomic and environmental impacts of nature-based tourism to the host communities and their support for tourism. http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2013/10085/pdf/MirzaeiRoozbeh_2013_09_25.pdf.

Opp, Ch. (2004): Ursachen und Entwicklung des Aralseesyndroms. In: Opp, Ch. (Hrsg.): Wasserressourcen – Nutzung und Schutz. Marburger Geographische Schriften, Vol. 140: 273-289.

Details

- Pages

- 291

- Year

- 2017

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631702765

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653031829

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631702772

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631644560

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11656

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (June)

- Keywords

- Geographie Kulturgeographie Geopädagogik Nationalparks Naturschutz Ökologie

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2017. 291 pp., 33 b/w ill., 10 coloured ill., 57 b/w tables