Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

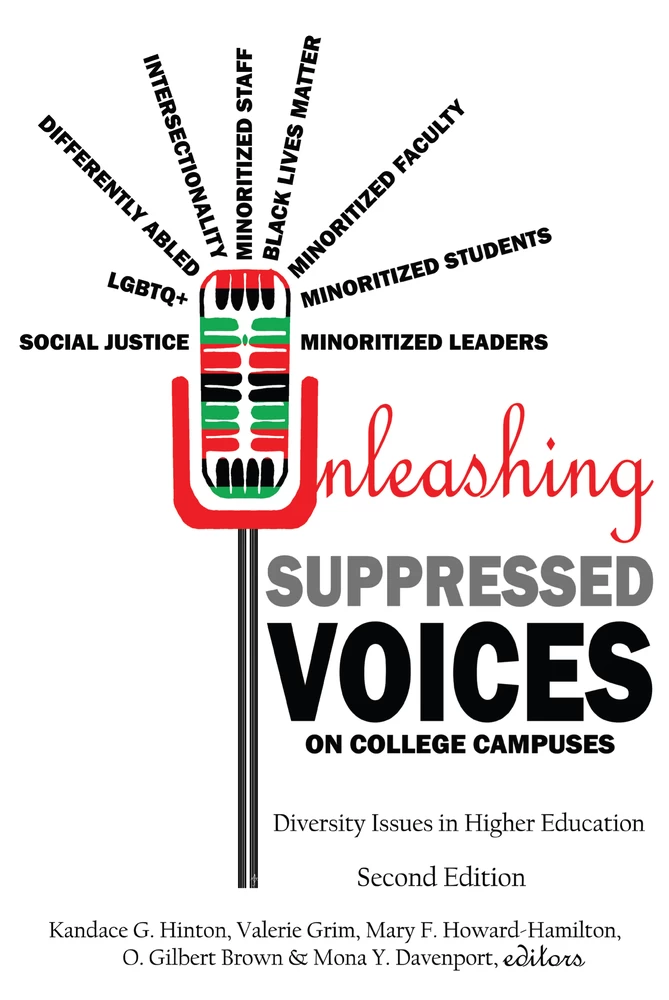

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Part I

- Introduction (Valerie Grim)

- Applying Theory to Practice (Mary F. Howard-Hamilton)

- Using Cases for Teaching and Learning (Kandace Hinton and Valerie Grim)

- Part II Identity, Environment, and Accessibility

- Audism and Hearing Privilege Within Higher Education: A Snapshot into the Lives of Diverse Deaf Communities (Lissa Stapleton and Kathleen Gillon)

- When Conflicting Needs Require Compromise: A Case Study of Gender-Inclusive Restroom Implementation (Janice A. Byrd, Amanda Mollet, Lindsay Jarratt, Cindy Ann Kilgo, Stephen Malvaso and Sherry K. Watt)

- Harmless Joke or Act of Racism? (Jeff Aupperle, Jesse Brown and Kelly Yordy)

- Confrontations with History: Examining the Myths Behind Campus Symbolisms (Mahauganee D. Shaw Bonds and Wilson K. Okello)

- Food Need and Food Assistance in College (Yasmine Dominguez-Whitehead and Valgerdur A. Hardy)

- Accessibility or Inclusivity: A Case Exploring Students with Disabilities (Amy French)

- Part III Student’s Voices and Engagement

- Real Talk: Minoritized Students Get Real About Racism During a Student Affairs Graduate Program Interview Weekend (Aeriel A. Ashlee and David Perez, II)

- Nontradition Goes to College (Andrew Buckle and Laura Glasbrenner)

- Dismissed: A Case of How Doctoral Teaching Assistantships Can Be Used to Enhance Students’ Abilities or Provide a Justifiable Reason for Termination (Amanda J. Muhammad and Chajuana V. Trawick)

- Invisible on Campus: The Case of Undocumented College Students (Berenice Sánchez, Wende’ Ferguson and Lori Patton Davis)

- She’s Not My Brother! (Gary D. Ballinger and Jessica L. Ward)

- Adjusting to the College Setting: The Influence of Support During the College Transition for Minoritized Students (Keeley Copridge)

- To Matriculate or Not to Matriculate: A High Achieving Black Male Student’s Decision to Attend College (Thomas Witherspoon)

- Embracing Peter: Intersectional Tensions Between Race, Social Class, and Sexual Orientation Identity Factors (O. Gilbert Brown)

- Part IV Leadership, Governance, and Faculty

- We Hire Them but Cannot Retain Them: The Impact of the Toxic Environment on Minoritized Staff (Aaron C. Slocum and Azizi J. Arrington-Slocum)

- To Be Young, Gifted, and Tenured: A Black Woman’s Journey to Tenure and Promotion at a PWI (Sydney Freeman, Jr. and Steven Bird)

- We Have to Do Better: Tenure and Promotion for Black Women Faculty (Wende’ Ferguson, Berenice Sánchez and Lori Patton Davis)

- Speak Up or Stay Silent: Facilitating Difficult Dialogues (Brian L. McGowan and Renard John-Finn)

- A Tenured Threat (Haley Atwell, Gabrielle Miller, LeAsha Moore and Amy French)

- It’s Not Magic, It’s Mentoring (Dwuena C. Wyre and Brenda O. Mitchell)

- Part V Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity

- Diversifying the Board of Trustees: Intent Is Important (Amy French)

- Valuing Diversity but Not When It Affects Me (Shawn D. Peoples)

- Community vs Policy: Complicating Administrators Interpretations of Policy and Responsibility (Institutional Decision-Making and Equity) (Natasha N. Croom and Jonathan Webb)

- Black Women “Embodied Text”: Sexual Deviance/(In) Difference Inside the Classroom (Saran Stewart and Chayla Haynes)

- One Size Does Not Fit All: More Inclusive Than Thou (O. Gilbert Brown)

- Contributors

- Index

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Ms. Kelsey Bogard, a doctoral candidate at Indiana State University, for her tireless work assisting us in getting this book to completion. We are thankful for our family members who have constantly stood with us throughout our careers. Thank you to our institutions that provided the space for this work to be conducted and completed.

←xi | xii→

Introduction

valerie grim

Since its inception, higher education has always been an idea that, if developed, could enhance people’s lives and lead to improvement in communities throughout the world. As it evolved from 1636 in colonial America and later in what became the United States of America in 1776, higher education initially was an experience in which only the elite, White and primarily ministers, could engage. Through time, social and political leaders realized that education for the elite was insufficient to transform society and to prepare citizens to be significant contributors to their communities and the larger American society. Eventually during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, more men, especially from working class communities, and due to the establishment of land grant institutions, began to enroll in college, while women of elite backgrounds participated in higher education in the elite liberal arts and private institutions to prepare themselves to be respectful citizens, charitable neighbors, mothers of potentially influential sons, and great wives. At predominantly White universities, Black and poor people’s participation in higher education did not increase significantly until after World War II for men, especially, and after the 1960s for African Americans who protested and integrated predominantly White institutions (PWIs) of higher education. With the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965, the opportunity to have greater presence in higher education at PWIs meant that these kinds of institutions, offering admissions to minoritized populations, would have to consider also the impact of minoritized students’ evolving demands for equality and ←3 | 4→equitable treatment on the White student population. People who were seen as different wanted fair and equitable treatment as human beings in spite of their race, ethnicity, gender, orientation, differently ableness, class, and religion.

To address contemporary issues of equity and inclusion, identity, and accessibility in higher education, for example, this second edition on Unleashing Suppressed Voices utilizes a case study approach to share narratives of lived experiences that provide insights that are useful in understanding how to forge change and transformation regarding race, ethnicity, gender, class, ableness and other encounters in academic communities. The book is divided into five parts. Part I is an introductory section that outlines this text; and it also includes two chapters; one is a chapter concerning theoretical foundations on which premises of this edition is based. The other is a chapter that discusses pedagogical uses of case studies, thereby indicating how to apply theory to practice. The second part of Unleashing examines identity, environment, and issues related to accessibility. In the third part, cases provide experiences that help readers understand the value of students’ voices and engagements as forms of inclusion and equity. Leadership and governance, where faculty are concerned, require input from faculty in order to develop and sustain a culture of equity in higher education, which is discussed in the fourth part. The final section of the book explores issues and experiences some people have encountered working to achieve inclusion, diversity, and equity within their particular areas of employment and engagement in higher education.

Part II: Identity, Environment, and Accessibility

Part II provides an intersectional discussion of the various ways people think about and live identity. This discussion connects identity to space and place, while also indicating that identity for some is the essence of encounters they experience based on others’ reactions to their bodies and what their presence suggests and embodies. For others, identity is shaped by imaginations that otherize them as human beings. The content of cases in Part II, therefore, includes chapters on audism, gender inclusiveness, acts of racism, food needs, the need for various kinds of assistance as well as the call for policies that provide greater inclusivity and belonging in every area of academic life.

Part III: Students’ Voices and Engagement

Similarly in part III, the voices of students are presented in many different forms and in numerous cases to raise questions about the necessity of engagement to ←4 | 5→address new and evolving issues that critically impact the success and achievements of minoritized students on college campuses regarding what appears as progressive thinking, while experiencing situations that reflect retrogressive actions. Within this context and responding to inconsistencies as far as the need for positive and sustained reinforcement of engaged ideas are concerned, engagement is defined as action, ways students work together to confront struggles and differences they encounter. The cases in this part express new ways that students are demanding voice and respect for the ways they attack and redefine racism, discrimination, and invisibility. Part III includes chapters on minoritized students and racism, non-traditional African American students, doctoral teaching assistantship training, issues related to invisibility on campuses, and experiences of first generation college students.

Part IV: Leadership, Governance, and Faculty

Continuously, ideas and best practices concerning leadership, governance, and faculty decision making are in great demand in order to further improve relationships among diverse communities of people in the academy. With the many and varied types of leadership styles and practices of governance, institutions of higher learning have to be committed to collecting data and stories that help leaders understand how to transform existing systems and policies that are failing to produce inclusivity and equitable practices. The cases in Part IV offer new paths and ideas that suggest new management and policy approaches that build confidence among approaches developed to improve inclusiveness in leadership within departments, schools, colleges, provost offices, and offices of the president. Not only do faculty want to be valued, they also desire to be included in decisions; they often like to have a voice in determining evolving policies, actions, and governance approaches that strengthen leadership at every level of the university. In Part IV, cases, such as “We Hire Them But Cannot Retain Them,” “To Be Young, Gifted, and Tenured,” “We Have to Do Better,” “Speak Up or Stay Silent,” “A Tenured Threat Case,” and “It’s Not Magic, It’s Mentoring,” provide appropriate narratives that emphasize a greater need for inclusiveness, shared authority, and leadership.

Part V: Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity

Part V draws attention to the great need to continue pressing for conversations and policies that create greater inclusion, diversity, and equity on college campuses. These cases help us understand - that while inclusion has delivered some ←5 | 6→positive results that have improved diversity in some areas of college and university campus life, especially as it (inclusion) relates to diversifying departments as well as academic, student affairs, and administrative offices - universities are ways away from experiencing success with equity. There is still a great need for gender, racial, disability, orientation, and other forms of equity to become more visible and entrenched in places on college campuses where severe marginalization still prevails. Critical and relevant issues are timely assessed in the body of knowledge presented in cases comprising Part V. They include: “Diversifying the Board of Trustees,” “Valuing Diversity but Not When It Affects Me,” “Community vs. Policy,” “Black Women Embodied Text” and “One Size Does Not Fit All.”

Taken together, each section of this volume, through the collective cases, offers a different perspective on issues and encounters that individuals in higher education experience continuously. Our work, therefore, concerns paying close attention to consistencies that sustain exclusion, to forms of resistance that maintain hegemonic thinking, and to practices and policies that produce stagnation and no real transformation. We also give attention to articulating ways forward that offer new paths to achieving complete diversity and full inclusiveness in the academy.

Applying Theory to Practice

mary f. howard-hamilton

The use of student development, social justice, and organizational theories should be the first step in assessing and identifying the issues that emerge when reading a case. Bell (1997) stated that “practice is always shaped by theory, whether formal or informal, tacit or expressed” (p. 4). Applying theory to practice allows the reader to detect what may be an underlying problem because a more global and empathetic perspective is taken. Theory allows readers to step outside of the frame of reference they operate from on a daily basis and allows them to view a situation from a broader world view. This allows the readers to approach the case from a higher level of cognitive complexity as well as creatively and sensitively provide suggestions for outcomes that could lead to an amicable conclusion to the dilemma.

It is imperative for professionals working in higher education to understand how the organization, environment, and behavior of the person all intersect to create a dynamic climate that can be compatible or clash with others in the institution. McEwen (2003a, pp. 154–155) noted that “it is our responsibility, both professionally and ethically, to know and understand the individuals, groups, and institutions with who we work. One important way to do this is through theory.” Furthermore, Freire (2018) proffered that theory and practice intersect then become the interactive and historical process called praxis. It is the praxis that gives rise to sound case analysis outcomes and interventions.

←7 | 8→Why Use Theory?

There are three reasons why administrators should integrate theory into their daily practices and decision-making processes according to McEwen (2003a, p. 154): 1) it provides a theoretical basis for knowledge, expertise, and practice serves as a foundation for a profession; 2) knowing and understanding theory provides a medium of communication and understanding among student affairs professionals; and 3) theory can serve as a common language within a community of scholars. Student development theory is a framework to inform thinking and understanding of the complexities of human development. Bell (1997) expounds upon the importance of theory stressing that it allows those reading the cases to clearly think about their intentions and how they manifest themselves in actions and outcomes. She also states that theory allows the reader to question old practices and create new techniques or paradigms. Last, theory forces people to learn from the past and stay conscious of how current situations can be viewed in a more imaginative and effective manner.

Clusters of Student Development Theories

There are several clusters of student development theories and they are psychosocial, cognitive structural, typology, and person environment (Patton et al., 2016). Psychosocial development is concerned with the major challenges that impact an individual’s personal and psychological oriented aspects of self and the relationships that exist between the self and society (Hamrick, Evans, & Schuh, 2002). According to Evans et al. (1998), “Psychosocial theorists examine the content of development, the important issues people face as their lives progress, such as how to define themselves, their relationships with others, and what to do with their lives” (p. 32). Primary theory in this cluster is the seven vectors of development (Chickering & Reisser, 1993) and they are: (1) developing competence; (2) managing emotions; (3) moving through autonomy toward interdependence; (4) developing mature interpersonal relationships; (5) establishing identity; (6) developing purpose; and (7) developing integrity.

Cognitive developmental theories attempt to understand the thought processes of individuals and how they construct or make meaning of the experiences in their lives (Evans et al., 1998). The major theoretical influence in this cluster is William Perry’s forms of intellectual and ethical development. He determined that there were nine positions of intellectual development (1) basic duality; (2) multiplicity prelegitimate; (3) multiplicity legitimate but subordinate; (4a) multiplicity ←8 | 9→coordinate; (4b) relativism subordinate; (5) relativism; (6) commitment foreseen; (7–9) evolving commitments (Evans et al., 1998). Typology theory examines how individuals view and relate to their respective environment as well as to the persons within that sphere. The two theories in this cluster used by most higher education administrators are the Holland theory of vocational personalities and environments and the Myers Briggs Personality Inventory. Holland’s six personality types are (1) realistic; (2) investigative; (3) artistic; (4) social; (5) enterprising; and (6) conventional. Myers Briggs “suggests that there are eight preferences arranged along four bipolar dimensions: extraversion-introversion (EI), sensing-intuition (SN), thinking-feeling (TF), and judging-perception (JP)” (Evans et al., 1998, p. 246). The eight preferences can be grouped in a combination of sixteen different types (ISTJ, ENTJ etc.).

Person environment theory examines the student and the environment as well as the interaction of the student with the environment. The formulae for this theory is bf = (p x e) and is often connected with the notion that challenge and support are important factors that should occur within an institutional environment to induce psychosocial and cognitive growth within the individual (Patton et al., 2016).

Cross’ Psychological Nigrescence

While the vectors of development provide one perspective of the case, as reflective students, administrators, faculty in every discipline, as well as consultants the scope must be broadened within the realm of psychosocial understanding to include issues of race and identity development among college students. A widely used theory of identity development is William Cross Psychological Nigrescence. According to Cross (1991), nigrescence refers to the process of “turning Black”. It defines the process of, “accepting and affirming a Black identity in an American context by moving from Black self-hatred to Black self-acceptance” (Vandiver, 2001, p. 166). Originally introduced in the 1970s during the latter portion of the Civil Rights Movement, this five-stage theory has stood the test of time and has since been reexamined and revised to four stages: 1) Pre-encounter is described as low race salience and there is very little connection to one’s ethnicity and culture; 2) Encounter Blacks are faced with a racial crisis which causes considerable intellectual and personal disequilibrium, thus leaving them questioning their allegiance to the dominant culture; 3) Immersion-Emersion involves movement from a Eurocentric frame of reference to one that is African-centered. Within this movement, students deal with their racial discomfort and insecurities about the formation of a new identity, which may entail becoming Pro-black and/or ←9 | 10→anti-white. Pro-blackness may be seen by students immersing themselves in visible aspects of black culture such as the changing of hair, style of dress, and participation in all-Black events and organizations. Anti-white may be seen in students separating themselves from aspects of White culture; 4) Internalization finds Blacks becoming comfortable with their racial identity and culture. There is a commitment to changing the social order by investing time and energy in culturally relevant activities.

4) Internalization The idea of creating a healthy black identity revolves around two major concepts, reference group identity and race salience. Reference group identity, the foundation of nigrescence focuses on the complexity of social groups that individuals use to make sense of themselves as social beings (Vandiver, 2001). Race salience, “refers to the importance or significance of race in a person’s approach to life and is captured across two dimensions: degree of importance and the direction of the valence” (Vandiver, 2001 p. 168). An individual can have, for example, “a high salience for race with a positive (pro-Black) valence or a high salience for race with a negative (anti-Black) valence” (Vandiver, 2001, p. 168).

Privilege, Multicultural Competence, and White Identity Development

McIntosh (1988) wrote a germinal article on privilege in which she defines it as the process of granting the dominant group opportunities that indiscriminately or blatantly acknowledges them systemically, politically, economically, and culturally. The unequal dissemination of these unearned privileges makes it difficult for marginalized or oppressed groups to gain any economic, personal, or cultural momentum in society (Hobgood, 2000; Howard-Hamilton & Frazier, 2005). Moreover, the effects of privilege “are so pervasive that they can be felt between people of color even when no white people are present, as well as between whites even when no people of color are present” (Hobgood, 2000. p. 36). Higher education administrators and faculty should examine their assumptions, biases, and privileges because who we are and what we believe may have a direct impact on how the cases in this text will be evaluated, deliberated, and reviewed. Moreover, when a recommendation is made regarding the outcome of how the individuals or organization in the case should be treated, the sanction could be too harsh or too lenient depending upon the personal world view of the reader. McEwen (2003a) insists that

Student affairs professionals need to ask questions of themselves, such as Who am I, as an able-bodied, middle-class, educated White woman? or a second-generation bisexual Asian man? or an African American woman? or a person with any other combination of characteristics? Such self-reflection will help you discover and ←10 | 11→understand those frameworks you use in both the consideration and the application of theory. (p. 174)

Reading and memorizing theoretical stages and applying them randomly without personal reflection and purposeful planning could leave the administrator and student disappointed and bitter because a sensitive and thoughtful plan of action was not taken. Assumptions about a person’s race, class, or gender is the mindset of a privileged individual. Multiculturally competent faculty, administrators, and staff would engage in personal reflection in addition to understanding and learning about other cultures, recognizing and deconstructing white culture, recognizing the legitimacy of other cultures and developing a multicultural outlook (Ortiz & Rhoads, 2000). Therefore, understanding and embracing the levels of white identity development becomes critical because it is foundation and framework for working with diverse groups. Furthermore, “identity development represents a qualitative enhancement of the self in terms of complexity and integration” (McEwen, 2003b, p. 205). The White Identity Development Model is a prime example of how one’s identity becomes more complex when attempting to inculcate diversity issues with previous socialized perceptions of race.

The White Identity Development (WID) Model (Hardiman, 2001) was designed to explain “how Whites came to terms with their Whiteness with respect to racism and race privilege” (p. 111). The five stages of the WID are (1) No Social Consciousness of Race or Naiveté, (2) Acceptance, (3) Resistance, (4) Redefinition, and (5) Internalization.

The first stage is a naïve period in which whites have no understanding or recognition of other cultures and races. They are also unaware of how status and value is ascribed to one race over another. Acceptance, stage two, occurs when Whites recognize that “it is impossible in this society to escape racist socialization in some form because of its pervasive, systemic, and interlocking nature” (Hardiman, 2001, p. 111). Whites have an understanding that privilege exists and accept an understanding that they are perceived as superior to people of color. This is not a conscious choice by white people but oftentimes is an unconscious choice and a “by-product of living within and being impacted by the institutional and cultural racism which surrounds us” (Hardiman, 2001, p. 111).

The racist programming that has occurred unconsciously and consciously is questioned at the third stage called resistance. This is an action-oriented stage wherein Whites can become liberators for social justice and equal opportunity by fighting to ameliorate racism and other forms of oppression. This leads to a redefinition and clarification of why she/he is interested in working against racism, and begins to embrace one’s whiteness rather than deny or denounce it. The ←11 | 12→new white identity is internalized in the fifth stage thus raising their level of racial consciousness and integrating it into every aspect of their persona.

Social Justice Models

Social justice is a term used to describe a societal process in which there is a shared vision for the equitable distribution of resources and there is physical and psychological safety for all people (Bell, 1997). The individuals in a social justice system are self-determining and empowered. They “have a sense of their own agency as well as a sense of social responsibility toward and with others and the society as a whole” (Bell, 1997, p. 1).

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 332

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433186035

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433186042

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433186059

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433186028

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18195

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (April)

- Keywords

- USA Hochschule Aufsatzsammlung Diversity Affirmative Action Academic Affair Racial Diversity Leadership

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2021. XIV, 332 pp., 2 b/w ill.