Die Zauberflöte, Sources - contexte - représentations

Douze études réunies par Henri Vanhulst

Résumé

David Buch démontre que Mozart n’est pas intervenu dans l’élaboration et la rédaction du livret qui est dû au seul Schikaneder. Michael Lorenz fait l’historique du Theater auf der Wieden et détaille grâce à des actes de baptême et autres documents d’archives la nature des relations entre les époux Schikaneder et les membres de la troupe. Jean Gribenski dresse le bilan des premières éditions parisiennes tant de La Flûte enchantée que des Mystères d’Isis. Herbert Schneider et Rainer Schmusch analysent les particularités des traductions françaises et italiennes du livret. Pour ce qui est de Bruxelles avant 1815, Henri Vanhulst examine les traces de la présence du Singspiel à l’aide des catalogues et annonces des marchands de musique et des programmes des sociétés de concert. Alexandra Gelhay, Roland Van der Hoeven, Frédéric Lemmers, Serge Algoet et Valérie Dufour en collaboration avec Laurence Wuidar étudient les étapes marquantes des représentations du Singspiel au théâtre royal de la Monnaie de 1829 à 2005. Trollflöjten, le film réalisé en 1975 par Ingmar Bergman, inspire à Dominique Nasta une réflexion sur les conceptions artistiques du cinéaste.

L’ouvrage réunit douze études, dont deux en anglais et autant en allemand.

Extrait

Table des matières

- Couverture

- Titre

- Copyright

- Sur l’auteur

- À propos du livre

- Pour référencer cet eBook

- Table des matières

- Préface (Henri Vanhulst)

- Sources et contexte

- Die Zauberflöte from Libretto to Score (David J. Buch)

- New Archival Documentation on the Theater auf der Wieden and Emanuel Schikaneder (Michael Lorenz)

- De La Flûte enchantée aux Mystères d’Isis (Jean Gribenski)

- Traductions du livret

- Die Zauberflöte in der anonymen italienischen und frühen französischen Übersetzungen (Herbert Schneider)

- La Flûte enchantée in Frankreich zwischen 1865 und 1914 (Rainer Schmusch)

- Diffusion et représentations à Bruxelles

- La diffusion de Die Zauberflöte à Bruxelles sous le régime français (Henri Vanhulst)

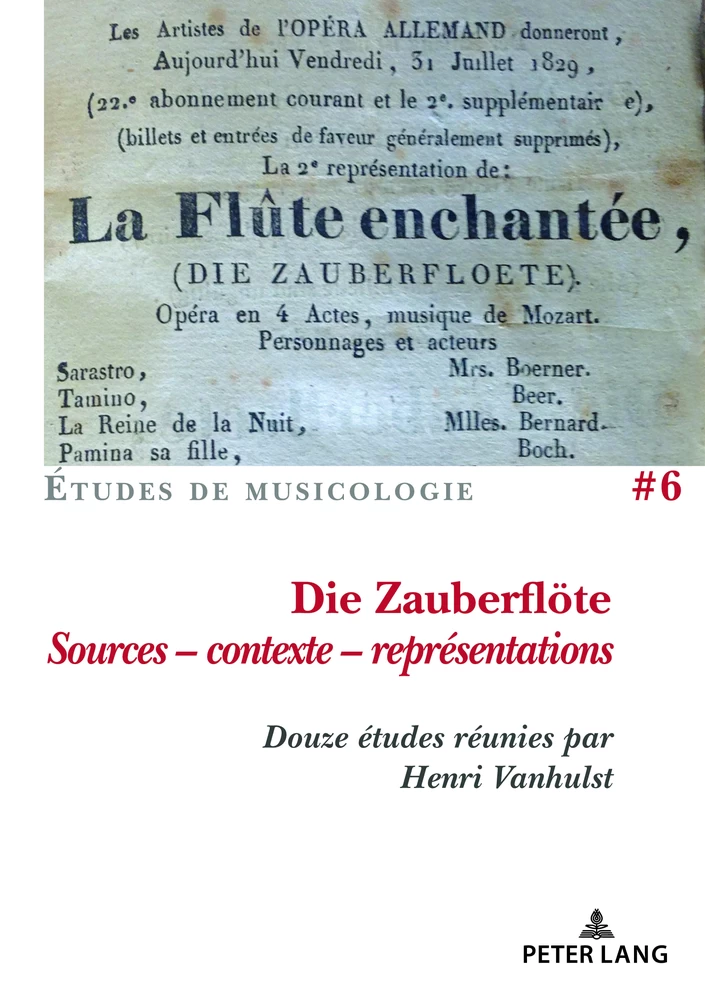

- La première représentation de Die Zauberflöte à Bruxelles (1829) (Alexandra Gelhay)

- Entre enchantements et désenchantements (Roland Van der Hoeven)

- La Flûte enchantée et le théâtre royal de la Monnaie dans l’entre-deux-guerres (Frédéric Lemmers)

- Die Zauberflöte mis en scène par Karl-Ernst Herrmann à la Monnaie (1991) (Serge Algoet)

- Die Zauberflöte en noir et blanc au royaume de William Kentridge (Valérie Dufour / Laurence Wuidar)

- Die zauberflöte et le septième art

- Die Zauberflöte vue par Ingmar Bergman ou l’invention collective (Dominique Nasta)

- Présentation des auteurs

- Index

- Titres de la collection

La réorganisation de l’enseignement supérieur en Communauté française de Belgique a conduit à une collaboration renforcée entre les universités et les établissements organisant une formation de type long non universitaire. Le Pôle universitaire européen Bruxelles – Wallonie en est l’un des résultats ; il réunit autour de l’Université libre de Bruxelles différentes institutions dont plusieurs écoles supérieures d’art de la capitale. Afin de marquer le début de cette collaboration, l’Académie royale des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Bruxelles, la Haute École Francisco Ferrer, le Conservatoire royal de Bruxelles, l’École nationale supérieure des arts visuels La Cambre, l’Université libre de Bruxelles ont organisé au cours de l’hiver 2006 une série d’activités sur le thème Autour de Mozart. Dans ce cadre, la Faculté de Philosophie et Lettres nous a chargé d’organiser un colloque sur Die Zauberflöte qui a eu lieu les 1er et 2 décembre 2006 à l’École nationale supérieure des arts visuels La Cambre. Le Conservatoire royal de Bruxelles s’y est associé par un concert de musique de chambre illustrant par l’exécution de quelques arrangements d’extraits du Singspiel certains aspects abordés dans les communications.

Plutôt que de publier les textes des communications, nous avons préféré réorienter fondamentalement le contenu de l’ouvrage en l’axant sur les traductions françaises et italiennes du livret de Schikaneder et sur les représentations du Singspiel, tant en allemand qu’en français, au théâtre royal de la Monnaie à Bruxelles entre 1829 et 2005. Cette optique a obligé quelques auteurs à retravailler leur communication en y intégrant une documentation souvent abondante et originale. D’autres travaux, qui n’ont pas été présentés au colloque, sont venus compléter l’éventail des études consacrées aux représentations sur la scène bruxelloise. Si l’ouvrage y a gagné en unité, sa parution en a été tellement retardée que plusieurs contributeurs ont souhaité mettre à jour leur article, reportant ainsi à nouveau la publication. Nous leur en sommes néanmoins très reconnaissant et osons espérer que leur longue attente sera compensée par la cohérence des douze contributions. ← 9 | 10 →

Pour terminer nous voulons rendre hommage à Robert Wangermée, qui prit en 1964 l’initiative de créer une section de Musicologie à l’Université libre de Bruxelles, qui nous fit partager pendant nos études son intérêt pour Die Zauberflöte, à laquelle il consacra une étude1, et qui ne cessa jamais de s’intéresser, voire d’apporter son aide via le Conseil de la Musique de la Communauté française de Belgique, aux activités musicologiques organisées à l’initiative de l’institution où il enseigna de 1946 à 1990.

1 Robert Wangermée, « Quelques mystères de “La Flûte enchantée” », Revue belge de Musicologie, XXXIV-XXXV (1980-81), p. 147-163.

Die Zauberflöte from Libretto to Score

Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan

Résumé

Pour la partition autographe de Die Zauberflöte Mozart s’est servi d’un livret qui est perdu, mais la similitude avec celui imprimé en 1791 à Vienne par Alberti fait croire qu’il disposait d’une version proche de ce dernier. Les divergences entre les deux sources sont considérées comme la preuve d’une attitude propre à Mozart lors de la composition d’un opéra. Des modifications similaires apportées à des opéras antérieurs destinés au Wiednertheater révèlent cependant qu’il s’agit d’une pratique courante. Ce fait remet en cause l’opinion généralement admise de l’intervention de Mozart dans l’écriture du livret original – une collaboration qui aurait été inhabituelle à l’époque. D’autres anomalies peuvent s’expliquer par les particularités propres au « grosse Oper ».

*

Forty years ago, Peter Branscombe1 enumerated the surprising number and variety of divergences between Mozart’s autograph score2 and Emanuel Schikaneder’s printed libretto of Die Zauberflöte.3 One can draw few conclusions from these variants, since we possess so little ← 13 | 14 → information on the commission and composition of the opera, and on the practices at the Theater auf der Wieden, the stage for which the opera was first composed. The manuscript libretto that Mozart set in the first half of 1791 is lost. Ignaz Alberti’s printed libretto, prepared for the first production, came later, probably coinciding with the premiere.

Important eighteenth-century sources have recently emerged to help evaluate the autograph’s departures from that of the libretto, namely early librettos of Wiednertheater operas and copies of scores, prepared by a group of Viennese scribes associated with this theater. The Wiednertheater copy business, managed by Schikaneder’s actor and singer Kaspar Weiss, appears on the title page of manuscript scores and in several prints.4 While these sources have limitations, they at least provide us with texts (and music) for Wiednertheater operas fairly close to the original productions, and allow for an illuminating comparison of textual readings.

Here I will review variant texts, musical indications and stage directions from the libretto and autograph score of Die Zauberflöte in light of what these new sources reveal about the practices at the Wiednertheater. The results of this investigation may offer context for Mozart’s approach to Schikaneder’s libretto and opera at the Theater auf der Wieden.

First a word of warning: it has often been assumed that Mozart alone was responsible for all the divergences, just as it is often assumed that he helped to write the libretto. But these assumptions are speculative. Schikaneder almost certainly had input into Mozart’s decisions about how to set his libretto; after all, Schikaneder was the impresario and author, as well as the predominant actor in the opera. Schikaneder’s preface to the printed libretto of his opera Der Spiegel von Arkadien mentions that he and Mozart diligently planned Die Zauberflöte together,5 and it seems to have been common knowledge that Schikaneder had significant input in the musical settings of his librettos, including Die Zauberflöte.6 Thus ← 14 | 15 → the precise role and influence of composer and librettist are not easily determined and caution seems wise in these matters.

*

Studies on the librettos of Die Zauberflöte reveal that successive prints were generally not corrected to conform to the readings in the scores. Newly identified Wiednertheater sources suggest this was typical for Schikander’s librettos; the transmission of the text in the libretto remained largely separate from the transmission of the text in the score. Not only Die Zauberflöte but Schikaneder’s other librettos were often recycled for subsequent productions without regard to the text in the score.

In comparing librettos of German supernatural operas from 1743-1791 (see Table 1) one is struck by the amount of detail in Schikaneder’s librettos regarding the stage action. In the case of Die Zauberflöte, one finds extraordinary detail regarding music (these indications are listed in Table 2). Before attempting to explain this level of detail we might recall that librettos had multiple purposes. They were prepared for the censor as well as the composer and the audience. Librettists may have also intended their text to provide other theaters with practical instructions necessary to mount the work. But this conjecture is problematic. The original company would not want other theaters performing a new piece too soon, and proprietary control certainly had a greater financial advantage than the potential sale of librettos and scores.

Table 1. German supernatural operas, 1743-1791

While the censor would require enough detail to make sure that the material was not offensive to the state, the audience would need much less detail. Many indications of stage action and music are superfluous during a performance. Such specificity might be welcome by those who bought the libretto as a souvenir, but hardly a necessity. A significant level of detail however was essential for the composer, who needed such information before setting the music. How else to explain the specific instruments required at various points in the text, and the indications of short musical interjections during the dialogue? This kind of information would be of no value to the censor or the audience member, who sees and hears these events as they occur on the stage. Thus, we are left with the distinct possibility that the libretto of 1791 included early instructions mainly intended for the composer.

Table 2. Musical indications in the libretto of Die Zauberflöte

But why does Schikaneder’s Zauberflöte provide so many musical indications? I believe we can point to several likely reasons. First of all, Schikaneder’s generic term for the libretto was “grosse Oper”, apparently the first time he used this term, with its suggestion of a big court opera. The large cast as well as the number and variety of ensembles is consistent with this genre designation. In fact, there are more ensembles than in any previous opera by Schikaneder, suggesting that this libretto was intended for Mozart, even that Mozart may have requested the ensembles. Additionally, this was the first large-scale German opera by Mozart since the highly successful Die Entführung aus dem Serail ten years earlier. That alone made Die Zauberflöte a special event in the German theatrical world. ← 17 | 18 →

The poster has some unusual features that support the preceding points: Mozart’s name and official title are displayed prominently, as they are on the libretto’s title page. Sometimes Schikaneder did not even mention composers on his posters (for example Paul Wranitzky’s Oberon König der Elfen of 1789). The Zauberflöte poster also announces the libretto with two engravings, one of Schikaneder in costume, and new “artistic” decorations by the theater painter. Finally, the title of the opera is unique in that it refers to a musical instrument. And music is a more important subject in this opera than in Schikaneder’s earlier productions.

*

There are approximately fifty variants between the printed libretto and the autograph score. Some are quite significant while others are minor. These include the following:

1) Minor changes in words, or altered texts by obliterating the original wording, structure and rhyme.

2) Deletion of text.

3) Disregarding or altering musical indications.

4) Changing genre.

Three more problematic changes are:

5) Rhymed verse as well as prose used in accompanied recitative.

6) Changing the order of the strophes.

Résumé des informations

- Pages

- 304

- Année

- 2018

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782807607255

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782807607262

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9782807607279

- ISBN (Broché)

- 9782807607248

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13631

- Langue

- français

- Date de parution

- 2018 (Juin)

- Published

- Bruxelles, Bern, Berlin, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2018. 304 p.