A Black Woman's Journey from Cotton Picking to College Professor

Lessons about Race, Class, and Gender in America

Summary

As a daughter, sister, wife, mother, and scholar-activist, Mildred lived her core beliefs: she felt that it was important to validate individual human dignity; she recognized the power of determination and discipline as keys to success; and she had a commitment to empowering and serving others for the greater good of society. Such values not only characterized the life that she led, they are exemplified by the legacy she left. A Black Woman's Journey from Cotton Picking to College Professor reflects those core values. It celebrates ordinary lives and individuals; it demonstrates the value of hard work; and it illustrates the motto of the National Association of Colored Women, “lifting as we climb.”

A Black Woman's Journey from Cotton Picking to College Professor can be used for courses in history, ethnic studies, African-American studies, English, literature, sociology, social work, and women’s studies. It will be of interest to sociologists, anthropologists, historians, political economists, philosophers, social justice advocates, humanists, humanitarians, faith-based activists, and philanthropists.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Advance praise for A Black Woman’s Journey from Cotton Picking to College Professor

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword by James D. Anderson

- Acknowledgments

- Part I: Sunrise

- Chapter One: Introduction by Stephanie Shaw and Menah Pratt-Clarke

- Historical Context

- Personal Context

- Overview

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Two: The Critical Black Feminist Autobiography

- Black Women’s Autobiography

- Critical Black Feminism

- Autobiographer’s Introduction

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Three: Starting After Slavery

- The Thirkill Family

- The Sirls Family

- Early Years

- White People

- Key Lessons

- Photos

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Four: Surviving the Great Depression

- Daily Life

- Church and Religion

- Struggling to Survive

- Key Lessons

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Five: Segregated and Sharecropping

- The Black White’s Houses

- Cotton Pickin’, Corn Shuckin’, and Cow Milkin’

- Health and Medicine

- Black Housing

- Key Lessons

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Six: Black Girlhood

- The Secret

- A Sister’s Death

- “Mama’s Little Black Girl”

- High School

- Kansas City

- Key Lessons

- Photos

- Notes

- References

- Part II: Sunshine

- Chapter Seven: A New Beginning

- Jarvis Christian College

- Butler University

- Jamaica

- University of Indiana

- Los Angeles

- Detroit

- Key Lessons

- Photos

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Eight: Pittsburgh and the PhD

- Marriage

- Children

- The Doctoral Program

- Community Engagement

- Assassination and Activism

- Key Lessons

- Photos

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Nine: Normal University Racism

- Normal, Illinois

- Ted’s Faculty Journey

- Mildred’s Faculty Journey

- Motherhood

- Key Lessons

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Ten: Black History Project

- The Vision

- Empowerment

- The Stories

- The Impact

- Key Lessons

- Notes

- References

- Part III: Sunset

- Chapter Eleven: A Legacy

- “We Shall Overcome”

- Retirement

- Recognition

- Key Lessons

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Twelve: Travel, Trials, and Triumph

- The White House

- Trials

- Memories and Memorial

- Music Lessons

- Amazing Grace

- The Concert

- Photos

- Notes

- References

- Appendix A: Theodore Pratt’s Curriculum Vitae

- Appendix B: Mildred Pratt’s Curriculum Vitae

- Index

- Series Index

| Figure 3.1: | George, Rosa, and Eula Thirkill, circa 1901 |

| Figure 3.2: | Eula Thirkill, age 16, circa 1914 |

| Figure 3.3: | Etherline Sirls, circa 1938 |

| Figure 6.1: | Ruby Sirls (deceased), age 6, 1944 |

| Figure 6.2: | From left, Mozelle, Eula, Era, RP, and Bernice Sirls, 1944 |

| Figure 6.3: | George Sirls, age 21, 1943 |

| Figure 6.4: | Irmagene Sirls, circa 1940s |

| Figure 6.5: | Era Sirls, circa 1940s |

| Figure 6.6: | Mildred Sirls, age 16, 1944 |

| Figure 6.7: | Mildred Sirls, Shiloh High School, 1946 |

| Figure 6.8: | Ms. Ira Henry, Shiloh High School, circa 1940s |

| Figure 6.9: | Mildred Sirls, Shiloh High School Graduation, 1946 |

| Figure 7.1: | Mildred Sirls, Jamaica, 1952 |

| Figure 7.2: | Eula Sirls, funeral program, 1975 |

| Figure 7.3: | Mildred Sirls, Los Angeles, circa 1950s |

| Figure 8.1: | Ted and Mildred Pratt, Pittsburgh, 1964 |

| Figure 8.2: | Mildred Pratt, University of Pittsburgh graduation, 1969 |

| Figure 12.1: | White House dinner menu, June 10, 1994 |

| Figure 12.2: | Mildred’s message to the universe, 2012 |

| Figure 12.3: | Mildred Pratt, journals and writings, 2017 ← xiii | xiv → |

Note: James D. Anderson is the Dean and Edward William and Jane Marr Gutsgell Professor of Education at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. His scholarship focuses broadly on the history of U.S. education, with specializations in the history of African-American education in the South, the history of higher education desegregation, the history of public school desegregation, and the history of African-American school achievement in the twentieth century.

At first glance, Dr. Mildred Sirls Pratt’s story is one of the genesis, rise, and remarkable triumph of an extraordinary individual overcoming herculean odds. To be sure, noteworthy achievement is a central part of her story. Yet, the more we read about the things that tormented her, of the inner strengths she mustered to break down countless race, gender, and class barriers, and of her intellect and determination to carve out a better life for herself and her family, we realize that her experiences are reflective of the larger world made and remade by generations of ordinary Black men and women. However, her remarkable feats—despite successive setbacks—as she navigated a career as a tenure track professor without a blueprint is a story of legend. Learning of Mildred Sirls Pratt’s experiences connects us with the life and culture of the generations of African-Americans who lived from the end of slavery through the postmodern Civil Rights movement. Her childhood experiences in the Jim Crow South connects us to the subterranean culture of African-Americans in various ways, from games and songs, to the language, food, clothing, medical remedies, religion, education, and labor of tenant farmers and ← xv | xvi → sharecroppers. Her professional experiences as a graduate student, social worker, and professor in northern states reflect the persistent forms of racism inflicted on African-Americans irrespective of education, income, and class. Finally, her accomplishments reveal how individual Black women succeeded in spite of race and gender discrimination.

Her life as a sharecropper in East Texas represents a common experience for Blacks in southern states. At the turn of the twentieth century, approximately half of all Texas farmers were tenants and the highest proportion were African-American—69 percent compared to 47 percent for Whites (Harper & Odom, 2010). In Texas, as in other southern states, a hierarchy of tenant farmers developed, according to what resources tenant farmers could bring to the negotiation. At the top were share and cash tenants who could furnish their own mules, plows, seed, feed, and related necessities. At the bottom were sharecroppers who could only supply their labor. The Sirls family, like most African-American tenant farmers, was at the bottom. The Sirls were part of the East Texas cotton economy where approximately three-quarters of the state’s cotton acreage lay prior to the end of World War II.

Mildred Sirls Pratt’s memoir informs us of the African-American traditions and also of the economic and political conditions under which Black tenant farmers lived and worked in the pre-Brown v. Board of Education era. In short, her life channels us into the stream of African-American life and culture as it was being created in the farm tenancy world of the twentieth century. Sharecropping, above all else, meant poverty, hunger, and political exploitation. Still, African-American cultural forms emerged in the midst of a plantation-like society that systematically repressed and starved sharecroppers.

Every Sunday, her family walked miles to church where she learned to “line out” the music as the congregation followed. This practice was especially crucial in a community where there were few or no songbooks and people in general could not read. They sang such gospel songs as “Down by the Riverside” (also known as “Ain’t Gonna Study War No More”). For recreation, they jumped rope and played croquet and other games like “Little Sally Walker.” These games were played by generations of African-American children across the southern states and moved north and west with the Great Migrations. Such games, folktales, religious rituals, poems, and songs formed the foundation of African-American ethical values and shaped their views of a just and humane society. In his anti-Vietnam war speeches, Martin Luther King would draw upon words from “Down by the Riverside,” calling for all people of goodwill to come to a massive act of conscience and say in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “we ain’t goin’ to study war no more.” Such songs and rituals connected African-Americans collectively and individually.

More importantly, Mildred Sirls found within her culture the values and beliefs that propelled her to transform a childhood of poverty and exploitation into a remarkable career as a social worker and professor. Critical to her transformation ← xvi | xvii → was the long-standing tradition that poor African-American families placed on the value of education. In Mildred’s words, “frostbitten feet were the norm. In spite of the situation we did not miss a day in school unless we were ill.” Before going to bed at night she and her siblings would gather in their mother’s room and listen to the reading from the Bible and a book of poems. The poems she learned to recite (“House by the Side of the Road” by Sam Walter Foss; “Invictus” by William Ernest Henley; and “The Creation” by James Weldon Johnson) were learned by African-American schoolchildren across the South. There is hardly a member of her generation that could get through school without learning to recite and interpret such poems and verses that remained the gold standard in southern Black education, at least until the end of racially segregated schooling in the post-Civil Rights era.

Mildred Sirls found that the value of education emphasized at home was also deeply affirmed in school. She recalls the great fortune of having excellent teachers who believed in children learning, asserting that “the Black teachers were relentless to teach.” One teacher, Ira Henry, took great interest in Mildred and encouraged her to excel at the highest level. Mildred Sirls graduated Valedictorian of her high school in 1946, and with Ms. Henry’s guidance she was admitted to Jarvis Christian College in Hawkins, Texas, a historically Black college. In the post-World War II era, historically Black colleges and universities enrolled more than 90 percent of Black college students, making her college experience reflective of the emerging postwar Black middle class (Harper, 2007). She excelled at Jarvis Christian and followed her undergraduate experience with work and graduate study. Following her graduation from Jarvis Christian College, she went on to earn three advanced degrees: a Master’s degree in religion from Butler University, a Masters of Social Work degree from Indiana University, and a PhD in Social Work from the University of Pittsburgh.

Mildred Sirls’ experiences in the north showed that intransigent racism and persistent discrimination were not peculiar to the South. Each milestone along the way taught profound lessons about the difference between Jim Crow segregation in the South and the day-to-day racism and discrimination that characterized close encounters with Whites in northern communities. As a child, she lived in segregated and insulated “Black enclaves” where the Whites she saw were usually the ones her mother worked for as a maid. Graduate school and professional life brought her into close encounters with different and more subtle forms of racism and discrimination in northern and Midwestern states—Indiana, Missouri, Michigan, and Pennsylvania.

Ultimately she was admitted to the doctoral program in Social Work at the University of Pittsburgh where she was the only Black student in the advanced degree program. While in Pittsburgh she would meet her future husband Theodore Pratt, a nuclear physicist graduate student at Carnegie Institute of Technology (now Carnegie Mellon University). They were married in 1964 and following ← xvii | xviii → the birth of their two children, Awadagin and Menah, issues of race discrimination took on a new and more ominous meaning.

Routine forms of discrimination became serious problems for the family. Racism was particularly painful when inflicted on their defenseless children in school and out of school. Mildred Pratt learned quickly that having three advanced degrees and a professional occupation did not shield her from the kinds of racism faced by ordinary Black men and women. Following the completion of her PhD, she and her husband took faculty positions at Illinois State University. While taking a walk in her residential community in Normal, Illinois, a White neighbor offered Dr. Pratt a job as a cook and a maid, reminding her that Black bodies were always presumed to be an available pool of cheap, uneducated, menial labor. Inside the academy was no less painful. Mildred Pratt describes her worst experience as the discrimination she faced when trying to get promoted.

Hence, it is not surprising that Dr. Mildred Sirls Pratt focused a significant part of her professional career on creating and sustaining the Bloomington-Normal Black History Project, which gathered the life stories of almost 100 elderly African-Americans. So much about her life had taught her the crucial lesson of knowing from whence you came and of transmitting from generation to generation African-American forms of resistance and the ways in which they affirmed their humanity through culture, music, and religion.

Her life is an amazing journey from sharecropping to the academy and the ways in which she traveled the stony road makes her life an all and sundry reflection of the African-American experience. Her self-respect, intellect, and self-determination led her to accomplish great things in life. She was an excellent scholar and teacher, traveled the world (Brazil, England, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Sierra Leone, Jamaica, Bahamas, France, Poland, and Italy), met Presidents Clinton and Obama, watched her son give a piano recital in the White House, and saw her daughter become an Associate Chancellor at the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. Her memoir is an insightful window into what it means to be Black in America, individually and collectively.

References

Harper, B. (2007). African American access to higher education: The evolving role of historically black colleges and universities. American Academic, 3, 109–128.

Harper, Jr., C., & Odom, E. D. (2010, June 12). Farm Tenancy. Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved from http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/aefmu

This book would not have been possible but for the interest and commitment of Professor Rochelle Brock, editor of Black Studies and Critical Thinking Series with Peter Lang, to support the scholarship of African-Americans. Thank you, Rochelle, for your unwavering commitment and belief in me.

This book is the culmination of a five-year journey that began when my mother died on August 6, 2012. Writing her story enabled us to stay connected as I daily touched her handwritten notes and sought to feel and decipher her joy, pain, sorry, loss, passion, and wisdom. She walked alongside me as I wrote her story. Others accompanied us as well. The ancestors seemed to have orchestrated the universe in such a way as to ensure that this project would move toward fruition. At crucial moments, unexpected angels were sent my way to provide encouragement and assistance.

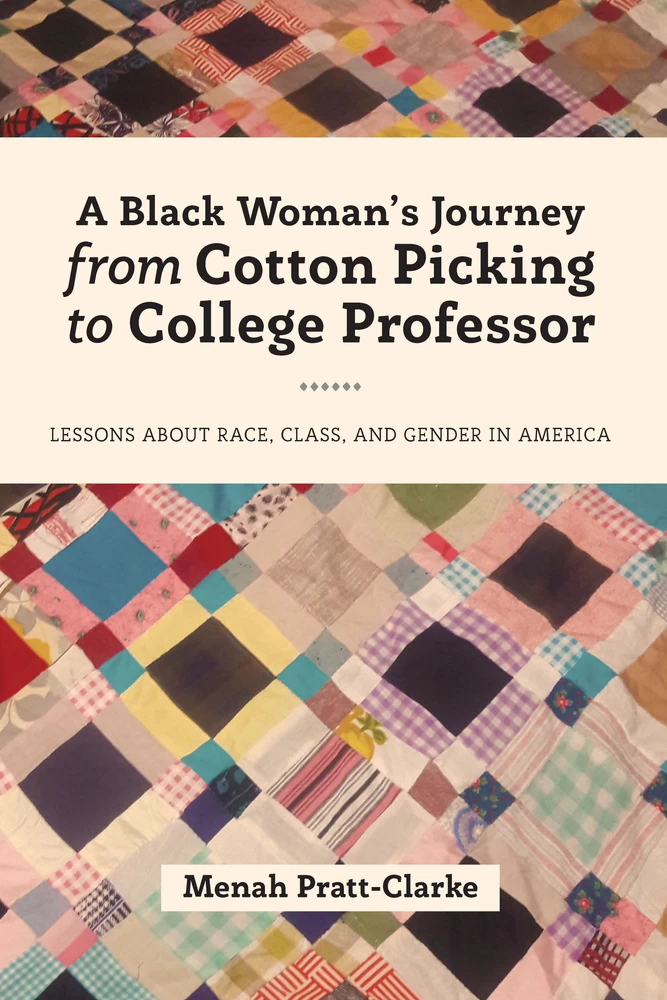

Shortly after my mother’s death, Patty Sirls, my uncle’s wife, sent my grandmother’s quilt (book cover photo) and a crocheted bedspread to me in the spring of 2013. Just having the material possessions of my own ancestors near provided an ongoing reminder of our shared struggle. A few months later, during the summer of 2013, our family stopped at the Lawrence County, Alabama Archives on the way to the Thirkill Reunion (my mother’s grandfather’s family). Not only were the employees helpful, but Ms. Lisa Lentz, another visitor to the Archives who was researching her own family history, was a fabulous gift. She graciously took time ← xix | xx → away from her own research to look through documents and educate me on how to do genealogy and how to piece together little lines of data to understand a life. Being on the ancestral land of my great-grandparents in Alabama reminded me of the connection between my mother’s story and their stories. Coming full circle, in November 2013, I visited the gravesite of my mother’s grandfather, George Thirkill in Phoenix, Arizona. Patty and I placed flowers on his headstone.

In 2016, the writing and work had ground to a halt for this manuscript. Other book projects garnered my attention: Journeys of Social Justice: Women of Color Presidents in the Academy (Peter Lang, 2017) and Reflections about Race, Gender, and Culture in Cuba (Peter Lang, 2017). My friend, Alfreda Burnett, courageously suggested I contact Olivia Butler, an amazing scholar, historian, and writer, for a jump-start on the manuscript. Metaphorically, Olivia was the jump cable that I needed to restart the work. She provided invaluable suggestions and ideas that significantly strengthened the manuscript. I am very grateful to both Alfreda and Olivia.

I am thankful for family friends, including Darlene Miller, Marc Miller, Pam Muirhead, and Patsy Bowles, who were my mother’s best friends. They were an invaluable source of inspiration and encouragement. My mother’s colleague and friend, Professor Stephanie Shaw, worked with her at Illinois State University. She graciously offered to write the introduction. She believed in this work from the beginning. I am grateful for her. Professor Darlene Clark Hine, who also knew my mother, was so supportive of this project. Thank you, Stephanie and Darlene.

Details

- Pages

- XXVI, 272

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433149702

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433149719

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433149726

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433149740

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433149733

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11827

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13287

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (January)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XXVI, 272 pp., 20 b/w ill.