Imprinting Identities

Illustrated Latin-Language Histories of St. Stephen’s Kingdom (1488–1700)

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Foreword

- 1. Introduction

- 1.1. Concepts and Research Problems

- 1.2. Scope and Structure of the Thesis

- 1.3. Sources

- 2. Historical Imagery

- 2.1. Dominant Narratives in Chronological Overview

- 2.1.1. At the Court of Matthias Corvinus

- 2.1.2. In the Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Noble and Aristocratic Circles

- 2.1.3. In Jesuit Historiography

- 2.2. Thematic Scope of the Narratives

- 2.2.1. Myth of Origin

- 2.2.2. Christian Interpretation of the Tribal Past

- 2.2.3. A History of Belligerent Warriors

- 2.2.4. Bulwark and Shield of Christianity

- 2.3. Settings

- 2.4. Conclusions

- 3. Patron Saints

- 3.1. Confessional Patterns in the Hungarian Kingdom

- 3.1.1. Christianization

- 3.1.2. Ecclesiastical Structures and the Cult of Patron Saints

- 3.1.3. Reformation and Counter-Reformation

- 3.1.4. The Habsburgs in Hungarian Religious Affairs

- 3.2. Holy and Tutelary Patrons of the Kingdom of Hungarians

- 3.2.1. The Virgin Mary

- 3.2.2. St. Stephen and St. Emeric

- 3.2.3. St. Ladislas

- 3.2.4. The Hungarian Heaven

- 3.3. Conclusions

- 4. Rulers of Hungary

- 4.1. Principles of Hungarian Kingship

- 4.2. Narrated Kingship

- 4.2.1. The Royal Bodies and their Gestures

- 4.2.1.1. The Female Body

- 4.2.1.2. The Imperial Body

- 4.2.1.3. Royal Body Enthroned

- 4.2.1.4. Standing Pose

- 4.2.1.5. The Royal Body Mounted

- 4.2.1.6. The King’s Body Never Rests

- 4.2.2. Insignia of Rulership and Royal Emblems

- 4.3. Conclusions

- 5. Nobility and Aristocracy

- 5.1. Origins, Strata and Custom

- 5.2. Legal Status

- 5.3. Membra Sacrae Coronae

- 5.4. Imagined and Imaginary Kinship

- 5.4.1. The Cult of Ancestors

- 5.5. The Faces of Contemporary Nobles and Aristocrats

- 5.5.1. Warriors and Statesmen

- 5.5.2. Noblewomen

- 5.5.3. Men of Letters

- 5.6. Conclusions

- 6. The Afterlife of Illustrated Books on Hungarian History

- 6.1. Uses of Books and their Role in Identity-Building-Processes

- 6.1.1. Different Uses of Thuróczy’s Chronicle

- 6.1.2. Mausoleum and Trophaeum in the Seventeenth to Twentieth Centuries

- 6.1.3. The Afterlife of Illustrated Lives of Saints

- 6.2. Conclusions

- 7. Final Conclusions

- 8. Abbreviations

- 8.1. Libraries

- 8.2. Periodicals

- 8.3. Catalogues, Dictionaries and Collections of Texts

- 9. Bibliography

- 9.1. Sources

- 9.2. Literature

- 10. List of Figures

- 11. Index

Nothing made me more aware of the importance and sensitivity of personal names in identity studies than the street signs in Budapest changing before my very own eyes. Especially in the chronological and geographical scope discussed here, many local variants of names functioned in the region and found their reflection on the pages of the books studied. One of the most striking examples is that of the multilingual printing centre of Trnava (Hungarian: Nagyszombat, Latin: Tyrnavia, German: Tyrnau). In the current scholarship there is no widely accepted consensus about which form is preferable when writing in English. For the convenience of the reader, I will use the modern names of localities which can be found on contemporary maps (Brno, Székesfehérvár, Trnava) and give their English equivalents if such exist (Nuremberg, Vienna). I have avoided only place names that are strikingly anachronistic and were created in the nineteenth and twentieth century, such as Bratislava (until 1919 Slovak: Prešporok, German: Pressburg, Hungarian: Pozsony) or Budapest (which before 1873 existed as three separate cities: Óbuda, Buda and Pest), and in these cases I will refer to the Hungarian versions of the names from the era under investigation.

Personal names of historical figures also often functioned in several versions within one text, one language or one academic tradition. Today’s Matthias Corvinus (English) is Hunyadi Mátyás (Hungarian), Matei Corvin (Romanian), Matija Korvin (Croatian), Matej Korvín (Slovak), or Matyáš Korvín (Czech). Using the Latinized version of the name would be the closest to the pre-modern usage among the litterati, but this could be somewhat confusing for readers today. In what follows I try to balance between the custom in the English-speaking scholarship and the versions of the names accepted in Hungarian historiography. Following (often intuitively) this principle, I will speak of Hungarian writers and of most historical figures, apart from saints and kings, using the Hungarian version of their names: János Thuróczy (Johannes de Thurocz, John Thuroczy, etc.) and János Hunyadi (instead of Johannes or John Hunyadi). Similar rules are adopted in the case of Polish, Croatian and Italian authors and historical figures, following the respective national tradition of scholarship. One exception is inter alia the magyarized Croat Miklós Zrínyi (1620–1664), who had a Hungarian mother, and who became an influential person in Hungarian (and Hungarian-language) literature and politics. In such complex cases I use the Hungarian name of a person. However, when speaking about kings and saints I will use the English equivalents of their names, following the variants given by Pál Engel’s The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary 895–1526.1

To facilitate identifying a particular person, placing them in time, and distinguishing namesakes from the same family, I provide the dates for the pontificates of popes, reigns of kings, emperors (referring to the dates of their rule in Hungary) and sultans in parentheses; in all other cases only the date of birth and death of the particular person is provided. For Hungarians I follow the data provided by MaMűL, where possible.

Finally, I have to mention the editorial principles which I have applied in regard to Latin excerpts quoted in the main body of the dissertation. In the main corpus of sources ← 11 | 12 → only one book has a critical edition – János Thuróczy’s Chronica Hungarorum – and I refer to this edition.2 As regards the remaining, mainly seventeenth century sources, I attempted to cite the authentic text of the printed original along with its late medieval and early modern peculiarities to do justice to the specific way in which Latin was used in these periods. No attempt was made to normalize the Latin. Only the most obvious typographical errors were corrected. In the case of eulogies the versification is observed.

This work is a revised version of my doctoral thesis, which was the outcome of a captivating, four-year journey into Hungarian culture completed during my PhD studies (2010–2014) at the Faculty of “Artes Liberales”, University of Warsaw.3 On this journey I could always rely on the cordial company and encouraging support of numerous leading specialists in a field in which I have only made my first steps. I am deeply indebted to the invaluable and continuous assistance of my supervisors Grażyna Jurkowlaniec and Jerzy Axer, whose inspiration is clearly visible throughout the book. I would also like to express my profound gratitude to the reviewers of my dissertation, namely Gábor Klaniczay, Katarzyna Marciniak and Juliusz Chrościcki for their indispensable comments and suggestions in transforming my doctoral thesis into this book. I owe thanks also to Áron Petneki, Enikő Békés, Szabolcs Serfőző, Wojciech Kozłowski, Géza Pálffy, Maria Poprzęcka and Robert John Weston Evans, who kindly agreed to discuss with me excerpts large and small of the previous drafts of this work. This list must be expanded to include all the staff and members of the doctoral Programme in which I participated – the International PhD Projects (MPD) financially supported by the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP) – who provided me with helpful hints and remarks at my presentations of subchapters delivered at MPD seminars. Among them Jan Miernowski, Szymon Wróbel, Ágnes Máté and Aleksander Sroczyński must be mentioned. I owe separate thanks to Katarzyna Jasińska-Zdun for spell-checking the Latin excerpts of the thesis, to Andrzej Sadecki for reviewing my translations from Hungarian, and to the faculty librarian – Tomasz Chmielak for his assistance.

Without the financial support of the FNP it would not have been possible for me to carry out research and internships at the Central European University in Budapest (CEU, 2012–2013, 2014) and Oxford University (2011–2012). I cannot overstate the benefits of the time spent in these two inspiring academic environments and at the Hungarian National Library in Budapest (work in which was greatly facilitated by the help of the head of the Rare Book Collection Gábor Farkas), Special Collection of the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Special Collection of the Library of Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) and the ELTE-CEU Medieval Library, with their incredibly patient and always helpful librarians, for the subsequent analyses. ← 12 | 13 →

Finally, I would like to acknowledge the enormous support of the first and the most critical reader of every part of this thesis – my husband – without whom this work would never have reached its final stage, or might not have ever been started at all.

Needless to say, I alone am responsible for whatever errors or defects found their way into the text.

1Pál Engel, The Realm of St. Stephen: a History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526, trans. Tamás Pálosfalvi (London: I.B. Tauris, 2001).

2János Thuróczy, Chronica Hungarorum, eds. Erzsébet Galántai, Gyula Kristó (Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 1985–[1988]), 3 vols: I: Textus; II and III: Commentarii: I Ab initiis usque ad annun 1301; II Ab anno 1301 usque ad annum 1487.

3The excerpts of the introductory sections and part of the fifth chapter were published as a separate paper: “Illustrated Books on History and their Role in the Identity-building Processes: the Case of Hungary (1488–1700)”, in Early Modern Print Culture in Central Europe, eds. Stefan Kiedroń, Anna-Maria Rimm, in co-operation with Patrycja Poniatowska (Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego, 2014), 21–38.

Imprint this in thy memorie.

A Panoplie of Epistles, or, a Looking Glasse for the Unlearned,

London, 1576, 24.

1.1 Concepts and Research Problems

The winner of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1973, Konrad Lorenz, observed the instinctive behaviour of animals and noted that they are innately responsive to particular stimuli. Ducklings and goslings proved especially susceptible to a mechanism that resulted in trust in another animal, human or even an item (such as Lorenz’ famous gumboots), on which a very young bird fixes its attention. As a result of the earliest visual, auditory, or tactile experience this object was taken by them as a parent. As a consequence of ‘imprinting’, as Lorenz calls the process, these young animals regard themselves as belonging to the same species (or category of things) as their supposed mother or father. In these cases, ‘imprinting’ concerns the instinctive behaviour of organisms, which directly, and often irreversibly, affects their personal identity.

It has been argued that human children are also susceptible to various types of ‘imprinting’ which affects their mating and sexual preferences. The scholars in favour of this hypothesis claim that adults are likely to prefer partners resembling the individuals who reared them. Studying mating choices, they observed a physical similarity between the preferred partners and the opposite-sex parent.4

More pertinent for the following reflection, however, are those behavioural patterns which affect the mentality of adults. In this context ‘to imprint’ means to ‘to impress (a quality, character or distinguishing mark) on or in a person or thing.’5 Closely related to this operation is the process of ‘impressing or fixing something in the mind or memory’, which means to ‘consider or remember something carefully’.6

The process of imprinting concerning larger social groups (mainly organizational units) at a longer time span is discussed in organizational theories dating back to the early 1960s. They focus on the ways the foundational political, cultural, economic and technological circumstances of the organization determine its further existence. By so doing they analyse the mechanisms affecting reproduction of the organizational patterns in the course of the organization’s existence. The focus of such studies lies in the founding phase of the organization along with its time- and place-specific conditions and the modes of its later functioning. Hence, the theory of organizational imprinting provides a useful framework for a study on the ways in which the initial forms of peoples’ social existence determine their subsequent duration.

What interests me in connection to all these mechanisms which affect peoples’ ways of behaving and self-perception is yet another process of ‘imprinting’ understood ← 15 | 16 → as to ‘print’, to ‘delineate by pressure’.7 This term encompasses the manufacturing of early printed books and their illustrations. When considered with the previous meanings of the word in mind, it also alludes to their potency of life – recalling the words of John Milton – i.e. to their capability to evoke numerous responses from recipients. Here lies the main objective of this work, namely demonstrating that illustrated books participated in discursive processes forming the individual and collective identifications of their readers and viewers. The visual and literary content of the books – I will claim – empowered certain narratives, which proved to have a long-lasting impact on generations of their users.

Today’s books are overloaded with images, graphs and charts which are thought to draw the reader’s attention. Despite this I can recall but a few illustrated books which irreversibly imprinted on my memory. Among them a distinctive place is held by Poczet królów i książąt Polski [Gallery of Portraits of Polish Kings and Princes] with illustrations by Jan Matejko (1838–1893).8 The book was and still is an obligatory volume in every Polish household. I do not remember reading the biographies of any king, but I can recall with great ease each picture from the book. Even today, when thinking of the history of the Polish Kingdom, I picture every ruler according to Matejko’s drawings. The example of images from Poczet królów, which found its way onto banknotes, coins, postage stamps and into numerous schoolbooks, both directly and indirectly influencing the historical imagery of Poles, raises the question of the ways in which illustrated books on history functioned in times and cultures in which publications with illustrations were luxuries and rare commodities. What was their place in literary and visual communication? Did they make a larger impression on recipients less used to this medium? If so, what was their involvement in identity-building processes?

With the last question, of central importance for this work, I enter the debate about identity issues, one of the most promising and challenging fields in today’s scholarship. The current academic interest in identity studies may be partially explained by the need to bridge a precipice, one edge of which is marked by the advent of biomedical technologies (DNA profiles, iris recognition, etc.) with their abilities to precisely define individual identities, and another by the current ‘collective identity crises’ caused by the fashion for a highly individualistic pose, and to a larger extent by the disintegration of the current identity models.9 There is also another current paradox of identity that scholars are attempting to understand. How is it possible that identity can be at the same time the source of pride and joy, strength and confidence, and the force that draws people towards bloodshed?10

In this context, studies on identifications of recipients of late medieval and early modern illustrated books may be perceived as an obscure, niche task. The selection of topic could therefore be viewed as objectionable. My decision was based on the conviction that answering such questions as: ‘with whom you identify yourself?’, ‘where do you belong?’, ← 16 | 17 → ‘how do you perceive your history?’ was not necessarily much easier five, four or three centuries ago in such a complex religious, social and political environment as St. Stephen’s Kingdom. Tracing the trajectories of the reception of the visual-cum-verbal message in the self-representations and visual surroundings of their readers and viewers and the ways in which the collective and personal identities were negotiated may shed light on the mechanisms of visual and literary communication in past centuries. Moreover, posing the question of identity in pre-nineteenth-century Central Europe may enrich the identity debate that is taking place at the moment in and outside Hungary and show that the issue of the national identity is not as recent as it is often thought.

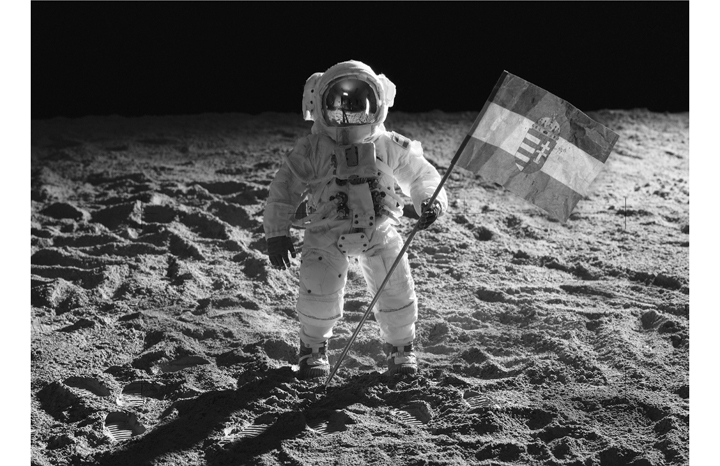

The current polarization and at the same time radicalization of the identity discourse running in parallel in Poland and Hungary provokes both a look beyond the public debates and a look back into history. The exhibition Mi a Magyar? [What is Hungarian?] organized in the Műcsarnok [Exhibition hall] in Budapest between July and October 2012 shows how pressing this issue is. The curator of the exhibition, Gábor Gulyás, attempted to present Hungarian identity as a prominent topic of public debate over the last two centuries. Nevertheless the selection of answers presented in the exhibition was predictable and somewhat disappointing for both poles of Hungarian society. Artistic reflection rarely stepped beyond a threadbare interpretation of the national symbols and legends, shared history, social hierarchy and the place of the individual within it. The shortcomings of the majority of the answers given by contemporary artists were evidenced by a lack of more polyphonic and nuanced voices. As a result the exhibition turned out to be too radical and not ‘national’ enough for political decision-makers and their supporters, as well as too simplified and manipulated for political discordant voices of their opponents.

The exhibition opened with a prominent work by the contemporary artist Gábor Gerhes entitled Magyar hold 1 [Hungarian moon 1] (fig. 1). Instead of Neil Armstrong, ← 17 | 18 → the work shows a Hungarian astronaut conquering space. The national flag with the Hungarian coat of arms clearly denotes the national identification of the astronaut. The fact that the scene is a mystification is revealed, however, by the reflection of a photographic studio on the cosmonaut’s helmet. The interpretations of the picture could follow numerous threads, beginning with unfulfilled ambitions, through the self-delusion and disillusionment of the Hungarian nation, the self-perception of the nation and its self-ironic character, up to the more general diagnosis of what being Hungarian means today. Magyar hold 1 does in my opinion have its precedents in earlier epochs and introducing them into the debate can considerably enrich the ongoing discussion.

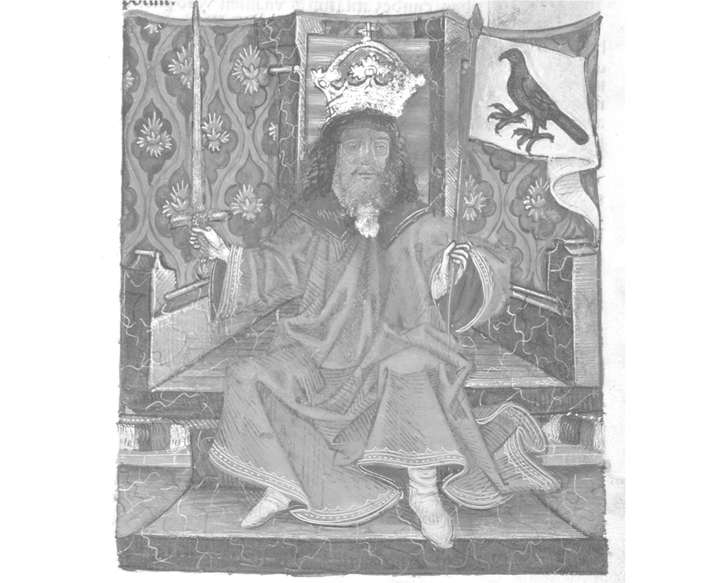

An image of Attila that illustrates the Augsburg edition of János Thuróczy’s Chronica Hungarorum of 1488 (fig. 2) offers a picture of another imagined conqueror and fabricated hero of the Hungarian nation. The juxtaposition of these two pictures opens a dialogic space of great interpretative potential. By analysing this and many other images from the incunabula and early printed Hungarian books I hope to demonstrate that such questions as ‘What is Hungarian?’ and ‘What it meant to be Hungarian?’ cannot be fully answered without bearing in mind the visual debate on issues of identity from the late Middle Ages and the early modern period.

Fig. 1: Gábor Gerhes, Magyar hold 1, 2011

Fig. 2: Attila, Chronica Hungarorum, Augsburg 1488, fol. b4r

Discussing manifestations of identities within literary and visual studies is a perilous enterprise. One working outside the sociopsychological or sociolinguistic field of research is exposed on the one hand to the danger of offering a simplified or too ← 18 | 19 → transparent picture of identity models and on the other hand to the risk of obscurity. The question that could not be avoided is thus: which definition of ‘identity’ could be used as an operational one for the needs of this study? How should one approach such a slippery and elusive phenomenon using visual-cum-verbal materials from the past centuries?

The most general definition of the phenomenon, proposed by Peter Burke and Jan Stets in the opening chapter of their work Identity Theory, states that:

Details

- Pages

- 314

- Year

- 2016

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653061369

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653954333

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653954326

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631669921

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-06136-9

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2015 (November)

- Keywords

- visual communication print culture illustrated books identity discourse historical narratives

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2015. 314 pp., 83 b/w ill.