Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

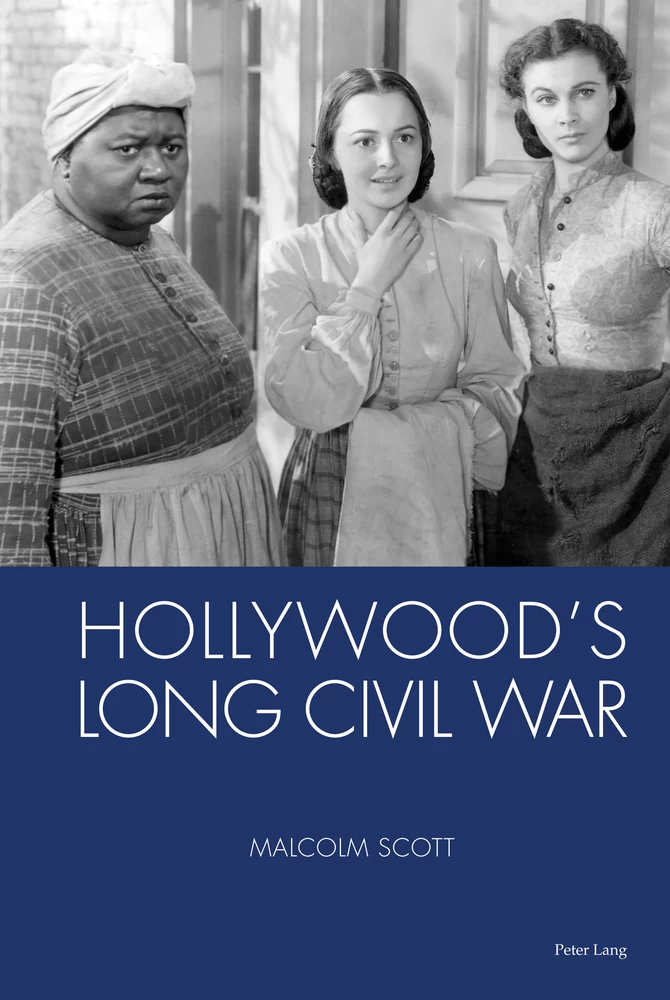

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Author’s Note

- Prologue

- Chapter 1 The Silent War

- Chapter 2 Griffith’s Fame and Shame

- Chapter 3 The War between Wars

- Chapter 4 Windfall

- Chapter 5 Peripheries of War

- Chapter 6 The Civil War Western

- Chapter 7 Responses to Challenge

- Chapter 8 Civil Rights and Cinema

- Chapter 9 New Wave

- Chapter 10 Prehistory

- Epilogue

- Bibliography

- General Index

- Index of Films

Figures

Figure 1.‘Happy’ slaves entertain owners’ guests (The Birth of a Nation)

Figure 3.Gus pursues Flora to her death (The Birth of a Nation)

Figure 4.Ride of the Klan (The Birth of a Nation)

Figure 5.A disconsolate Johnnie rides his piston (The General)

Figure 6.Fall of the bridge: Silent cinema’s most expensive shot (The General)

Figure 7.Scarlett sees the horrors of war (Gone with the Wind)

Figure 8.Escape from a burning Atlanta (Gone with the Wind)

Figure 9.Scarlett’s vow of survival (Gone with the Wind)

Figure 10.Poitier and Belafonte, from Civil Rights to Civil War (Buck and the Preacher)

Figure 11.The First March of the 54th Massachusetts (Glory)

Figure 12.The charge on Fort Wagner (Glory)

Figure 13.General Lee arrives at the battlefield (Gettysburg)

Figure 14.Bayonet charge, Little Round Top (Gettysburg)

Figure 15.Stonewall Jackson’s wounded hand (Gods and Generals)

Figure 16.The President and First Lady opposed in grief (Lincoln)

Figure 17.Lincoln on the silent battlefield of Petersburg (Lincoln)

Figure 18.Newt arms his slave gang (Free State of Jones)

Figure 19.The marking of an independent territory (Free State of Jones)

Figure 20.Captives in chains (Amistad)

←ix | x→Figure 21.African violet and the bonding of races (Amistad)

Figure 22.Slaves of King Cotton (Twelve Years a Slave)

Figure 23.French friends question the Declarer of Independence (Jefferson in Paris)

Figure 24.Jefferson’s heirs tell all (Jefferson in Paris)

Figure 25.Jefferson’s moment of temptation (Jefferson in Paris)

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Natalia Biletska, Computing Officer, School of Modern Languages, University of St Andrews, for the production of the illustrative screenshots in this book.

I express also my thanks to Dr Laurel Plapp, Senior Commissioning Editor, Peter Lang Ltd, for her prompt, patient and expert help in every stage of the publication process.

Author’s Note

My use of lower case characters for ‘black’ and white’ in my text, contrary to a recent trend towards the use of capital letters, stems from my wish to avoid any confusion or contradiction that might arise from the juxtaposition of capitalized terms and the traditional lower case spellings in citations from previous sources or from onscreen titles or subtitles. I recognize the well-founded reasons for capitalization, but on the issues involved here, I shall leave the argument of my book to stand for itself.

Prologue

Long histories

This book is the result of my engagement with two long histories, that of American cinema – Hollywood, to use its popular synonym – from its early silent days to our own times, and that of the American Civil War. Cinema’s longevity need not be argued, having long since exceeded 120 years. Films depicting or related to the Civil War have an almost equally long history as one of cinema’s most popular subjects from earliest times, albeit punctuated, like all film genres, by alternating periods of relative decline and reawakened interest. To refer to the story of the Civil War itself as a ‘long’ history may surprise rather more. It is habitual to think of the war as a time-limited military conflict, in which soldiers in Union blue and Confederate grey fought each other for four years, from 12 April 1861 to 9 April 1865. The war between the armies, however, was just one chapter in a much longer struggle that began long before the guns boomed and left unresolved issues after they fell silent. The twelve-year-long Reconstruction that followed the war was another chapter, an attempt to come to terms with the consequences of the conflict and to determine the way forward for the supposedly reunited nation. But Reconstruction, in the testimony of its most celebrated historian Eric Foner, ‘can only be deemed a failure’,1 leaving the United States still unhealed from the wounds of war and struggling to absolve itself of the original sin that was committed even before the country’s re-founding as an independent republic: racial discrimination and slavery. Despite the various attempts to address the race problem by Civil Rights legislation – in 1866, 1875 and especially in the middle decades of the twentieth century, their cumulative efforts leave a work still in progress, with Confederate flags still ←1 | 2→symbolically flying, and black citizens still less free than whites to pursue their lives without discrimination and harassment. In this sense, the Civil War goes on, a story in search of an ending. The contribution of films to our understanding of this long war – including films of the Civil Rights era that, without being set in the period of the war, raise issues of urgent relevance to the war’s unfinished business – is the subject of this book. Its prime claim to originality lies in its survey, from silent cinema onwards, of films that relate to all three of these chapters, the War, Reconstruction and Civil Rights, to which is added a final look at films that reflect the war’s ‘prehistory’ and which cast a retrospective and instructive light on the war’s longer term origins and significance.

Film and history

It is improbable that anyone interested in the history of the American Civil War would not be interested also in the way in which the war and its antecedents and aftermath have been portrayed in film. Yet the differences between historians’ presentations of the war and those of filmmakers pose problems for all those interested in their interconnections. These differences stem essentially from the divergent creative imperatives of each group. Unlike historians, filmmakers, though they have often laid claims to historical accuracy – whether in advance publicity or in what Jonathan Stubbs calls onscreen ‘prologue texts’2 that set dates and sketch background – have rarely espoused the latter as a first priority and have focused instead, as the principal aim and end product of their industry, on the entertainment value and commercial success of their films. In pursuing these ends, legitimate choices have had to be made as to what extent, in so-called ‘historical’ films, history can be foreshortened, with events transposed or re-ordered in time to achieve greater dramatic or suspenseful effects; whether fact and fiction can be plausibly combined ←2 | 3→or, even more radically, whether history can be transformed into fictional analogies that paint symbolic rather than historical pictures. Melvyn Stokes uses the terms ‘compression’, ‘alteration’ and ‘metaphor’ to refer to the kind of choices that have just been described.3 Allowing such latitude, as is now accepted by most film studies specialists, affirms cinema’s right to offer alternative histories and to present national narratives in which an entertaining representation of the past takes priority over precise historical events, situations and personages. Film historian Gary Gallagher quotes Freddie Fields, the producer of the 1989 film Glory – which portrays a well-documented Civil War event but places fictitious characters in a number of important roles and takes liberties with historical details – as saying: ‘You can get bogged down when dealing with history. Our objective was to make a highly entertaining and exciting war movie.’4 But Gallagher rightly concludes: ‘Yet films undeniably teach Americans about the past – to a lamentable degree in the minds of many academic historians. More people have formed perceptions about the Civil War from watching Gone with the Wind than from reading all the books written by historians since Selznick’s blockbuster debuted in 1939.’5 Whatever their limits as history, such films can draw spectators into a desire to learn more about the war by what they see of it on screen. In the present book, no film that reflects the Civil War will be excluded from mention on the grounds of its departure from historical veracity; even frankly fictitious Civil War westerns will have a chapter to themselves.

Enduring myths

There is a fine line, however, between the cinematic dramatization of history and its falsification by what is often referred to as ‘myth’. This word and its adjectival derivatives ‘mythic’ or ‘mythical’ can carry a positive sense, akin to ‘legendary’ and signalling the raising of historical personages to the elevated status accorded to the heroes of classical mythology. Cinema’s commemoration of Abraham Lincoln’s benevolence to all victims of war and its veneration of Robert E. Lee, sitting nobly astride his famous white horse Traveller, illustrate the point. More often, however, myth-making takes on pejorative undertones, more approximate to untruth than to acceptable and legitimate versions of history. In this perspective, cinematic myth is not an innocent rewriting of history, but can be guilty of adopting a polemical or politically charged view of the past in order to justify a partial and biased vision of the present. Such an objection is effectively expressed in Bruce Chadwick’s The Reel Civil War: Mythmaking in American Film, which, despite its jokey title, defends the traditional preference for verifiably ‘real’ historical accuracy by punctuating its descriptions of films with straight historical summaries that bring Hollywood’s wilful myth-making to the surface. Arguing that the Civil War was ‘hopelessly distorted’ in films from the silent era onwards, leaving audiences knowing ‘little or nothing of the truth’ and ‘little understanding of how the conflict changed American life’, Chadwick describes the clichés encountered in the typical Civil War movie: ‘a moonlight and magnolias saga that featured trees dripping with Spanish moss, gentlemen drinking mint juleps on the veranda, women prettifying themselves for the ball and countless soldiers becoming instant heroes’.6 He goes on to list the principal myths identified by him in films of this type: that southerners are invariably portrayed as underdogs, despite the historical fact that at times during the war they seemed to have the upper hand and could with better fortune have emerged as victors; that they are typically depicted as rich slaveholders living on luxurious plantations, ←4 | 5→whereas history teaches that a large majority of them, including many who fought in the war, owned no slaves at all and lived their lives as struggling farmers; that southern women are often shown as ‘frail’ and ‘delicate’ in order to solicit audiences’ sympathy; that slaves, when they are mentioned at all, are presented not as justly resentful and potentially rebellious victims of a brutal and inhuman economic system but as ‘helpful mammies, obliging butlers, smiling carriage-drivers, joyful cotton-pickers and tap-dancing entertainers’.7

The mythology of the world of King Cotton, of wealthy planters and of ‘the happy and contented black’ is challenged also by Edward D. C. Campbell’s earlier book The Celluloid South: Hollywood and the Southern Myth.8 Both Campbell and Chadwick observe that such distortions were not solely dreamed up by filmmakers but were initiated four decades before the advent of cinema in the wake of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse in April 1865,9 and identify the means by which they were propagated: southern school text books, magazines, romantic literature and popular song. What soon became known as the Confederacy’s Lost Cause, a term popularized by a book written in 1868 by the Virginia journalist Edwin A. Pollard,10 was given further academic credence four decades later – just as the first short Civil War feature films were being made – by the Dunning School of Historiography. The latter was the creation of a Columbia University professor, William Dunning, whose account of Reconstruction was accepted for several decades as the established version of its subject.11 The Dunning doctrine comforted many already convinced southerners by its contention that the secessionist states had done no wrong. They had simply defended their constitutional right to practise slavery, and had been drawn into a war in which they were the moral victors, defeated militarily by a richer and more populous enemy ←5 | 6→after a long and gallant struggle. Reconstruction, according to Dunning, had been both punitive and futile. His views attracted strong support not only from diehard admirers of the Confederacy but also from those who desired the reconciliation of the former warring sections. For the United States to advance in rediscovered harmony as the principal economic power of the new century, the Civil War had to be presented as a conflict that had no insurmountable reason for ever having taken place other than the federal government’s refusal to heed the South’s appeal to ‘states’ rights’ and to accept its legitimate decision to secede.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 282

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800794238

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800794245

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800794252

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800794221

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (September)

- Keywords

- Civil War Hollywood Civil Rights movement Gone with the Wind African America Malcolm Scott Hollywood’s Long Civil War

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XIV, 282 pp., 25 fig. b/w.