A Heaven of Their Own

Heresy and Heterodoxy in Portuguese Literature from the Eighteenth Century to the Present

Summary

Portugal is a country shaped by successive waves of occupation over the centuries, and by the religious transformations these have entailed. Indigenous Lusitanians and Celtiberians withstood invasions by the Romans, Visigoths and North African Moors, as well as visitations by Jews, Phoenicians and others, but all were eventually killed, driven out or obliged to convert to Christianity. This book investigates texts dating from the eighteenth century to the present and set in periods ranging from the third century BC to the present day, in which the encounter between Paganism, Judaism and Islam, on the one hand, and what in due course became the dominant Christian status quo, on the other, illustrates the former’s resistance to absolute erasure. The study focuses in particular on women as the locus of dissent at the heart of national and sexual politics.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: Religious Difference in Portuguese Literature: God’s Infinite Variety

- Chapter 2: Pagans One and All: Teresa de Mello Breyner and Domingos Monteiro

- Chapter 3: Moors on the Shore (Há Mouros na Costa): Alexandre Herculano and Hélia Correia

- Chapter 4: The Jew in You: Camilo Castelo Branco and Miguel Torga

- Chapter 5: Standing in My Relative’s Shoes: Christianity on a Crucible: José Saramago

- Epilogue: In the End Was No Word: Old Tragedies for Modern Times

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Life is patently not fair and I benefit from that unfairness: religion has never been an emotion I understand, which makes me an undeserving beneficiary of the numerous good Samaritans and guardian angels that make my life lovely and as calm as possible. Alphabetically, more or less: David Bailey, former student, research assistant, colleague and now friend; John Beer, a model cleric who proves that absolutely everything I say in this book about Christianity and Christian men is simply wrong; Susan Beer, who gives me metaphorical clips around the ears and is quite right to do so; Victoria Best, the loveliest of friends, who is always on my side; Janet Chow, Colin Clarkson, Fiona Colbert, Hélène Fernandes, David Lowe, Sonia Morillo Garcia and Mark Nichols (I did say more or less alphabetically), magician librarians who have such mysterious ways of finding things that in the bad old days they would have been burnt at the stake; Margaret Clark and Ken Coutts for too many things to list; Céline Coste Carlisle who always gets love right; Chris Dobson who gave me time he did not have at the worst time of my life; Mary Dobson for being who she is and for that school sports day (among other things); Peter Evans and Isabel Santaolalla who always drop absolutely everything for me and Laura and who really know how to love; Robert Evans, my extremely youthful old friend; the Gentlemen (and one Lady) Porters of my College, who pick me up when I fall, laugh at me, rescue me all the time, make me laugh and make the start of every day sweet and lovely; Philippa Gibbs, the most generous friend in the world; Margaret Jull Costa who loves what I love; Simone Kuegeler Race who has listened to me screaming in pain at the hands of Nurse Diesel/Nurse Ratchett; Ádela Lisboa, Ana Cristina Lisboa and Zé Rodrigues, my lovely and loving relatives; Teresa Moreira Rato, my friend whether I’m right or wrong (since we were five years old, which covers a lot of wrongs); Coral Neale for being Coral: without her our department would cease to exist; Máire Ní Mhaonaigh for absolutely everything, from love to practical to intellectual support to a relentless willingness to just be ← ix | x → there for me; John O’Sullivan, Aicha Rehmouni, Farida Hadu, Jack Glossop, Des O’Rourke and Jamie Pineda (and with fond memories of Jean-Pierre Laurent: ‘Madame, time is nussing I am wiz you’); John Rink, the man of my dreams, who does my washing up so beautifully. Helen Watson, for lovely times, friendship and tracking down references to war and sorrow. And with love to Laura Lisboa Brick, of course.

Beyond our ideas of right

and wrong, there is a garden.

I will meet you there.

When the soul lies down

In that grass, the world is

Too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the

Words ‘each other’ don’t

Make sense anymore.

— JALĀL AD-DĪN MUHAMMAD RŪMĪ

They paved Paradise

And put up a parking lot.

— JONI MITCHELL

For I myself saw the Sibyl indeed at Cumae with my own eyes hanging in a jar; and when the boys used to say to her, ‘Sibyl, what do you want?’ she replied, ‘I want to die.’

— PETRONIUS

Imagine there’s no heaven

It's easy if you try

— JOHN LENNON

If in that Syrian garden, ages slain,

You sleep, and know not you are dead in vain,

Nor even in dreams behold how dark and bright

Ascends in smoke and fire by day and night

The hate you died to quench and could but fan,

Sleep well and see no morning, son of man.

But if, the grave rent and the stone rolled by,

At the right hand of majesty on high

You sit, and sitting so remember yet

Your tears, your agony and bloody sweat,

Your cross and passion and the life you gave,

Bow hither out of heaven and see and save.

— A. E. HOUSMAN

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

[…]

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

— W. B. YEATS

This earth cost us ten heavens.

— OSIP MANDELSTAM

← xi | xii →

In 1994 I attended a talk in my college in Cambridge, St John’s, given by the Norwegian anthropologist Tone Bringa. At the time when the war broke out in Yugoslavia in 1991, Bringa had been studying ethnically and religiously mixed communities in Bosnia for some years. Following the death of Josip Tito in 1980 and the subsequent break-up of Yugoslavia, the country descended into a violent civil war between different ethnic and religious groups, and old friends and neighbours turned into murderous enemies. We Are All Neighbours is a 50-minute Granada Television documentary filmed by Bringa and co-director Debbie Christie in a traditionally Muslim/Croatian village over a period of some years, both before and after war broke out in the region.1 It focuses on the relationships between Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) and Croatian Catholics, and in particular those of women in a village 7 kilometres from Kiseljak, northwest of Sarajevo. Bringa began studying the village in the late 1980s before the beginning of the war, continued both after the conflict had broken out elsewhere in the country but had not yet reached the village, and finally after it had, resulting in the killing of Muslims or their flight to nearby locations. Before the outbreak of hostilities she had documented what had been an exemplary demonstration of the dictum that ‘it takes a village to raise a child’: she had focused principally though not exclusively on a close-knit community of Muslim and Catholic women united by bonds of friendship and mutual support. As war broke out between different ethnic and religious groups elsewhere in the country the village women were adamant that their relationship, stretching back many generations, would not be affected by political changes on the outside. This was proved wrong. Bringa returned to the village in 1993. By that time, the Muslims that had not succeeded in fleeing the village were living in a state of siege on top of a near-by hill. Bringa attempted but failed to set up a dialogue between two of the women, one a Catholic and one a Muslim, who had shared a particularly strong friendship and whom she herself had befriended over the years. But by then, two old friends who had known each other since childhood no longer trusted ← xii | xiii → one another with their lives. Although religion was by no means the only factor in what became the first instance of genocide in Europe since World War II, it was certainly a key component. In that respect, it joined the roll of honour of a long and dirty list of murders committed in the name of God in the course of human history.

1 Tone Bringa, and Debbie Christie, ‘We Are All Neighbours’, Disappearing World Series. UK and Bosnia: Granada Television (1993). <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uip50amKMdw> (accessed 4 July 2017).

Religious Difference in Portuguese Literature: God’s Infinite Variety1

I think it is especially misguided to kill people in the name of God.

—AUDREY NIFFENEGGER (interview)

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. […] We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant.

—KARL POPPER, The Open Society and Its Enemies

← 1 | 2 →

Ghastly illusion of eternity,

Terror of the living, dungeon of the dead,

Senseless dream of aimless souls, its name is hell;

A system of oppressive rule,

Bridle which the hand of despots, of hypocrites,

Forged for foolish belief; […]

No, your darkness does not haunt me.

— MANUEL MARIA BARBOSA DU BOCAGE, ‘The Ghastly Illusion’

ABSTRACT

This introduction sets out the argument to follow by outlining the general rationale. It identifies the texts to be considered: Teresa de Mello Breyner’s Osmia; Domingos Monteiro’s Letícia e o Lobo Jupiter [Letícia and the Wolf, Jupiter]; Alexandre Herculano’s Eurico o Presbítero [Eurico the Presbyter] and ‘A Dama Pé Cabra’ (‘The Lady with a Cloven Hoof’); Hélia Correia’s ‘Fascinação’ [‘Enchantment’]; Camilo Castelo Branco’s O Judeu (The Jew) and O Olho de Vidro (The Man with a Glass Eye); Miguel Torga’s ‘O Alma Grande’ [‘Big Soul’] and ‘O Milagre’ [‘The Miracle’]; José Saramago’s O Evangelho Segundo Jesus Cristo [The Gospel According to Jesus Christ] and Caim [Cain].2 It sketches the principal historical timelines and identifies the themes (women, religion, patriarchy and dictatorship) and the theoretical framework (New Historicism; aspects of Feminist Theory) to be drawn upon.

In the Name of God

The present study is the result of conclusions drawn from years of teaching and research on a wide spread of literary texts ranging over historical periods that, as regards their authors, reach from the eighteenth century to the present, and, regarding the narratives’ chronology, go back as far as the third century BCE At the heart of these conclusions lies the realization that, in the territory that is now Portugal, religious strife was not a two-way ← 2 | 3 → street, aggression having almost always been most sustainedly and aggressively directed by Christians against other faiths.3

*******

At this point it is necessary to make a brief digression to explain why in what follows I shall mostly use the term ‘Roman Catholic’ rather than just ‘Catholic’ or ‘Christian’. There are two reasons for this. First, a cultural one: in Catholic countries such as Portugal, religious people invariably describe themselves simply as Catholics: not Roman Catholics or even Christians; in Anglophone countries, on the other hand (and this book is, after all, written in English and published in the UK), the term ‘Roman Catholic’ is commonly used. It dates back to the rise of Protestantism in Europe, and in England (as it then was), specifically to the schism with Rome instigated by Henry VIII, an epoch-making event that severed Christianity from Papal authority, relegated the Pope to the status of Bishop of Rome and declared the monarch and all his successors Heads of the Church of England. But even prior to that, from the very moment, indeed, that the Apostles set out on their separate travels to spread the Good News, Christianity had split into many different branches, including the Orthodox Churches (the Greek, possibly founded by Peter and the Russian, supposedly founded by the Apostle Andrew). Others, less well known, were also supposedly founded by Apostles other than Peter and Paul (themselves the two founders of the Church in Rome, where Peter was eventually martyred, under the rule of Nero). The churches founded by the other Apostles, therefore, were not linked to Peter as the first Bishop of Rome (Pope) although mostly they retained the denomination of ‘Catholic’. They include the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria (supposedly founded by Mark), the Patriarchal Coptic Catholic Church, the Patriarchal Chaldean Catholic Church, the ← 3 | 4 → Patriarchal Melkite Catholic Church (within which the followers of Jesus were first called Christians), as well as several others.4

The second reason for my emphasis on the term ‘Roman Catholic’ is motivated by the fact that several of the authors discussed here regarded themselves as either Christian or of unspecified spiritual beliefs whilst maintaining a position of outright hostility to the (Roman) Catholic Church and to Papal authority – the Vatican.5

*******

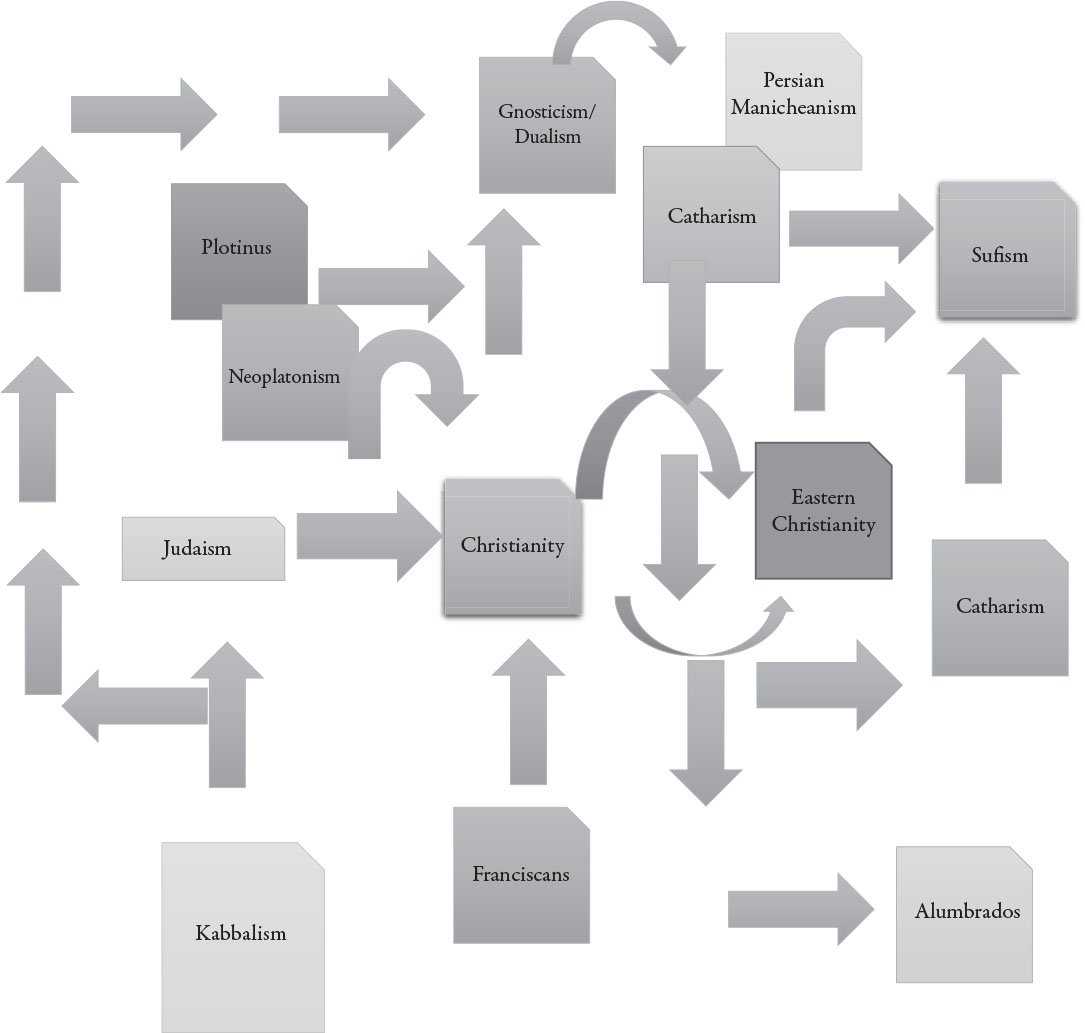

Over the past twenty-five centuries the Iberian Peninsula underwent many strata of occupation. The original Lusitanian and Celtiberian inhabitants withstood waves of conquest and occupation, or at least visitation, by Romans, Visigoths, Greeks, Phoenicians, North African Moors and Jews, some of whom converted to Christianity, with the latter in due course establishing hegemony over the entire territory. Each wave of occupation left distinct and important traces in the region’s ethnicity, language, cultures, legislation and forms of religious worship. Until the advent of Christianity as the dominant religion, the different faiths, following what was sometimes, admittedly, bloody conquest, on the whole co-existed in relative harmony, in a relationship of mutual influence. The establishment of Roman Catholic dominance put an end to this and began a centuries-long process of elimination of religious pluralism.

Re-capitulating back to the ancient Peninsular past, in the third century BCE the Late Antiquity Lusitanian and Celtiberian forms of religious worship gave way to Roman Paganism, the latter subsequently converting to Christianity, only to be itself overrun by the central European faiths of the Visigoths, Vandals, Arians and Suevi, which themselves in due course also converted to Christianity. The Iberian Christian Visigoths were ← 4 | 5 → subsequently overrun by Islam, then a newly minted religion which was itself only driven out of the land after the long centuries of the Reconquista. The last Moors were driven from the Algarve (to whose presence, however, the name’s etymology still bears testimony)6 and from the territory that comprises present-day Portugal in 1249, two and a half centuries before similar events in Spain.7 And all along, certainly since the early days of the Roman conquest of the Peninsula, but possibly even earlier, there were Jews. Each religion in turn, after an initial period of bloody conquest (the latter, however, inapplicable to Jews who were always minority settlers rather than conquerors), gained control but co-existed with, and to a greater or lesser extent protected the existence of its various Others, before being itself superseded. The notable exception was Christianity, which, from its earliest times of domination remained unwilling to pursue anything other than a proselytizing and usually persecutory rule. This continued to be the case even when, following its triumph in the sixteenth century, what was left were not just the crushed followers of different faiths but even those of none. It is these modes of not being Christian, and the consequences of it under Roman Catholic rule that will be considered in the texts to be discussed in this book.

Prior to studying the narratives and what they may have to reveal to us, it is necessary to offer an outline, albeit schematic, of the relevant historical timelines, and of some of the religious and political forces at play in the periods in question. The authors studied in the chapters that follow all wrote at times of heightened power exercised by the Roman Catholic Church (namely the Holy Inquisition, the post-Pombal era and Salazar’s twentieth-century Estado Novo), under all of which Concordats were signed with the Vatican, legally binding state and church law. Their works, directly or indirectly, allude to the intransigence that made the religious status quo (actually or by implication Christianity) the least willing of all the faiths to compromise with other creeds, let alone incorporate aspects of them into its own precepts. The latter possibility, indeed, in the form of the mutual ← 5 | 6 → absorption of alternative practices from other faiths, was something that the Christian Church actively sought to suppress from the beginning. Over the centuries, as the Roman Catholic juggernaut overcame the practitioners of non-Christian faiths or of no faith, religious zeal instigated, time and again, a drive to homogeneity practiced at times with extreme violence. Even under these sub-optimal conditions, however, residual traces of different practices endured, as will be discussed in subsequent chapters. For the moment it may suffice to say that the most worshiped manifestation of the Marian cult in Portugal involves a rendition of the Virgin Mary associated with a Moorish figure: Fátima, or Fatimah, daughter of Mohammed, was the founder of Shia Islam in the seventh century, long before, in her most Christian guise as Our Lady of Fátima, she appeared to three young children at Cova da Iria, a hollow near the town that gave her that moniker (see Chapter 3).

In the chapters that follow, detailed introductions will be given to the relevant historical periods but some preliminary considerations will be offered now. Attention will focus on the expression in literature throughout the centuries of the continued practice of religious diversity – usually in clandestine form – under Roman Catholic rule in the parts of the Iberian Peninsula that in 1143 became Portugal; but also on the concomitant quasi-paranoia that underpinned the attempt, on the part of the status quo, to preserve itself from such contamination.8 This monograph will bring together a range of authors and periods with the aim of investigating the role played in nation formation by an on-going state of clandestine polymorphism (involving a wide spectrum of ethnic, religious, political and gender interests), in the face of sought uniformity. The authors span a period from the eighteenth century to the present, and the chronological setting of the texts ranges from the period of Roman occupation of the Iberian Peninsula in 218 BCE, through the Moorish invasion and its aftermath in 711, the period of the Inquisition from the sixteenth to the ← 6 | 7 → nineteenth centuries, to the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, under the Salazar regime and in its aftermath. Irrespective of chronology, the thread that runs through these authors and informs both their writing and the analysis to be conducted here is that of an oppositional stance towards the political climate and governance of their contemporaneity. In all cases, allegory and apparent historical anachronism become vehicles for the expression of political dissent against statuses quo framed by a system of mutual support between Church and State. It will be my contention that throughout the centuries, a number of literary texts have addressed in more or less covert ways the reality of a social organization which in Portugal, throughout its history, upheld antagonism to and the suppression of any revisionism of established gender or religious conformity. Gender will be the common thread that links other forms of dissent within a system that in different periods variously excluded Pagans of various denominations, Jews and Muslims.

Roman Catholicism was the official state religion in Portugal from the nation’s foundation after secession from Castile in 11439 until the establishment of democracy in 1974. At various points, including in 1870 and 1940 – the latter under the right-wing dictatorship of Salazar’s Estado Novo (1932–1974), the link between Church and State was rendered official through the signing of aforementioned concordats with the Vatican.10 ← 7 | 8 → These, enforced by a variety of monarchs and subsequently heads of state from the eighteenth century to the last quarter of the twentieth, resulted in a national reality largely characterized by the urge towards political and religious consonance which, under the joint rule of Roman Catholicism and either absolutist monarchy or one-party dictatorship, discouraged any form of pluralism, with, as we shall see, a particularly harsh effect on women’s lives and their right to freedom of action and expression.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 344

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788740944

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788740951

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788740968

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034319621

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14737

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (November)

- Keywords

- Religious dissidence Persecution Female non-conformism

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XIV, 343 pp., 1 table, 1 graph