Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance Praise for Rhetoric at the University of Chicago

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Rhetoric at the University of Chicago: A Materialist History

- Introduction: The Windy University

- The Materialist Turn and the Organization of This Book

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 1. Richard McKeon and “Rhetoric in the Middle Ages”

- McKeon’s Early Chicago History

- Network of McKeon’s Aristotelianism

- McKeon, Randall, and Neo-Aristotelian Criticism

- A Demonstration of Critical Attitude: McKeon and Burke

- McKeon’s “Rhetoric in the Middle Ages”

- Chicago Reactions to “Rhetoric in the Middle Ages”

- McKeon’s Class “The Greek Rhetoricians”

- Burke’s Response in Rhetoric of Motives

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 2. Kenneth Burke and “The Problem of the Intrinsic”

- The Rise of Intrinsic Criticism at Chicago

- Burke’s Courses as Chicago History

- Burke’s Revisions to Neo-Aristotelianism

- Burkean Revisions to Neo-Aristotelianism

- The Neo-Aristotelians Break Ranks: Norman Maclean, the Intrinsic, and Authority

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 3. Demetrius and Kenneth Burke’s “Rhetorics”

- The University of Chicago, Institutional Context, and Department Politics

- R. S. Crane and Criticism of Demetrius

- Richard McKeon and Demetrius’s “Forcible” Style

- Deinotes, Identification, Dramatism, and Omission

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 4. Richard Weaver and “To Write the Truth”

- Weaver, the “Argument From Circumstance,” and Writing at the University of Chicago

- Curricular Revisions, Committee Politics, and Weaver’s “To Write the Truth”

- Sharon Crowley, Politics, and Rhetorical Theory

- Weaver, Henry W. Sams, and the Professionalization of Rhetoric

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 5. Manuel Bilsky, Richard Weaver, Robert Streeter, and McCrea Hazlitt and “Looking for an Argument”

- Neo-Aristotelianism at the University of Chicago

- Logic and Rhetoric in the Writing Program

- Reaction to Henry Sams, Ward, and Burke: “Looking for an Argument”

- “Looking for an Argument” and the Boundaries of Disciplinary Scholarship

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Chapter 6. Wayne Booth and “The Revival of Rhetoric”

- Booth and Chicago’s Philosophical and Dramatistic Rhetoric

- Negative Reviews of Rhetoric of Fiction

- Booth’s “The Revival of Rhetoric”

- Reactions to “Revival of Rhetoric”

- Apologists for the Rhetoric of Fiction

- Booth and Burke’s “Tears”

- Booth’s “Way of Knowing” and Critical Inquiry

- Notes

- Bibliography

- “Utterly Mad”: Chicago, Conclusions, and Rhetorical Catastrophes

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

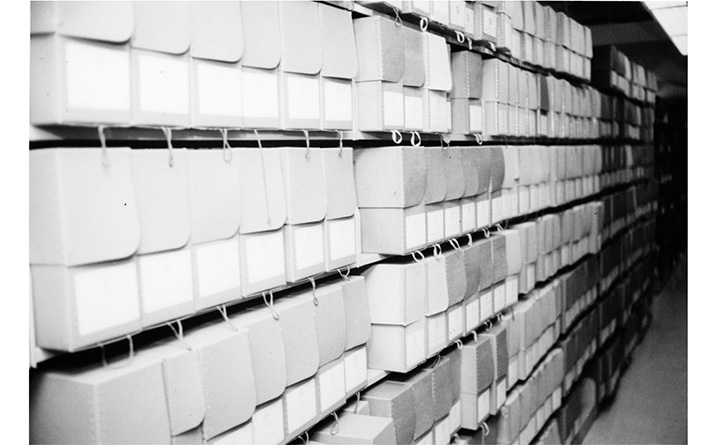

0.1 Joseph Regenstein Library, Special Collections 2

1.1 Richard McKeon, Informal 2

2.1 R. S. Crane, Caricature 1

3.1 F. C. Ward, Photo 1

4.1 Richard Weaver, Formal 1

5.1 Henry Sams, Formal 1

6.1 Wayne Booth, Group 2

7.1 Wilma Ebbitt, Group 5

While this book is very much about the University of Chicago from the 1930s through the 1960s, it is also very much about the city of Chicago, as well. I was born in Chicago in 1970, but grew up in Chicago’s shadow, the part of Northwest Indiana known as “The Region.” This area was and still is greatly affected by its looming neighbor. All of its news stations are Chicago-broadcasted, and it is the only of portion of Indiana in the Central Time Zone. What I mean to say by this is that no matter where I have gone or lived, I’ve still existed within the gravitational force of this city, and in that sense I have something in common with many of the characters in this history. I’d first like to thank my parents, George and Lureen Beasley, for their own proximity to the Chicago area and its resulting cultivation of my intellectual and cultural growth. I am indebted to my professors at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, for their dedication to the study of archives and their importance in our histories: David Blakesley, Shirley Rose, Thomas Rickert, and especially to my dear mentor, Patricia Sullivan. I’d also like to thank those involved with the Kenneth Burke Society and the Rhetoric Society of America who at some point have read portions of this work or have given feedback at conferences: Jack Selzer, Ann George, Elizabeth Weiser, Robert Wess, and Richard Enos.

This book would not be possible without the assistance of Barbara Gilbert, Assistant Archivist of the Special Collections Research Center ← ix | x → at the University of Chicago Library. I’ve gotten to know Barbara over the last fifteen years, and I still see her every time I return to the Chicago area. Barbara is a gifted archivist, who loves her work and sharing it with others. Again, this book would not be possible without her dedication to the Special Collections Research Center and to the scholarship which she facilitates. I am extremely grateful for her generosity and indebted to her service. I am also extremely grateful to Megan Simpson at Peter Lang Publishing, who has guided me throughout the manuscript process and especially to Luke McCord, whose editorial assistance has been invaluable.

I would like to thank my colleagues at Valparaiso University, DePaul University, and the University of North Florida for their encouragement and assistance in the development of these ideas and in the production of this book, especially the memory of Arvid “Gus” Sponberg, a student of Norman Maclean’s at Chicago, a member of Janice Lauer Rice’s first rhetorical seminars in Michigan, and a dear colleague at Valparaiso University.

I would like to express my gratitude to Kimberly, who in the middle of our teaching careers, decided to move us to downtown Chicago, so that I could be closer to my research. Living and working in the city, waiting for and riding the Martin Luther King Drive bus or the Red Line up and down the spine of the city was simultaneously one of the most spontaneous and yet grounding experiences of our young lives, and without that decision this book would never have been written. I am grateful to share her inspiration, patience, and dedication to this particular Chicago story, as we have benefited from those that have shared these histories with us.

Finally, I dedicate this book to all Chicagoans, far and wide, who live in the shadow of its history, those who have not enjoyed safe neighborhoods, economic independence, or social justice. May we endeavor to lean on each other’s shoulders, no matter how big or small they are.

St. Johns, Florida

RHETORIC AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

Figure 0.1: Joseph Regenstein Library, Special Collections 2.1 ← 1 | 2 →

Introduction: The Windy University

“To write now is to archive.”2 I recently heard this from a panel presenter at a major conference in rhetoric and composition. While she was specifically speaking about the advancements in rhetorical strategies involving the canon of memory, I did feel the weight of these words in a much broader sense in the research and writing for this book. I first stepped into the Regenstein Library on the campus of the University of Chicago to begin this research back in 2001. At the time, I would have never considered myself an archivist, or that what I would be doing would be considered archiving. Now, however, fifteen years later, I am acutely aware of how much writing truly is archiving. This raises many more questions than answers, however; and there are questions that I would like to place here at the beginning to inform the readers as they begin this archival journey through the history of rhetoric at the University of Chicago.

I’ll admit that the first phase of my initial research would be considered “recovery.” I had read Berlin’s statement in Rhetoric and Reality about how “one of the earliest articles to attempt to reintroduce the concept of classical conception of rhetoric to the writing class came from a group of teachers at the University of Chicago,”3 but other than that I had neither read much of Booth or Weaver, McKeon or Crane, and never even heard of Wilma Ebbitt, Henry Sams, F. C. Ward, Albert Duhamel, Paul Aldus, or at that point, James Sledd. Getting a “lay of the land” so to speak, took a few years, recognizing the critical stances of the participants, hearing their sneers in faculty meeting minutes, feeling their solidarity when confiding with a colleague in a letter. During the time that I had begun this research to the time I began writing it out, composition studies underwent what is called an “archival turn,” meaning that historical recovery of these materials was problematic. According to David Gold:

Moving beyond recovery also means that we can also no longer afford simple narratives of heroes and villains. It is not enough to simply point to the past for evidence of practices that align with our own construction of what is progressive, what is reductive; rather, we must examine how historical actors responded to their own contemporary exigencies, both micro and macro.4

It took years to map out who the players at Chicago even were, and my 2007 article in College Composition and Communication, “Extraordinary Understandings’: F. C. Ward, Henry Sams, and Kenneth Burke at the University of ← 2 | 3 → Chicago” was exactly that. For me at that time, this research demonstrated that Ward, Sams and Burke were the progressive heroes and that Crane, McKeon, and Weaver were the reductive villains. So this would be one of the first turns that this research would take. After realizing that no matter how much I wanted Burke to be the hero and Crane or Weaver the villains, it does not matter whether they were in the first place, since they were motivated by other exigencies, especially within the institutional vagaries of the University of Chicago. What that article did, however, was to expose how these contingencies could be traced through other participants and documents. I first began with Richard Weaver, how many of his pronouncements in committee meetings did not match the Platonic descriptions of him from the histories of rhetoric and composition. For me, this demonstrates the first characteristic of the archival turn that I believe these chapters demonstrate. In Rhetoric and Composition as Intellectual Work, Susan Miller wrote, “Writing studies leads archivists to look for evidence of writing practices, of pedagogy, and of individual modes of composing for the sake of identifying the plausible cultural work a text may have accomplished.”5 What did became evident in a revision of Weaver’s rhetorical theory was that his texts and their creation had important cultural ramifications for rhetorical history itself. This article took many years to develop, but it was eventually published in Rhetoric Review as “Ideas and Consequences: Richard Weaver, Sharon Crowley, and Rhetorical Politics” and is excerpted here as the fourth chapter on Weaver’s “To Write the Truth.”

The second characteristic of the archival turn that is represented in this work is the re-utilization of already existing recovery research. Lynee Lewis Gaillet wrote that “Researchers using primary texts [are able to] add to existing archives in ways that make knowledge rather than simply finding what is already known.”6 This is a very specific application of the condition of “to write now is to archive.” For example, in the chapter I just mentioned, Weaver’s “To Write the Truth,” I utilized Sharon Crowley’s 2001 essay, “The Case of the Man from Weaverville” to turn back into the history of the University of Chicago. So, rather than “simply finding what is already known,” I was able to “make knowledge.” In Burke’s words, I can “turn the matter around,” and rather than using the archives to help us understand the theories of a particular rhetorical theorist, we can use theorists and their works to help us understand what those micro and macro contemporary contingencies actually were. This type of “turning the matter around” utilizes the important recovery research in Jack Selzer and Ann George’s Burke in the 1930s, Elizabeth Weisser’s “As Usual I Fell on the Bias,” and Robert Wess’s “Burke’s McKeon ← 3 | 4 → Side: Burke’s Pentad and McKeon’s Quartet” in the first and second chapters. In the fourth chapter it is Sharon Crowley’s “When Ideology Motivates Theory: The Case of the Man from Weaverville” that receives this treatment, as well as John Ross Baker’s 1973 article, “From Imitation to Rhetoric: the Chicago Critics, Wayne Booth, and Tom Jones” in the final chapter on Wayne Booth’s “Revival of Rhetoric.”

A third characteristic of the archival turn that this study is guided by is an attenuation to the availability of materials in the University of Chicago archive. If Galliet is correct, that “archives shape identity,”7 then it is obvious how the University of Chicago archive itself defines rhetoric. McKeon’s archive is large, front, and center, while the chair of the English College, Henry Sams, is reduced to a single subject folder. John Brereton and Cynthia Gannett argued for the inclusion of “the narratives of archival construction itself,”8 and by this measure the archives themselves are saying out loud: Richard McKeon was rhetoric at Chicago. While the University of Chicago archives hold the papers of Wayne Booth, his papers are not even processed. Booth wrote more about rhetoric than anyone who ever taught at the University of Chicago, but even the contents of Booth’s desk are just sitting in boxes.

The fourth characteristic of the archival turn that is represented in this work is the foregrounding of my own personal attachments and commitments to my findings. Lynee Galliet wrote, “Archival researchers must immerse themselves in study of the place, time, and culture they are researching.”9 It is not hard at all to participate in the celebrated atmosphere of the University of Chicago. While many of the haunts of Richard McKeon, R. S. Crane, Richard Weaver, Kenneth Burke, F. C. Ward, Henry Sams and thousands of the students who attended the University of Chicago from 1947 to 1959 are gone, I took in as much of the atmosphere as I could: 57th Street Books, the University Co-Op Bookstore, the Medici Café, or wandering the halls of the Oriental Institute. I even moved to Chicago in order to be closer to my research—I can always commute to work, but having to travel to do research might prevent me from getting good work done. While in Chicago, I mainly commuted by public transportation, noting how the Cottage Grove #4 bus route was unfazed by those nostalgic landmarks, choosing instead to skirt the western edge of campus on the way to the university emergency room. During several of these trips, my bus drivers stopped many times to wait for the police to usher off non-paying customers, while the throng of angry rush hour commuters screamed to no avail. Didn’t these people realize that we were passing the spot where the nuclear age was born, where the economic systems of the ← 4 | 5 → world were changed, or even in my case, where a return to rhetoric in American English departments was made possible? No, they did not, and this seems to be one of the points of this particular time period—as much as some at the University of Chicago tried to elevate argument about only the most noble subjects, there were those who believed that there were arguments west of Ellis Avenue, which marks the western boundary of the campus, that mattered just as much. This to me is one of the most rewarding results of this project. Galliet wrote the following:

By pointedly discussing the reasons they select particular research projects, their personal relationships to the materials at hand, and their prejudices and assumptions, archival researchers writer truer narratives—bringing a rich perspective to subjects under investigation while in many cases discovering topics new to rhetorical studies, unexamined collections, and novel venues for rhetorical agency.10

Details

- Pages

- XII, 194

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433150906

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433150913

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433150920

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433150890

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13693

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (September)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XII, 194 pp., 8 b/w ill.