Era mio padre

Italian Terrorism of the Anni di Piombo in the Postmemorials of Victims’ Relatives

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

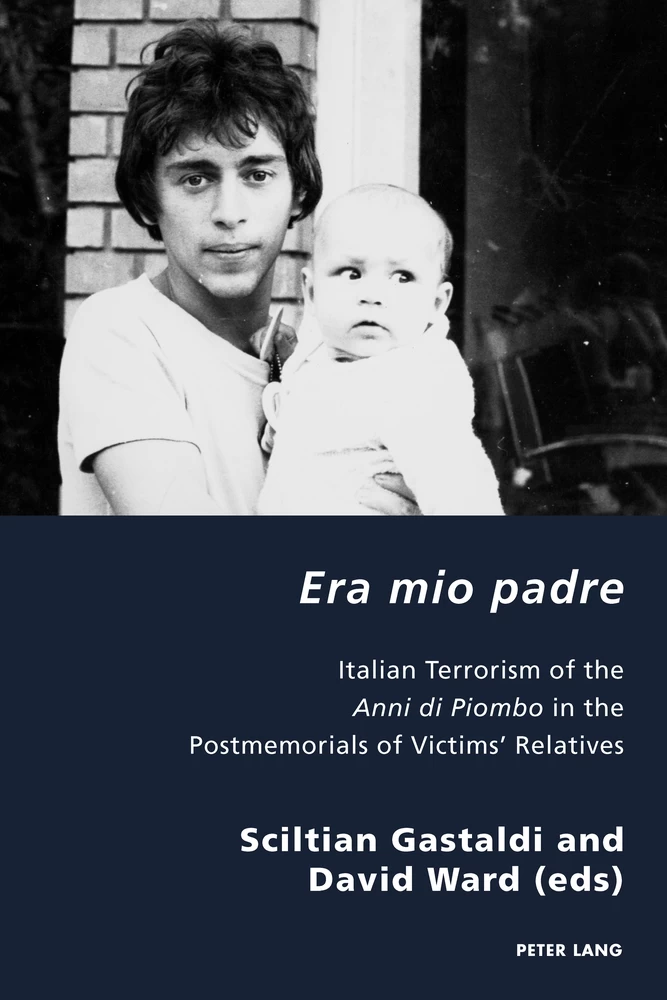

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction (Sciltian Gastaldi / David Ward)

- 1 The Wider Context of the Writings by Victims of Terrorism and their Relatives (David Ward)

- Part I: Figuring the Father

- 2 The Stigma that Dare not Speak its Name: Negotiating Pride and Shame in the Discourse of the Relatives of the Victims of Terrorism (Vasiliki Petsa)

- 3 Il padre assente. Storia e autobiografia nelle memorie di figli delle vittime del terrorismo di sinistra (Barbara Armani)

- 4 La cicatrice dell’evaporazione del padre in Colpire al cuore di Gianni Amelio (Alessandra Diazzi)

- Part II: Case Studies

- 5 ‘Era mio padre’. Scopi culturali differenti negli scritti di tre familiari delle vittime del terrorismo: Mario Calabresi, Benedetta Tobagi e Luca Tarantelli (Sciltian Gastaldi)

- 6 ‘Il caso Moro non riguardi i Moro’. La dialettica tra personaggio pubblico e personaggio privato nella figura di Aldo Moro attraverso gli scritti della figlia (Ilaria Fatta Trabucco)

- 7 ‘Qualunque cosa succeda’. Il testamento spirituale di Giorgio Ambrosoli (Monica Jansen)

- 8 L’ergastolo del dolore. Scopi culturali differenti negli scritti di due familiari delle vittime del terrorismo genovese: Sabina Rossa e Massimo Coco (Sciltian Gastaldi)

- Part III: Histories, Public and Private

- 9 La memoria privata degli anni di piombo (Alessandra Montalbano)

- 10 Vittime: Giovanna Gagliardo’s Cine-history of the Victims of Terrorism (Flavia Laviosa)

- Appendix

- 11 Discorso tenuto in occasione della presentazione de Il Libro dell’incontro alla Sala Zuccari, Senato della Repubblica, Roma, 19 gennaio 2017 (Luca Tarantelli)

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Series index

This book was thought for and is dedicated to all those children of the 1970s and 1980s that history transformed into orphans and collateral victims of political violence. This volume is dedicated to them, and to the memory of all their wonderful, caring, tender and bright fathers. As a child with a living father who has always been a point of reference, I see how cruel life has been with your families, and I wish to abbracciarvi uno a uno.

Thanks go to my family for having borne yet another challenge that decreased the amount of time I could spend with them. Especially my wife Lisa, and Ernesto and Mara, my beloved, vanishing roots. Thank you all also for having listened to my readings.

Special thanks to David Ward, for agreeing to co-edit this volume and for his valuable and constructive suggestions during the many, many e-mail dialogues that planned and developed this project. David has been more than just a pillar of a co-editor, he has been a patient friend.

Thanks also to my liceali students from bucolic Magliano Sabina (Rieti): with all the genuineness and inquisitiveness of your interventions and smiles, you guys have been my personal and professional battery re-charger.

Sciltian Gastaldi

First and foremost, my thanks go to my wife Eugenia and daughter Anna for their everlasting support. In a book about fathers and the impression they leave, my thoughts can only go to my own father Reginald and father-in-law Nunzio and the example of honesty, integrity and decency they both handed down to me.

Thanks, of course, go to Sciltian Gastaldi for inviting me to be part of this project. It has been a pleasure for me to work with such an energetic and enthusiastic young scholar whose commitment to this project was infectious.

We both wish to thank Pierpaolo Antonello and Robert Gordon, co-editors of the Italian Modernities series, for agreeing to publish this book and for coordinating a rocambolesco peer-review process, and making sure we all ended up on the right track. Thanks too to Christabel Scaife, Senior Commissioning Editor at Peter Lang. Special thanks goes to Luca Tarantelli, for his friendship and his appendix contribution, and to Antonio Iosa and Luca Guglielminetti, for their behind-the-scenes work. Our thanks go to all the patient contributors to the volume and to those who responded to our call for papers. Special thanks to Wellesley College’s Faculty Awards Committee for agreeing to contribute to the production costs of this book.

SG & DW

SCILTIAN GASTALDI AND DAVID WARD

Imagine the extremest [sic] possible example of a man who did not possess the power of forgetting at all and who was thus condemned to see everywhere a state of becoming: such a man would no longer believe in his own being, would no longer believe in himself, would see everything flowing asunder in moving points and would lose himself in this stream of becoming. Forgetting is essential to action of any kind, just as not only light but darkness too is essential for the life of everything organic … Thus: it is possible to live almost without memory, and to live happily moreover, as the animal demonstrates; but it is altogether impossible to live at all without forgetting.

— FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE, Untimely Meditations

Il perdono è un fatto esistenziale e morale che riguarda soltanto la coscienza di un individuo e il rapporto fra una vittima e il suo persecutore. Non interessa l’opinione pubblica, non è e non dovrebbe essere una notizia e soprattutto non riguarda la legge né i rapporti fra il colpevole e la società.

— CLAUDIO MAGRIS, Basta con la parodia del perdono

For this book has a further subjective significance for me personally – a significance which I only grasped after I had completed it. It was, I found, a portion of my own self-analysis, my reaction to my father’s death – that is to say, to the most important event, the most poignant loss, of a man’s life.

— SIGMUND FREUD, The Interpretation of Dreams,

Preface to the Second Edition ← 1 | 2 →

Bisogna partire dalle vittime, dalla loro memoria e dal bisogno di verità. ‘Farsi carico’ è la parola chiave. Delle richieste di giustizia, di assistenza, di aiuto e di sensibilità. Lo dovrebbero fare le istituzioni, la politica, ma anche le televisioni, i giornali, la società civile.

— MARIO CALABRESI, Spingendo la notte più in là

Studies devoted to terrorism have been spurred on by recent outbreaks of indiscriminate violence against nations from all over the world that have been targeted by the radical Islamic terrorists of the so-called Da’esh.1 The impact of these violent, large-scale, random atrocities has given impetus to a rigorous analysis that no longer focuses only on the perpetrators and instigators of the terrorist attacks, but also on the victims of these actions.2 The dual attention paid to terrorists and victims represents a novelty and a step forward compared to the way the long season of political terrorism known in Italy as the ‘anni di piombo’ [years of lead] was approached in Italy at least up to 2007.

With its specific concern for the point of view of the victims of Italian political terrorism of the 1970s, this volume is part of the critical field ← 2 | 3 → known as memory studies (which traces the passage from ‘what we know’ to ‘how do we remember it?’). The aim of the volume is, first, to analyse how those children of the victims of both left- and right-wing Italian terrorism of the 1970s have chosen to take on a public stance with memoirs that recall those years; and, second, how in giving narrative form to their experiences they have contributed to a new relationship between history and personal memory. All these authors, pushed by a sense of exclusion to become actors and witnesses ob torto collo, have added their own indispensable tesserae to the mosaic of a national and collective memory of the 1970s that is still largely lacking in Italy today. Both co-editors and authors of the volume seek to reflect critically on the body of texts written both by the children of the victims of terrorism – for example by Mario Calabresi (2007) and Benedetta Tobagi (2009) – for which we have proposed the name ‘postmemorials’ and on the critical studies that have examined the phenomenon from the standpoint of ‘the turn to the victims’ (Glynn 2007). Underlying the entire enterprise is the desire to shift the mediatic spotlight from the point of view of the ex-perpetrators, who up until 2007 enjoyed privileged attention from the media, the church and state institutions, to that of the victims.

The basic coordinates that frame this study are the terms ‘terrorism’ and ‘victims’. Before going further, it will be useful to give clearer definitions to these two often loaded terms

Following the new season of global terrorism of the post-9/11 era, a great many international organizations and scholarly publications have sought to define these two terms. A review of the literature on the question, however, would go far beyond the scope of this volume.

Rather than the concise scientific definition of terrorism based on sixteen elements produced by Alex P. Schmid, we have chosen to adopt the more agile ‘umbrella’ definition elaborated by Rianne Letschert, Ines Staiger and Anthony Pemberton (2010), which identifies three macro-characteristics common to many of these definitions: ‘the intention to cause death or serious bodily harm or damage to property, the targets are often randomly selected persons, in particular civilians or noncombatants, with the purpose to intimidate a population, or to compel a government or an international organization to do or to abstain from doing any act’ (viii), ← 3 | 4 → with the provviso that in the Italian case, many specifically targeted victims were not the victims of indiscriminate bomb attacks in public places, but were carefully chosen by their killers.3

For the other key term too – victims – we have chosen again to follow the definition elaborated by Letschert, Staiger and Pemberton, rather than the detailed one by Schmid (2006), but limiting the definition to the first two levels: primary victims of a terrorist attack, including those who have suffered economic damage as a result of acts of political violence; and secondary victims, that is to say, the dependents and immediate relatives of primary victims.4 In the following pages, writings by both primary and secondary victims will be analysed, as well as writings that centre on them. ← 4 | 5 →

This book insists on the karstic theme of the relationship between history and personal memory. Although cultural memory studies have long had a well-respected academic pedigree (Erll, Nünning and Young, 2010), the current state of the field is still largely indebted to Maurice Halbwachs’ (1877–1945) interesting and original modern study. Halbwachs was the first to establish that human memory can only work in a collective context. However, collective memory is always selective and changes according to the reference group. Thus, the different kind of collective memory that each group holds can determine different ways of behaviour (Halbwachs, 1992). After the Shoah, memoirs written by survivors of an experience that appeared unreal further enriched the critical reflection on collective memory. As Primo Levi explains, the main fear of the victims who survived the Holocaust was that they would not be believed. Once this fear was overcome, some of the victims succeeded in giving verbal expression through memoirs that told the story of their experiences in the death camps characterized by a prose style that used as few adjectives and adverbs as possible. Beginning at least with the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem in 1961, Shoah witnesses began to take on a specific identity and the power of their stories gave rise, above all in the Anglo-Saxon world, to the foundation of a new field, Holocaust studies (also called diaspora studies or Jewish studies) thus creating an academic stage dedicated to the testimony of Holocaust survivors. Almost at the same time, a number of intellectuals of Jewish origin, at times the second generation relatives of the Auschwitz survivors, as in the case of the French sociologist Michel Wieviorka and his sister Annette, a well-known historian, and author of L’Ère du témoin, raised several questions about the relationship between history and memory, about the role of the historian when faced with the witness, and about the difference between history and testimony. These are ← 5 | 6 → texts that are usually written in the first person and inspired by real events that have been experienced firsthand, but often approached indirectly since at the time of the traumatic fact the authors were minors, even infants, their relationship with the past mediated through what Marianne Hirsch, referring to books written by children of Shoah survivors, has called ‘postmemory’. Hirsch’s concept, which is taken up in the present volume most broadly in the first of Gastaldi’s essays, has been defined thus: ‘“Postmemory” describes the relationship that the “generation after” bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before – to experiences they “remember” only by means of the stories, images, and behaviours among which they grew up. But these experiences were transmitted to them so deeply and affectively as to seem to constitute memories in their own right’ (Hirsch, 2016).

Hirsch’s notion of postmemory foregrounds the mediation of the memory that a later generation has of traumatic events experienced by a former one: that is to say, how the children and descendants who have come to know the trauma that beset their parents and relatives in an indirect and mediated, but nevertheless continual, way in the form of diaries, photographs, videos, articles, essays, objects, ceremonies, anniversaries and places ‘inherited’ from their forbears or from those who have dug into the details of that trauma to unearth its micro and macro history. As Hirsch explains, to grow up immersed in a context of family history has led many of the descendants to experience their present almost as if they are prisoners of a past and a memory that risks distorting their experience of that present. It is easy to understand why the co-editors of this volume have chosen to align themselves with Hirsch’s category in their coining of the term ‘postmemorials’ to describe the writings by the relatives of victims of Italian terrorism in the 1970s. These writings are a new and hybrid genre practiced by authors with varying cultural, personal and political aims: a mix of memorials, biography, auto-biography, essay, report, self- and psycho-analysis. Although they are all works of collective memory in which the children of victims give voice to the burden of the memories of their murdered fathers with which they have grown up, postmemorials are characterized by so many different intentions that they can be classified in subgroups. In almost all cases, postmemorials are different from biographies, autobiographies or even the memorials written by former terrorists. ← 6 | 7 → Without ever entering into dialogue with the writings of former terrorists, the writings of the children and relatives with whom this volume is concerned act as a response to the body of former terrorist writings. But they do so by adopting the mode of the second moment of the Hegelian dialectic, namely, that of antithesis.5

A number of intellectuals, such as Luc Boltanski (2000), René Girard (2001), Jean-Michel Chaumont (2002), Susan Sontag (2003), Slavoj Žižek (2006), Cento Bull & Cooke (2013) and Glynn (2007), have recently reflected on what they have seen as a dangerous race toward victimization. In Italy the theme has recently been taken up by a literary critic, Daniele Giglioli, above all in his Critica della vittima (2014). Other interesting reflections by Giglioli include All’ordine del giorno è il terrore (2007) and Senza trauma (2011); as well as by the historian Giovanni De Luna with his La Repubblica del dolore (2011), Una politica senza religione (2013) and Le ragioni di un decennio (2009), and by the historian Monica Galfré with her La guerra è finita. L’Italia e l’uscita dal terrorismo 1980–7 (2014), at least as far as the chapter ‘Ritorno all’uomo’ is concerned.

Both De Luna’s and Giglioli’s reflections take their cue from the symposium ‘Supporting Victims of Terrorism’ held at and organized by the United Nations in New York in 2008. The symposium had a dual function: first, to commemorate the 11 September 2001 attacks; and second, to find a definition of terrorism, after many unsuccessful forays by the United Nations. The task is daunting considering the split between Israel and the Arab world and the objective difficulty encountered by political scientists, sociologists and historians to supply a scientific and univocal definition of ← 7 | 8 → ‘terrorism’; added to that is the fact that, as Giglioli has written in All’ordine del giorno è il terrore, ‘No-one wants to be defined as a terrorist’ (Giglioli, 8). Even the recent terrorist outrages carried out or instigated by Dae’sh in western Europe between 2014 and 2017, in which kamikaze bombers blow themselves up in the midst of vastly different crowds of innocent civilians, are ‘framed’ by their organizers as components of a jihad and ideological war waged against the west. Such actions, like those against western military contingents in numerous theatres of war, are considered by the perpetrators not as acts of terrorism, but acts of heroism and carried out by martyrs of an extreme variant on the Islamic faith. Nevertheless, in 2008 the 192 States represented at the United Nations settled unanimously on a method to work toward a definition of what terrorism is: begin by recognizing its victims. To do this the UN invited representatives of victims of terrorism to come to New York to recount the impact terrorism had had on their lives and how they survived it. The Italian government extended the invitation to Mario Calabresi, son of the police commissioner Luigi Calabresi, murdered by left-wing terrorists from the Lotta Continua group on 17 May 1972. Calabresi, who subsequently became editor of La Repubblica, summed up his speech thus:

Details

- Pages

- X, 274

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781788743273

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781788743280

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781788743297

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781788743266

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13357

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (March)

- Keywords

- Anni di piombo Postmemorials Memory Studies Political Violence Red Brigades 1970s Political Terrorism Italian Terrorism

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2018. X, 274 pp.