English Teaching and New Literacies Pedagogy

Interpreting and Authoring Digital Multimedia Narratives

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Content

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- References

- Chapter 1: Toward a Metalanguage for Multimedia Narrative Interpretation and Authoring Pedagogy: A National Curriculum Perspective from Australia

- Introduction

- Basic Concepts in Systemic Functional Grammar

- SFG-Influenced Metalanguage: Curriculum Requirements and Pedagogic Application

- Differentiating Verb Types and Literary Interpretation in Classroom Work

- The Language of Evaluation: Communicating Personal Stance

- Grammatical Theme: Orienting the Clause in its Context

- Interpreting and Creating Multimodal Texts in Paper and Digital Media

- A Metalanguage Describing the Meaning-Making Resources of Images

- Intermodality

- Conclusion

- References

- Further Reading

- Notes

- Chapter 2: Using Contemporary Picture Books to Explore the Concept of Intermodal Complementarity

- The Nature of Intermodality

- Understanding Image-Text Relationships in the Picture Book Fox

- Discussion of Written Analysis

- Discussion of Visual Analysis

- How Images and Text Work Together

- Conclusion

- References

- Further Reading

- Web Resources

- Chapter 3: Digital Fiction

- Introduction

- Types of Digital Fiction

- Digital Replications of Known Texts

- Digital Enhancements and Embellishments to Known Texts

- Digital Transformations of Known Texts

- Digital Reversionings of Known Texts

- Born Digital Fiction

- Blended Reality Fictions

- The Affordances of Digital Fiction

- Affordance 1: Multimodality

- Affordance 2: Hypertext/Hypermedia

- Affordance 3: Spatiality

- Affordance 4: Interactivity

- Digital Fiction “Done Well”

- Deep Studies of Digital Fiction: 5Haitis

- Conclusion

- References

- Web Resources

- Chapter 4: A Model for Critical Games Literacy

- Why Digital Games and Literacy?

- Games-as-Action

- Actions

- Designs

- Situations

- Games-as-Text

- Knowledge About Games

- “Me” as Game Player

- The World Around the Game

- Learning through Games

- The Model in Combination

- References

- Chapter 5: Enabling Students to be Effective Multimodal Authors

- Introduction

- Grammatical Design

- Grammatical Design Applied to 3D Multimodal Authoring

- A Pedagogy of Multimodal Authoring

- Influences on Teaching Approaches

- Introducing Learners to Design Elements through Vdddr

- Independent Construction of a Multimodal Text

- The Planning Phase

- A Grammatical Design Approach to Assessment

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1: Sample Story Outline for a Narrative

- Appendix 2: Sample Character Profile

- Appendix 3: Sample Storyboard for a Simple Narrative

- Notes

- References

- Further Reading

- Chapter 6: the Image/Language Interface in Picture Books as Animated Films: A Focus for New Narrative Interpretation and Composition Pedagogies

- Introduction

- Images of Inclusive Contact

- Rear View Images

- The Book and Animated Movie Versions of the Lost Thing: A Focus for Comparison

- The Image/Language Interface and Audience Engagement: Appreciation or Empathy

- Discovering the Lost Thing and Asking for Help

- Feeding the Lost Thing

- The Federal Department of Odds and Ends

- Saying Goodbye: Indifference, Involvement, and Intensification

- Coda: A Weird, Sad, Lost Sort of Look

- Interpretive Positioning through the Image/Language Interface: From Comprehending to Composing

- References

- Chapter 7: Using Focalisation Choices to Manipulate Audience Viewpoint in 3-D Animation Narratives: What do Student Authors Need to Know?

- Introduction

- 3-D Animation and the Moving Image Mode

- Moving Image Semiotic Resources

- Moving Image and Camera

- Moving Image and Editing

- Focalisation

- Three Components of Focalisation

- Designing Interpersonal Relationships

- Register Theory and Metafunctions

- Interpersonal Meaning

- Introducing the System Network

- Metalanguage

- Systems

- Focalisation System Network

- Research Method and Example

- Choice of Focaliser

- Unmediated Focalisation

- Mediated Focalisation

- Along-with-Character Focalisation

- As Character Focalisation

- Inscribed or Inferred? Realising “As Character” or First-Person Focalisation

- Inscribed Meaning

- Inferred Meaning

- Choice of Focalised Subject

- Focalised Subject and Moving Image Semiotic Resources

- Focalising Choices

- Social Distance System

- Proximity

- Contact System

- Attitude System

- Involvement

- Power

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgment

- Notes

- References

- Web Resource

- Further Reading

- Chapter 8: Social Media, Education, and Contentious Literacies

- Introduction

- Blogging as a New Literacy Practice

- Context and Methodology

- Analysis and Findings

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter 9: Teaching Inanimate Alice

- Introduction

- Ros and Jenny: Using Inanimate Alice to Teach New Literacies

- Our Teaching Rationale

- Why Inanimate Alice?

- Planning Considerations

- Student Reversioning of Inanimate Alice

- Conclusion

- References

- Further Reading

- Web Resources

- Chapter 10: Empowering Older Adolescents as Authors: Multiliteracies, Metalanguage, and Multimodal Versions of Literary Narratives

- Introduction

- Impetus and Inspiration: Multiliteracies, Transformative Teaching and Learning

- Using Multimodal Resources and Digital Technologies for Writing Stimuli

- Using Multiple Modes for Analyzing Film Trailers

- Conclusion

- References

- Further Reading

- Web Resources

- Chapter 11: Augmented Reality in the English Classroom

- Introduction

- What is Augmented Reality?

- Mobile Augmented Reality

- How has ar been used for Educational Purposes?

- Augmented Reality Storytelling

- Zooburst

- The Magicbook

- Locative Storytelling

- A Pedagogy for Locative Storytelling

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- Notes

- References

- Further Reading

- Web Resources

- Chapter 12: Virtual Macbeth: Using Virtual Worlds to Explore Literary Texts

- Background

- Pedagogical Framework

- Participation and Student Work

- Conclusion

- References

- Further Reading

- Web Resources

- Contributors

- Index

← VI | VII → Acknowledgments

The editors would like to acknowledge the Australia National Council of Deans of Education whose Commonwealth Government innovation funding supported a local Teaching Teachers for the Future (TFF) project at the University of Tasmania. The TTF project was designed to explore how new forms of digital multimedia technology can be infused into the teaching of English. This edited book derives from the extensive and intensive work with high-profile international teacher educators and researchers as well as with local and international teachers as a result of the funding granted for this project.

To publishers Allen and Unwin, thank you for granting permission for use of artwork from Margaret Wild and Ron Brooks’s picture book Fox.

We thank Passion Pictures Australia Pty. Ltd. for permission to include still images from the animated movie The Lost Thing.

We would also like to thank the journal editors of e-Learning and Digital Media for allowing us to use a version of the article “A Model for Critical Games Literacy” (E–Learning and Digital Media, Volume 10, Number 1, 2013) in our book.

Finally, we thank Damon Thomas for the time spent formatting and checking references across all chapters. ← VII | VIII →

← VIII | IX → Preface

LEN UNSWORTH & ANGELA THOMAS

As the use of sophisticated digital multimedia communication software is becoming increasingly routine in the lives of many children and young people, school systems, teacher education, and curriculum authorities need to adjust to meet the needs of all students in the context of rapidly changing forms of literacy. This has recently been brought into sharp focus in Australia with the release of the new national curriculum in English. In both primary and secondary schools, students will now be expected to demonstrate competence in digital multimodal literacy. For example, the new national curriculum in English (ACARA, 2010) will require Year 4 students to

Explore the effect of choices when framing an image, placement of elements in the image, and salience on composition of still and moving images in a range of types of texts.

In Year 6 students will be required to

Plan, draft and publish imaginative, informative and persuasive texts, choosing and experimenting with text structures, language features, images and digital resources appropriate to purpose and audience.

And in Year 8 they will be expected to

Explore and explain the ways authors combine different modes and media in creating texts, and the impact of these choices on the viewer/listener.

← IX | X → Such requirements reflect international longstanding and ongoing calls in the UK (Jewitt, 2002, 2006; Kress, 1995; Marsh, 2011) and the United States (Calvo, O’Rourke, Jones, Yacef, & Reimann, 2011; Gee, 2003; Lemke, 2006) for changes in English and literacy education to address the changing educational needs of a rapidly evolving and essentially digital multimedia communication world. However, it is also clear that internationally a significant proportion of teachers and teacher educators will need a great deal of professional development to enable them to address the implementation of these curriculum requirements.

The distinctive emphasis of the book is on new forms of digital multimedia narrative and the development of students as effective multimedia authors from the relatively early years of primary school through secondary school. This addresses a gaping chasm between the growing participation of children and adolescents in a variety of forms of multimedia authoring outside of school and the hegemonic mono-modal writing pedagogy of the past that dominates most students’ experience of textual composition at school. This book will help prospective and practicing teachers to see how they can contribute to changing pedagogic practice and that the incorporation of multimedia authoring has both a theoretical and strong practical basis in the experience of those who are already involved in enacting this change in primary and secondary schools.

The first four chapters set the scene and explore the necessary awareness and fundamental knowledge bases for innovative practice. These chapters indicate the explicit, systematic knowledge about the meaning-making resources of image and language, separately and interactively, that teachers and students can draw on to enhance their effectiveness as multimodal authors. The subsequent chapters deal with the possibilities of new forms of storytelling for young children and the practical pedagogies of multimodal authoring in the primary school. The four chapters following these deal with new forms of narrative experience in middle school and secondary school classrooms, including emerging forms of new narrative experience based on Augmented Reality Technology, which enables mobile technology to overlay virtual content onto real-world contexts, blending the actual and the virtual in new forms of textual experience. What is important to recognize is that, although there are four chapters that focus on the classroom experience of this work in the primary school and the secondary school, in each case the broad potential of what is discussed can be transferred across levels of schooling.

English teachers will recognize the valuing of literature and appreciate the practical pedagogy and fostering of creativity as students are encouraged to explore new forms of narrative in the context of developing expertise in knowing and deploying the meaning-making resources of language as well as other digital multimedia. We expect this book to be valued not only as a course text but also as a professional resource for primary school and secondary school teachers.

← X | XI → REFERENCES

ACARA. (2010). The Australian curriculum: English. Retrieved from http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/English/Curriculum/F-10

Calvo, R., O’Rourke, S., Jones, J., Yacef, K., & Reimann, P. (2011). Collaborative writing support tools on the cloud. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 4(1), 88–97.

Gee, J. (2003). What computer games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jewitt, C. (2002). The move from page to screen: The multimodal reshaping of school English. Visual Communication, 1(2), 171–196.

Jewitt, C. (2006). Technology, literacy and learning: A multimodal approach. London: Routledge.

Kress, G. (1995). Writing the future: English and the making of a culture of innovation. Sheffield: National Association of Teachers of English.

Lemke, J. (2006). Towards critical multimedia literacy: Technology, research and politics. In M. McKenna, L. Labbo, R. Kieffer, & D. Reinking (Eds.), International handbook of literacy and technology (Vol. 2, pp. 3–14). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Marsh, J. (2011). Young children’s literacy practices in a virtual world: Establishing an online interaction order. Reading Research Quarterly, 46(2), 101–118.← XI | XII →

← XII | 1 → CHAPTER ONE

Toward a Metalanguage for Multimedia Narrative Interpretation and Authoring Pedagogy

A National Curriculum Perspective from Australia

LEN UNSWORTH

INTRODUCTION

In the current and evolving digital multimedia communication age a fundamental challenge for the English curriculum, and for teachers, is to embrace, as a pedagogic priority, the development of students’ understanding of new forms of multimodal grammar. Developing students’ explicit understanding of how meanings are made within distinct semiotic systems such as language, image, movement, music and sound, as well as their understanding of how these resources are articulated in making complex meanings in multimodal texts, is a crucial aspect of a socially responsible English curriculum and pedagogy concerned with equity and effectiveness in preparing students for the constantly changing communication contexts they are living in. This metasemiotic understanding of multiple, integrated, meaning-making resources is fundamental to effective new literacies pedagogies. What we are concerned with here goes beyond simply using or comprehending language (and/or images and other semiotic resources) effectively. It concerns building students’ conscious awareness of why particular linguistic or visual semiotic choices are effective in different contexts through developing their knowledge of the systems of meaning-making options within language or images or other semiotics. This metasemiotic understanding requires a metalanguage that describes how linguistic forms and visual features of images and aspects ← 1 | 2 → of other semiotic systems relate to meaning, both within and across the different semiotics in multimodal texts (New London Group, 1996, 2000). The chapter seeks to further promote the development of an intermodal metalanguage, such as that proposed by the New London Group based on systemic functional linguistic (SFL) accounts of grammar (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004) and genre (Martin, 1992; Martin & Rose, 2008) and extrapolations from this work to related social semiotic descriptions of images (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006), three-dimensional art (O’Toole, 1994, 2004), music (van Leeuwen, 1999), gesture (Martinec, 2000, 2004), and film (van Leeuwen, 1991, 1996). The systemic functional linguistic work on grammar and genre as well as the work on images have become significantly incorporated into literacy research and pedagogic practice in Australia and internationally (Achugar, Schleppegrell, & Oteíza, 2007; Christie, 1989, 2005; Lemke, 1989, 1990, 1998, 2002, 2006; Love, 1996, 2000; Love, Pigdon, Baker, & Hamston, 2002; Macken-Horarik, 1996, 2008; Macken-Horarik & Adoniou, 2008; Macken-Horarik & Morgan, 2011; Schleppegrell, 2004; Schleppegrell, Achugar, & Oteíza, 2004). It is now strongly reflected in the new National Curriculum in English for Australian schools from the beginning of schooling to Year 10 (ACARA, 2012).

This chapter shows how the new Australian Curriculum: English (ACE) (ACARA, 2012) represents an innovative, albeit partial, introduction of metalanguage for verbal and visual grammar, clearly largely derived from SFL and related work (although not acknowledged as such). First, some basic concepts in SFL descriptions of grammar are briefly outlined. Then attention is drawn to the strong reflection of these SFL grammatical descriptions in the explicit requirements for the use of metalanguage as set out in the “Content Descriptions” of the Australian Curriculum: English (ACARA, 2012), which specify “the knowledge, understanding, skills and processes that teachers are expected to teach and students are expected to learn” (p. 5). Examples of the metalanguage required at different grade levels that distinctively reflect SFL descriptions will be identified and brief illustrations of their practical application in teaching narrative interpretation and text creation will be provided. The next section of the chapter shows the significant ACE emphasis on developing students’ interpretation and creation of multimodal texts in paper and digital media through a sampling of content descriptions at different grade levels. The focus is then on the nature, extent, and distribution of the metalanguage required in the ACE content descriptions describing the meaning-making resources of images, and the similarity of this metalanguage to the grammar of visual design extrapolated from systemic functional linguistics (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006). The ways in which images and language interact to construct meaning is also emphasized in the ACE as an important focus for student learning, and recent research further developing ← 2 | 3 → systemic functional initiatives in this area of intermodality are also briefly discussed in this chapter.

In concluding, the chapter suggests that while there are clear curricula and pedagogic advantages to the incorporation of systemic functional semiotic perspectives, determining the nature and extent of the metalanguage(s) apposite for supporting new literacies pedagogies at the various stages of schooling requires a much clearer, consistent, and comprehensive theoretical basis underpinning the curriculum (Unsworth, 2006, 2008) as well as substantial classroom-based research (Macken-Horarik, Love, & Unsworth, 2011). In progressing the discussion of metalanguage we will seek to address the following three key questions:

1. How can descriptions of the knowledge about language (KAL) required in school curricula be articulated with corresponding knowledge about the meaning-making resources of images to provide the metalanguage necessary to support digital multimodal literacy pedagogy?

2. How can such a metalanguage facilitate multimedia narrative interpretation and authoring pedagogy?

3. How can official curricula enhance new literacies development through more explicit and comprehensive inclusion of metalanguage adopted from multimodal semiotic theory?

BASIC CONCEPTS IN SYSTEMIC FUNCTIONAL GRAMMAR

Only a sketch of some basic concepts of systemic functional grammar (SFG) is possible here (for an accessible, chapter-length summary framework for SFG see Ravelli, 2000; Unsworth, 2001; and Williams, 1993. For book-length introductions to SFG for teachers see Butt, Fahey, Feez, Spinks, & Yallop, 2000; Droga & Humphrey, 2003; Humphrey, Love, & Droga, 2011). SFG proposes that all clauses in all texts simultaneously construct three types of meanings:

• Experiential meanings involve the representation of objects, events, and the circumstances of their relations

• Interpersonal meanings involve the nature of the relationships among the interactive participants

• Textual meanings deal with the ways in which language coheres to form texts

Experiential meanings are realized grammatically by Participants, Processes, and Circumstances of various kinds. Circumstances correspond to what is traditionally ← 3 | 4 → known as adverbs and adverbial phrases. Processes correspond to the verbal group, but Processes are semantically differentiated. Material Processes (action verbs), for example, express actions or events (such as walk, sit, or travel), while Mental Processes (sensing verbs) deal with thinking, feeling, and perceiving (understand, detest, see) and Verbal Processes deal with saying of various kinds (demand, shout, plead). Relational Processes link a Participant with an Attribute (She is tall; He appears tired) or identify or equate two Participants (She is the School Captain; Cu symbolizes copper.) These different kinds of Processes have their own specific categories of participants. Material Processes, for example, entail Actors (those carrying out the process) and Goals (those to whom the action is directed), while Mental Processes entail a Sensor and a Phenomenon. Relational processes that are attributive link a Carrier to its Attribute and if they are identifying they equate a Token and a Value.

Interpersonal meanings are realized by the mood and modality systems. Much of this aspect of SFG is familiar to those with experience of more traditional grammars. Statements are realized by declarative mood where the ordering within the clause is Subject followed by the Finite Verb (Grandad does enjoy his soup). Questions are realized by the interrogative mood where the ordering of Subject and Finite Verb is reversed (Does Grandad enjoy his soup?). The modal verbs (can, should, must, etc.) indicate degrees of obligation or inclination and modal adverbs such as frequently, probably, and certainly enable personal stance to be communicated through negotiating the semantic space between yes and no.

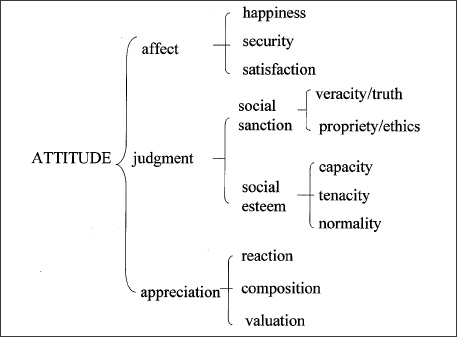

The personal stance aspect of interpersonal meaning was developed further in the Appraisal framework for conceptualizing and analyzing attitude (Martin & White, 2005). The framework has also been made available in a form easily accessible to teachers and students (Droga & Humphrey, 2003). In this framework, shown in Figure 1.1, attitude is subdivided into the categories of affect, appreciation, and judgment. Affect refers to the expression of feelings, which can be positive or negative, and may be descriptions of emotional states (e.g., happy) or behaviors that indicate an emotional state (e.g., crying). Subcategories of affect are happiness, security, and satisfaction. Appreciation relates to evaluations of objects, events, or states of affairs and is further subdivided into reaction, composition, and valuation. Reaction involves the emotional impact of the phenomenon (e.g., thrilling, boring, enchanting, depressing). Composition refers to the form of an object (e.g., coherent, balanced, haphazard), and valuation refers to the significance of the phenomenon (e.g., groundbreaking, inconsequential). Judgment can refer to assessments of someone’s capacities (brilliant, slow), their dependability (tireless, courageous, rash), or their relative normality (regular, weird). Judgment can also refer to someone’s truthfulness (frank, manipulative) and ethics (just, cruel, corrupt).

Fig 1.1. The Appraisal Framework, derived from Martin and Rose (2007).

Textual meanings are realized in part by the Theme/Rheme system. The Theme is the point of departure (Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004, p.64), orienting the clause in its context, and is the element that is in first position. This is usually the Subject (“The weather is mild in Australia”), but another element, such as a Circumstance (adverbial element) could be placed in Theme position (“In Australia the weather is mild”). This is not as common and is likely to occur more frequently in more formal written language than in informal spoken language. When some experiential element other than the Subject is placed in first position in a clause, it is referred to as a Marked Theme, in that it draws more attention due to its relatively less frequent use.

The three different grammatical systems realize the three main types of meaning simultaneously. For example, in the sentence, “The leader usually carries the flag on parade,” the first element in the clause, The leader, is the Theme from the textual perspective. From the experiential perspective The leader is also the Actor (the doer of the action) and from the interpersonal perspective, in the mood system, The leader is the Subject. We could change the Theme—“On parade the leader usually carries the flag”—so the orientation of the clause in its context is different. Now The leader is not the Theme, but remains the Actor in experiential terms, and the Subject in interpersonal terms.

← 5 | 6 → SFG-INFLUENCED METALANGUAGE: CURRICULUM REQUIREMENTS AND PEDAGOGIC APPLICATION

After the Foundation year, which is a preparatory or kindergarten year, the requirement for explicit learning of knowledge about language occurs from Year 1 of the Australian Curriculum: English (ACE). For example, students in Year 1 are expected to know that “a basic clause represents: a happening or a state (verb), who or what is involved (noun group/phrase), and the surrounding circumstances (adverb group/phrase).” Year 1 students are also expected to “understand that the purposes texts serve shape their structure in predictable ways.” In addition, the students need to become “familiar with the typical stages of types of text including recount and procedure” (ACARA, 2012, p. 28). Progressively advanced knowledge expectations of grammar and genre permeate the curriculum, and the terminological formulation of most of these will be recognizable to those familiar with traditional school grammar. The examples of “Content Descriptions” to be discussed here illustrate the distinctive SFL influence on the approach to grammar. The grammatical construction of experiential meaning is illustrated by the approach to verbs in Year 3. An example of the SFL approach to the grammatical construction of textual meaning is shown with the introduction of grammatical “Theme” in Year 5. The grammatical resources for constructing interpersonal meaning are illustrated in the Year 6 requirements regarding modal verbs and adverbs and in the Year 7 requirements regarding resources for expressing evaluative meanings. It is expected that students will develop explicit knowledge of such grammatical concepts and use them to discuss their interpretation and creation of multimodal texts. This expectation is made clear in the curriculum. In Year 4, for example, Content Description (ACARA, 2012, p. 52)1 states that students will “use metalanguage to describe the effects of ideas, text structures and language features of literary texts” (ACARA, 2012, p. 52) and in Year 5 students are required to “present a point of view about particular literary texts using appropriate metalanguage” (ACELT1609) and “use metalanguage to describe the effects of ideas, text structures and language features of literary texts” (ACELT1604) (ACARA, 2012, p. 59).

Details

- Pages

- XII, 272

- Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453913116

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454191599

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454191582

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433119071

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433119064

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1311-6

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (December)

- Keywords

- Multimedia Digital narrative Practical pedagogy Literacy practice

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. 272 pp., num. ill. and fig.