Classroom Observation

Researching Interaction in English Language Teaching

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Preface

- Contents

- Introduction: Classroom observation revisited (Götz Schwab)

- Part I Classroom interaction from a micro-analytical perspective

- Classroom interactional competence of primary EFL teachers (Holger Limberg)

- Instruction-giving in the primary English classroom: Creating or obstructing learning opportunities? (Karen Glaser)

- Conversation analysis gets mobile: Student participation in a bilingual primary classroom in Germany (Götz Schwab)

- Part II Multimodal insights into classroom discourse

- Address terms as reproaches in EFL classroom management (Revert Klattenberg)

- Turn-taking in PowerPoint presentations: A model of floor management during slide shifts (Maximiliane Frobenius)

- Multimodal repair initiation through rejections by teachers in the primary EFL classroom (Julia Schaper)

- Part III Video-based reflective practice and intervention studies

- All kinds of special: Using multi-perspective classroom videography to prepare EFL teachers for learners with special educational needs (Carolyn Blume / Torben Schmidt)

- Assessing pre-service teachers’ reflective classroom observation competence in English language teaching (Gabriele Blell / Friederike von Bremen)

- Developing secondary students’ writing skills: Affective and motivational effects of a feedback intervention with learners of English as a foreign language (Vera Busse / Ulrike Krause /Judy Parr / Petra B. Schubert)

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Series Index

Götz Schwab

Introduction: Classroom observation revisited

Accuracy of observation is the equivalent of accuracy of thinking.

Wallace Stevens

Abstract In this survey chapter, classroom observation is explored from different perspectives and traditions in order to discover the magnitude of the research into this field of institutional language teaching and learning. It also discusses what aspects need to be considered when planning and conducting empirical research in this field. The chapter begins by discussing why classroom research is conducted before moving on to various characteristics of language classrooms. It continues by exploring particular ways of studying interaction in language classrooms. Much emphasis is placed on the question of how to use different tools and methodologies in classroom research. In addition to a number of important basic theoretical notions, this chapter considers various practical aspects of how classroom observation can be done. These aspects range from observation schemes to audio-recordings, videography and mixed-method approaches. The chapter also includes descriptions of recent technological developments in the area by making reference to significant works in the field in addition to studies which are presented in this volume. The final conclusion discusses future developments and how classroom research can successfully and effectively be conducted to better understand the complexity of the evolving processes of language acquisition in institutional settings.

Keywords: classroom research, research methodology, classroom observation, videography, conversation analysis, participation, multimodality

1 Introduction

When considering English Foreign Language (EFL) learning, we most likely imagine an institutional setting (e.g. a classroom) where students and a teacher meet in an effort to achieve what is oftentimes discussed under the broader notion of Second Language Acquisition (SLA). Even if this is a quite limited view on the matter, it is by no means an exaggeration to consider the language classroom as one of the most important settings where language learning takes place. Therefore, it is not surprising that scholars have been exploring this setting for ←9 | 10→over 50 years to discover what exactly takes places in order to ascertain how language learning takes shape (Allwright & Bailey, 1991; Walsh, 2011).

Systematic classroom observation, however, did not gain momentum until the mid-1970s when applied linguists and language pedagogues attached more and more importance to classroom interaction and how language acquisition evolves in institutional settings (Allwright, 19881; Brumfit & Mitchell 1990). Investigations into classroom activities, usually referred to as classroom (-centered) research (Allwright & Bailey, 1991), can also be used to inform teacher training. Therefore, it seems reasonable that it can also be of interest to practicing teachers. This chapter investigates classroom observation in the field of second or foreign language education. This investigation relies heavily on a statement of Howard (2010), who explains that “classroom researchers use observation of lessons in action to identify what, how and why activities take place (pp. 84–85).” For this line of research, the chapter attempts to answer the following questions: Why do classroom observation? What is classroom observation? What can be observed? How can we observe classroom activities? A final comment on the topic is provided discussing possible future developments in the field of classroom observation and research.

2 Why do classroom observation?

A lot of what is considered as second and foreign language learning takes place in institutional settings such as classrooms. Therefore, it is not surprising that Wajnryb (1992) talks about “the primacy of the classroom” (p. 13) when conducting research in the field of Second and Foreign Language Acquisition (S/FLA) and Teaching English as a Foreign/Second Language (TEFL/TESL).

Wragg (1999, vii-viii) gives, among others, the following two reasons why classroom observation is of such great importance and why this needs to be a topic for researchers and teachers alike, that is, delusion and routine. As observers, we often simply see what we want to see and dismiss or overlook unpleasant activities that do not fit into our research paradigm. Due to the fact that many of us have seen in numerous lessons, we are not aware of the details anymore because “it is so easy to look straight through events that might hold significance” (Wragg, 1999, p. 10). Language classrooms are much more complex than ←10 | 11→we often admit or realize. This might be one reason why classroom research, despite its many efforts over the past decades, is still a field of inquiry where many questions remain under discussion.

When language learning takes place in classrooms, we need to know how this is happening in order to find out about the mechanics of institutional language acquisition. These insights then need to be transferred to those who can be seen as in charge of much of the process: the language teachers.

3 What is classroom observation? Part I – terminological considerations

Often in the literature, the term “classroom observation” is not explicitly defined. This might be because both parts of the compound, classroom and observation, are taken-for-granted lexical items with a clear denotative and a deliberately broad if not obscure connotative meaning. Everyone seems to know what a classroom is like (Tudor, 2001), and observation appears to be a common activity (Wragg, 1999). However, to put it bluntly, that is not the case at all. The complex nature of the language classroom and its inherent processes of unfolding interactions can easily be overlooked and many aspects disregarded (van Lier, 1997; Wragg, 1999). We therefore need to explore this term more closely before considering how we can observe language classrooms.

Van Lier (1988) defines the L2 classroom as “the gathering, for a given period of time, of two or more persons (one of whom generally assumes the role of instructor) for the purpose of language learning” (p. 47). Tudor (2001) describes the language classroom as “a controlled learning environment, namely a place where students work on the language according to a carefully designed learning programme under the supervision and guidance of a trained teacher” (p. 105). This might form the basis for researchers trying to discover the ways in which language learning becomes observable. This could be particularly relevant when looking at how “an identifiable group with its own cultural characteristics” (van Lier, 1988, p. 41), that is, students and instructors, shapes the process of learning in its own particular way. According to Johnson and Christensen (2008), the very art of looking at these activities can be depicted as follows: “[I];n research, observation is defined as the unobtrusive watching of behavioral patterns of people in certain situations to obtain information the about phenomenon of interest.” (p. 147, emphasis in original).

However, instead of only devising a theoretical framework of classroom observation, we might also approach the term by considering the following images in Wragg’s (1999, p. 112) comprehensive work on classroom observation:

←11 | 12→Classroom observation first and foremost involves one’s perspective and how an individual, onlooker, or participant, perceives the world. Obviously, there are different ways of observation and we cannot help taking one or the other viewpoint as our perspective on the setting (Block, 1996). As observers our starting point might look more like this even if we know about its constraints and weaknesses.

Therefore, classroom observation can first be considered as the attempt to look into a (language) classroom using different perspectives in order to understand the complexity or ‘ecology’ (van Lier, 1997) of what is happening.

Certainly, we need to specify our focal point and decide on what we would like to discover or achieve. Even when we take a more phenomenological approach being open to whatever might occur as most interesting or prevailing at a certain point in our inquiry, attention has to be given to one focal aspect. This, however, should not distract the observer from the overall linguistic and social richness of the language classroom and its learning environment.

4 What is classroom observation? Part II – methodological considerations

Observation involves what can be seen and watched from the outside, in other words, visible discernable activities and behavior. We can watch what people do, listen to what they say, or look at the interplay between gestures, artefacts and language use. However, it is not possible to see directly and without obstruction into people’s mind and observe their thinking or how they comprehend the situation (Schramm & Schwab, 2016). We can only attempt to infer from what we observe in an effort to make sense of it. This is also true for language ←12 | 13→learning processes in institutional settings: “When observing an L2 classroom in action it is clear that no direct link can be made between observable behavior and language development. Learning is not generally directly and immediately observable” (van Lier, 1988, p. 91). Nonetheless, it is, as van Lier continues, the best way of becoming familiar with how (language) acquisition is taking shape and internalized by the language learner, especially if “learning is regarded as doing rather than having” (Walsh, 2011, p. 158, emphasis in original).

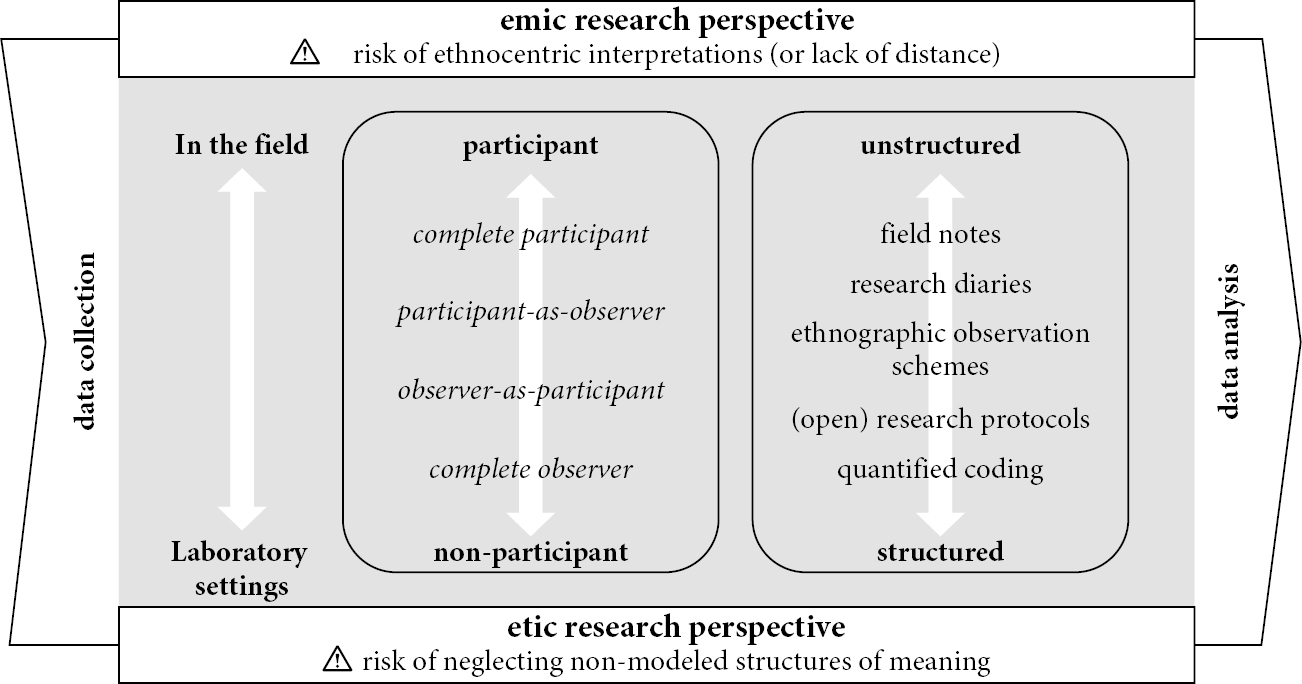

In order to do classroom observation there are a variety of approaches which are outlined in the following. These various dimensions of scientific observation are often described along certain dichotomies such as structured vs. unstructured, etic vs. emic perspective, participant vs. non-participant, online vs. offline, direct vs. indirect, macroscopic vs. microscopic, or self- vs. other observation. Since some of them overlap, they are discussed together. In line with Schramm & Schwab (2016) the most important dimensions are delineated briefly here.

For a more general distinction they suggest to differentiate between structured and unstructured observation where structured implies a somewhat rigorous system of pre-defined research foci, often found in observation protocols ←13 | 14→(e.g. Helmke & Helmke, 2014; Walsh, 2006), evaluation studies (e.g. DESI-Konsortium, 2008) or (video-based) reflective practice (e.g. Sert, 2015; Blell & von Bremen and Blume & Schmidt in this volume). Unstructured stands for an unmotivated and phenomenological view of the classroom in question, often seen in ethnographic or ethnomethodological studies (e.g. Limberg, Schaper or Glaser in this volume).

As could be seen in Figures 1 and 2, observation involves one’s perspective of the unfolding interaction. Unlike what is often called the outsider’s perspective or etic view, ethnographically oriented studies on classroom interaction in particular are based on what is called an emic perspective, that is, the viewpoint of the participating subject (Dörnyei, 2007; Seedhouse, 2005). In Conversation Analysis (CA), particularly Conversation Analysis (for) Second Language Acquisition (CA-SLA) (e.g. Hall & Verplaetse, 2000; He, 2004; Markee & Kasper, 2004; Sert, 2015 and Frobenius in this volume), the importance of the emic perspective as a methodological stance to better comprehend why participants do what they do, that is, “why this now?” (Schegloff & Sacks, 1973, p. 299), has often been postulated (Rampton et al., 2002; van Lier, 1988, 1990). An emic perspective is therefore inextricably linked to natural settings (such as classrooms) whereas an etic perspective often refers to more laboratory settings.

The distinction between what one can observe as a researcher and how things are perceived by the very subjects is part and parcel of the notion of participation in the field of inquiry. The manner in which researchers participate in the field has become pivotal to classroom observation.

The contrastive pair, participant vs. non-participant observation (which is similar to direct vs. indirect observation), has been further developed by Johnson and Christensen (2008) who see the role of researchers in field work as a continuum2 containing four distinct poles:

Complete Participant – Participant-as-Observer – Observer-as-Participant – Complete Observer

A Complete Participant is someone who is indistinguishable from the subjects being observed. S/he, however, does not inform the observee(s) of her or his intentions. This differs from the role of Participant-as-Observer which instead relates to a more transparent approach of letting the observed know about the observation. Since s/he is (temporarily) part of the group, the observer can act as an insider. This is unlike the main activity of an Observer-as-Participant, which ←14 | 15→is to observe the group without being part of the group. Her or his presence is not hidden or disguised. Finally, being a Complete Observer is, by definition, a role that takes an unambiguously etic perspective, often without the observer informing the subjects that they are being observed.

Both extreme poles, Complete Participant as well as Complete Observer, are ethically questionable due to the fact that the research subjects are kept in a state of ignorance and thus these poles are “totally incompatible with ethnographic research which crucially depends on a relationship of trust” (van Lier, 1988, p. 39). Classroom observation therefore leans towards the roles of Participant-as-Observer and, to an even greater extent, Observer-as-Participant.

A more general idea of observation can be seen in Spada and Lyster’s (1997) juxtaposition of macroscopic and microscopic perspectives. Macroscopic refers to the concept that researchers approach the field of study, for example, a language classroom, in a broad and comprehensive fashion, such as when comparing certain linguistic or interactional issues across different classrooms. A microscopic perspective is more specific and focused on a certain phenomenon3.

An important distinction is also related to the way research is actually conducted and what instruments are used. The differentiation between what Schramm and Schwab (2016) label offline vs. online observation is related to when the observation actually takes place, that is, at the very moment of its collection (online) or in retrospect (offline). Most studies in classroom research clearly prefer an online approach as researchers usually participate in one way or another in the on-going classroom activity. Nonetheless, some approaches do include both perspectives, particularly when observation is used for reflection where the observees watch and analyze their actions retrospectively after the lesson (see Blell & von Bremen and Schwab in this volume).

The distinction between direct and indirect observation is also bound to the time when the actual observation takes place, and additionally relates to the instruments that are used for the study. Indirect observation is subsequently conducted using, for example, questionnaires, interviews or makes use of self-reporting data such as research diaries. This is in order to gain insights into what participants intended to achieve. Direct observation takes place in the actual classroom using schemes, protocols or audio and/or video recordings. ←15 | 16→According to van Lier (1988), direct observation is rooted in ethnography and always adopts an emic perspective.

A final distinction can be made between other- and self-observation. Most of the research done in the field can be considered as other observation. However, there is a growing number of studies based on action research methodology which promote self-observation as part of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) (for a comprehensive overview see Mann & Walsh, 2017).

Frequently all these dichotomies are just the two extreme poles of a continuum on which researchers navigate through their research interests. It certainly depends to a great extent on the chosen methodology whether a study leans more towards one or the other pole. Figure 3, adapted from Schramm & Schwab (2016), encapsulates some of the main aspects of classroom observation previously discussed.

In all this there is the important issue of privacy and data protection which has become a sensitive topic in research, particularly in authentic learning situations such as classrooms (Johnson & Christensen, 2008); it is an issue that has raised the “ ‘ethical stakes’ ” (Dörnyei, 2007, p. 64). Regardless of what kind of research is conducted, researchers and participating educators have to ensure that they address topics such as sharing information with participants, data ownership and protection, anonymity, and their relationship with participants (Dörnyei, 2007). Regarding access to the classroom or data presentations at ←16 | 17→conferences or in publications, these questions and issues can create obstacles, if not an inconvenience to one’s research inquiries. However, researchers have to accommodate these ethical considerations and find reasonable ways of adapting the design and outline of their studies to the given circumstances. In video-based multimodal studies, we need not only mask (‘anonymise’) the participants’ names, we also need to conceal their faces using various means to protect the participants’ anonymities. For example, in this volume, authors use blurring software (Klattenberg), verbal description (Schaper), and original artwork based on the video recordings (Frobenius).

This is why “a good researcher has a sense of social responsibility, that is, accountability to the field and more broadly, to the world” (Dörnyei, 2007, pp. 17–18).

5 What can observation look like?

Details

- Pages

- 276

- Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631816547

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631816554

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631816561

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631810910

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16732

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (April)

- Keywords

- conversation analysis observation methodology foreign language teaching teacher training micro-analysis videography reflective practice multimodal interaction intervention study

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2020. 276 pp., 47 fig. b/w, 13 tables.