Irish-Argentine Identity in an Age of Political Challenge and Change, 1875−1983

Summary

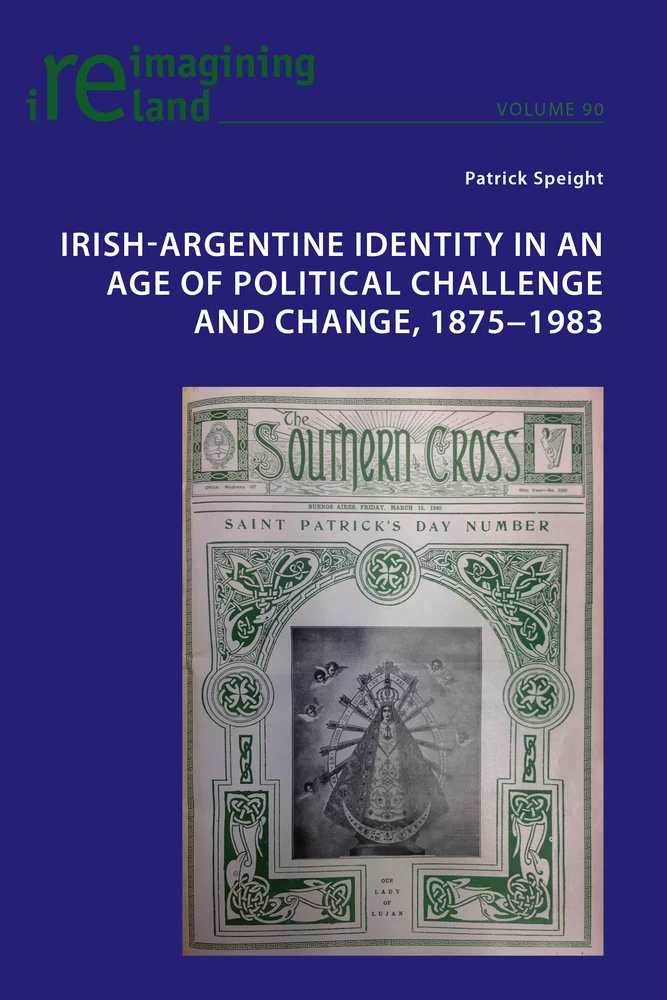

This book is the first comprehensive analysis of the Irish-Argentine community in a hundred years. Using the archive of the Southern Cross, the Irish-Argentine newspaper, it analyses the divisions that opened up in this community as it responded to 1916, the two World Wars, Peronism, the military dictatorship, and the Falklands/Malvinas war.

For generations the Southern Cross reflected and reinforced the conservative values of the community. But in 1968 a new editor would challenge the community over its failure to live up to what he considered to be the essence of being Irish: support for human rights and empathy with the poor.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- About the author

- About the book

- Advance praise

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Identity formation in the Irish-Argentine diaspora

- Chapter 2 The background to Irish emigration to Argentina

- Chapter 3 The Irish put down roots in Argentina

- Chapter 4 The Southern Cross equivocates between assimilation and ethnic separatism

- Chapter 5 World affairs through the lens of the Southern Cross

- Chapter 6 The Irish and Peronism

- Chapter 7 The Irish-Argentines the Southern Cross ignored

- Chapter 8 Tensions between the Irish and Irish-Argentine Pallottines

- Chapter 9 Fr Richards and the Southern Cross during the Dirty War

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Appendix 1: Editors of the Southern Cross, 1875–1991

- Appendix 2: Fahy boys who worked for British and American companies, 30 April 1971

- Appendix 3: William and John

- Appendix 4: Timeline from the British invasion in 1806 to the fall of the last military dictatorship in 1983

- Index

- Series index

Patrick Speight

Irish-Argentine Identity

in an Age of Political

Challenge and Change,

1875−1983

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • New York • Wien

Patrick Speight holds a PhD from Queen’s University Belfast. He is a former BBC radio presenter, reporter and producer who has lived and travelled widely in Latin America. He presented BBC Radio Ulster’s religious affairs programme Sunday Sequence from 1990 to 1995, and produced A State Apart, an archival history of the Troubles. He has also produced websites on notable episodes in Irish history, including William III, the Plantation of Ulster, the Easter Rising, and the Good Friday Agreement.

About the book

This book is the first comprehensive analysis of the Irish-Argentine community in a hundred years. Using the archive of the Southern Cross, the Irish-Argentine newspaper, it analyses the divisions that opened up in this community as it responded to 1916, the two World Wars, Peronism, the military dictatorship, and the Falklands/Malvinas war.

For generations the Southern Cross reflected and reinforced the conservative values of the community. But in 1968 a new editor would challenge the community over its failure to live up to what he considered to be the essence of being Irish: support for human rights and empathy with the poor.

“A fascinating excursion into a still relatively little-known part of the Irish diaspora, which explores, with assuredness and insight, how the Irish retained an identity into the post-WWII period. An excellent contribution to both diaspora history and the history of Argentina.”

Professor Don MacRaild, Professor of British and Irish History,

University of Roehampton

Advance praise

The Irish immigrants who arrived in Argentina between 1840 and 1890 were welcomed. Argentina was different from the English-speaking destinations familiar to other Irish emigrees: the historical antagonism between Catholicism and Protestantism was absent, and Irish immigrants were spared the discrimination experienced by those who settled in America. Argentina was regarded as part of Britain’s ‘informal empire’, and the Irish benefitted economically and socially from being designated ingleses. The co-incidence of interest that developed between Irish-Argentines and British and American capital produced an economically successful community that was keen to protect its social status.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

Identity formation in the Irish-Argentine diaspora

The background to Irish emigration to Argentina

The Irish put down roots in Argentina

The Southern Cross equivocates between assimilation and ethnic separatism

World affairs through the lens of the Southern Cross

The Irish and Peronism ←v | vi→

The Irish-Argentines the Southern Cross ignored

Tensions between the Irish and Irish-Argentine Pallottines

Fr Richards and the Southern Cross during the Dirty War

Appendix 1: Editors of the Southern Cross, 1875–1991

Appendix 2: Fahy boys who worked for British and American companies, 30 April 1971

Appendix 4: Timeline from the British invasion in 1806 to the fall of the last military dictatorship in 1983

Index ←vi | vii→

Figure 1: Fahy Boys who worked for British and American companies, 30 April 1971.

Figure 2: Irish ambassador James McIntyre laying a wreath at the Admiral William Brown monument in Junin on St Patrick’s Day, 2014. (Photographer: Patrick Speight.)

Figure 3: Fr Dunphy aged 30 in 1936.

Figure 4: Fr Dunphy’s Church, Corpus Domini, in Liniers, Buenos Aires.

Figure 5: This cartoon appeared in the Argentine newspaper El Día on 19 December 1945. An extract from Fr Dunphy’s sermon floats in the air: ‘We are not going to simple elections in order for one party to win over another. What is at stake is the future of the fatherland: to be, or not to be?’ (Fr Dunphy). The newspaper headline reads: ‘The state of siege continues’. The strapline reads: ‘What a beautiful little wind blows from Liniers’. (Corpus Domini, Fr Dunphy’s church, is located in the Liniers neighbourhood of Buenos Aires.) ←vii | viii→

Figure 6: Portraits of murdered priests and seminarians: Fr Alfie Kelly with his dog Inca; Fr Pedro Dufau; Fr Alfredo Leaden; seminarian, Emilio Barletti; seminarian, Salvador Barbeito.

Figure 7: The bodies of the three priests, two of them Irish-Argentine, and the two seminarians lie face down on the living room floor. From left to right: Emilio Barletti, Salvador Barbeito, Fr Alfie Kelly, Fr Alfredo Leaden and Fr Pedro Dufau with his hands tied. On Salvador Barbeito’s body the assassins placed a poster by the cartoonist Quino whose character Mafalda points at a policeman’s cudgel and says: ‘Come here? This is the wee cudgel for bashing ideologies’.

Figure 8: The assassins chalked this message on a door: ‘For the dynamited comrades at Federal Security – We Will Be Victorious – Long Live the Fatherland’.

Figure 9: The assassins chalked this message on the carpet: ‘These lefties died for being brainwashers of innocent minds and members of MSTM’.

Figure 10: Fr Fred Richards at the wedding of his niece, María Cristina, on 20 December 1967.

Figure 11: Editors of the Southern Cross, 1875–1991.

Figure 12: Fahy boys who worked for British and American companies, 30 April 1971.

Figure 13: William and John. ←viii | ix→

I would like to thank the many people in Ireland and Argentina who contributed generously in different ways to my research.

I want first to acknowledge the contribution of Professor Keith Jeffery who, despite failing health, was unstinting in his academic guidance. I thank Dr Dominic Bryan who stepped in as my senior advisor following Professor Jeffery’s untimely death, and Professor Peter Gray as my second advisor.

I spent ten months researching in Argentina between November 2013 and August 2014. I interviewed over fifty people in Buenos Aires, San Antonio de Areco, Suipacha, Junin, Mercedes, Rosario, Córdoba and Bariloche, and each one graciously welcomed me into their home. The staff and members of the Fahy Club, in particular, its President Luis Delaney, invited me regularly to their asados and agreed to be interviewed for my thesis.

I would like to thank the editor of the Southern Cross Guillermo MacLoughlin Bréard and the director of the Irish Catholic Association for access to the Southern Cross archive at St Brigid’s College in Buenos Aires. I am grateful to Ricardo McLoughlin who continued to furnish me with information on my return to Belfast.

The staff at the National Library of the Argentine Republic, the National Library of Ireland, the National Archive of Ireland, and Fr Donal McCarthy, S. C. A., archivist of the Pallotine Society in Dublin were unfailingly helpful.

I would like to thank Dr Jonathan Bardon for being an assiduous proof reader and Carlos Otero Speight for casting a critical eye over the Spanish inserts and translations.

Finally, I owe a debt of gratitude to my partner Bronagh Hinds for her support and encouragement over the past four years.←ix | x→ ←x | xi→

ALN Alianza Libertadora Nacionalista

ANCLA Agencia de Noticias Clandestina

CELAM Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano

CGT Confederación General del Trabajo

CGTA Confederación General del Trabajo de los Argentinos

CIDH Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos

EGP Ejército Guerrillero del Pueblo

FAP Fuerzas Armadas Peronistas

FORA Federación Obrera Regional Argentina

GOU Grupo de Oficiales Unidos

ICA Irish Catholic Association

LAP Ley de Asociaciones Profesionales

LPA Liga Patriótica Argentina

MSTM Movimiento de Sacerdotes para el Tercer Mundo

PAN Partido Autonomista Nacional

UCR Unión Cívica Radical

The Irish-Argentine community did not vote for Perón in the 1946 presidential elections and they did not vote to re-elect him for a second term in 1952.1 Voting for a government that promoted workers’ rights and the redistribution of wealth did not sit easily with a community that arrived penniless in Argentina and pulled itself up by its own bootstraps.2 Their decision to vote for the US-supported opposition was at variance with Church advice. When relations between the Church and Perón collapsed they participated in the campaign to overthrow him. Senior figures in the community, like Brother Septimio Walsh3 and José E. Richards,4 played active roles in el panfletismo, a form of political agitation against Perón’s government organised by middle-class Catholic militant groups in 1954.5 On 21 September 1955 Irish-Argentines joined the massive street celebrations that welcomed the military putsch. Twenty-one years later the community welcomed another military dictatorship. On 24 March 1976 a military triumvirate led by General Videla overthrew the government of Isabel Martínez de Perón.6 The military←1 | 2→ cited corruption and her government’s inability to defeat Cuban-inspired terrorism for deposing her democratically elected government.

Between 1976 and 1983 the military junta, with the support of the Church and the business sector, murdered and ‘disappeared’ thousands of its own citizens and left a social wound that has yet to be healed.7 With very few exceptions, the Irish-Argentine community supported the dictatorship.8 Their support was not out of character. It reflected an acceptance in Argentina that the military had the right to intervene in politics if it considered the state was under threat from groups that agitated for communism or socialism. The Southern Cross, the newspaper that represented the views of the Irish-Argentine community since its foundation in 1875, had until 1968 taken a robust stand against left-wing politics.9

When the three branches of the armed forces installed General Videla10 to oversee the Process of National Reorganisation in March 1976, the Southern Cross was under the editorial direction of Fr Fred Richards11 who had taken a principled stand against human rights abuses since his appointment in November 1968. Fr Richards was a Passionist priest at Holy Cross, regarded as the church for the Irish community in Buenos Aires. By March 1976 he had already alienated many of the paper’s traditional conservative readers with his editorials in support of liberation theology12 and the church←2 | 3→ of the poor.13 Within five hours of the military coup, which the mainstream press supported uncritically, Richards’s editorial on 26 March 1976 struck a note of caution. Subscribers soon voiced their opposition in the letters page asserting that Fr Richards’s editorials did not reflect the view of the Irish-Argentine community. Many cancelled their subscriptions, often stretching back generations, in protest. Why did the Irish-Argentine community support the dictatorship? Why did it not speak out when members of its own community were arrested, tortured, and ‘disappeared’?

This book analyses the role played by the Irish-Argentine community during more than a century of political challenge and change that embraced the Easter Rising, the emergence of fascism and the two world wars, the rise, fall and short-lived political resurrection of General Perón whose demise in 1974 led inexorably to the Dirty War that was brought to an abrupt end by Argentina’s humiliating defeat in the Falklands/Malvinas War. It posits the view that the community’s opposition to the redistributionist politics of Perón in the 1940s and their support for the military junta responsible for the Dirty War in the 1970s and early 1980s can be traced back to the process of identity formation that took place in their endogenous community.

From 1875 until the appointment of Fr Fred Richards as editor in 1968 the Southern Cross played a critical role in the process of an identity formation that produced an inward-looking Irish Catholic community. Unused to being challenged by either their Irish or Irish-Argentine priests, the community responded defensively when Fr Fred Richards promoted a vision of the Church that was influenced by the theological changes introduced by the Second Vatican Council14 and the 1968 Latin American Bishops’ Conference in Medellín, Colombia.15 The Irish-Argentine community con←3 | 4→flated the theological revolution that Richards promoted in the Southern Cross with communism and the Cuban Revolution. Richards argued that his opposition to military authoritarianism, his concern for human rights and empathy with the poor was not communism but a reflection of traditional Irish values. Ironically, the ideological divide between the two sides was bridged temporarily when the Irish government condemned Argentina’s invasion of the Falklands/Malvinas in April 1982. The episode led both sides to question the Irish dimension of their Argentine identity.

Chapter outlines

Chapter 1 outlines the social infrastructure within which Irish-Argentine identity was fostered. It then focuses on a discussion about which concept, diaspora or imagined communities, is most suited to explaining the formation of an Irish-Argentine identity.16 The emotive and politically loaded ‘diaspora’ is an integral part of Irish foreign policy but is it the best concept for analysing Ireland’s centuries-old history of migration? Describing the Irish-Argentine ‘diaspora’ as an ‘imagined community’ seems counter intuitive but does this concept provide a greater insight into how the community evolved?

Chapter 2 explores the process of chain migration from Westmeath, Longford and Wexford in the nineteenth century that collapsed after the experiment in mass migration, known as the Dresden affair,17 discour←4 | 5→aged further emigration from Ireland to Argentina. The chapter begins with a critical look at the literature that locates Ireland’s first contact with Argentina in the sixteen century and clarifies the role General John Thomond O’Brien played in the 1820s when he returned to Ireland to encourage emigration to Argentina.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 356

- Year

- 2019

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788744188

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788744195

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788744201

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788744171

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13471

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (July)

- Keywords

- Southern Cross Dirty War Irish-Argentine

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. XII, 356 pp., 13 fig. b/w