Interprofessional interactions at the hospital

Nurses’ requests and reports of problems in calls with physicians

Summary

By adopting a conversation analytic approach, the author identifies the formats through which nurses implement requests to physicians. She distinguishes between requests that contain an explicit formulation of a candidate course of action (e.g. Can you do X), and less transparent formats, such as reports of problems. The latter consist of presenting a series of facts that convey the existence of a situation portrayed as problematic and making relevant the physician’s intervention. To secure the interventionable character of the report, nurses refer to facts remediable only by a medical authority, such as deficiencies contingent to the provision of care or a patient’s medical status.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Research framework

- Setting

- Data

- Audio-recordings

- Ethnographic observations

- Analytical aims

- Chapter I. Hospital interaction between nurses and physicians: a literature review

- 1. Forms of interprofessional communication at the hospital

- 1.1. Scheduled and unscheduled occasions of interaction

- 1.2. Face-to-face and remote communication

- 2. Changes and challenges to nurses’ professional “jurisdiction”

- 2.1. From a traditional model of nursing to a “rôle propre infirmier”

- 2.2. The case of newly employed nurses

- 3. Nurse-physician verbal interaction

- 3.1. Nurses’ and physicians’ attitudes to their communication and collaboration

- 3.2. Verbal exchanges between nurses and physicians

- Conclusion

- Chapter II. Conversation Analysis: an approach to medical interaction and requests

- 1. Conversation Analysis: basic concepts

- 2. Interaction in institutional and medical settings

- 2.1. Interaction between patient and health professional

- 2.2. Interaction between health professionals

- 3. The sequential organization of requests

- 3.1. The organization of requests in adjacency pairs

- 3.2. Preference organization of requests

- 3.3. Requests as “double-barreled” first pair parts

- 4. Request format and speaker display of stance

- 4.1. Claims of entitlement and acknowledgement of contingencies

- 4.2. Epistemic position

- 4.3. Deontic authority

- 4.4. Distribution of benefits

- 5. From “overt” to “less-overt” request formats

- 5.1. Reports of trouble in calls to emergency assistance

- 5.2. Problem descriptions in service calls and calls to helplines

- 5.3. Patients’ problem presentations in encounters with physicians

- Conclusion

- Chapter III. An overview of nurse-physician calls within a Surgery Department

- 1. Nurse competencies in the Swiss training system

- 2. Ethnographic observations of an ad-hoc activity

- 2.1. Organization of nurse and physician activities

- 2.2. The telephone landline in a nurse station

- 3. Number of calls and other quantitative features of the calls recorded

- 4. Calls, connections, conversations, and reasons for the call

- 5. Physician interventions and courses of action

- 5.1. Nurse engagement in a future activity

- 5.2. Physician engagement in a future activity

- 5.3. Nothing needs to be done

- Conclusion

- Chapter IV. The overall structural organization of nurse calls to physicians

- 1. The opening sequence

- 1.1. Summons-answer sequences

- 1.2. Identification-recognition sequences

- 1.3. Greeting sequences

- 2. Transitioning from the opening to the reason for the call

- 2.1. Apologies

- 2.2. Introductory formulas

- 2.3. Pre-requests

- 3. Making and dealing with a request as a reason for the call

- 3.1. Requests made by nurses for physician’s intervention

- 3.1.1 Inquiries regarding the physician’s ability

- 3.1.2 Inquiries regarding the physician’s volition

- 3.1.3 Relayed requests

- 3.1.4 Stating something that needs to be done

- 3.1.5 Reports of problematic facts

- 3.2. Physician responses to requests

- 3.2.1 Responses granting the request

- 3.2.2 Responses not granting the request

- 4. Post-expansions and terminal exchanges

- 4.1. Acceptance tokens

- 4.2. Repeats

- 4.3. Elaborations

- 4.4. Interlocked terminal exchanges

- Conclusion

- Chapter V. Reports of problems

- 1. Turn design of problem reports

- 2. Practices for producing reports

- 2.1. Reports of actionable deficiencies

- 2.2. Reports of patient-centered problems

- 2.3. Displaying the origin of the observation

- 3. Physician responses to reports of problems

- 3.1. Designating a course of action

- 3.2. Deciding that nothing must be done

- Conclusion

- Chapter VI. Nurses pursuing an intervention in cases of physician disalignment and disaffiliation to reports

- 1. Dispreference and the pursuit of preferred uptake/response in Conversation Analysis

- 1.1. Recipient disalignment and disaffiliation

- 1.2. Pursuing a(nother) response after the recipient’s disalignment or disaffiliation

- 2. Nurses dealing with physician’s alignment and affiliation to a report

- 3. Nurses dealing with physician’s disalignment to a report

- 3.1. Dealing with lack of uptake after the report

- 3.2. Dealing with physicians that don’t treat the report as implementing requests

- 4. Nurses dealing with physician’s disaffiliation to a report

- 4.1. Pursuing the problematic character of the fact reported

- 4.2. Pursuing the actionable character of the report

- Conclusion

- Chapter VII. Nurses’ participation in medical decision-making

- 1. Intercepting errors

- 2. Engaging in treatment recommendation

- 2.1. Initial requests with explicit formulations of medical courses of action

- 2.2. Proposing medical courses of action alternative to the physician’s decision

- 3. Nurses acquiring clinical knowledge regarding decision-making

- Conclusion

- Conclusion

- Medical intra-institutional and interprofessional interaction

- Overall structural organization of an interprofessional activity

- Sequence organization and turn design of reports as implementing requests

- Entitlement and deontic dimensions in the production of requests

- Practical contribution of the findings

- Methodological and analytical limitations

- Future perspectives

- References

- Appendix 1. Transcript symbols

- Appendix 2. Pseudonyms, abbreviations, and professional positions of NTH–130 interlocutors

- Appendix 3. Medical terms and jargon in transcripts

- Index

- Series index

The publication of this book was funded by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, the Centenary Fund of the University of Fribourg, and the Lausanne University Hospital Foundation.

The research and results presented here are based on my doctoral dissertation, undertaken at the University of Fribourg. I express my sincerest appreciation to Professor Esther González-Martínez, my supervisor, for encouraging me to develop as a research scientist, and Professor John Heritage, whose comments, advice, and availability during my visiting semester at UCLA have been priceless. I am equally thankful to the Swiss National Science Foundation for the resources allocated during my doctoral studies and to the Hôpital Neuchâtelois for allowing access to such unique data.

I am grateful to my family and close ones for all their support throughout life and diverse projects – I mention in particular my parents, Catalina Schoch, Marine Vidaud, Johanna Lindell, Fabien Dubosson, and Amanda McArthur, whose proofreading and comments have been inestimable for my work. ← 15 | 16 →

In this book I present the outline and outcomes of research accomplished as part of my doctoral studies at the Faculty of Arts and Humanities, University of Fribourg, Switzerland (December 2012 to January 2016). The findings are based on data collected during the project: “New on the job: Relevance-making and assessment practices of interactional competences in young nurses’ hospital telephone calls” (Project leader: Prof. Esther González-Martínez). “New on the job” was launched in January 2012 and was concluded in December 2015. The project was part of a Sinergia project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, titled “Interactional competences in institutional practices: Young people between school and the workplace” (grant no. 136291). The project was meant to analyze newly employed nurses’ interactional competences as deployed during telephone encounters with other hospital personnel. Using a conversation analytic approach, my research focuses on the activity of telephone care coordination during nurses’ conversations with physicians from the same units.

The project was launched in collaboration with the Haute Ecole Arc Santé, a Nursing School within the University of Applied Sciences–Western Switzerland (HES-SO), and in partnership with the Hôpital Neuchâtelois, a public hospital of the canton of Neuchâtel (the site of our data collection), situated in the French-speaking part of Switzerland. The Hôpital Neuchâtelois is composed of seven regional hospitals. The recordings took place at one of these regional hospitals (hereafter mentioned as “the hospital”) situated in one of the biggest cities of the canton Neuchâtel. This hospital is a mid-sized acute care facility which sees a great number of patients.

In the framework of the “New on the job” project the research team collected 374 audio-recorded telephone calls, made and received on/from a landline over the course of six months between three newly employed nurses within the Surgery Department—Leandra1 (hereafter ← 19 | 20 → Lea), Amaryse (hereafter May), and Timée (hereafter Tim) —and other interlocutors from 14 hospital departments. All the participants were informed orally and in written of the research project and that recordings would be made. They were given the opportunity to freely opt out of the study if they so wished and accepted to be recorded. A pre-recorded voice message reminded callers that the calls were being recorded for research purposes. The research team anonymized all personal information related to the telephone interlocutors and any persons referred to during the calls.

Data also include ethnographic field notes from observations of nurses’ and physicians’ daily interactions and work routines within the Surgery Department care units recorded, and of other interlocutors with whom the nurses spoke frequently over the telephone. Conversation Analysis (CA) was used for the analysis of the recorded phone calls.

Previously published studies on this data investigate the use of the telephone as a device for care coordination at the hospital (Vaucher & González-Martínez 2014, 2015a, b) and contribute conversation analytic descriptions of nurses’ calls with different members of the personnel within the hospital (González-Martínez & Petitjean 2016) such as an intensive care nurse (Petitjean et al. 2015), dieticians (González-Martínez et al. 2016a), porters (Sterie & González-Martínez 2017), and physicians (Sterie 2015, Sterie & González-Martínez 2017).

The research presented here focuses on 130 conversations between nurses and physicians recorded for the project, in which nurses request the physician’s intervention through different conversational actions (e.g. overt requests versus reports of problems) delivered in various grammatical formats (e.g. declaratives versus interrogatives).

During the time the recordings were made, the three nurses who made and received the calls—Lea, May, and Tim—were employed in units 4 (Lea and May) and 8 (Tim) of the hospital’s Surgery Department, which deals with ambulatory and hospitalized patients. Units in this ← 20 | 21 → department care host patients up to two days before surgery, and for no longer than two weeks after the surgery; sometimes, the patient’s recovery may continue within another department or hospital. The primary surgical specializations in the department are visceral and traumatology.

Units 2, 4, and 8 of the Surgery Department are situated on the third floor of the hospital; they comprise nurses’ and physicians’ offices and patients’ rooms. Unit 2 is closed during the weekend, while units 4 and 8 are functional all week. Patients admitted in the latter two are awaiting surgery or have just had surgery and are recovering after having been transferred from the recovery room or the intensive care.

Lea, May, and Tim are Swiss Francophone, and were in their early twenties at the time of the recordings and fieldwork. They had received their Bachelor degrees in Nursing Studies from the same HES-SO. When the recordings for the “New on the job” project started, they were within the first year of their first employment in a medical facility, not counting previous mandatory internships and student jobs. As novice nurses they had spent their first three months employed at the hospital shadowing more experienced nurses and attending an integration class.

The 123 correspondents whose calls could be recorded belonged to 19 different departments: Bed management, Care services, Emergencies, Intensive care, Laboratory, Medical imaging, Occupational therapy, Outpatient clinic, Nutrition, Pharmacy, Physiotherapy, Porter services, Reception, Recovery room, Social and liaison service, Surgery, Kitchen, Technical service, and Security. Among these, most calls were exchanged with physicians from the Surgery Department. Within the Surgery Department, Lea, May, and Tim exchanged calls with six categories of physicians (AMINE 2006)2. The médecins assistants, hereafter “residents”3, are on their first work experience after having received their Federal Medical Diploma and are preparing for their postdoctoral degree. In Neuchâtel, residents’ employment takes three years, and their role is to assist other physicians. The chefs de clinique ← 21 | 22 → adjoints, hereafter “fellows”, have received their postdoctoral degree and have two or more years of practice. The next position is that of chefs de clinique, hereafter “attendings”, who have obtained a specialization diploma recognized by the Federation of Swiss Physicians. The médecins adjoints, hereafter “associate physicians”, are specialized physicians titular of a doctoral diploma, and assist the head physicians. The médecins chefs, hereafter “unit head physicians”, have several years of experience and are specialized in a surgical domain; they are responsible for the management of a service or department and are in charge of teaching and research (CSFO 2012)4. Throughout this book the group as a whole shall be referred to as physicians (although arguably the residents are still in training).

Units 4 and 8 each have designated nurses, a “unit head nurse” (infirmier chef d’unité), a unit head physician, an associated physician, a variable number of attendings and fellows, one traumatology resident (sometimes shared between the two units), and two residents for visceral surgery, each assigned to a particular area of the unit (the North or the South Hall). Supervision within the Surgery Department is conducted by the “Department head physician” (médecin chef de department) and the “Department head nurse” (infirmier chef de département).

Recorded data consists of calls made to and from the landline telephones in units 4 and 8, involving either Lea, May or Tim. The calls were recorded over a period of 6 months between 2012 and 2013 (a total of 174 consecutive days).

The recording was made by Swisscom, the hospital’s telephone service provider. Swisscom installed a server, “Marathon Evolution ← 22 | 23 → Version 10”, on the hospital central telephone line, and rendered recorded data accessible to members of the research team from a computer situated within the hospital’s Technical Service. On this computer, the calls were downloadable in mp3 format through the program PowerPlay. The program also made available a downloadable Excel file containing information about the calls, such as day of the week, start and end time, duration of the call, direction of the call (outgoing or incoming), type of device (landline or mobile), and interlocutor and service identity (according to pre-established codes). The server recorded all calls between the 123 correspondents selected by the hospital and agreeing to participate in the study, which were identified by 155 numbers—111 mobiles and 44 landlines—and the landlines situated in units 4 and 8. The calls and the information were collected once per week by a member of the research team.

The calls to and from the landlines in the nurses’ stations in units 4 and 8 were recorded and collected as part of the “New on the job” collection, which is comprised of 9,931 calls. The landline could be used or answered by anyone in the nurses’ station, but the project restricted analyzable conversations to those issued from calls made or received by Lea, May, and Tim. The calls recorded were listened to by the team members to select only calls made or received by one of the three nurses, which thus formed the NTH–3 corpus, comprised of 374 calls. This selection was possible due to the fact that nurses always identify themselves when talking on the landline. Furthermore, I focus only on calls with physicians, which comprise the NTH–130 sub-corpus, consisting of the 130 calls used for this study. I was able to sort calls according to interlocutor using the aforementioned Excel file.

All personal information in the NTH–3 corpus was anonymized in the audio files with the use of specialized software (Audacity), removing personal and institutional names, unit/service names, dates, addresses, telephone numbers, and city names. The anonymization allowed for calls to be replayed for larger audiences without disclosing details regarding the interlocutors, the hospital or the patients. The calls were then transcribed using the Jeffersonian (Jefferson 2004) system (C.f. Appendix 1), using Audacity and Praat. This software allowed the measuring of the exact duration of lapses of silence or of overlapping talk. ← 23 | 24 →

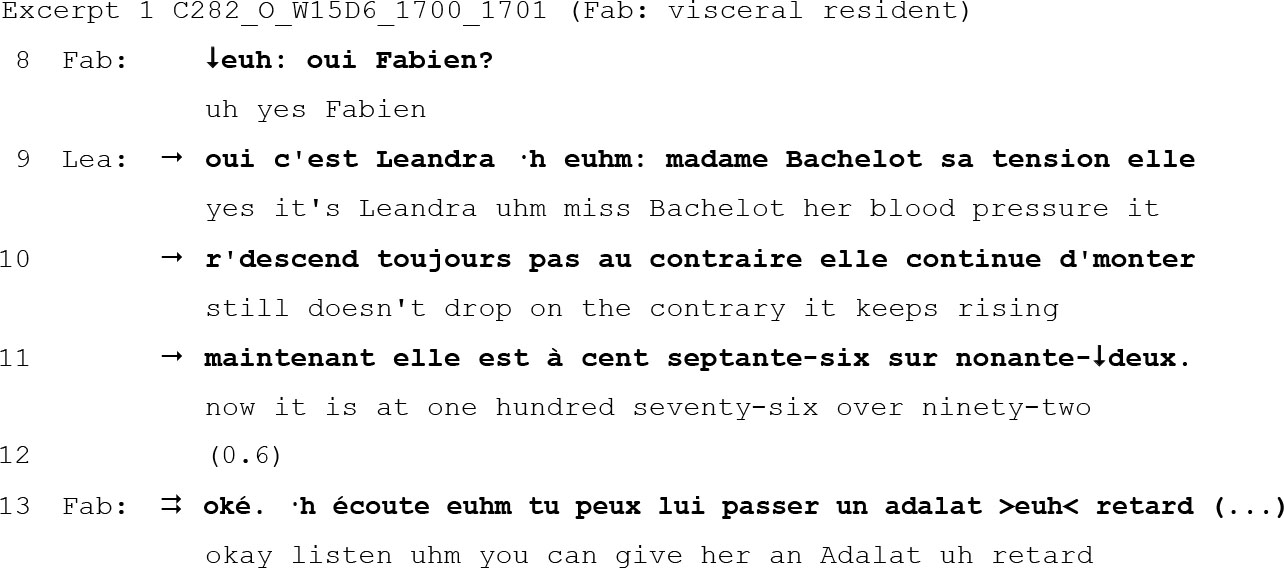

Below is an example of an excerpt of a recorded conversation between a nurse, Lea, and a resident physician, Fab.

The number of the Excerpt (here, Excerpt 1) positions it within the chapter. The conversation is then referred to, in the header, by its technical identification. Above, C282_O1_W15D6_1700_1701 reads Conversation 282 (out of the NTH–3 database), Outgoing call (made by the nurse), Week 15 (from the start of the recording), Day 6 (Saturday), made at 17:00 and ending at 17:01. In the transcripts, each interlocutor’s pseudonym is shortened to three letters: in Excerpt 1, Leandra (Lea) is the nurse and Fabien (Fab) is the physician. In the header of the excerpt I have included, in parenthesis, the institutional identity of the nurse’s interlocutor and his specialization5.

Initially I was unfamiliar with French medical terms and abbreviations. For reference regarding medication I consulted the online Swiss compendium of medicine. For reference regarding symptoms, diagnostics, names of tests, etc. — a jargon which is often specific to each hospital— I consulted the nurses working in units 4 and 86.

I translated all calls made between the three nurses and physicians to English; all excerpts contain the original version (in bold) and immediately after, its translation. Often I was faced with a choice between a translation that reflects “hospital talk” but isn’t respectful of the lexical choice and turn design employed by the participants in the ← 24 | 25 → conversation. In addition, certain French terms and expressions don’t have a correspondent in English. When the phenomenon under analysis depends heavily on lexical choice and turn design, I employ a three-line transcript (first line French, second line literal English translation, third line routine English translation).

The research was undertaken with the overarching objective of analyzing finely-grained features accomplished in interaction by relying on naturally bounded data. The Jeffersonian system allows for a detailed transcription that makes easily available phenomena and patterns in the conversation. In Excerpt 1, for example, such detail allows attention to be drawn to the point of interest in my research—the production of a report of problems by the nurse (marked by the single arrows)—and to how it is understood and dealt with by the physician (marked by the double arrow). In order to study the particular phenomenon of how nurses formulate their requests to physicians, I deploy the approach of CA, a micro-analytic study of social interaction as talk-in-interaction through the use of audio-recorded data (Sacks et al. 1974).

Details

- Pages

- 390

- Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034327350

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034327367

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034327374

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034327343

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11717

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (April)

- Keywords

- conversation analysis reports of problems requests telephone interaction interprofessional interaction nurses care coordination at distance hospital physicians

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2017. 390 pp., 2 coloured fig., 6 b/w fig., 2 tables