The World of Stephanie St. Clair

An Entrepreneur, Race Woman and Outlaw in Early Twentieth Century Harlem

Summary

Upon arrival in the United States St. Clair did not conduct her life in the manner expected of a black female Caribbean immigrant in the early twentieth century. What factors influenced St. Clair’s decision to become an entrepreneur and activist within her community? Why did St. Clair describe herself as a «lady» when ladies did not run illegal businesses and they were not black? These questions are explored along with her lineage – a lineage that contains the same fighting spirit that she carried throughout her life. This is not the story of a victim.

Courses concerned with the study of social and economic conditions of black urban residents during the early twentieth century and female entrepreneurs of the same era will find St. Clair’s story compelling and informative.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

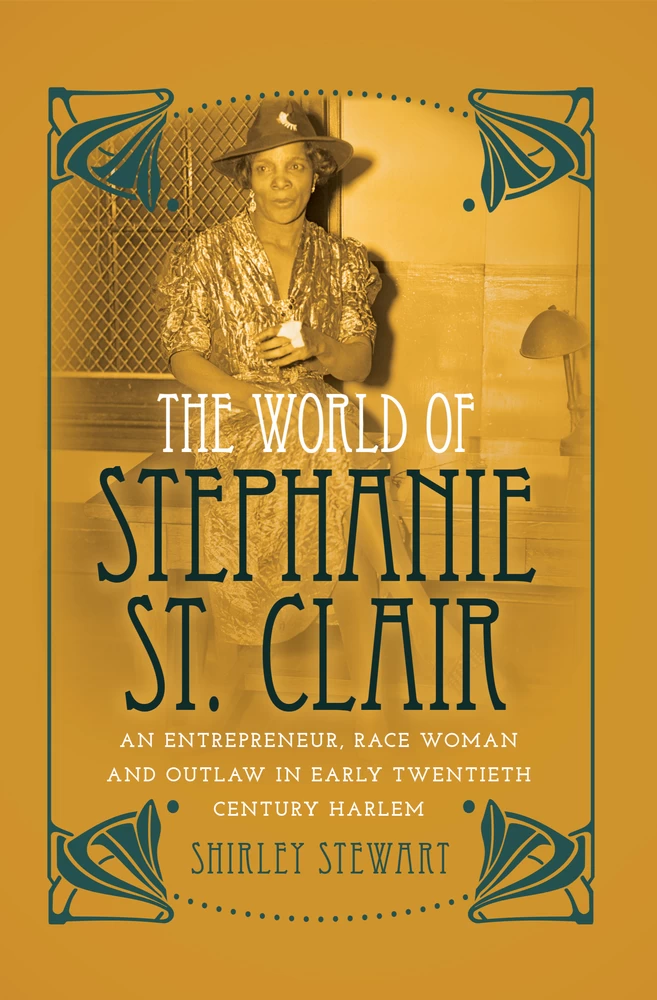

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- One: The Old World

- Where It All Began

- The Journey

- Lady

- Two: The New World

- America

- Satan’s Seat

- Harlem, USA

- Three: The Business and the Politics of Policy in Harlem

- The Business

- The Politics

- Four: Activism, Sufi and Survival

- Activism

- “Darling” Sufi

- Survival in the New World—Again

- Conclusion

- Final Thoughts

- Notes

- Introduction

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Newspapers, Magazines and Journals

- Archival Documents

- Testimonials, Legal Decisions, Reports and Official Documents

- Transcripts and Videos

- Articles

- Books

- Index

- Series index

← x | xi → ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book was nothing but a vague idea as I worked toward my masters and it would not have been possible without a few key individuals.

Priscilla Murolo questioned and challenged me on the subject until the idea became something of substance, something worthy of a thesis.

Gina Luria Walker gently guided me through the initial research and writing process. Whether it was a better word or phrase in a paragraph or offering words of wisdom, she always made the work sharper and more focused.

Katherine Butler Jones shared her knowledge of Stephanie St. Clair with me. Her recollections were much appreciated.

Marsha Darling worked with me to turn my thesis into a book. She was an unfailing champion of this project and led the way toward publication.

I am grateful for the professionalism of those at Peter Lang Publishing who brought this text—vision intact—to fruition.

Many thanks to the librarians and archivists at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the New York Public Library, the New York State Archives, the Mount Vernon Public Library and the Esther Raushenbush Library at Sarah Lawrence College.

Finally, thanks to my daughter, Simone. She has been an unwavering source of encouragement and support. She also learned to eat dinner on the ten-inch square left on the dining room table that did not have a book on it. ← xi | xii →

← xii | 1 → INTRODUCTION

In 1923, with $10,000 in seed money, Stephanie St. Clair launched and ran a highly-lucrative policy bank in Harlem that earned a quarter of a million dollars a year.1 To this day, she remains the only black female gangster to run a numbers racket of that size. The larger operations run by mobsters Dutch Schultz and Lucky Luciano actually saw a decline in earnings during the same years. Schultz, realizing the financial potential of “numbers running” in Harlem, invited himself to share in the proceeds of one of Harlem’s most lucrative businesses.

Unlike other Harlem policy bankers, St. Clair was not intimidated by Schultz. She declared on the front page of the New York Amsterdam News, “I’m not afraid of Dutch Schultz or of any other man living. He’ll never touch me!”2 One might speculate that she should have been afraid—Schultz was a ruthless man. At the time, reports surfaced that Schultz tried to murder her on at least three occasions. St. Clair was strong and ruthless as well and his attempts to execute her only fueled her contempt for him. St. Clair expressed her disdain by physically destroying Schultz’s base of operations and supplying information to government authorities. St. Clair made sure that Schultz knew she was the source of that information by discussing her activities with newspaper reporters.

Despite Schultz’s threats, many of St. Clair’s employees remained with her. Some said she paid unusually high wages and challenged her employees, who were overwhelmingly male, by asking, “You are men and you will desert me now? What kind of men would desert a ← 1 | 2 → lady in a fight?” Who was this lady who feared no man?

Stephanie St. Clair was born in 1897 on the island of Guadeloupe. Upon arrival in the United States in 1911 she could have acquiesced and led her life in a manner expected of a black female Caribbean immigrant. Under pressure to conform, St. Clair could have allowed others to determine her path in life. During the period (1911–1914) when St. Clair arrived in New York, 4,9433 other black women arrived in the United States, the majority bound for domestic servitude. Research confirms that she too was destined for the same fate.

My core question then is why did she not embrace and live the life expected of her? What were some of the “knowable” factors that influenced St. Clair’s decision to become an entrepreneur who created and managed her own illegal business and, paradoxically, become an activist within her community? An additional focus of my inquiry concerns St. Clair’s decision to describe herself as a “lady” when the definition would not have applied to her—ladies did not run illegal businesses and they were not black.4 In this historical examination of the life and legacy of Harlem’s most famous woman policy banker, I argue that the answers are at the nexus of what St. Clair believed herself to be and the influence of external factors on her life.

The first challenge to exploring St. Clair’s life concerned the definition of “entrepreneur.” In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the word usually referenced men in business as most black women labored at the bottom of the labor force.5 The scholarly lens used in this study of Stephanie St. Clair considers the intersection of race, gender and class. The term “womanist” was not yet in existence a hundred years ago, but black female entrepreneurs like St. Clair nonetheless provided an initial working definition.6 In considering the historical legacy of the black woman’s experience—personally and collectively—many developed emotional mechanisms that allowed them to contribute to their families and communities despite the racist standards that existed. Many black women developed the ability to reject the notion of their inferiority as blacks and as women. They harnessed a determination to seek employment and education for themselves and their families while marshaling personal strength that contributed to a collective force to help their communities.7 As a ← 2 | 3 → black person, St. Clair aimed higher than working in domestic service. As a woman, she entered an underworld that was almost exclusively male and, utilizing her entrepreneurial talent, created and ran a successful business. Lastly, St. Clair risked moving out of the societal place assigned to her as a “Negro” and moved into a space traditionally occupied by whites.

Another challenge to my exploration of St. Clair was the scholarship on early business development among blacks. One notion posited that they lacked business acumen. St. Clair was indeed successful yet as late as 1957 sociologist E. Franklin Frazier theorized that the small profits generated from black businesses was a result of a lack of business tradition and limited support from black consumers.8 Dispelling this inaccuracy has been an ongoing process. In fact, historians studying bondwomen argue that the African and Creole in America used their business acumen even while enslaved. Deborah Gray White’s seminal study of enslaved women in the plantation South reveals clandestine entrepreneurial-like cooperative networks the bondswomen formed with each other in order to assuage the effects of a brutal plantocracy. After their emancipation, black women continued to keep secret their businesses and their networks because visible signs of success might have proved dangerous—especially in the American South. Subsequent scholarship has further bolstered White’s conclusions that secrecy, in conjunction with the prejudice of low expectations, obscured the extent of black women’s economic networking from researchers who also were not looking to find such social and business achievement.9 However, these networks were certainly in evidence on the island of Guadeloupe as bondswomen conducted business and fought against slavery on the plantation and in the courts.

Scholars studying black female entrepreneurs agree that entrepreneurial business activity among black women began in Africa where they were not just consumers but active participants in their communities’ economies.10 African entrepreneurs, both men and women, created their business in order to support their families and communities while, in turn, counted on the support of family and friends to help fund their endeavors and lend a hand with childcare. They also formed strategic alliances with other business owners and ← 3 | 4 → neighbors to increase profitability. In the case of St. Clair and policy banking, this interdependency existed in Harlem as well. Before the intrusion of white organized crime syndicates, playing the numbers was a non-violent activity that provided entertainment and an opportunity to earn money. Whether an individual chose to create a policy bank as St. Clair did, work for a policy banker or simply play the numbers, there were no constraints on who could enter the business as long as they restricted their activities to Harlem—there was room for everyone. Harlem policy bankers (known as “kings” and “queens”) earned huge profits and, in turn, funneled money back into the community. In fact, they often provided needed financial support that municipal entities failed to make available to residents.

But one wonders how St. Clair was viewed by others during an era when gender roles were clearly defined and strictly enforced. Historian Angel Kwolek-Folland suggests that women, as a whole, were ultimately restricted in their role as entrepreneur by motherhood and assumptions about gender, even though the “mother as manager remains a powerful business image, one manifestation of the continuing strength of the family claim.”11 It is difficult to ascertain how many female policy bankers operated in Harlem but they were in the minority.

St. Clair was quite unique among women and that may have explained her success. First, she was not constrained by family obligations. At the time that she began her bank she was an unencumbered young woman able to put all of her energy into her venture. St. Clair also had the necessary funding available. Generally, black women did not have access to large amounts of start-up capital. Finally, St. Clair had the business skills (probably from working as a functionary for another policy banker) unlike many black women whose professional experience was limited to work in the domestic sphere. Because of that success, she may have been able to circumvent the “assumptions” about gender. However, she was not above chastising her community in a somewhat motherly fashion utilizing the “mother as manager” image Kwolek-Folland refers to.

Adaptability in these entrepreneurs also garners interest from historians. Kwolek-Folland’s Incorporating Women examines this characteristic by placing her subjects in the context of their environments. ← 4 | 5 → As their societal situation changed—often to their detriment—black female entrepreneurs formulated and revised their business strategies to benefit from those changes. St. Clair shared this characteristic with two contemporaries, Madam C.J. Walker and Maggie Lena Walker.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 190

- Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453912720

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454197782

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454197775

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433123870

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433123863

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1272-0

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2013 (November)

- Keywords

- bank female gangster immigrant policy bank gangster activist

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2014. XII, 190 pp.