Unacknowledged Legislators

Studies in Russian Literary History and Poetics in Honor of Michael Wachtel

Summary

The volume is dedicated to the distinguished authority in Russian poetry and comparative literary studies, Professor of Princeton University Michael Wachtel.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- By the Numbers: Notes on Analyzing Russian Verse Rhythm (Barry P. Scherr)

- Again on Bakhtin and Poetry, with a Very Long Preface on the Perfidious Cult (Caryl Emerson)

- Casti, Salieri, and Peter the Great: On Salieri’s Heroicomic Opera “Cublai, gran kan de’ Tartari” (Mario Corti)

- «Безрукий инвалид» в пушкинских «Моих замечаниях об русском театре» (Алексей Балакин)

- Заметки к «байронщизне» П.А. Вяземского: «бледные выписки французские» и цензурные вычерки (Мария Баскина)

- Две строки и три соседа: контексты одного пушкинского перевода (Дарья Хитрова)

- What Can We Do with Books from Pushkin’s Library? (Alexander Dolinin)

- Banishing Catherine II: The Bronze Horseman (Olga Peters Hasty)

- Из комментария к «Пиковой даме» (Михаил Безродный)

- The Rhetoric of Pretendership in Pushkin and Njegoš (Andrew Wachtel)

- Подражание как средство создания русского национального театра (Любовь Киселева, Карина Новашевская)

- Жуковский и Гоголь (Из истории одного места) (Илья Виницкий)

- Чужой (о стратегии вхождения Гоголя в пушкинский литературный круг) (Екатерина Лямина, Наталья Самовер)

- Aleksandr Pushkin and Dmitrii Grigorovich as Listeners to Peasants (Gabriella Safran)

- The Making of the ‘Russian Orthodox Milton’: Fedor Glinka’s Quest for Epic Form (Pamela Davidson)

- Стихотворение Тютчева «Умом – Россию не понять…»: материалы к пониманию (Александр Осповат)

- Итальянский поэт-дилетант в Одессе (Стефано Гардзонио)

- Александр Элиасберг: из писем к П.Д. Эттингеру (К.M. Азадовский)

- Материалы к учению о рифме в башенной Академии стиха (Геннадий Обатнин)

- Б.В. Томашевский о Весах (Николай Богомолов)

- Московский Лингвистический Кружок и становление русского стиховедения (1919 ‒ 1920) (Игорь Пильщиков, Андрей Устинов)

- Slaying the Dragon of Symbolism: Nikolai Gumilev’s Poem of the Beginning (Emily Wang)

- Из Именного указателя к Записным книжкам Ахматовой: Круг Вячеслава Иванова – Владимир Пяст (Роман Тименчик)

- Anna Akhmatova and the Nobel Prize (Magnus Ljunggren)

- Из юношеских лет Елены Тагер (Материалы к биографии. 1895–1924) (М.Г. Сальман)

- “Zzyyz —— zhzha!..” Textual Criticism and Textual Politics in a Poem by Velimir Khlebnikov (Ronald Vroon)

- Я-oн, установленное лицо. К биографии Клавдии Якобсон (Владимир Нехотин)

- «Наше объединение свободное и добровольное»: Николай Заболоцкий в ОБЭРИУ (Андрей Устинов, Игорь Лощилов )

- Недописанная книга Валентина Кривича (А.В. Лавров)

- Из материалов Федора Сологуба в собрании М.С. Лесмана (Маргарита Павлова)

- From My Recollections (Magnus Ljunggren)

- А.С. Штейгер. Письма к В.В. Морковину (А.Л. Соболев)

- Заметки о «Подвиге» / «Glory» (Григорий Утгоф)

- «Silentium» О. Мандельштама: стихотворение с почему-то не замеченным ключом (Олег Лекманов)

- Письма Надежды Синяковой Борису Пастернаку (Анна Сергеева-Клятис)

- Pushkin as Camouflage: Pasternak’s Posthumous Dialogue with Tsvetaeva in Doctor Zhivago (Alyssa Dinega Gillespie)

- Из пастернаковской переписки. События нобелевских дней глазами брата (Лазарь Флейшман)

- «Краем глаза, через полстолетия»: Неизданная антология Эллиса «Певцы Германии» (Федор Поляков)

- И.С. Тургенев на страницах поднемецкой печати 1942–1945 гг. (Борис Равдин)

- Мать Мария: израильские отзвуки трагической судьбы (Владимир Хазан)

- Степун и Валентинов (Вольский) (Manfred Schruba)

- Series index

By the Numbers: Notes on Analyzing Russian Verse Rhythm

Barry P. Scherr

Dartmouth College

This article takes its inspiration from Michael Wachtel’s “Charts, Graphs, and Meaning: Kiril Taranovsky and the Study of Russian Versification” (2015), which contains a critical appraisal of Taranovsky’s influential monograph devoted to Russian binary meters – that is, iambic and trochaic verse.1 That work – originally published in Serbian (1953) and translated into Russian more than half a century later (2010) – built on earlier research, especially by Boris Tomashevsky (1929), and in turn has provided a model for subsequent quantitative investigations into the nature of Russian verse. As Wachtel (2015: 190) observes, broad statistical studies in any case are not likely to be of great help for interpreting the individual poem. Their use is more for comparative purposes: to set a poem, a group of poems, or all the work of a poet against the practice of others or against the norms for a particular period. However, his main concern in this article is that the massive amount of statistical information presented in the second and far longer portion of Taranovsky’s study ignores some important subtleties of Russian rhythm that he does consider in the first part. Among other things, the extensive tables and graphs only take into account whether the strong positions (or ictuses) in a line are stressed or unstressed and ignore the possibility that some stresses may be – indeed, are – more salient than others. Furthermore, the analyses in that second part give no consideration to how verse rhythm may be affected when stresses appear on a line’s weak positions (those that, according to the meter, are normally not stressed): so-called hypermetrical stressing.

At the outset, I want to emphasize that the value of what Taranovsky accomplished remains. He detailed the predominant rhythmic tendencies for the major iambic and trochaic meters; provided extensive data that allow for seeing the rhythmic characteristics of particular poems, authors and periods against a broader context; showed that over the decades certain meters developed new rhythms; and, most fundamentally, described the forces that gave rise to the ←11 | 12→main rhythmic qualities of Russian verse. Nonetheless, it is important not only to appreciate his achievements, but also to be aware – as Taranovsky himself was – that this one work is hardly the final word in terms of comprehending how Russian poetry operates. Wachtel has brought up important points that I would like to expand upon, but first I want to address two additional matters regarding Taranovsky’s magnum opus.

1. Laws or Propensities?

In an earlier article (Scherr 2014: 343–44) I noted that the two “laws” Taranovsky describes might better be labeled propensities or norms. His “law of regressive accentual dissimilation” describes the way in which stronger and weaker ictuses tend to alternate in the line. The virtually constant stress on the final ictus (at least through the nineteenth century) makes it the strongest, and as a result the penultimate ictus is quite weak. This alternation of strong and weak gradually becomes less pronounced moving from the back to the front of the line; hence it is “regressive.” The law of “the stabilization of the first ictus after the first weak syllable in the line” simply means that in iambic lines the first ictus (which falls on the second syllable) tends to be strongly stressed, while in trochaic meters the first ictus, which falls on the first syllable, is usually one of the less frequently stressed strong positions in the line. Although Taranovsky derived these laws by examining just the binary meters, more recent studies (e.g., Gasparov 1974: 277) have also shown that they affect the patterns of omitted stresses in dol’nik verse, which contains either one or two syllables between ictuses and has been widely used since the early twentieth century. The laws would seem to have little relevance for ternary poetry, which rarely omits ictuses. However, the one ictus that lacked stress in more than extremely rare instances during the nineteenth century was the first ictus (i.e., the first syllable) in dactylic meters, suggesting that the second of these laws is valid for ternary verse as well. In the twentieth century some poets have come to omit stresses more often, including within ternary lines. When they do, the first of these laws can affect the resulting pattern. Gleb Struve, albeit not referring to Taranovsky, has listed numerous instances when Pasternak’s ternary verse contains an unstressed strong position. When this happens in his amphibrachic trimeter poems, the great majority are on the second foot – just as Taranovsky’s law would predict (Struve 1968: 240–43). Also, of the 29 anapestic pentameter lines in Pasternak’s Deviat’sot piatyi god that omit a stress, in 21 cases the omission occurs on the fourth foot, making the penultimate ictus by far the weakest (1968: 236–37), again in keeping with the law of regressive accentual dissimilation. The clear influence of Taranovsky’s laws on ←12 | 13→dol’nik verse and their occasional effect even on poems written in ternary meters suggest that Taranovsky was describing something fundamental to the way in which Russian verse operates.

However, for all that Taranovsky clearly discovered important phenomena, his very use of the term “law” can be misleading, for laws of poetry are not exactly the same as laws of nature. Maksim Shapir, in an article devoted to the limits of exact methods in the humanities, put the matter succinctly: “Any restriction on Russian iambic lines of the same length can be occasionally violated, be it forbidden reaccentuations, the constant stress on the final foot, or the equal number of syllables in each line up to the last metrical stress.” (Shapir 2005: 51). As it turns out, Taranovsky’s laws are violated far more frequently than any of the three unusual instances that Shapir cites. First, as Taranovsky notes on a number of occasions, the two laws function harmoniously in iambic meters with an odd number of ictuses and in trochaic meters with an even number of ictuses, but otherwise they clash, and one has to yield to the other. For instance, in the iambic tetrameter the first law predicts strong stressing on the fourth and second ictuses with corresponding weaker stressing on the third and first, while the other law predicts a strong first ictus. Sometimes one of these tendencies has predominated, sometimes the other.2 But that is not the only issue. The existence or absence of a caesura can also influence a line’s rhythm. Most iambic hexameter poetry is written with a caesura after the sixth syllable, which in turn often creates a so-called “symmetrical” rhythm, with the effect of regressive accentual dissimilation interrupted at that mid-point of the line. Thus, the third ictus, which should be weak, is instead strong, and the two halves of the line act semi-independently: relatively strong first and third ictuses surround a weaker second, at the same time that relatively strong fourth and sixth ictuses surround a weaker fifth. Other factors may also counteract these laws. In an article devoted to Andrei Belyi’s use of the iambic tetrameter, Taranovsky noted that while the rhythmic structure of Belyi’s iambic tetrameter verse initially resembled that of Pushkin, over roughly six years (1903–09) he experimented extensively with the rhythm of that meter, culminating during the last two years of this period with quite low stressing over the first three ictuses. He must therefore have consciously striven to omit stresses, and by weakening both the first and second ictuses, he was “violating” both laws (Taranovsky 2000: 300–3).

Close examination of Taranovsky’s own data soon reveals that these laws essentially describe the ways in which the language itself produces a “natural” ←13 | 14→rhythm, which may, however, be overridden in a number of ways: by the intentional efforts of a particular poet, by a conflict between the laws, or by such factors as the presence of a caesura or the predominant syntactic structures found in a poem. Interestingly, in later years Taranovsky himself had refined his thinking about the nature of verse, and had he reworked his 1953 study it almost certainly would have included some major modifications.3 His recognition that the laws essentially express tendencies inherent in the language can be seen in an important 1969 letter to his Russian colleague, Vladislav Kholshevnikov. There he points out that the interaction of his laws was meant not to describe how the rhythmic structure of Russian binary meters evolved, but only how it was formed (Khvorost’ianova 2003: 322).4 He further states that these laws are based on the rhythmic structure of the Russian language, and that he intends to write about that topic. Tellingly, several years later he writes to Kholshevnikov and refers approvingly to an article by Miroslav Červenka (1973), in which the chief point is that the “rhythmic impulse” of verse results from the structure of the given language (Khvorost’ianova 2003: 347). Taranovsky never wrote his intended article on the topic, but if he had he no doubt would have mentioned the propensity (in Russian and other languages) to avoid strong stressing in close proximity. As a result, relatively strong and weak ictuses alternate, while the near-obligatory stress on the final ictus means that the application of this pattern will be regressive. The absence of strong stressing on the first syllable results from the nature of Russian word stress: disyllabic words stress the second syllable slightly more often than the first, and words with more than two syllables are far less likely to stress the first syllable than one of the others.5

←14 | 15→As for Belyi’s experiments and their seeming flouting of Russian’s natural rhythmic tendencies, he was hardly the only modern poet to employ unusual verse rhythms. In that 1969 letter to Kholshevnikov, Taranovsky remarked: “But what isn’t there in the twentieth century? At the beginning of the twentieth century poets consciously experimented, and verse began to evolve less spontaneously than before” (Khvorost’ianova 2003: 323). The poetry that Taranovsky examined for his major study of verse rhythm predated the twentieth century; in more modern times the overall practice has become far less uniform and often less in conformity with the norms that Taranovsky found for earlier verse. Indeed, Taranovsky’s own investigations into iambic tetrameter verse of the early twentieth century – originally published in Serbo-Croatian already in the mid-1950s – had shown that poets consciously experimented in order to create a distinctive rhythm of their own (Taranovsky 2010a).6 This striving for originality often meant resisting the natural rhythms of the language. In short, the “laws,” while important, need to be seen as a starting point for understanding what happens in Russian verse, not as an absolute determinant.

2. Lacunae

Taranovsky’s massive study contains data for thousands of lines written in each of the major binary meters and thus would seem definitive for describing the predominant features and rhythmic structures found in Russian verse of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. However, in that same 1969 letter Taranovsky ←15 | 16→offers a brief but telling remark: “My calculations in regard to the eighteenth-century trochaic tetrameter are clearly insufficient as Drage has shown in his two articles (in the London Slavonic Review)” (Khvorost’ianova 2003: 321). Taranovsky had looked at a little over 3000 lines in that meter by five leading poets (Lomonosov, Trediakovsky, Sumarokov, Derzhavin and Krylov), a sampling that would appear sufficiently large and varied to present a good picture of eighteenth-century practice. In his commentary he focused on changes in the predominant rhythm between the eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries (2010: 73–80). His two laws predicted weakly stressed first and third ictuses, and a strong second. Such was the case already in the eighteenth century, he observed, but these differences were heightened in the nineteenth, with the odd-numbered ictuses becoming still weaker and the second stronger, to the point of turning into a constant in the verse of some poets.

Charles Drage, in his more concentrated research, examines more than six times the number of lines by no fewer than sixteen poets (Drage 1960: 369). While Taranovsky limited himself to major poets of the era, Drage casts a wider net, which pulls in some relatively minor figures. However, poets of less renown may nevertheless reveal much about what is going on in verse during a given period. (Mikhail Gasparov [1994], referring to the acmeist poet Vsevolod Rozhdestvensky, once stated that “such a ‘third-rate not a bit worse than a first-rate’ [poet] is very suitable for investigating the typical traits of literary schools and processes.”7) Drage presents a more complex picture, finding little evidence for a gradual transition from eighteenth-century practice to that of the nineteenth (1961: 353–58; see also Table 1, p. 367). He places the sixteen poets into three groups. The first, which includes all but one of the authors studied by Taranovsky along with three others, seems to move very slowly toward his nineteenth-century model; the second, possibly influenced directly by folklore models, already reveals a rhythm much like that in the following century; while the third group shows a mix of directions (for instance, Kapnist has the lowest stressing on the second ictus and relatively high stressing on the first and third, thus lessening rather than heightening differences between ictuses). As Taranovsky realized, the findings in Drage’s articles meant that the claim of a straightforward evolution in the rhythm of the trochaic tetrameter needed to be modified.

←16 | 17→More recently, Sergei Liapin (2019) has pointed to another gap in Taranovsky’s data. The iambic tetrameter was the most widely used meter in Russian verse throughout the nineteenth century and remains a leading form to the present day. Taranovsky divides the usage of that meter into several periods and presents the data over two tables: “From 1739 to 1835” and “From 1820 to the End of the Nineteenth Century” (2010: 84–93; Tables II and III in the Appendix). In all, he examines more than 67,000 lines written in this meter – again, seemingly enough of a sampling to be representative of the whole. After looking at two stages of a “transitional period,” he further notes a difference between those poets who originally used the transitional rhythm and later began to employ the “new” rhythm of the nineteenth century, as opposed to those who use that newer rhythm from the start. If in the eighteenth century the effect of the law governing the beginning of the line predominated, making the first ictus stronger than the second, then in the new rhythm regressive accentual dissimilation held sway, resulting in the second ictus being stressed significantly more often than the first. This trait was even more pronounced among poets who employed the new rhythm from the start, for whom stressing on the second ictus averaged 96.8 % and that on the first only 82.1 %. Liapin (2019: 126) makes the point that the second part of the nineteenth century is in fact “poorly represented” in Taranovsky’s data in terms of both lyric and, especially, narrative poetry. Indeed, the notes for Table III (Taranovsky 2010: 348) reveal that he analyzed four works, containing just over 1900 lines, from the 1850s, and those are the only post-1842 poems represented in all his data for the iambic tetrameter.8 Liapin, examining post-1850 narrative verse, finds that the second ictus is stressed much less often, and the third more often, than in Taranovsky’s figures for “From 1820 to the End of the Nineteenth Century.” Liapin associates the difference with a syntactic feature of narrative verse: its greater use of enjambement results in syntactic structures that are more likely to omit stress on the second ictus (2019: 126–28). However, the trend noted by Liapin might also suggest a movement toward some of the rhythmic structures that Taranovsky noted among poets at the beginning of the twentieth century in lyric as well as narrative verse (2010a: 396–97).9 The ←17 | 18→chief point, though, is that Taranovsky’s original study essentially ignored all poetry written in the iambic tetrameter after 1860 and indeed examines only a handful of works after 1842; hence whatever developments took place in the use of the iambic tetrameters over the latter decades of the nineteenth century are not reflected in his overall figures. As both Drage and Liapin show, the data provided by more focused analysis can not only complement but also complicate the understanding of Russian verse rhythm seen in Taranovsky’s study.

3. Formulating Hierarchies of Stress

Let us now turn to the first of the two points that Wachtel raises: simply having two categories of syllables, stressed and unstressed, appears to be something of a simplification (Wachtel 2015: 188–89). As he notes, Viktor Zhirmunsky argues for at least four categories of stress: the full stress of content words; a kind of “half-stress” that is found, for instance, on pronouns (whether mono- or disyllabic) when they appear on a strong position; a lighter stress that appears on those same words if they fall on a weak syllable (the stressed syllable of a disyllabic pronoun may appear on a weak position in ternary meters); and words that are always unstressed, such as monosyllabic prepositions – except in those special word combinations where they happen to be stressed (Zhirmunskii 1923: 127–28; cf. his earlier discussion of metrically ambiguous mono- and disyllabic words, 102–20). As we shall see, Mikhail Gasparov later adapted these distinctions for some of his analyses of verse rhythm.

However, Zhirmunsky did not stop there but went on to suggest a set of intermediate possibilities. After assigning “1” to the stress on a content word and “0” to a syllable or word that is always unstressed, he then placed different fractional values on the strength of pronouns and other words that do not carry a full stress, depending on the syntactic structure and their position in the line. He begins with “¼” “½”, and “¾” but quickly introduces still other possibilities: “⅜” and “⅛” (1923: 129). Somewhat later in his study Zhirmunsky complicates the situation further, with references to intonation and the type of verse. He states, citing a passage from Eugene Onegin, that in conversational or rhetorical verse some content words receive greater emphasis than others. Here he uses a different numerical system, giving pronouns in strong positions a “1” while the stressed ←18 | 19→syllables of content words receive a “2” or a “3” (Zhirmunskii 1923: 165–66).10 However, in meditative elegies or melodic lyrical poems (the Russian example he gives is from Fet) stresses for content words stay largely on the same level, with the verse not giving any special prominence to individual words.

With all this, Zhirmunsky does not delve into every matters. For instance, Tomashevsky (1929: 111, 121) suggests that a stressed syllable preceded by one or more unstressed syllables is perceived as stronger than one that is not – an issue that Zhirmunsky does not explore. And, like Tomashevsky, Zhirmunsky considers only the stressed syllables in a word, not dealing with, for instance, the greater prominence given to an immediate pre-tonic syllable than to post-tonic. Still, Zhirmunsky does enough to indicate at least two problems with attempting to account for all levels of stress: the matter quickly becomes too complicated for ready application in actual practice, and not everyone will perceive subtle distinctions between the prominence of syllables in the same way (one person’s “⅛” stress may be another’s “¼” or even “½”).

While Zhirmunsky never seems to have provided a fully elaborated system, several decades later there was a notable effort to advance his ideas about stress and to use them for a comprehensive analysis of Russian rhythm. Vadim Baevsky began what was to be a nearly half-century career of major contributions to the study of versification with an article in Voprosy Iazykoznaniia (1966), where he referenced Zhirmunsky (1923) and other major works on Russian verse in the course of establishing his own method for delineating degrees of stress (and unstress).11 For a first publication in the field by someone with essentially no formal training in the topic it was a remarkably mature and well-informed work, although his assignments of relative stress receive a detailed explanation only in an article he published the following year (1967: 53–54). He eventually employed a computer program to help apply his methodology to more than 11,000 lines of poetry in some 442 poems that were written during the 1950s and 1960s in one of four meters: iambic tetrameter and pentameter, trochaic tetrameter and pentameter. The most detailed publication on this topic (Baevskii and Osipova 1973) describes his findings for the trochaic tetrameter and was later republished in modified form (Baevskii 2001), where it is more readily accessible.

←19 | 20→While Baevsky’s mathematical apparatus can seem intimidating, he essentially carries out what amounts to an averaging of syllable strength. He uses five numerical designations (“1” / “1.5” / “2” / “2.5” / “3”) to indicate the prominence of syllables. For instance, the stressed syllable of a content word that falls on an ictus is assigned a “3,” while monosyllables that are always unstressed (conjunctions, particles, etc.) are among those that receive a “1.” Unlike Zhirmunsky, Baevsky marks each syllable within words: an immediate pre-tonic syllable receives a “2”; the first post-tonic in the middle of a word a “1.”

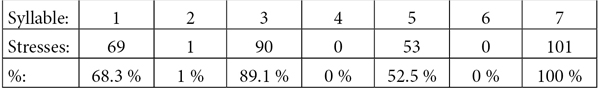

His system yields certain advantages over Taranovsky’s for analyzing the verse line. Using five categories for the relative strength of syllables rather than the simple binary division of stressed versus unstressed clearly provides more information about the rhythm, as we can see in a set of poems by Pasternak. Although Baevsky does not specify in most instances the poems he examined, he states that the Pasternak poems he used come from Kogda razguliaetsia. The trochaic tetrameter poems in that cycle have the following stressing on each syllable:

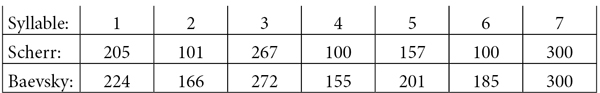

The traditional methodology only shows stressing on the ictuses; here I have also included the weak positions, since those are important for Baevsky’s approach. To make my numbers comparable to Baevsky’s, it was necessary to count each unstressed syllable as a “1” and to multiply the number of stresses by “3” (since the traditional approach does not distinguish between degrees of stress), divide the totals by the number of lines in the sample, and then multiply the result by 100. Those analogous figures are presented below, followed by Baevsky’s:

In his system many of the unstressed syllables in words are assigned a “1.5” or even a “2.” Thus, the greater differences between the two systems will appear in the more lightly stressed strong positions (syllables 1 and 5) as well as in all the weak positions (the even-numbered syllables in a trochaic line). Conversely, the constantly stressed last strong position receives the same value in both systems, while the heavily stressed third syllable in the line receives only a little more weight with Baevsky. What do we learn from his approach? Most obviously, it ←20 | 21→reveals a more nuanced picture of the rhythmic movement. In 34 of the 40 trochaic tetrameter poems (by 16 poets) studied by Baevsky, the fourth syllable of the line is emphasized the least, a consequence of the strong stressing on the third syllable (Baevskii 2001: 162). The line’s sixth syllable tends to be relatively prominent, almost as much so as the lightly stressed third strong position (syllable 5). This effect arises in large part because whenever the obligatory stress on syllable 7 is occupied by a multisyllabic word, syllable 6 is pre-tonic and thus receives a value of “2.” This kind of examination further allows for seeing how certain poets create a greater contrast between the strong and the weak positions than do others, while on a more subtle level it reveals that for some poets the overall “weight” of the line tends to be distinctly lighter or heavier than the norm. Also, of course, it becomes possible to compare individual poems against the averages and thus pick out particularly distinctive aspects of the rhythm in a given poem or in the overall practice of a poet that might otherwise pass unnoticed.

At the same time the method has its limitations. Some of these result from the particulars of Baevsky’s choices; others, though, are inherent to the overall approach. My chief problem with Baevsky’s system is the assignment of values to the prominence of syllables. He states, for instance, that the stressed syllable of a content word on a weak position receives a value of “2.5,” while pronouns (and other words that are considered to be “ambiguously stressed”) also are assigned a “2.5,” whether appearing on a strong or a weak position. Thus, in analyzing the first line of Evgenii Onegin («Мой дядя самых честных правил») he gives «Мой» a “2.5” (Baevskii 1966: 87), while he similarly assigns a “2.5” to the first word in the line «Цель творчества – самоотдача» from Pasternak’s «Быть знаменитым некрасиво…» (Baevskii 1967: 54). However, I would submit that most readers would stress the opening word of Pasternak’s line significantly more strongly than that of Pushkin’s. Another example is placing a value of “2” on final open syllables – for example, the second syllable of «дядя» in that line from Pushkin – allotting them 2/3 the prominence of a stressed syllable, even though vowels in the immediate post-tonic position are normally greatly reduced. In general, then, I find that he tends to overweight the prominence of many syllables, especially those on weak positions, thus making the line’s rhythm less distinctive than it feels in reality. Baevsky himself admits that his system fails to take into account all the distinctions in the prominence of individual syllables – for instance, by not differentiating between ambiguously stressed words on strong and weak position in the line (Baevskii 1967: 54; 2001: 154), whereas Zhirmunsky and other scholars have all remarked that the rhythmic impulse of a verse line makes these words more distinctly stressed when they coincide with a strong position. Another problem is the relatively small corpus ←21 | 22→of works that he managed to examine. He had obviously intended for this project to be extended by himself or by others, but, for instance, in the case of the trochaic tetrameter we are left with the data for just the 40 poems, all written within two decades. For whatever reason – perhaps questions were raised about the methodology or perhaps the task of assigning a specific strength to every syllable proved too time-consuming – there was no follow-up to the original effort.

Notably, the very problems discerned by Wachtel are not really addressed through this approach. First, like Taranovsky’s method, it does not tell us whether hypermetrical stressing is present even while offering more information about the weak positions. For example, the first weak position (syllable 2) has relatively low prominence in the Pasternak poems that were analyzed, yet it does contain a hypermetrical stress; conversely, the relatively high prominence of the sixth syllable does not result from any hypermetrical stressing, but from numerous syllables that, by his method, are assigned a value higher than “1.” And such matters as the increased emphasis that may result from phrase stress or syntactic structures are also not taken into consideration. An equally large issue, particularly for Baevsky’s approach but to an extent for Zhirmunsky’s as well, is the lack of a generally accepted way for determining the relative strength with which each syllable is pronounced. In looking at ambiguously stressed words on the weak positions Zhirmunsky starts off with the relatively simple notion of a half-stress, but for the sake of precision he quickly goes to quarter-stresses and then eighth-stresses. It is not clear where the process would stop. And does his distinction between “rhetorical” and “melodic” verse mean that it is no longer possible to apply the same values to stressed syllables in both? As for Baevsky, he seems to have created values that are too close together numerically and fail to recognize the relative strength of stressed syllables. Surely the difference between the stress on мой and that on дядя is greater than that implied by “2.5” and “3,” and is the prominence of the first syllable in дядя only 50 % greater than on the second (“3” versus “2”)?

Perhaps most tellingly, both Baevsky and Zhirmunsky soon resorted to paying attention only to whether an ictus was stressed or unstressed, seemingly ignoring their earlier claims regarding the relative strength of syllables. In the course of an article on Gumilev’s verse, Baevsky (1994: 87–88) presents the rhythmic patterns for the poet’s iambic pentameter verse with reference only to the stressing on the strong positions (presumably counting the ambiguously stressed words as fully stressed when they coincide with an ictus). In studies that attempt to create a periodization of the works by individual poets, he similarly only considers the presence or absence of stress on the strong positions for several characteristics: (a) the percentage of lines omitting stress on half or ←22 | 23→more of the strong positions (Baevskii 2001: 186), (b) the differences in stressing between neighboring ictuses (2001: 232), and (c) the different frequency of stressing on specific ictuses from one period to the next (2001: 239). In all these instances there is no longer an effort to assign relative stress. Even within his 1923 study, Zhirmunsky abandons the effort to assign specific weights to ambiguously stressed words as soon as he turns to tonic verse. For instance, in quoting Blok’s «Вхожу я в темные храмы» he marks only the syllables that carry stress according to the dol’nik meter and simply ignores the «я» in that first line of the poem (1923: 185). Many years later, in quoting Lomonosov’s iambic tetrameter, he indicates only whether ictuses are stressed or unstressed. He does not discuss degrees of stress and ignores monosyllabic pronouns that do not coincide with an ictus (Zhirmunskii 1968:21). The same is true in a posthumously published summary article on the question of verse rhythm; there he mentions various “secondary” rhythmic features, but the primary factor is again the presence or absence of stress on the ictuses (Zhirmunskii 1974). In short, even those who devised these relatively comprehensive approaches to distinguishing among degrees of stress found them unwieldy and came to abandon them.

4. Heavy and Light Stresses

A further problem with the systems proposed by Baevsky and Zhirmunsky is the failure to consider fully the effect of verse rhythm: ultimately small distinctions in the strength of stressing on particular words or syllables have relatively little effect on the rhythmic inertia of verse. That said, it seems desirable to take into account the obvious difference in prominence between, say, a stressed noun and a monosyllabic pronoun. In the 1970s, Mikhail Gasparov revived the notion that Zhirmunskii (1923:102) had put forth before elaborating more subtle distinctions among types of stress. Words are assigned to one of three categories: those that are always stressed (nouns, adjectives, verbs other than auxiliaries, most adverbs), words that are always unstressed (particles, prepositions, conjunctions) and words that are ambiguous (pronouns, monosyllabic numerals, auxiliary verbs, etc.). The words that are always stressed are said to have a “heavy” stress; those that are ambiguous a “light” stress. Granted, applying these labels is not quite as clear-cut a process as it sounds: various factors, particularly syntax, may affect a word’s prominence. For instance, the adverb «так» is regarded as ambiguously stressed when it accompanies other adverbs, but it is always stressed when it stands alone. A monosyllabic pronoun in a weak position may nonetheless be considered fully stressed if it receives logical emphasis. Similarly, a normally unstressed word, such as the conjunction «и» is regarded as containing a light ←23 | 24→stress if it is juxtaposed with an ellipsis or a dash. (Gasparov 1974: 132–38; cf. Zhirmunskii 1923: 95–120 for a more detailed discussion of the exceptions that can arise). Like Zhirmunsky – as well as Tomashevsky (1929: 95–96) and Taranovsky (2010: 37–38) – Gasparov, taking into account the rhythmic inertia imposed by the meter, counts ambiguous words as stressed when they coincide with an ictus. Unlike the others, though, Gasparov then goes on to consider further how the distinction between heavily stressed words and those with ambiguous stress is important both for verse rhythm in general and for hypermetrical stressing.

In an article originally published in 1977, Gasparov (1997) noted that not only are the strong positions in a line stressed more often than would result from a “natural” use of the language, but also that the stresses on the ictuses are “heavy” more often than would be expected – in other words, the more prominent ictuses tend to avoid light stresses. A complementary observation by Igor Pilshchikov (2019) focuses on poems where a single rhythmic form dominates – say, the form that omits stress on the third ictus of a tetrameter line. In such poems, those lines that are fully stressed will often have a lightly stressed word, whether monosyllabic or disyllabic, specifically on the ictus that is unstressed in the poem’s predominant rhythmic form. In other words, the ictus that is stressed less frequently “attracts” lightly stressed words on those lines where it is stressed, thereby emphasizing the main rhythm of the poem. This is further evidence for a tendency noted by Gasparov (1974: 198) for ambiguously stressed words to be overrepresented on the weaker ictuses, just as heavy stresses turn out to be overrepresented on the stronger ictuses.

5. Hypermetrical Stressing

Now we can turn at last to Wachtel’s other concern, hypermetrical stress. Placing a stress on the weak position of a line singles the word out and heightens its semantic significance; in addition, such stresses can alter the rhythmic quality of the entire line (Kaiumova 1998: 6–7). At the same time, scholars have long observed that hypermetrical stress occurs much more frequently at the beginning of a line rather than inside it, where the disruption of the rhythm is likely to be more acute. Gasparov, who did some important work on this topic, treats ambiguous words differently here, counting them as light hypermetrical stresses when they appear on weak positions (whereas in his broad statistical studies of verse rhythm they are regarded as unstressed when they do not coincide with an ictus). Therefore, in his data on hypermetrical stressing he typically provides three figures: the total, and then numbers for those that are light and those that ←24 | 25→are heavy. Gasparov initially considered the issue of hypermetrical stressing in regard to ternary meters. He observed that in amphibrachic verse the frequency of hypermetrical stressing on the first syllable was close to the expected amount (based on theoretical models derived from the frequencies of word types and their usage in Russian). Anapestic verse stressed the first syllable even somewhat more often than anticipated. In the rest of the line, though, any hypermetrical stressing was significantly lower than the models predict, with the avoidance of heavy hypermetrical stresses especially pronounced. The minimal hypermetrical stressing within the line and the relatively high frequency of heavy stresses on the ictuses tend to emphasize the main rhythmic inertia of the line (Gasparov 1974: 180–90). In briefer remarks on the binary meters, he noted that hypermetrical stress in an iambic line occurs most often when the first ictus is unstressed (so that the line would not begin with three unstressed syllables), and thus the frequency of hypermetrical stressing is to an extent related to the types of line that a poet uses (1974: 194).

In his 1977 article Gasparov elaborated on these matters, further relating them to the way in which verse tends to emphasize its rhythmic underpinnings. In terms of hypermetrical stressing, his findings, based on studying close to 25,000 lines of iambic tetrameter poetry by 22 poets from the eighteenth through the twentieth centuries, provide further evidence that, as with the ternary meters, poets tend to use hypermetrical stressing within the line far less often than would be expected if they were not trying to avoid it (Gasparov 1997: 212; compare his theoretical figures for the iambic tetrameter with those actually observed in the work of individual poets). At the same time, the usage at the beginning of the line tends to be close to what the models predict. What is more, heavily stressed words comprise less of all hypermetrical stressing than their frequency within the language as a whole would suggest. About 35 % of monosyllables are heavily stressed, but they generally account for no more than 30 % of the hypermetrical stresses at the beginning of lines and only around 5-10 % of such stressing within the lines (Gasparov 1997: 207). In other words, the two most disruptive aspects of hypermetrical stressing in terms of rhythm – the use of heavy stresses and the placement of stresses on weak positions within the line – are underrepresented in verse.

The data on hypermetrical stressing can reveal much about the practice of individual poets. Kolmogorov and Prokhorov (2015: 201–3) examined a narrower body of poetry than did Gasparov (and appear to have counted only what Gasparov would call heavy stresses), but their figures demonstrate, for instance, that Derzhavin, unusually, adhered close to what the natural rhythms of Russian would suggest in his use of hypermetrical stressing both at the beginning ←25 | 26→and within his iambic lines. Blok, conversely, in at least a couple of his poems used hypermetrical stressing on the first syllable of lines significantly more often than the theoretical model predicts and essentially avoided it within the line. Kaiumova (2010: 391) has shown that the higher than normal use of internal hypermetrical stressing in Trediakovsky’s iambic verse contributed notably to the sense that his lines display a cumbersome rhythm. A relatively frequent use of heavy hypermetrical stresses within the line distinguishes the anapestic trimeters of Lev Mei in those instances when he was attempting to write folklore imitations (Bakhor 1990: 92–93). In short, the frequency of hypermetrical stressing – especially of the heavy variant – can be distinctive both for a given poet as well as for a certain portion of a poet’s work. Unfortunately, studies like those just quoted here remain uncommon. Neither Gasparov himself nor most other researchers have done much either to pursue further how light and heavy stressing may affect verse rhythm in general or to provide statistical studies of hypermetrical stressing.

What can we conclude from these further comments on Taranovsky’s exploration of binary meters and on the issues raised by Wachtel? First, although Taranovsky’s laws help explain the rhythms that naturally arose in Russian verse, they are neither all-encompassing nor binding: such matters as the prevalence of certain syntactic structures can affect rhythm, while since the end of the nineteenth century it has not been unusual for poets to resist the natural tendencies imposed by language. Second, the statistics compiled by Taranovsky are highly reliable insofar as they go, but he is providing only samplings. In some instances, as with the eighteenth-century trochaic tetrameter, a more comprehensive study reveals tendencies that are not evident from his data alone; in others, there occur gaps in the coverage. There is, then, a need for further analyses, particularly of verse written during the more recent periods, which has received relatively sporadic analysis. Third, while Taranovsky regarded the strong positions in a line simply as stressed or unstressed, efforts to apply a fine-grained approach to the prominence of individual syllables turn out to be relatively complex and ultimately do not necessarily provide significantly more information. Rather, distinguishing between light and heavy stresses – while admittedly not accounting for all the gradations that occur – nonetheless offers a more refined sense of verse rhythm without creating an overly cumbersome system. Fourth, to account for this distinction and to record hypermetrical stress two supplements to the kind of tables Taranovsky provided are necessary: (1) a breakdown of the heavy as opposed to the light stresses on each ictus, and (2) a recording of hypermetrical stressing, again distinguishing between light and heavy.

←26 | 27→Such an approach would require greater effort on the part of researchers and might best be presented through a series of charts rather than a single all-inclusive table, but at least one model for such an analysis already exists.12 This more thorough examination of what actually is happening on each syllable of the line would reveal additional information about the practice of individual poets, allow for more extensive comparisons among authors and bodies of work, and have the potential to provide a deeper understanding of how verse rhythm functions.

References

Baevskii, V.S. 1966. “O chislovoi otsenke sily slogov v stikhe al’terniruiushchego ritma.” Voprosy Iazykoznaniia, XV, no. 2, 84–89.

Baevskii, V.S. 1967. “Chislovye znacheniia sily slogov v stikhe al’terniruiushchego ritma.” Filologicheskie Nauki, X, no. 3, 50–55.

Baevskii, V.S. 1994. “Nikolai Gumilev – master stikha” In Nikolai Gumilev: Issledovaniia i materialy; Bibliografiia, comp. M.D. El’zon and N.A. Groznova (St. Petersburg: Nauka). Pp. 75–103.

Baevskii, V.S. 2001. Lingvisticheskie, matematicheskie, semioticheskie i komp’iuternye modeli v istorii i teorii literatury (Moscow: Iazyki slavianskoi kul’tury).

Baevskii, V.S. 2007. Roman odnoi zhizni (St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriia).

Baevskii, V.S. and L.Ia. Osipova. 1973. “Algoritm i nekotorye rezul’taty statisticheskogo issledovaniia al’terniruiushchego ritma na EVM ‘Minsk–32’,” Mashinnyi perevod i prikladnaia lingvistika, vyp. 17, 174–95.

Bakhor, T.A. 1990. “Stikh fol’klornykh stilizatsii L. A. Meia.” In Literatura i fol’klor: Voprosy poetiki, ed. E. Iu. Moshkova (Volgograd: Volgogradskii gosudarstvennyi pedagogicheskii institut). Pp. 84–94.

Červenka, Miroslav. 1973. “Ritmicheskii impul’s cheshskogo stikha.” In Slavic Poetics: Essays in Honor of Kiril Taranovsky, ed. Roman Jakobson, C. H. van Schooneveld, and Dean S. Worth (The Hague: Mouton). Pp. 79–90.

Chukovskii, Kornei. 2002. “Tretii sort.” In his Sobranie sochinenii v piatnadtsati tomakh. Vol. 6 (Moscow: TERRA-Knizhnyi klub). Pp. 105–15.

←27 | 28→Drage, C.L. 1960. “Trochaic Metres in Early Russian Syllabo-Tonic Poetry.” Slavonic and East European Review, 38, no. 91, 361–79.

Drage, C.L. 1961. “The Rhythmic Development of the Trochaic Tetrameter in Early Russian Syllabo-Tonic Poetry.” Slavonic and East European Review, 39, no. 93, 346–68.

Gasparov, M.L. 1974. Sovremennyi russkii stikh: Metrika i ritmika (Moscow: Nauka).

Gasparov, M.L. 1994. Personal letter to author, December 18. MS.

Gasparov. M.L. 1997. “Legkii stikh i tiazhelyi stikh.” In his Izbrannye stikhi. Vol. 3: O stikhe (Moscow: Iazyki russkoi kul’tury). Pp. 196–213.

Kaiumova, V.F. 1998. “Sverkhskhemnye udareniia v russkoi poezii XIX – nachala XX veka (na materiale chetyrekhstopnogo iamba).” Aktual’nye voprosy v oblasti gumanitarnykh i sotsial’no-ekonomicheskikh nauk. Vyp. 1. Pp. 6–11.

Kaiumova, V.F. 2010. “Ritmika sverkhskhemnykh udarenii v poezii Lomonosova, Sumarokova i Trediakovskogo (na materiale 4-stopnogo iamba).” In Otechestvennoe stikhovedenie: 100-letnie itogi i perspektivy razvitiia, ed. S.I. Bogdanov and E.V. Khvorost’ianova (St. Petersburg: Filologicheskii fakul’tet Sankt-Peterburgskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta). Pp. 386–97.

Khvorost’ianova, E.V., comp. 2003. “Perepiska K. F. Taranovskogo s V. E. Kholshevnikovym.” Acta Linguistica Petropolitana, vol. 1, part 3, pp. 311–74.

Kolmogorov, A.N. and A.V. Prokhorov. 2015. “Statisticheskie metody issledovaniia ritma stikhotvornoi rechi. Opyt rascheta i sravneniia modelei ritma.” In A.N. Kolmogorov. Trudy po stikhovedeniiu (Moscow: Moskovskii tsentr nepreryvnogo matematicheskogo obrazovaniia). Pp. 181–214.

Kovaleva, T.V. 1994. Spravochnye materialy k spetsseminaru “Russkii stikh XIX–XX vekov”. (Orel: Orlovskii gosudarstvennyi pedagogicheskii insitut).

Liapin, Sergei. 2019. “Rhythmical Structure of Russian Iambic Tetrameter and Its Evolution.” In Quantitative Approaches to Versification, ed. Petr Plecháč et al. ([Prague]: Institute of Czech Literature, Czech Academy of Sciences). Pp. 125–30.

Pilshchikov, Igor. 2019. “Rhythmically Ambiguous Words or Rhythmically Ambiguous Lines? In Search of New Approaches to an Analysis of the Rhythmic Varieties of Syllabic-Accentual Meters.” In Quantitative Approaches to Versification, ed. Petr Plecháč et al. ([Prague]: Institute of Czech Literature, Czech Academy of Sciences). Pp. 193–200.

Scherr, Barry P. 1986. Russian Poetry: Meter, Rhythm and Rhyme (Berkeley: University of California Press).

Scherr, Barry P. 2014. “Taranovsky’s Laws: Further Observations from a Comparative Perspective.” In Poetry and Poetics: A Centennial Tribute to Kiril ←28 | 29→Taranovsky, ed. Barry P. Scherr, James Bailey and Vida T. Johnson (Bloomington, IN: Slavica). Pp. 343–63.

Shapir, Maksim. 2005. “ ‘Tebe chisla i mery net’: O vozmozhnostiakh i granitsakh ‘tochnykh metodov’ v gumanitarnykh naukakh.” Voprosy Iazykoznaniia, 54, no. 1, 43–62.

Shengeli, Georgii. 1923. Traktat o russkom stikhe: Chast’ pervaia. Organicheskaia metrika. 2nd. ed. rev. (Moscow and Leningrad: GIKhL).

Smith, G.S. 1980. “Stanza Rhythm and Stress Load in the Iambic Tetrameter of V.F. Xodasevič.” Slavic and East European Journal 24, no. 1, 25–36.

Struve, Gleb. 1968. “Some Observations on Pasternak’s Ternary Metres.” In Studies in Slavic Linguistics and Poetics in Honor of Boris O. Unbegaun, ed. Robert Magidoff et al. (New York: New York University Press). Pp. 227–44.

Taranovsky, Kiril. 1953. Ruski dvodelni ritmovi, I-II. Monograph Series, Serbian Academy of Sciences, no. 217: Language and Literature Section, vol. 5. (Belgrade: Naučna knjiga).

Taranovsky, Kiril. 2000. “Chetyrekhstopnyi iamb Andreia Belogo.” In his O poezii i poetike. (Moscow: Iazyki russkoi kul’tury). Pp. 300–18.

Taranovsky, Kiril. 2010. “Russkie dvuslozhnye razmery.” In his Russkie dvuslozhnye razmery. Stat’i o stikhe (Moscow: Iazyki slavianskoi kul’tury). Pp. 11–363.

Taranovsky, Kiril. 2010a. “Russkii chetyrekhstopnyi iamb dvukh pervykh desiatiletii XX veka.” In his Russkie dvuslozhnye razmery. Stat’i o stikhe (Moscow: Iazyki slavianskoi kul’tury). Pp. 367–397.

Tomashevskii, B.V. 1929. O stikhe (Leningrad: Priboi).

Wachtel, Michael. 2015. “Charts, Graphs, and Meaning: Kiril Taranovsky and the Study of Russian Versification.” Slavic and East European Journal, 59, no. 2, 178–93.

Zhirmunskii, V.M. 1925. Vvedenie v metriku (Leningrad: Academia).

Zhirmunskii, V.M. 1968. “O natsional’nykh formakh iambicheskogo stikha.” In Teoriia sikha, ed. V.E. Kholshevnikov, D.S. Likhachev, and V.M. Zhirmunskii (Leningrad: Nauka). Pp. 7–23.

Zhirmunskii, V.M. 1974. “K voprosu o stikhotvornom ritme.” In Istoriko–filologicheskie issledovaniia: Sbornik statei pamiati akademika N.I. Konrada, ed. B.G. Gafurov (Moscow: Nauka). Pp. 27–37.

←29 | 30→←30 | 31→1 I wish to express my thanks to Igor Pilshchikov for conversations that have helped shape my thinking about topics treated in this article.

2 For a brief history, see Scherr 1986: 47–50.

3 When the original Serbian version of Taranovsky’s book was being translated into English in 1970–71, he expressed hesitation about seeing his old study remain in its original form, even stating that it would have been desirable to rewrite the entire work (Wachtel 2015: 189–190 [note 20]). As the 1969 letter quoted below indicates, his thinking about certain matters had evolved, and he was also aware that he needed to expand the research into some of the forms he had discussed. Be that as it may, he seems never to have attempted a revision. The English translation remains published.

4 Taranovsky’s letter, which occupies ten printed pages, required the compiler to supply some 80 footnotes. The document is very much worth reading in its entirety for Taranovsky’s informal but penetrating observations on a number of issues (Khvorost’ianova 2003: 315–32).

5 This observation is based on the research of Georgii Shengeli, who examined 50,000 words in prose excerpts (5000 words from each of 10 writers, ranging from Pushkin to Belyi) and presented his findings in a detailed table (1923: 20–21). He regarded proclitics and enclitics as part of a word, so that «и пошел бы» counts as a single four-syllable word. His main overall finding was that stress has a strong tendency to appear toward the center of a word, with a weaker tendency to “lean” toward the end. Thus in 3-syllable words the stress occurs on the middle syllable nearly half the time, while the third syllable is stressed about 20 % more often than the first. Roughly 7/8 of four-syllable words are stressed on one of the middle two syllables, with the third syllable stressed more often than the second – and the fourth more often than the first.

6 As Taranovsky points out in this article, “in no previous period did individual poets differ so sharply from each other in their structure of iambic tetrameter verse as in the first two decades of the twentieth century” (2010a: 389). Indeed, for many of the poets he discusses, the binary structure of the verse line (with strong second and fourth ictuses), which characterized the use of that meter over much of the nineteenth century, disappears and is often replaced by a rhythm more typical of the eighteenth or very early nineteenth centuries. (Those consulting this Russian translation of his article should be aware that Table 15, meant to show Gumilev’s practice, mistakenly reproduces the figures from Table 13 [383–84] however, the correct percentages for Gumilev can be found in the summary table at the end of the article [396–97].)

7 Gasparov here quotes the epigraph («Третий сорт ничуть не хуже первого») to Kornei Chukovskii’s well-known article «Третий сорт» (Chukovskii 2002). The phrase had appeared in an advertisement.

8 Taranovsky, in Table IV, also presents figures gleaned from Belyi, who looked at several poets active later in the nineteenth century. However, by far the bulk of the data in the three tables relates to earlier periods.

9 Compare Liapin’s overall percentages for stressing on the strong positions in the poems he examines (81.6 / 84.3 / 49.9 / 100) (2019: 127) with, for instance, those that Taranovsky provides for Blok’s lyric poetry of 1907-16 (83.7 / 85.5 / 52.0 / 100) or for the first part of “Vozmezdie” (81.8 / 84.5 / 46.3 / 100) ( (2010a: 376). As for the late nineteenth century, Tatiana Kovaleva has provided data—albeit without distinguishing between narrative and lyric verse—for the rhythm employed by a wide range of poets in the 1880s and 1890s; several use a rhythm resembling that found by Liapin in narrative verse (Kovaleva 1994: 49 [Table 48]).

10 For the first of the half dozen lines from Evgenii Onegin that Zhirmunsky analyzes – Минуты две они молчали – he lists the stressing as 2-3, 1-3. The hyphens are used to indicate words that are closely linked.

11 Interestingly, the journal asked Zhirmunsky himself to referee the article. While suggesting some revisions, he gave the piece a positive recommendation. (Baevskii 2007: 138–39).

12 In the course of a study devoted to the different topic of stanza rhythm, G.S. Smith (1980) conveyed precisely this information about the works he was examining. His detailed presentation dealt first with the overall stressing in poems by Khodasevich, went on to list the distribution of light and heavy stresses on the ictuses, and finally gave the numbers of light and strong hypermetrical stresses on each line of the stanza.

Again on Bakhtin and Poetry, with a Very Long Preface on the Perfidious Cult

Caryl Emerson

Princеton University

The year 2020: the boom is long over. Bakhtin’s name is now an adjective with the ring of a sedate global classic. The terms carnival, dialogue, polyphony, and chronotope no longer need attribution. The nasty squabbles and turf wars of the 1980s – 90s have either faded away or been resolved. The seven-volume Collected Works of Bakhtin in Russian (1996–2012) contains as many pages of rough drafts and commentary as it does published texts. Today we know that Bakhtin was never a Marxist; that he was an Orthodox believer but that his ideas need not be grounded there; that he was unapologetically a philosopher-thinker first and a literary critic by default (like Leo Tolstoy, Bakhtin raided literature – albeit often brilliantly – in support of his worldview, rather than analyze it on its own terms). We also know that he was a bit of a trickster, who both did and did not write books for his friends and who borrowed parts of his CV from his elder brother (although these acts too had their reasons). The Bakhtin cult is over as well. Lidia Ginzburg was surprised in the 1980s that a ‘Society’ had been founded in the West devoted to such eccentric, imprecise literary ideas as Bakhtin had professed on Dostoevsky and Rabelais; her voice is no longer alone. A principled case against Bakhtinian method has been made by several scholars of high repute, including the great philologist and verse scholar Mikhail Gasparov, and (from another angle) the Byzantinist Sergei Averintsev.

1. The de-crowning (but not carnivalized) biographical word

The honoree of this volume, Michael Wachtel, has long been a skeptical other to Bakhtin, serving the Gasparov side of their agon.1 The Gasparovite critique ←31 | 32→is very robust. Beginning in the 1970s and lasting up until the year of his death, Gasparov argued with increasing vigor that all talk of a “living dialogue” inside a work of art, or between reader and verbal text, is scholarly malpractice: lazy, solipsistic, egocentric, and as a research method disastrous, an act of aggression against aesthetic signs meticulously fixed in place by an author. Relations with a past culture are delicate and difficult, Gasparov insisted. To establish them properly we need training and effacement, an emptying out of our own intent. But the democratic Bakhtin makes these “discussions” seem easy and pleasant. If a text is sufficiently porous (as the best, truest novels are supposed to be), then anyone can walk into them, start talking, and expect to be heard. Resisting this comfortable dialogism, Gasparov stood for the hard-edged, alien, honestly recuperated poetic word. When literary specialists refuse to respect historical distance and radical cultural difference, he said, when they start “talking” with authors or begin to see and hear a “living other” on the page, they cease to be philologists.

Michael and I, colleagues in a small department, have had our own long history over the poetic and prosaic sides of the Russian literary tradition. The Preface to his Cambridge Introduction to Russian Poetry (2004) begins with the following provocative Gasparovite sentence, which I had to force myself not to take personally: “The achievements of Dostoevsky and Tolstoy notwithstanding, Russian literature is a tradition of poetry, and Russian readers have always recognized it as such.”2 Yet even as a prosaicist and old Bakhtin hand, and even granted that novels and poetry are processed differently, I have always found Gasparov’s criticisms extremely persuasive.3 Thanks largely to him, we have come to expect high-level rebuttal of Bakhtin’s ideas and methods, sensible correctives to their over-application, and prudent reasons to trim back the cult around his name.4 It was thus a surprise when, in 2017, a milestone in the domestic backlash against Bakhtin materialized in a substantial (400-page) biography of him by Aleksei Korovashko, b. 1970, in the venerable Russian series ‘Lives of Remarkable ←32 | 33→People’.5 Lashing out against both boom and cult, Korovashko begins his book by comparing the obligatory citing of Bakhtin today with the obligatory Marx-and-Engels references in Russia of yore: because of this adulation, and because of his trickster-subject, “a biography of Mikhail Bakhtin will not fit into the canon of classic life-writing. By its structure, such a biography more recalls a mythological novel about a dying and resurrecting ‘god’ of the humanities than it does a strictly documented story of the earthly fate of a person who really existed” (p. 6). Korovashko then proceeds to deconstruct what he considers to be this myth, not granting the mortal man any quarter of flexibility, compassion, or kindness.

In choosing his consultants, Korovashko avoids the disciples, preferring more ‘objective’ onlookers – and, of course, the documented record, selectively cited and offered in a chatty, cynical, bantering register.6 The one thing that Korovashko cannot tolerate is any reverence or piety toward his subject. Before the Revolution, Mikhail Mikhailovich was completely in the shadow of his brilliant elder brother Nikolai. Bakhtin the younger had trouble keeping up in school. He graduated from no institution of higher learning. No one noticed him as he scribbled away in isolation. True, Bakhtin had a devoted following in his teachers’ college in provincial Saransk, but look at the median norm: uneducated students, a wholly naïve professoriat. His wife, the one indispensable ‘other’ whose constant ministrations assured Bakhtin’s survival for half-a-century, is allotted only a single page, and even this profile is glossed by a devoted student’s comment ←33 | 34→rendered faintly derogatory in Korovashko’s use of it. Elena Aleksandrovna had a face “like a Madonna on an icon,” Rakhil Mirkina recalls, she knew her Mishuk was a “great man,” her life was “entirely dissolved in her husband’s, whose scholarly interests she placed higher than any interests of her own” (114).

Korovashko does note Bakhtin’s courage living with chronic illness, and credits him with the occasional confused insight about literature and existential Being. But we are reminded that Camus, Sartre, Barthes and Hannah Arendt said it better (149). Arrest, interrogation, and internal exile were not pleasant – but six years in Kustanai, Kazakhstan, weren’t nearly as bad as Alexander Menshikov’s banishment to Berеzovo in 1727, even if worse than some temporary demotion to a provincial institute in Soviet times (295). It was a good thing that Bakhtin abandoned his early philosophical ruminations, since his “brainstorming the bastions” in search of new foundations for the act or deed [поступок] hadn’t come off (212). Curiously, and against the grain of most critics, Korovashko sees no inconsistency in Bakhtin’s creative trajectory. The Dostoevsky book repeats the weaknesses of the early manuscripts; the essays on the novel push the same concepts further (267). Capricious titles and subtitles remind us that none of these ideas need be taken too seriously, as in fact his contemporaries wisely did not: «Если рукописи не сгорают, их эксгумируют» [If manuscripts don’t burn, then they are exhumed] (118, on the early notebooks); «Циклоп полифон, или как нам уконтрапунктить Достоевского» [The Cyclops Polyphonus, or how we ought to go about counterpointing Dostoevsky to death] «Хождение провинциального учителя по издательствам мукам» [A provincial teacher’s Road to publishing-house Calvary] (321, on Bakhtin’s futile pursuit of the interested publisher). Since Korovashko is not qualified to expand upon or critique the intellectual content of the Bakhtin corpus, however, he is reduced to paraphrasing portions of it vaguely, over hundreds of pages – an unhappy strategy, it turns out, because entirely devoid of narrative traction. If this is to be a biographical novel, then it must be written at least as tightly and effectively as the myth. And the author must be in control of his material.

But more is at stake. I have included this very long preface on the most recent biographical attack on the Bakhtin Cult in part because Michael Wachtel, too, has been at work for years on a biography. It is the life of Bakhtin’s favorite twentieth-century poet, Vyacheslav Ivanov, and I always beg to see the emerging chapters. The behavior of Ivanov, like that of Bakhtin, was very often passing strange. Having a child by his own stepdaughter (an act authorized in a vision from beyond the grave by her mother, Ivanov’s deceased wife) is only the tip of the iceberg. But these events, woven into a creative life, are presented by Michael Wachtel with a sort of tolerant wonder, a sense that the biographical subject ←34 | 35→being written up is a figure who merits his time and synthesizing energy. Reading Korovashko, one is struck by the vulnerability of any biographer who does not like his subject, who is neither interested in the subject’s ideas nor considers them worthy of a life-story. No number of facts could please him, even if his grounding in philosophy were adequate to Bakhtin’s subject matter, because what he resists and resents in the fact that Mikhail Bakhtin is world famous – and this, of course, is not the fault of the biographical subject.7 Any synthesis achieved by a biographer with this motivation will be driven by de-maskings, debunkings, and the device of the humiliating exposé. And such a negating strategy, deployed to illuminate a singular life and thus by definition outside a carnival economy, can only take away, not deepen. It is helpless to activate a consciousness from the inside (a Bakhtinian insight), and thus the biography, regardless of its truths, quickly becomes dead and thin. Only very gifted satirists can sustain disrespect over the long term. For all his presentation of Bakhtin as a trickster and a rogue, Korovashko approaches his subject with none of the light touch and two-way laughter of a carnival worldview. His style is heavy, sarcastic, morose. But one side effect of this deconstructive strategy, surely unintended by Korovashko, was to create a Bakhtin far tougher and shrewder, far more doggedly ambitious and less a victim and martyr, than the image produced by the boom and the cult. And this resonates with Bakhtin’s own self-image. By nature a sanguine and grateful personality, Bakhtin was alien to the pieties of victimhood. He considered his very survival to be a carnivalized event, a piece of wholly undeserved good fortune.

Perhaps by its very brashness, or because its pasquinades require so little work from the reader, this ZhZL biography caused a stir. It was long-listed for the 2018 ‘Big Book’ [Большая книга] national literary award. Korovashko’s website features interviews where he discusses frankly his disgust for the ←35 | 36→“Bakhtin-and-fill-in-the-blank” [Бахтин и имярек] methodology of global literary fads, however tempting that habit is with so “provocatively imprecise” a thinker as Bakhtin.8 Loyal Russian Bakhtinians, in turn, condemned the ZhZL volume as a scandalous postmodernist parody on a biography, devoid of archival research, intimate knowledge of the corpus, familiarity with historical details, literacy in educated Russian written style, and an even minimal respect for its subject.9 We will return to Korovashko’s approach to the problem of Bakhtin and poetry at the end of this essay. But first to review the state of that question.

2. The abused and embattled poetic word

For all the recent demystifications and deconstructions, serious questions remain about Bakhtin’s legacy that transcend the politicized, ideologized contexts of his (and our) times. One is the relationship of dialogue to carnival. Is the double-bodied image of carnival compatible with the double-voiced word of dialogue, or are carnival bodies – faceless, eyeless, often wordless – of a wholly different substance and value? Another unresolved question is the purported universality of Bakhtin’s categories and catchwords. He has now been translated into many dozens of languages, and societies devoted to his work hold symposia in all corners of the globe (the 16th International Bakhtin Conference was held in 2017 in Shanghai). But can this body of humanistic thought, the unapologetic product of one Russian thinker turning an irreverent lens on ancient Graeco-Roman culture and filtering his findings through German Romantic philosophy, be made relevant to all cultures of the world? Can this thought be essentialized in anything like a pan-human way? A third set of questions, suited to the honoree of this volume, is more formal: what lies at the base of Bakhtin’s purported dislike of poetry? As one pioneer on this topic, Donald Wesling, argued in 2003: literary ←36 | 37→scholars who care about verse must “rescue poetry from Bakhtin’s stingy and grumbling description of it.”10

For most readers of Bakhtin, this grumbling is loudest in the mid-career text known in English as “Discourse in the Novel” [«Слово в романе», 1934–36].11 As Clare Cavanagh underscores in a 1997 SEEJ forum on Bakhtinian ‘prosaics’, that rambling, far-reaching essay is where Bakhtin “turns lyric poetry into the straight man or fall guy for his properly ‘dialogic’ hero, prose fiction, or more precisely, the novel.”12 In Bakhtin’s rhetorical binary, the novelistic word is dialogic, dynamic, outward-facing, freedom-bearing, curious about others, and thus healthy for mind and spirit. The poetic word, in contrast, is monologic, possessive, inward-looking, anti-social and faintly tyrannical. Or at least this is true for “genres that are poetic in the narrow sense” (DiN 284/38). In his 2002 essay “Bakhtin and Poetry,” Michael Eskin observes that Bakhtin uses the word “poetry” [поэзия, поэтические жанры] in several senses.13 At times it refers to all fictive literary or poetic genres, as in the German Dichtung. At other times it marks any mode of speech that is highly organized (metrically, rhythmically, phonologically) and set off from everyday communication. And then Bakhtin often intends the meaning prevalent in early 20th century Russian culture: lyric verse that presumes the private, emotionalized, highly personal and unmediated expression of the author. The “narrow sense” would seem to cover poetry of the last two sorts. Here is Bakhtin’s case against it.

←37 | 38→In a poem, Bakhtin argues, the word’s “natural dialogicity is not put to artistic use” because poetry “is self-sufficient and does not presume any utterances by others beyond its borders” (DiN 285/38). If a poet is open to other utterances – the heteroglossia of the epoch – then personal poetic style is destroyed; this is because a poet’s language belongs wholly to the poet and reflects the author “directly and without mediation, without conditions and without distance” (285/39). Of course poets, like everyone else, are surrounded by other people’s words – and these words cannot be wholly shut out of their compositions. But inside a poem, this heteroglossia will sound like the utterances of characters, not of the poet; it will feel like an inserted thing (287/40). In fact, recalling the Symbolist and Futurist poets of his own generation, Bakhtin remarks that a poet “will sooner dream about the artificial creation of a new language specifically for poetry than he will exploit actual available social dialects” (287/40). This poetic appetite for artifice, stylistic unity, and restricted-access communication is then vaguely associated with authoritarianism and politically repressive power [власть], which Bakhtin juxtaposes to the prosy masks and messy pranks of jesters, fools, and rogues. (We must assume that if these jesters and rogues speak in intricate rhythmic and metric constructions – which is routine for comic folk genres – then the “repressive” constraints of literary form are somehow overridden by the boldness and powerlessness of the speaker.) At this point in his argument Bakhtin adds a footnote, to the effect that everywhere he is advancing as typical “the extreme ideal limit to which poetic genres aspire” – and of course existing poetic works contain many features of prose; in fact, hybrid variants are the norm (287/40). But this note is often ignored, because so much is unsatisfactory about Bakhtin’s entire framework. And it rankles. Prominent humanist scholars from Russian and English departments alike, smitten by the potential of dialogism, have tried for years to make sense out Bakhtin’s position on poetry, or at least to lessen its outrageousness.

One route of poetry-lovers has been to defend certain types of poetry (usually what they have worked on all their lives) and show how the parameters Bakhtin appears to reject are in fact the core and cornerstone of the whole. Donald Wesling, in his book on the social moorings of poetry mentioned above, accomplishes this by analyzing dialect poetry, and by bypassing formal versification in favor of “rhythmic cognition in the reader” (his exemplars include Marina Tsvetaeva and William Blake). In his “Afterward: One More Thing I know about Bakhtin,” Wesling summarizes the task of his book as the building of a “poetics of utterance… that is social in the direct sense.”14 This creation of ←38 | 39→a communally inflected poetics of utterance, interactive and integrated into the teaching of poetry as a crucial part of the literary humanities, has been pursued for two decades by another devoted Bakhtinian convert from the ranks of academic English, Don Bialostosky. A specialist on the English Romantic poets, Bialostosky has written three books under the star of Bakhtin. The design of the first, Wordsworth, Dialogics, and the Practice of Criticism (1992),15 resembles Wesling’s “social moorings”: a series of close readings demonstrating that the “Dialogics of the lyric” (the title of Bialostosky’s Chapter 4) is not some crimped oxymoron but a potent energy source. Bialostosky’s next book draws on an increasing fund of Bakhtin in English to embrace another mission dear to his heart: the restoration of a classical rhetorical tradition (elocution, delivery, diction and creative performance) to the classroom.16 It begins by reminding us that Bakhtin began as a classicist – albeit a rebellious one. His discourse theory, and that of his Circle, sooner re-writes and extends Aristotle’s Poetics than destroys it (122). But academic humanists today, in their quest for a literary science, have unnecessarily narrowed the classical legacy. Narratology has not benefited from its naively Aristotelian emphasis on plot (that is, dramatic showing rather than telling), just as “studies of lyric poetry have been blinded by formalist appropriations of Aristotle’s account of diction as [mere] material” (145). Bialostosky’s last book, How to Play a Poem (1917), is the most eloquent ‘applied Bakhtin’ to date in English from a poetry professional devoted to the art of teaching poetic form.17 Everything that Bakhtin in the 1930s suggested “poetry in the narrow sense” could not do, Bialostosky shows it can – and in fact, he shows it can be done better than anything we might expect from the private, lonely, isolated and silent experience of reading novels.

There are also poetry experts among Slavists who have taken up the revisionary cause, provocatively broadening the horizon from individual poets and texts to whole modes of thinking. In 1997, David Bethea contrasted the open ‘prosaic’ values of Bakhtin with the more closed and code-friendly ‘poetic thinking’ of Yuri Lotman, focusing on the latter’s thought as it evolved in the 1980s.18 The specific Bakhtinian value that Bethea singles out is the “uniquely ←39 | 40→specific and unexplicatable nature of an utterance” (3) – a bias that is fatal, it would seem, for the repetitions or patternings essential to poetry. But Lotman could bend and learn. While code, model, and structure remained precious concepts to him (and to his research subjects, Karamazin and Pushkin), Bethea properly concludes that because “Lotman was less of a speculative phenomenologist with one powerful idea (history’s drive toward novelization) and more of a pragmatic ‘enlightener’ and scientific thinker, he could in a way utterly alien to Bakhtin […] ‘loosen up,’ ‘organize’ his original Saussurean stance” (4–5). In the early 1990s Olga Sedakova, a great practicing Russian poet, reinforced Bethea’s insight about Bakhtin as a thinker with ‘one powerful idea’. “Bakhtin’s works record the experience of one idea,” Sedakova writes. “This idea concerns neither poetics nor literature in general, nor does it concern language” (89).19 Bakhtin never states it outright. As Sedakova sees it, the idea is contained in the contra-Sartrean moral-spiritual postulate that ‘Salvation is the Other’ – with the logical corollary that ‘I’ am fluid, prone to sin and wholly helpless whereas the Other is wholly enabled. Removed from its Symbolist-era context, however, and expected to answer for all the “words wrung from this idea” (such words as polyphony and ambivalence), Bakhtin’s matrix of values has been misunderstood. Poetry is assigned a transitional, unstable role in this value system, related to the powerful collective voice of the ancient chorus or Choir. “Bakhtin’s relationship to poetry (the lyric) depends on the extent of the gap between I and Him” (90), that is, between my lack of self-sufficiency and the Other’s ability to remedy that lack. Since Bakhtin continues throughout his life to define the ‘I’ only negatively, never coincident with its own place, the Other comes to be felt as its oppressive opponent, as a depersonalized force preventing my own consolidation, as undesirable ‘congealed forms of culture’ that close down rather than open up. The only way out of this trap is to laugh, but Sedakova does not welcome this route. In carnival, “the ‘intentional’ and the ‘choral’ word turns into the ‘authoritarian word’, and “the lyric disappears from the field of vision” (91).