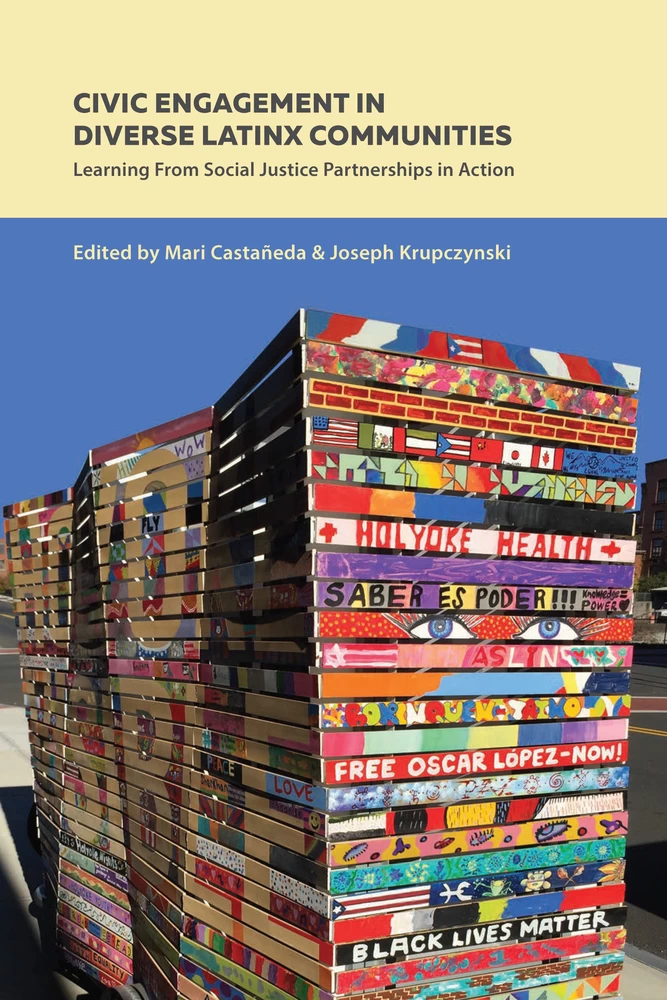

Civic Engagement in Diverse Latinx Communities

Learning From Social Justice Partnerships in Action

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance Praise for Civic Engagement in Diverse Latinx Communities

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Toward a Latinx Community-Academic Praxis of Civic Engagement (Mari Castañeda / Joseph Krupczynski)

- The Rise of Civic Engagement and Community Service-Learning

- The Emergence of a Latinx Community-Academic Praxis

- Note

- References

- Section I: Rethinking Community and Civic Engagement

- 1. Civic Engagement: Learning From Teaching Community Praxis (Antonieta Mercado)

- Intersectional Roles: From the Community to the Classroom

- Practices of Tequio as Bridgework in the Classroom

- Friendship Park

- Day of the Dead Altar

- Community Advocacy

- Conclusion

- References

- 2. Imagining a Nueva Casita: Puerto Rican Subjectivities and the Space of the “In-between” on an Urban Farm in Western Massachusetts (Joseph Krupczynski)

- Theorizing Engagement as “In-between”

- Contextualizing Holyoke, MA

- Urban Agriculture in Holyoke

- The Nueva Casita Project With Nuestras Raices

- Conclusion

- References

- 3. Subject-Heading or Social Justice Solidarity? Civic Engagement Practices of Latinx Undocumented Immigrant Students (Claudia A. Evans-Zepeda)

- Connecting Critical Pedagogy, Civic Engagement, and Latina/o Critical Communication

- Creating CoFIRED

- Centralizing the Latino Experience

- Acknowledge and Address the Racism Faced by the Latina/o Community

- Resist Literacy-Colorblind Language/Rhetoric Toward Latina/os

- Deploy Decolonizing Methodological Approaches

- Promote a Social Justice Dimension

- Reflections on Operationalizing LatCritComm on Campus

- Notes

- References

- 4. Keeping It Real: Bridging U.S. Latino/a Literature and Community Through Student Engagement (Marisel Moreno)

- How to Set Your CBL Course Up for Success

- Reflect on Your Course and How It Would Benefit From Linking It to the Community

- Be Selective When Choosing a Community Partner

- Prepare Your Students and Help Them “Connect the Dots”

- Remind Yourself That There’s Not One “Right” Way to Do CBL

- Best Practices in the Classroom

- Conclusion

- References

- 5. Public Humanities and Community-Engaged Learning: Building Strategies for Undergraduate Research and Civic Engagement (Clara Román-Odio / Patricia Mota / Amelia Dunnell)

- Latinos in Rural America: Stories of Cultural Heritage, Values, and Aspirations

- Funding

- Institutional Requirements and Training

- Community Outreach

- Participant Interviews and Analysis of Materials

- Research and Oral History Outcomes

- Demographic Background

- Analysis of Interviews

- Circular Journeys

- A Sense of Place and Displacement

- Values and Culture

- Bicultural Identities

- (Hyper)Visibility/Invisibility

- Dreams and Aspirations

- CEL as a Vehicle for Civic Action

- Community Response to LiRA

- Concluding Thoughts

- Notes

- References

- Section II: Community Voices and the Politics of Place

- 6. Community as a Campus: From “Problems” to Possibilities in Latinx Communities (Jonathan Rosa)

- Conceptualizing and Approaching Communities as Campuses

- The VOCES Project: Voicing Our Community in English and Spanish

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 7. Motherists’ Pedagogies of Cultural Citizenship: Claiming Rights and Space in a Xenophobic Era (Judith Flores Carmona)

- Pedagogies of the Home

- Cultural Citizenship and Chicana/Latina Feminisms

- Latina Mothers’ Testimonios and Pedagogies of Cultural Citizenship

- Conclusion

- Lessons Learned

- Notes

- References

- 8. Responsibility, Reciprocity, and Respect: Storytelling as a Means of University-Community Engagement (J. Estrella Torrez)

- Civic Engagement in the University: Responsibility

- Storytelling Is Our Medicine: Reciprocity

- Understanding My Place: Respect

- Conclusion

- References

- 9. Arizona-Sonora 360: Examining and Teaching Contested Moral Geographies Along the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands (Celeste González de Bustamante)

- Situating Arizona’s Political Landscape

- Conceptual Frameworks for Community-Based and Community Service Learning at the U.S.-Mexico Border

- Faculty of Color

- Community Engagement and the Contradictions of Academic Capitalism

- Critical Borderlands Pedagogy and the Media

- Moral Geography

- Creating Counter Cartographies

- Critical Borderlands Pedagogy and Community Action

- Migrahack, March 22–25, 2015

- Security 360: Mapping Militarization of Ambos Nogales

- Student Experiences and Learning Outcomes

- Undergraduates: Overall Experiences

- Graduate Students: Overall Experiences

- Opportunities, Challenges, and Limitations

- Critical Borderlands Pedagogy and Moral Geography

- Community Engagement in the Age of Academic Capitalism

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 10. Saber es Poder: Teaching and Learning About Social Inequality in a New England Latin@ Community (Ginetta E. B. Candelario)

- When and Where I Enter

- We Must Stare Into the Ruins—Bravely and Resolutely

- And We Must See

- And Then We Must Act

- From Saber to Poder

- References

- Section III: Expanding the Media and Cultural Power of Communities

- 11. Media Literacy as Civic Engagement (Jillian M. Báez)

- Media Literacy With Latina Girls in a Community-Based Organization

- Media Literacy Among Latina/o College Students

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- 12. “I Exist Because You Exist”: Teaching History and Supporting Student Engagement via Bilingual Community Journalism (Katynka Z. Martínez)

- Community Journalism and Community Service

- Newspapers and the History of Latinas/Latinos in California

- Student Voices Amid a Digital Gold Rush

- I Exist Because You Exist: Continuing the Dialogue Through El Tecolote

- References

- 13. Hashtag Jóvenes Latinos: Teaching Civic Advocacy Journalism in Glocal Contexts (Jessica Retis)

- Civic Advocacy Journalism: Why Labels?

- Teaching Journalism From an Inclusive Perspective

- Critical Pedagogy in the Analysis of Latinos and the Media

- Community Organizations as Main Sources of Information: Video Reporting

- With, for, and by Young Latinos

- Notes

- References

- 14. Chicana/o Media Pedagogies: How Activism and Engagement Transform Student of Color Journalists (Sonya M. Alemán)

- The Venceremos Contributors

- Pedagogy of Counter-News-Story

- Measuring Student Impact

- Media Consumption and Civic Engagement

- News Consumption

- Social Justice-Based Civic Engagement

- Implications

- Note

- References

- 15. Lessons From Migrant Youth: Digital Storytelling and the Engaged Humanities in Springfield, MA (Rogelio Miñana)

- The Promoting Bilingual Literacy Project

- Digital Storytelling in Springfield, Massachusetts: A Brief Overview

- Engaged Scholarship: A Technology-Enhanced and Community-Based Methodology

- Learning From the Community (and Our Mistakes)

- Project-Based, Open-Ended, and Engaged Design

- Interdisciplinary Collaborations

- Action Research and True Partnership

- Conclusion: Crisis or Opportunity for the Engaged Humanities?

- Notes

- References

- Contributors

- Editors

- Section I

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Section II

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Section III

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Chapter 15

- Index

- Series index

We would first like to acknowledge the scholar-activist authors who contributed to this edited collection. It is their commitment, reciprocity, risk-taking, and love for Latinx communities that is transforming higher education, civic engagement, and community-based relationships. We are so honored to be part of your journey and we thank you for your willingness to be part of ours. Secondly, we want to recognize our wonderful colleagues and dearest friends at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst for their magnificent support and encouragement, especially in the Department of Communication, the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, the Center for Latin American, Caribbean and Latina/o Studies, the College of Humanities and Fine Arts, the Center for Design Engagement, the Department of Architecture, and Civic Engagement and Service Learning. We also want to say mil gracias to NECLS (New England Consortium of Latina/o Studies) and the mujeres online writing group for continually reminding us that scholarly production is an important form of liberation and transformation. Similarly, thank you very much to Peter Lang Publishers, particularly Tim Swenarton and Sarah Bode as well as Yolanda Medina and Margarita Machado-Casas (series editors for Critical Studies of Latina/os in the Americas) for believing in this book project and ushering its existence. Last but not least, we want to give a big shout out to our familias, whose unconditional love and dedication to social justice movements energizes us every day. We especially want to thank our son, Miguel Angel Paredes, an emerging 21st century leader and community-oriented artist-activist (a.k.a. Tuzko), for always motivating and inspiring us to create the art and world we want to see!

With love, deep respect, and gratitude for all, Mari Castañeda and Joseph Krupczynski, Amherst, MA.

Introduction: Toward a Latinx Community-Academic Praxis of Civic Engagement

Latinx1 communities are powerful sources of knowledge. Unlike the dominant media images, emboldened by the hateful rhetoric of the current U.S. administration, that portray these communities as sites of violence, degeneration or illegality, this book aims to show how faculty and students at a range of universities and colleges across the United States are learning from, and engaging with Latina/o communities through social justice partnerships, while concurrently disrupting the fallacious notions that circulate about people of Latin American and Caribbean descent. Cumulatively, the chapters in this book point toward a Latinx community-academic praxis that challenges how knowledge is created, how civic engagement is practiced, and the application of community service-learning in higher education, especially at a moment when racial/ethnic communities are persistently challenged politically, economically and socially. The U.S. Census predicts that by the year 2050, the diverse Latinx population will double in size and constitute nearly 30% of all people residing and working in the United States (Colby & Ortman, 2015). Presently, 1 out of 4 children born in the U.S. are of Latina/Hispanic descent. Demographic statistics and socio-cultural research confirm that the Latinx diaspora will undoubtedly impact the future of American politics, economics, cultural landscapes, and educational institutions (Kochhar, Suro, & Tafoya, 2005; Suro & Singer, 2002). Yet the nature and contour of that influence will be greatly dependent on the general population’s perception and treatment of Latinos and the opportunities available to harness the social and cultural assets that will shape their participation in civil society and the public sphere. ← 1 | 2 →

Similarly, it is important to examine how the racial, economic, and cultural diversity of Latinx communities have affected the ways in which the population is (mis)understood and its contributions to public life are (un)acknowledged in the U.S. (Arreola, 2004; Diaz & Torres, 2012; Geron, 2005). In an effort to disrupt racist and problematic perceptions of U.S. Latinos while also collaborating with local communities to create opportunities for empowerment and engagement, the scholars in this collection have developed social justice oriented courses and research projects in a wide array of fields that link college student learning with civic engagement and transformative community movements. Working in communities is not a new practice for university faculty committed to social justice, especially those rooted in Latinx/Chicana studies, African American studies, and ethnic studies. These fields were in fact the result of community organizing and scholar-activists demanding that their institutions create spaces where issues and concerns of underrepresented populations could be taken seriously and critically examined (De la Torre, 1993; Lowe, 1996; Pérez, 1999; Rojas, 2007; Saldívar, 1997; Sandoval, 2000).

The surge in civic engagement and community-based learning at colleges and universities has created new pedagogies and creative opportunities to engage with communities of color. Civic Engagement in Diverse Latinx Communities: Learning from Social Justice Partnerships in Action brings together excellent examples of community-academic partnerships in Latinx communities that include social justice approaches to civic engagement and community service-learning in a wide variety of fields such as media studies, architecture, literature, education, sociology, anthropology and journalism. Their combined experience in community-based teaching as well as their exceptional understanding of social justice pedagogies makes this collection a trove of insights with lessons learned from diverse Latino communities that can also greatly inform student learning and local community partnerships. Building upon the best practices from scholarship in civic engagement, community service-learning, Latina/Chicana/o/x studies, indigenous studies, community studies, intersectional postcolonial/decolonial feminism, and communication/media studies, the authors demonstrate what is possible through civic engagement by drawing on a Latinx community-academic praxis.

In the past several years, several monographs have been published that address civic engagement and community service-learning as key themes for educational institutions, policy makers, community-based organizations and cultural/economic sectors seeking to connect and work with local and global communities as well as challenge historical social relations of exploitation (see Dostilio, 2017; Post, Ward, Longo, & Saltmarsh, 2016; Stoecker, 2016). Although we build on this past work, there are key differences between what ← 2 | 3 → those book volumes attempt to address versus what our collection is aiming to do through its emphasis on Latinx community-academic praxis. First, we firmly believe in the importance of highlighting Latina/o communities as specific sites of creative and dynamic civic engagement and thus build off similar work (see Pérez, Espinoza, Ramos, Coronado, & Cortes, 2010). This volume gives voice to social justice community-academic projects in order to learn from and bear witness to the lived (transnational) experiences of Latinos across the United States. It aims to shift the conversation about community-university partnerships as something where students “do good” for a community, towards a Latinx community-academic praxis that emphasizes social justice partnerships in action, which aim to critically engage with the multiple intersections of oppression (Castañeda, 2008).

Secondly, the scholar-activists in this collection are partnering with Latina/o communities, sometimes under extraordinary circumstances, in an effort to rethink civic engagement practices that center the decolonization of knowledge and a critique of the ways in which color-blind racism can affect student learning. By including elements of testimonio—personal narrative and autoethnography—into the essays, the authors lay bare their presence in a collaboration that aims to address the multiple issues diverse Latinx communities are facing. Testimonio also provides the opportunity to discuss theoretically and empirically the racialized and labor conditions of a pedagogically-based, social justice oriented civic engagement. Thirdly, as the political economy of academic institutions shift towards corporate-based models of teaching, in both explicit and subtle ways, it is critical to ascertain how community-academic partnerships will be affected by these structural-cultural changes. Many of the chapters include pedagogical solutions for creating more community engaged institutions of higher learning in order to change the exclusiveness of the Ivory Tower and support the communities that are changing the social and cultural life of the U.S.

Ultimately, this collection demonstrates that documenting personal experiences in the classroom and in communities is a powerful tool for the production of new knowledge and frameworks of understanding (Burciaga & Cruz Navarro, 2015). Lastly, by collectively emphasizing the possibilities of a critical civic engagement the authors are contributing to a social justice epistemology that aims to investigate and develop new praxis for how to engage with diverse communities in the 21st century. As the chapters in this volume demonstrate, Latinos are material and active subjects with historically specific experiences that must be understood and recognized within local and transglocal contexts. Diverse Latino communities are not stereotypical discursive reproductions, but embodied material and cultural agents who are producing ← 3 | 4 → knowledge and making history, albeit within conditions not entirely of their own making. Ultimately, collectively, we aim to ask, how do we make higher education more responsive to local and regional community needs through reciprocity and with respect to different ways of knowing and learning? In this vein, and in an effort to practice the principles of Chicana/Latinx feminist decolonial methods, many authors engage with the writing practice of testimonio in order to bear witness and develop insight and theoretical connections between their experiences as teachers in the classroom, partners in communities, and activists in civil society. Unlike some of the dominant narratives about civic engagement and service-learning within communities of color, we aim to challenge the deficit models often associated with Latina/o peoples and create new forms of understanding of what is possible when social justice partnerships are put into action.

With this in mind, we use the term Latinx as well as Latina/o, Latino and Latinos and other specific group names such as Chicana/o, Mexican-American and Puerto Rican throughout the book in an effort to be as inclusive as possible. These communities, as many others of color, have also historically experienced coercion with regards to sexual and gender identities. The term Latinx emerged from diverse Latina/o activists and educators arguing that despite mainstream narrow understandings of Latinidad, there needed to be a broadened inclusion of sexual and gender identities within racial, ethnic and cultural positionalities. Thus, this edited collection—Civic Engagement in Diverse Latinx Communities: Learning from Social Justice Partnerships in Action—includes a variety of terminologies currently used to describe diverse Latino communities, sometimes interchangeably, and highlights Latinx in the book title in order to build bridges between history, contemporary identities, and the transcultural and political power of global south communities to claim space and voice their engaged presence.

The Rise of Civic Engagement and Community Service-Learning

According to the Association of Colleges and Universities, “in this turbulent and dynamic century, our nation’s diverse democracy and interdependent global community require a more informed, engaged, and socially responsible citizenry. Both educators and employers agree that personal and social responsibility should be core elements of a 21st century education if our world is to thrive” (AACU, 2016, n.p.). Indeed, preparing students and communities for the social transformations across the Americas and around the globe is an important part of higher education. The expansion of organizations focusing ← 4 | 5 → on service-learning and community-based research such Campus Compact, Teach for America, ServiceCorps, AmeriCorp, and PeaceCorps point to growing appeal of the civic engagement capacity of young adults. Communities can be positively impacted by the participation of emerging leaders while also developing a long-lasting engagement with civic life, especially within and beyond local communities (Saltmarsh, 1996, 1997). Yet it is important to note that not all forms of civic engagement, particularly at universities and colleges, are effective or transformative. Such limitations often occur when community partners are not included in the development of engagement projects. One way faculty members with more critical orientations towards service-learning and community engagement have addressed the tendency for such projects to only benefit students is to base civically engaged partnerships on social justice principles. In doing so, they consequently shift away from solely utilizing normative (ivory tower-centered) modes of engagement. Such critical orientations have emerged from much debate about who ultimately benefits from these kinds of partnerships, especially if the university fails to critically examine how such projects can sometimes reproduce inequities and negative stereotypes (Castañeda, 2008; Labonte, 2005; Parsons & Stephenson, 2005). Lacking critical frameworks or social justice approaches in university-centric community partnerships can end up hurting and exploiting communities, particularly those that are already experiencing marginalization. The neoliberal push towards revenue generation at many institutions of higher education also impacts such partnerships since universities now see communities as sources of revenue rather than as settings in which resources (human and otherwise) at the college can be utilized for transformative community and civic engagement in collaborative projects (Dowling, 2008). In fact, socially just community-university partnerships take as their center the need to make colleges accountable to the communities they work with as well as the development of connections that engender equitable reciprocity. Such partnerships are also consistently engaging in reflective practices that recognize the wealth of knowledge in communities and the importance of disrupting traditional notions of town-gown power relations as much as possible (Ash & Clayton, 2004).

Additionally, the practices of civic engagement through socially just community-university partnerships have the potential to create an environment in which students’ prejudices and stereotypes can be interrogated. Through this process, community partners become co-creators of knowledge while also gaining the benefit of student/faculty participation in projects. Civic engagement efforts that are linked to socially just community-university partnerships also have the benefit of demonstrating to students how community ← 5 | 6 → environments are spaces in which relevant and meaningful knowledge production is taking place. Thus, college students, including their professors, become learners and publically engaged scholars who have much to appreciate from community members (see Dostilio, 2017; Post et al., 2016). Concurrently, community members are able to share their stories and humanize the challenges and triumphs facing the groups in their organization. This is especially important for communities of color, who are often demonized and misrepresented in the mainstream media outlets. Students sometimes enter into community settings with inappropriate stereotypes and negative representations, yet by participating in civic engagement through socially just service-learning partnerships, uninformed notions about people and places can be disrupted and even transformed. Such transformation has the potential to develop a positive ripple effect in students’ future democratic (perhaps even radical) participation, especially if they engage with communities that challenge their normative understandings of race, class, gender, sexuality and citizenship.

By incorporating community-based and service-learning projects into college courses, students develop a range of civic engagement skill sets that are increasingly critical given the growing diversity in the United States. In fact, Astin, Vogelgesang, Ikeda, and Yee (2000) actually found not only positive outcomes across various measures such academic performance (critical thinking skills), values (commitment to activism), leadership (interpersonal skills), and plans to participate in service after college, but they also found that both students and professors “develop[ed] a heightened sense of civic responsibility and personal effectiveness through participation in service-learning courses” (pp. 3–4). In summary, the community partnerships included in courses, especially where reflection and discussion was a core of the pedagogical framework, mattered and made a difference for everyone involved. Bowman (2011) also found increased experiences with diversity when students participated in civic engagement projects and courses, which were not only curricular but also co-curricular and interpersonal. A reduction in racial bias was also detected in the study, and ultimately, Bowman (2011) noted, “the empathic bonds that occur primarily through interpersonal interaction—as opposed to simply ‘engaging’ with diversity abstractly through course work or workshops … lead to a greater importance placed on social action engagement and, ultimately, to civic action” (p. 23).

Additionally, Howard (1998, 2001) notes community-based and service-learning courses present the opportunity for students, professors and community actors to develop a synergistic and relational learning environment. Such an environment “encourages social responsibility; values and ← 6 | 7 → integrates both academic and experiential learning; accommodates both high and low levels of structure and direction; embraces the active, participatory student, and welcomes both subjective and objective ways of knowing” (Howard, 1998, p. 25). Such a synergistic experience is best attainable when best practices are applied to course structure and partnerships: (1) meaningful content, (2) voice and choice, (3) personal and public purpose, (4) assessment and feedback, and (5) resources and relationships (Melaville, Berg, & Blank, 2006). Ultimately, a well-planned civic engagement course has the potential to inspire students and community partners to appreciate reciprocity, lifelong learning, responsive engagement, and astute critical citizenship.

The inclusion of community engagement by the Carnegie Foundation furthered the efforts towards service-learning and civic engagement by developing a set of criteria and classifications that universities and colleges could aim towards (Carnegie Classifications of Institutions of Higher Learning, 2015). Such classifications have become badges of honor that communicate to the college community and its prospective students the value that a campus places on service-learning and civic engagement (Study Group on Civic Learning and Engagement, 2014). The growing emphasis of service-learning as community-based also reoriented the role of community members as central actors in community-university partnerships. In this capacity, community members could now work closely with faculty to develop the course structure, community projects, and assessment of not only student work, but also the overall partnership (Blouin & Perry, 2009; Ward & Wolf-Wendel, 2000). Service-learning has historically emphasized volunteerism and even charity approaches to community engagement, but the inclusion of critical, social justice frameworks has sharpened academic-community praxis by understanding how the intersections of race, gender, class and sexuality shape community and civic engagement (Mitchell & Humphries, 2007; Morton, 1995).

However, there remains a lack of diversity in terms of student and faculty participation in civic engagement and service-learning even while communities have become more diverse, in large because many institutions of higher education, especially research universities, do not reflect U.S. diversity. Although many academic fields are now incorporating community-based research and community service-learning, they still struggle to diversify participation, including those of community partners (Price, Lewis, & Lopez, 2014). There are many socio-political reasons why this is the case. In the context of students, college debt has made it difficult to participate in extracurricular activities that may take time away from supposedly real courses perceived as offering specific career skill sets (Bragg, 2001). We would argue that civic engagement and service-learning actually do prepare students for the ← 7 | 8 → workforce and democratic participation (Simons & Cleary, 2006). Also, more college students are working and attending school, which makes it difficult for students to participate in projects taking time away from their employment responsibilities. With regards to faculty, the growing pressure to publish peer-reviewed articles in the highest-ranking journals in the field, or produce books contracted with university presses, or secure large funds from public and private granting agencies, makes it more difficult develop civic engagement, community-based or service-learning opportunities for students and communities because of the time commitment they require (Abes, Jackson, & Jones, 2002; McKay & Rozee, 2004; O’Meara & Niehaus, 2009). However, as the chapters in this edited collection show, it is possible to combine research interests, student development, diverse socio-political strategies, and community engagement in ways that promote social justice, new knowledge formations, and collective academic spaces. The social justice partnerships discussed in this volume attempt to go beyond traditional notions of service-learning as merely volunteerism and charity work, and in fact demonstrate there is much to learn from partnerships with diverse Latina/x communities who are agents in their own historically and culturally specific realities.

The Emergence of a Latinx Community-Academic Praxis

This collection aims to transform the conversation about civic engagement and service-learning by showing the possibilities of social justice partnerships in action through a Latinx community-academic praxis. Such a framework takes as its guiding principle the idea that Latino communities engage in knowledge production and socio-political organizing on a daily basis, both within and outside of normative western modalities. The social justice orientation of this collection is not merely about pointing out or addressing injustices and misrepresentations, but also recognizing the cultural assets and funds of knowledge the community already embodies. Additionally, it is about acknowledging how these assets can potentially transform the ways in which civic engagement is practiced collaboratively over time. Lastly, this work is deeply influenced by the legacy of ethnic studies, especially Chicana/Latino studies and indigenous studies.

Scholar-activists have historically recognized the need to work with, and for, communities of color, particularly at times when mainstream academic spaces have pathologized communities of color (Collins, 2005; Kershaw, 2003; Torres, 2013). In many instances, these communities were not included in studies at all (Markus, Steele, & Steele, 2000). Ethnic studies scholars in the post-Civil Rights era aimed to turn such pathologizing on ← 8 | 9 → its head (Darder & Torres, 1998; Rosaldo, 1985). Many of these trailblazing scholar-activists also recognized the deep knowledge that was present in communities of color; communities that deserved to be recognized, included, and not dismissed. The critically important scholarship of Third World feminism furthered these efforts and broke down barriers by developing theoretical frameworks that took as its center the community—in all its complexity, contradictions, and possibilities (Sandoval, 1991). To be so closely engaged with communities was in many ways a political project given the emphasis on objective research in the academy as well as the historical racism and discrimination that was being felt across institutional, economic and political realms.

Despite the political and social progress since the Civil Rights era, the realities of changing demographics in the U.S. (and across the Americas) as well as the reemergence of white supremacy, is currently fueling a political sphere that demonize and scapegoat Latinx people, particularly those who are of Mexican-descent including undocumented, UndocuQueer and transgender identified people. In this political context, highlighting engaged scholarship that embodies a Latinx community-academic praxis is more important than ever as communities are under siege and attacked through discursive, symbolic and physical violence. Such violence damages self-esteem, reproduces economic inequities, and generates social responses that spur more audiovisual and interpersonal attacks (Chávez, 2013; Santa Ana, 2013). This collection demonstrates that rather than retreating to the Ivory Tower, we are witnessing increasingly more students and faculty (especially those of color and/or from working class backgrounds) engaging collaboratively with underrepresented communities in order to make visible these communities’ precious knowledge and speaking up against the hate speech that attempts to delegitimize and cower Latina/o communities. Professors, students and communities are working together to challenge the social structures that aim to restrict community access to resources, including educational opportunities, media spaces, and the built environment.

Furthermore, civic engagement and community service-learning often operate from the principle of difference, but what happens when communities share affinities with students and their professors? Very little scholarship is written about academics of color working on civic engagement and service-learning with communities of color. Although issues regarding class and educational privilege persist, many of the authors in this collection identify as first generation college students, Latinx and indigenous, and acknowledge the intersectionality of their lived experiences and community partnerships. Their engagement with Latina/o communities is not an exotic experience, but one of real material and personal connection. These connections are also ← 9 | 10 → politically informed, which builds on the long legacies of scholar-activists and the decolonization of knowledge. It is important to note that the authors in this collection are committed to the interstitial spaces of academia in order to foster engagement, empowerment and communication of what is often made silent.

Lastly, the authors demonstrate how to work collaboratively with communities so that the reciprocity of knowledge and its creation can formulate new ways of being and thinking in the world. The embodiment of a Latinx community-academic praxis is more than simply doing good in a community setting. The framework aims to disrupt negative stereotypes of Latinx communities and work within the fissures to dislodge the barriers to opportunities that are constantly placed between communities of color and institutions of higher education. We also do not believe you have to be Latinx to do the work presented here, but we do hope to inspire other scholars to use their educational resources in meaningfully productive ways that can potentially create a scholarship of social justice engagement produced collaboratively by communities, students, and faculty. Partnerships between communities and universities/colleges do not have to be exploitive, and the growing scholarship of engagement that challenges notions of race, ethnicity, class, gender and sexuality as it is practiced in community-based learning is one example of how critical academic spaces can promote social justice, equity, and peace, despite the current era of turmoil and hate speech (Kajner, Chovanec, Underwood, & Mian, 2013; Mitchell, Donahue, & Young-Law, 2012; Shabazz & Cooks, 2014). We are in a neoliberal moment where we need to find ways to escape the trap of individuals and develop new approaches for working through the community and university divide.

Making visible what is often invisible is a key theme that drives the chapters in this collection. The chapters’ orientations are influenced by Chandra Mohanty’s comments about the beauty and impetus of the written word:

Writing often becomes the context through which new political identities are forged. It becomes a space for struggle and contestation about reality itself. If the everyday world is not transparent and its relations of rule—its organizations and institutional frameworks—work to obscure and make invisible inherent hierarchies of power, it becomes imperative that we rethink, remember, and utilize our lived relations as a basis of knowledge. Writing (discursive production) is one site for the production of this knowledge and this consciousness. (2003, p. 78)

In addition to writing about civic engagement, service-learning courses, and community-based research projects, many authors also include the lived experience of social relations as a methodological and theoretical writing tool (Delgado Bernal, Burciaga, & Flores Carmona, 2012; Huber, 2009). This ← 10 | 11 → scholarly practice, in some cases embodied as testimonio, is a political effort to insert the voices of Latinx scholar-activists in the discussion of civic engagement and community service-learning. These voices are often absent in the civic engagement scholarship, and in many cases at the major academic conferences as well, thus this edited monograph brings Latina/o scholar-activist voices to the forefront of such conversations. The chapters in the book are organized under three themes: (1) rethinking community and civic engagement; (2) community voices and the politics of place; and (3) expanding the media and cultural power of communities.

The first thematic section of the book—“Rethinking Community and Civic Engagement”—addresses the ways in which faculty, students and community partners are rethinking the ideas and practices of community and civic engagement. The first chapter by Antonieta Mercado titled, “Civic Engagement: Learning from Teaching Community Praxis,” addresses the incorporation of tequio, which means community work in Náhuatl language, within community based courses as a process for building bonds and trust with immigrant and indigenous communities. Next is a chapter by Joseph Krupczynski titled, “Imagining a Nueva Casita: Puerto Rican Subjectivities and the Space of the ‘In-between’ on an Urban Farm in Western Massachusetts,” and he describes a project that helped develop a more complex understanding of cultural heritage in an effort to create a transnational and emancipatory space/place firmly rooted in Latina/o cultural subjectivities. Claudia A. Evans-Zepeda’s chapter, “Subject-Heading or Social Justice Solidarity? Civic Engagement Practices of Latinx Undocumented Immigrant Students,” offers reflections on the ways in which undocumented Latina/o college students participate in critical civic praxis to subvert the racist nativism prevalent in the dominant immigration discourse. The following chapter, “Keeping It Real: Bridging U.S. Latino/a Literature and Community Through Student Engagement,” by Marisel Moreno demonstrates how applying community based learning pedagogy to the study of U.S. Latino/a literature provides unique opportunities for students to develop practices and dispositions that help to enhance their understanding of civic engagement and social justice. Lastly, the co-authored chapter by Clara Román-Odio, Patricia Mota, and Amelia Dunnell titled, “Public Humanities and Community-Engaged Learning: Building Strategies for Undergraduate Research and Civic Engagement,” offers a case study to show how by linking the public humanities to community-engaged learning we can build meaningful strategies to strengthen both undergraduate research and civic engagement.

The second thematic section of the book—Community Voices and the Politics of Place—discusses the importance of community voices in shaping ← 11 | 12 → the reclamation and contestation of place and belonging. The section begins with Jonathan Rosa’s chapter, “Community as a Campus: From ‘Problems’ to Possibilities in Latinx Communities,” in which he points to the productive possibilities that emerge when we shift from viewing marginalized communities as static objects of academic analysis to dynamic sites of collaborative knowledge production. Following is the chapter titled, “Motherists’ Pedagogies of Cultural Citizenship: Claiming Rights and Space in a Xenophobic Era,” by Judith Flores Carmona and here she describes how Latina mothers enact pedagogies of the home and their responsibility to fight for basic social needs and the various forms of activism that take place through their participation in their children’s education and educación in their community, school, and homes. The chapter by J. Estrella Torrez titled, “Responsibility, Reciprocity, and Respect: Storytelling as a Means of University-Community Engagement,” presents three tenets—responsibility, reciprocity, and respect—extrapolated through work with Latino and Indigenous communities that can be used in developing collaborative relationships in predominantly white U.S. regions. The following chapter, “Arizona-Sonora 360: Examining and Teaching Contested Moral Geographies along the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands,” by Celeste González de Bustamante suggests that when coupled with a critical borderlands pedagogy, the concepts of moral geography and counter-cartographies can be useful tools for understanding the dynamics of the Arizona-Sonora borderlands. Lastly, Ginetta E. B. Candelario’s chapter, titled “Saber es Poder: Teaching and Learning about Social Inequality in a New England Latin@ Community,” discusses the local Latino/a community of Holyoke, MA as a case study of Puerto Rican experience in the U.S. and the importance of Latino Studies’ founding principle of community service and engagement for understanding the socio-politics of place.

The final thematic section—Expanding the Media and Cultural Power of Communities—shows the multiplicity of cultural production can work as valuable pathways for civic engagement and telling stories that prioritize community lives and knowledge production. The first chapter by Jillian M. Báez titled, “Media Literacy as Civic Engagement,” calls attention to how media literacy, as a form of civic engagement, not only involves learning how to deconstruct media texts, but also understanding oneself as a player within the media system who can advocate and/or contest media production, ownership, and content. Following is the chapter, “‘I Exist Because You Exist:’ Teaching History and Supporting Student Engagement via Bilingual Community Journalism,” by Katynka Z. Martínez in which she describes how student demands for a more relevant education and a more just society led to the emergence of a Latina/o newspaper that is still advocating for ← 12 | 13 → community rights, especially in the current era of gentrification in San Francisco. The third chapter, titled “Hashtag Jóvenes Latinos: Teaching Civic Advocacy Journalism in Glocal Contexts” by Jessica Retis describes the powerful impact that is produced when students include their personal experiences when creating stories by, with, and for young Latinos. Similarly, Sonya M. Alemán, in her chapter titled, “Chicana/o Media Pedagogies: How Activism and Engagement Transform Student of Color Journalists,” chronicles the types of civic engagement and/or activism that was catalyzed as the result of a community-media partnership and the differentiation between activism and engagement this partnership had for students who belonged to racially and ethnically marginalized groups. The final chapter of this anthology is by Rogelio Miñana, and in “Lessons from Migrant Youth: Digital Storytelling and the Engaged Humanities in Springfield, MA,” he examines the positive potential of digital storytelling as a space for self-expression for young migrants and the lessons that faculty and students learned from community members on the role of higher education in society as well as on the pedagogy and methodologies of the engaged humanities.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 302

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433148255

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433150081

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433150098

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433150142

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433147265

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11957

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (January)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XII, 302 pp., 1 b/w ill.