Richard III as a Romantic Icon

Textual, Cultural and Theatrical Appropriations

Summary

(Keir Elam, University of Bologna)

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

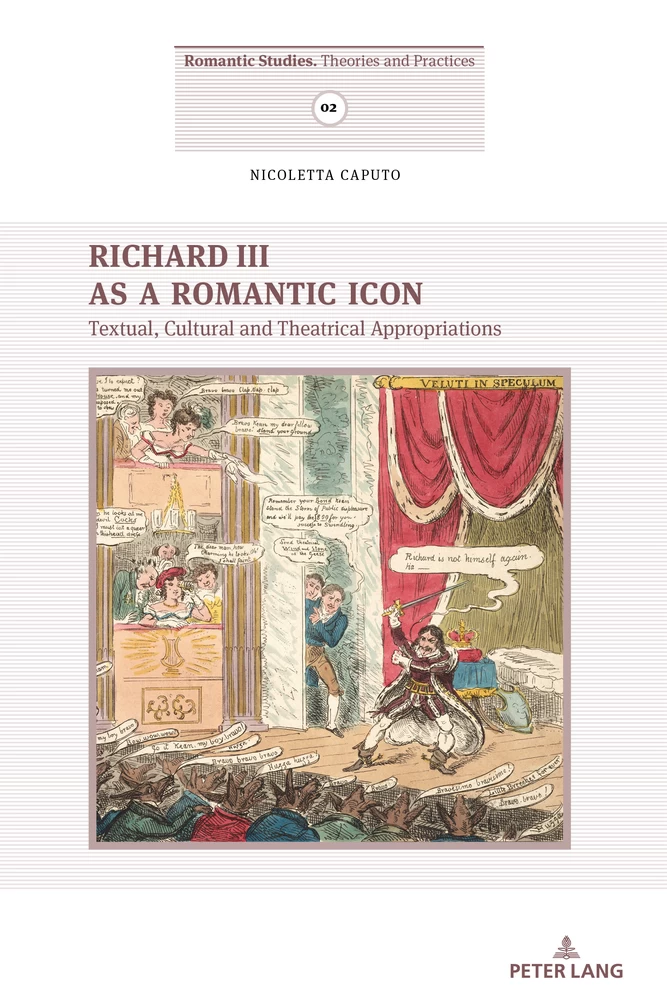

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Richard III as a “Romantic” Icon

- Part I: The “True” Richard III

- Chapter 1: Revising the Tudor Myth in the Eighteenth Century

- Chapter 2: Richard’s Reputation in Romantic Times

- Chapter 3: A “Romantic” Richard

- Part II: King Richard III on the Page

- Chapter 4: Eighteenth-Century Character Criticism

- Chapter 5: The Romantic-Period Critics

- Chapter 6: Two Unhappy Stage Adaptations

- Part III: King Richard III on the Stage

- Chapter 7: A Hybrid Richard

- Chapter 8: The “Ogreish” Cooke

- Chapter 9: The “Harlequin” Kean

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index of Names

The research that has resulted in this book took shape during several periods at the Folger Shakespeare Library, first as visiting scholar and then as Folger Shakespeare Library fellow. Thus, my opening thanks are due to the Folger staff for providing me with such a precious opportunity for research, and for proving invariably collaborative and helpful, not only during my periods of residence there but also when I was in Italy.

My gratitude also goes to the staff and the members of the Inter-university Centre for the Study of Romanticism (CISR) of the University of Bologna, directed by Lilla Maria Crisafulli. The numerous and extraordinarily stimulating international conferences, lectures and seminars the Centre has organized over the years made a sixteenth-century scholar like me irremediably fall in love with the Romantic period. I also wish to thank the colleagues of the English Studies Section of the University of Pisa, who have created a serene and productive environment to conduct research and explore ideas. Among them, I am particularly obliged to Carla Dente, whose advice has always proved helpful.

I am enormously indebted to the friends and colleagues who have been generous with their time and attention and have carefully read, either in whole or in part, the manuscript of this book, providing me with competent, perceptive, and unvaryingly valuable suggestions and comments. These are, in order of appearance in the enterprise: William Dodd, Kent Cartwright, Fernando Cioni and Keir Elam. I am very grateful to the editors, Serena Baiesi and Lilla Maria Crisafulli, for including my book in their series “Romantic Studies. Theories and Practices.”

Earlier versions of Chapter 6 and Chapter 8 were published in, respectively, Theatre Survey 52, no. 2 (November 2011), and Textus 24, no. 1 (January–April 2011). Part of Chapter 7 appeared in Offstage and Onstage (Pisa: ETS, 2015). I am thankful to the editors and publishers concerned for kindly granting me permission to reprint material here. I also deem it important to acknowledge the courtesy and generosity of the museums and libraries that have provided the images included in this volume. ← 9 | 10 →

Finally, this book would not have seen the light of day without the loving and unfaltering support of my parents, my husband Michele, and my daughters Giulia and Alice: I want to express my immense gratitude to them for their encouragement and their patience during the many years taken for the completion of this volume.

Introduction: Richard III as a “Romantic” Icon

This book is an investigation into a particular aspect of the Romantic era’s so-called bardolatry, namely the nature and significance of Richard III during this period as both a historical figure and a subject for literary and theatrical representation. While many important critical studies on the appropriation of Shakespeare and on Romantic theater and performance have been written,1 monographs on the appropriation of a specific play in a specific historical period are virtually nonexistent. The starting point of this research was the use and the reuse that each generation has made of William Shakespeare who, in the second half of the eighteenth century, was enshrined as the unrivalled national poet and the embodiment of “Englishness.”2 However, the focus of this book ← 11 | 12 → is not only the reception of King Richard III in Romantic times but also Richard III as a cultural object. Theater obviously occupies a crucial place, but literature, history, criticism, politics and society in general are equally significant. Richard III exerted an almost inexhaustible fascination over the Romantics, and he is found to a surprising degree at the center of literary, theatrical, ideological, and ethical debates over a period of several decades. That could be, in part, because of the conflicting ethical response he aroused, in an age when morally dubious figures (such as George Gordon, Lord Byron) were highly fashionable. The present study intends to highlight the coalescence of discourses related to the figure of Richard III that emerged in the last decades of the eighteenth century, investigate the Romantics’ morbid fascination with this character in its various manifestations, and explore what can be considered a true Romantic-period myth from a variety of points of view.3

In the “Romantic” years, Richard III, like Shakespeare himself, became “a controversial piece of cultural property.”4 As will become evident in this study, Richard’s multifariousness as a dramatic and ← 12 | 13 → cultural figure mirrored the age, and the multiplicity of Romantic- period Richards were strictly connected with the cultural and ideological multiplicity of the Romantic era itself. In addition, the ductile image of Richard often played a part in the process of self-definition of writers and intellectuals. Exemplary from this point of view is the affinity that Byron—who was identified as the head of the “Satanic school” of poetry by the poet laureate Robert Southey5—felt with Shakespeare’s arch-villain on a personal level, and the impact it had on his works. Or, in the last decades of the eighteenth century, the various attempts on the part of the so-called sentimental critics to humanize (and domesticate) a disturbingly vicious character like Richard III. Recurrently, Richard became a site for debating crucial issues of the times. For instance, siding with him gave his admirers—namely William Hazlitt and Lord Byron—the opportunity to develop and express their ideas of heroism. On all such occasions, the politics of the competing Richards—i.e. the different approaches to the historical, dramatic and theatrical figure—really seem to enact different notions of individual and national identity.

Recent scholarship has emphasized how the cultural was political in the Romantic period, and how, repeatedly, heated debates surrounding key cultural figures uncovered arenas of socio-political conflict.6 ← 13 | 14 → Aesthetic divides could mirror political divides. However, while the ideological import of the Romantic-period dispute over Milton’s Satan and Napoleon has been widely explored and discussed,7 the controversy surrounding Richard III and his theatrical interpreters, which was equally ideologically pregnant, has been totally ignored. The politics of the “rival Richards” are extremely interesting, and the divide between pro-Richard and anti-Richard intellectuals mirrors the responses to Satan and Napoleon. The three figures were linked in literary works and in the major thinkers’ comments on the political and cultural situation of the time, sometimes explicitly and sometimes only implicitly. Greatness split from morality was what critics—chiefly hostile ones—generally recognized in Satan, Napoleon, and Richard III alike.

In dramatic criticism, William Richardson was the first who, in seeing admiration rather than pity (as other “sentimental” critics did) as a response to the character, made a possible connection with Satan evident. Occasionally, such a connection merged with a (quite problematic) engagement with another powerful “Romantic” myth: Prometheus. The contest over Satan and Napoleon parallels the contest over Richard III and Edmund Kean, his most acclaimed performer on the stage in the period. Like Satan and Napoleon, Richard III too became a site of dispute over what people deemed important in the field of morality and heroism at a time of great political turmoil. Romantic-period writers and critics constructed and appropriated different Richards to engage more effectively in the complex reality surrounding them, and these competing cultural creations mirrored different ideological positions.

They similarly constructed and appropriated Edmund Kean, an actor who, as Barbara Hodgdon rightly argues, “in a sense, […] was their creation, their commodity.”8 The discussions about Richard III and Kean betray the same political context that characterizes the competing assessments of Satan and Napoleon, with admiring liberal and ← 14 | 15 → radical writers and critics,9 and skeptical or disapproving conservatives. Like Richard III, Kean too became, for liberal and radical writers, a vehicle to express their views on culture, society, and politics. Jonathan Mulrooney, while commenting on the desire John Keats emphatically expressed of being in the “low company” of Kean, instead of dining with respectable “members of the merchant class who aspired to cultural legitimacy through literary pursuits,” rightly notes that the poet’s “explicit alliance” with the actor was a veritable

… identification with the new modes of cultural experience Kean embodied on the early nineteenth-century London stage. […] Kean played a crucial role in shaping both Keats’s attitudes towards his own social rank and his ideas about the changing nature of cultural experience. Educated to an understanding of Kean by Hazlitt’s theatrical criticism, Keats’s attention to the actor in letters and theatrical reviews in late 1817 and early 1818 coincided with and […] occasioned his thoroughgoing revision of the poet’s role as a cultural intermediary for readers.10

Actually, Kean’s “revolutionary” acting and his rendering of Richard III were appropriated by writers from different party affiliations to serve both their aesthetic and their political ideologies, and the actor himself, with his transgressive social behavior, was made into a highly disputed—and highly contradictory—symbol.

Details

- Pages

- 270

- Year

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034329958

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034329965

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034329972

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034329989

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14205

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (December)

- Keywords

- Romanticism Shakespeare Cultural appropriation Theatre and Drama studies Early Modern studies British cultural studies

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018. 270 pp., 15 fig. col., 1 fig. b/w