The Fractured Self

Selected German Letters of the Australian-born Violinist Alma Moodie, 1918–1943

Summary

Australian-born, Moodie gives voice to the vulnerabilities of her position, living alone and constantly on tour as an unaccompanied, female virtuoso. She describes the profound satisfactions of her career triumphs, the joys and tensions of her marriage and her deep love for her children. Weaving through the narrative is the miracle of her ability as a virtuoso violinist, an ability that commanded the admiration and respect of many of the leading cultural figures of the day. Famous conductors, prominent musicians, contemporary composers, writers and art connoisseurs all fell under the spell of her sensational playing and lively personality.

Originally written in three languages, the letters are made available here for the first time in English translation. Extensive annotations place the letters in their historical context while short essays by specialists in their fields reflect on particular themes.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

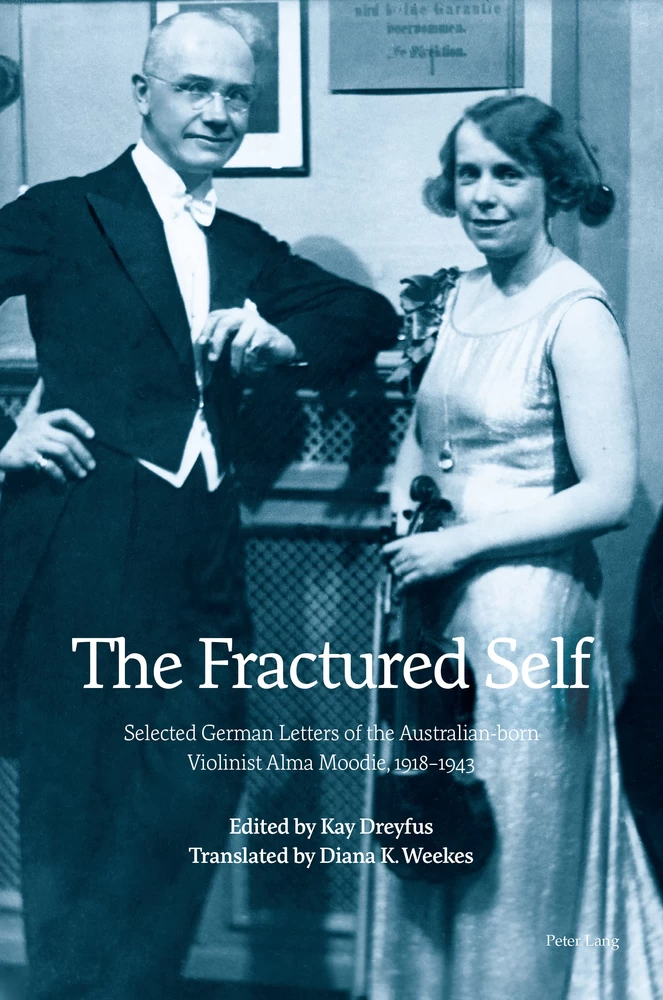

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Editor’s Introduction and Note (Kay Dreyfus)

- Translator’s Note (Diana K. Weekes)

- List of Abbreviations

- The Letters

- Part One: Starting Over 1918–1923: Letters 1–46

- Part Two: Complications and Resolutions 1924–1928: Letters 47–148

- Part Three: Years of Crisis and Fulfilment 1929–1932: Letters 149–185

- Part Four: Uneasy Accommodations 1933–1938: Letters 186–231

- Part Five: War and Death 1939–1943: Letters 232–268

- Addenda: Letters 269–270

- Reflections

- Einige Erinnerungen an Alma Moodies Künstlerschaft [Some Memories of Alma Moodie’s Artistry] (Eduard Erdmann)

- On the Higher Values of Artistic Personality: Alma Moodie’s Path in Response to Carl Flesch (Goetz Richter)

- Alma Moodie as Eduard Erdmann’s Chamber Music Partner (Birgit Saak (transl. diana k. weekes))

- Moodie and Krenek: Challenging Ernst’s Ernestness (Peter Tregear)

- Alma Moodie and the Third Reich (Michael Haas)

- Endnotes

- Select Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors

- Index of Recipients

- General Index

Illustrations

Group 1

1.Artur Schnabel (seated) and Carl Flesch, Berlin, 1882

2.Moodie’s Australian family, n.d. (c.1911)

3.Eduard and Irene Erdmann, 1919

4.Hans and Mimi Pfitzner with their children, 1921

5.Program, Moodie Erdmann recital, 1921

6.The first two pages from Moodie’s Letter to Werner Reinhart, “Bucarest, Mardi” (mid-January 1924)

7.Postcards to Irene and Eduard Erdmann

9.Eduard Erdmann, Teplitz-Schönau, c.1928

10.Moodie with her son, 16 October 1928

11.Five famous conductors at a reception for Arturo Toscanini, Berlin, c. 1929

Group 2

12.Postcards to Irene and Eduard Erdmann, 1929, 1941[?]

13.Werner Reinhart and Igor Stravinsky, 1930

17.Barbara Spengler, c. 9 months, 1932

18.Relaxing on the beach with Carl Flesch, n.d. (1930s)

19.Letter, Carl Flesch, Moodie and students to Hans Pfitzner, July 1933

21.Letter, Alma Moodie to Berta Volmer, n.d. (late 1936)←ix | x→

22.Eduard Erdmann and his children, 1937

Acknowledgements

I have incurred many obligations over the course of my several decades of research into the life and career of Alma Moodie. In connection with this present book, my first thanks go to those institutions and individuals who have given me permission to publish Moodie’s letters: Akademie der Künste, Berlin: Musikarchiv (letters to Eduard and Irene Erdmann and Artur Schnabel); Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach (letters to Theodora von der Mühll and Anton Kippenberg); Paul Erdmann (Erdmann memorial essay); Matthias Gräff-Schestag (letters to Lotte Seeger); Musik- och teaterbiblioteket, Stockholm (letters to Kurt Atterberg); Musiksammlung der Östereichischen Nationalbibliothek (letters to Hans Pfitzner); Nederlands Muziek Institut, Den Haag (letters to Carl Flesch); Paul Sacher Stiftung (letters and telegram to Igor Stravinsky); State Library of Queensland (letters to Louis D’Hage); Professor Dr Werner Strik, Berne (letters to and from Rainer Maria Rilke); Universität der Künste, Berlin: Universitätsarchiv (letters to the Hochschule für Musik and Max Rostal); Suzan White (letters to the Moodie aunts); Winterthurer Bibliotheken, Sammlung Winterthur and Musikkollegium Winterthur (letters to Werner Reinhart and Georg Reinhart). Special thanks are due to the librarians in these various institutions, and to other custodians of Moodie’s letters, for providing me with copies and responding to my queries and requests with unfailing courtesy. Amongst these I would particularly like to mention Dr Werner Grünzweig and Frau Anouk Jeschke (AdKB), Frau Antje Kalcher (UdKB), Dr Andrea Harrandt (ÖNB), Frau Regula Geiser (winbib) and Dr Gertrud Muraro (MKW).

Acknowledgments for the use of images may be found in the individual captions.

Other helpful individuals to whom my thanks are due: Professor Kerry Murphy (for assistance with French texts); Dr Leo Kretzenbacher and Christa Rumsey (for assistance with German texts); Dr Janet Kirkconnell ←xi | xii→(for providing copies of Moodie’s letters to Berta Volmer and information about the Beredin string quartet); Jackie Waylen (specialist subject librarian for music, theatre and performance at Monash University, for unstinting research support); Dr Shoshana Dreyfus (for endless conversations and specialist linguistic advice on Moodie’s language mixing); Dr Florian Gelzer (for a generous exchange of ideas and information about the Moodie/Rilke letters); and Dr Tatjana Goldberg (for her unswerving faith in the importance of the project). I am specially grateful to Dr Birgit Saak for her generosity in sharing her transcriptions of the Moodie-Erdmann correspondence and Erdmann’s memorial essay.

My thanks go to the specialist contributors whose reflections appear in the second part of the book.

Diana K. Weekes, my colleague and collaborator on this project, has been endlessly helpful and supportive. She not only undertook the massive task of transcribing the letters, translating Moodie’s non-English letters and checking the text as it took shape, but also advised on the final selection of letters and assisted speedily and generously with many other tasks of translation as requested. Diana would also like to acknowledge the unfailing interest, support and assistance of her late sister, Virginia Weekes.

We would like to thank the Mariann-Steegmann-Foundation (Switzerland) and the Marshall-Hall Trust (Melbourne) for their generous financial support. For administrative support in connection with the latter grant, we acknowledge Creative Partnerships Australia and the Australian Cultural Fund.Finally, our best thanks to Dr Laurel Plapp, Jaishree Thiyagarajan and the production team at Peter Lang Oxford for their work and care in turning a complex manuscript into a book.

Editor’s Introduction and Note

Alma Moodie was born in Mount Morgan, Central Queensland, in 1898. She left Australia in July 1907, three months before her ninth birthday, to study at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. Her first attempt to launch a career in Germany from late 1911 was thwarted by the outbreak of the First World War. As enemy aliens in Germany, she and her mother returned to Brussels, where her mother died of consumption in May 1918.

Moodie returned to Germany after the war as the ward of a German prince, undertook retraining as a violinist under Carl Flesch, the foremost German violin teacher of the day, and made a sensational debut in Berlin in November 1919. From that time onwards, until her untimely death in March 1943, she enjoyed a high reputation as a concert violinist, performing across Europe as a soloist with the principal orchestras and conductors, as a recitalist and (later) chamber music musician. Her musical talent was such that she attracted the attention of many leading contemporaneous personalities across the arts. In particular, the patronage and friendship of Werner Reinhart, a well-known Swiss businessman and philanthropist, gave her entrée to the top echelons of musical and cultural life. After that, her gift sustained the relationships that were formed, as she explained to her Rockhampton teacher Louis d’Hage in 1923:

Violin isn’t my only interest in life, & I don’t work to play publicly. I play only to be able to go on in what my real life is, & that consists in Art all round, pictures, architecture, litterature [sic], languages & my Interests bring me in contact with the leading people in the different branches & my Art is big & strong enough to enable me to give to them & I am working in my building[,] giving it a foundation that isn’t necessary but a great satisfaction to me.

She premiered many contemporary works including those of Stravinsky, Pfitzner, Hindemith, Krenek and others, several of which were written for and dedicated to her.

←xiii | xiv→Her career spans two of the most tumultuous decades of twentieth-century German history, and her letters reflect the impact of external events on the life of an individual involved in public life and subject to its vicissitudes. In particular, the letters chart her efforts to accommodate, as a working professional, the cultural policies of the Third Reich. By the thirties she was a German citizen by virtue of her marriage, but the fact that she was foreign-born and unable to validate her Aryan status places her in a group which, to date, has not received much attention from scholars of this period. I argue that her death, of accidental barbiturate poisoning, was the result of cumulative psychic fractures related to the moral and personal compromises forced upon her by her position and the circumstances of the regime and the war. These issues are refracted in her letters through the constraints of censorship as the 1930s progressed.

We have selected some 270 letters from among the c.500 that I have collected over the course of several decades. Her first surviving letters are those written in English to friends and family in Queensland from the day of her departure in 1907. But the present selection begins from the time of her return to Germany in 1918, since this was when her range of activities and acquaintance began to expand and her life as a musician to assume its permanent shape. It is very clear that Moodie wrote many more letters than have survived. In her letter to Werner Reinhart of 28 April 1924, for instance, she refers to her “formidable post” and many times she mentions spending a whole day on her letters. Much of her letter-writing would have been utilitarian in purpose, concerned with her travel, holiday, concert or rehearsal arrangements. Although she refers to a telephone as early as January 1921, her peripatetic lifestyle – about which Hans Pfitzner was to complain so bitterly in his letters to her from the early 1920s – made this form of communication difficult and she does not seem to have embraced it with any enthusiasm until the early 1930s. As she wrote to one correspondent, “Letters written to the Berlin address however always reach me”.

Moodie was unparented in Germany and her close family was in Australia. She had travelled to Brussels with her mother (her father died when she was 1 year old), but her mother’s death in May 1918 left her unchaperoned and alone. Despite her deep connection to the family of the Fürst [Prince] of Stolberg-Wernigerode, as whose ward she returned to ←xiv | xv→Germany in 1918, she speaks in her letters a number of times of the gap left by her mother’s death. The seemingly unrestrained frankness with which she discusses her innermost thoughts and feelings in some of her letters to her close friends – most notably but not exclusively Reinhart – bears witness to the paramount importance of friendship as the basis of her personal and professional security, at least until she married. Letter-writing anchored her emotional life, linked her to absent friends and enabled her – at least for the most part – to withstand the pressures of a relentlessly rootless professional life. For her, letter-writing was a fundamental mode of communication and the enjoyment of an accumulation of post was part of the pleasure of home-coming.

The selection of letters for this book has been shaped in the first instance by the accident of survival. Moodie’s constant travelling in the years before her marriage, her many changes of address, the destructive impact of the war, the circumstances of her death, and her husband’s wartime situation and post-war marriages all seem to have mitigated against the preservation of personal papers of any kind. The only letters to remain in her son’s keeping were those to and from Rainer Maria Rilke and, most affectingly, a final Abschiedsbrief to her husband.

Letters included here are mainly drawn from collections written to high-profile correspondents whose reputation was such as to invite conservation in public collections and whose action in keeping Moodie’s letters must surely work against any claim that she never imagined they would be read by anyone other than the person to whom they were written – always an ethical challenge for this kind of editorial project.1 Fortunately, these sequences happen to coincide with what were unquestionably important long-term relationships in her life. There are five principal recipients: Carl Flesch (violinist and violin pedagogue), Hans Pfitzner (composer), Werner Reinhart (musical amateur and patron of wide influence and interests), Eduard Erdmann (pianist, composer and Moodie’s long-time duo-recital partner) and Irene Erdmann (wife of Eduard and one of only three female correspondents for whom more than occasional letters have been located). There is a small but highly important series of letters to the poet Rainer Maria Rilke and a small, insightful group of letters written by Moodie in her role as a professor of violin to one of her students (late 1930s–early 1940s). ←xv | xvi→Especially noticeable is the lack of any letters to her husband, other than the one mentioned above that is Moodie’s last in the present selection, this despite his frequent absences from home.

It is immediately striking that most of these recipients are men, but this perhaps says less about Moodie herself than some might like to think. The world of music in the early twentieth century was, as she was very well aware, a man’s world. Of the two female correspondents included here, one is Erdmann’s wife and the other Moodie’s student. Her letters to these women, though fewer in number, allow us to glimpse a different side of her nature. Here is Moodie as wife, home-maker and mother, as caring teacher and sympathetic colleague and friend.

The selection is dominated by her letters to Werner Reinhart. The exact circumstances of their meeting are not known. But from the time of her first appearance as soloist with the Musikkollegium Winterthur in October 1922, when she stayed as Reinhart’s guest at Rychenberg, the Reinhart family villa in Winterthur, she wrote to him regularly, at least once a week, until her marriage in 1928. After that her letters became less frequent and more formal, though the abiding importance of his friendship was never in question.

Some two hundred letters survive from Moodie to Reinhart, written between October 1922 and 16 February 1943, of which we have included 136. Her last letter was sent on to Reinhart by Moodie’s husband some months after her death. Only five of Reinhart’s letters to Moodie remain as copies in Reinhart’s files, though it is clear from her responses that he wrote to her regularly, even if not quite as often as she to him. Unsurprisingly, those he kept are formal business letters concerning her performances with the Musikkollegium, Winterthur. Of the personal letters he wrote to her, none remain. We may only know about their relationship from what is reflected in her letters to him. It is a relationship that invites speculation.

Most writers position themselves in relation to the person being written to. In Moodie’s case this is very obvious and certainly deliberate, if not wholly conscious. Moodie’s letter-writing style defines her relationships in very particular and intimate ways. She was writing in two European languages in which there is a clear lexical and syntactic distinction between the formal (Sie/vous) and informal (Du/tu) modes of address, and strong ←xvi | xvii→social constraints inhibit the move to the informal mode. The first thirteen letters in this volume, all written in German, introduce some correspondents with whom she only communicated in that language. As several of these are either introductory (Flesch, Erdmann, Pfitzner) or gratitude letters (Atterberg), they are written in a careful, formal style, with due attention to handwriting and content. Writing to professional colleagues or to creative luminaries like Pfitzner and Rilke, she is clearly aware of age, social status or occupational hierarchy. Over time, her letters to people who became her friends took on a greater or lesser degree of informality and we may chart the development of intimacy in the relationships by changes in the salutation and in the shift from “Sie” to “Du”. This aspect of her letter-writing is discussed in more detail in the Translator’s Note and Birgit Saak’s note on Moodie’s vernacular language use in her letters to the Erdmanns.

From the beginning, her letters to Reinhart are striking for their mix of formality and intimacy. On the one hand, they never moved past the formal “Sie”, a feature perhaps more indicative of his reserve and need to preserve a particular public persona than a measure of the depth of feeling between them. On the other, especially in the early years of their friendship, she loved to address him with playful nicknames. A special favourite (always in English) was “Pussy” – an endearment of particular familiarity, which appears in various permutations in her letters from the 1920s, up to the point of the birth of her first child. In other sobriquets, such as “Prince”, “Indian Prince” or “marchand de coton”, we may catch echoes of Reinhart’s social status or professional interests. Yet others reveal aspects of their relationship: his gift to Moodie of her Gofriller violin produced “Guarnerio” or “Guarnerius”; her habit of weekly letter-writing yielded “Werner, my own Sunday day pet”. In general, she did not use his first name in her salutations and if, after her marriage, these settled to a habitual, English-language “Reinhart dear” and her language stabilised to German, there is no doubting her tenderness. Since Moodie’s salutations are so expressive of her mood and her relationships, we have left them as in the original letters.

Letters reflect her tri-lingual capabilities. In particular her early letters to Reinhart – who, as a Swiss with international mercantile interests, was himself tri-lingual – are written in a mixture of all three languages. ←xvii | xviii→Apart from her varied choice of a base language, she often employs all three in a single letter, sometimes shifting freely from one to another in mid-sentence – a practice known as code-mixing or code-switching. The Translator’s Note explains how we have represented these language shifts in our presentation of the translations. It is notable, however, that of the 136 letters to Reinhart, a significant number are written wholly or partly in English, including her very first, from October 1922. This choice of her mother-tongue, or indeed of her mother’s mother-tongue, combined with the introspective candour of the letters themselves, invites one to speculate that Reinhart fulfilled part of the role her mother would have played in her life. For Moodie, Reinhart was the trusted confidant who also, from time to time, rescued her financially, and whose long-established family home at Rychenberg gave her an experience of warmth and stability that was otherwise missing from her life, at least in the 1920s. Because of his own guardedness about the exact nature of their relationship, she could rely on him not to gossip – an activity greatly enjoyed by many of her other friends.

Moodie’s first language was English, though one can point to the fact that she only spoke English exclusively until she was about 8 years old, and after that probably only domestically with her mother until her mother’s death in 1918. She learnt French as her second language, but as a child, and would have spoken it in all situations outside the home from 1907 until she left Brussels in 1918. She acquired German as a third language, probably from as early as 1911 (when she was 13) and spoke German in her daily life for at least twenty-five years (1918–1943), as it was essential to her work and many of her lasting friendships were with exclusive German speakers. In certain situations (and countries) and with certain people (for example, Rainer Maria Rilke) she continued to speak French. Increasingly after her marriage in 1928 and as the Third Reich consolidated its control over German life through the 1930s and into the 1940s, German became her matrix language.

It is unlikely that she had much in the way of formal language instruction. Given that she left Australia before she was 9 years old, whatever schooling she received must have been short-term. In Brussels, her education focussed around her musical training, though her mother’s early letters home record that Alma was excused from certain classes and ←xviii | xix→lessons until she had learnt French, suggesting she may have had some tutoring in that language. Moodie’s informal French correspondence style, though extremely fluent and comfortable, has the character of everyday, colloquial French written down, with some grammatical errors that would not have been noticed when spoken. It is not surprising that this should be the case, as Moodie would have spoken French more than she wrote it. Similarly, she often uses colloquialisms in German that are not usually used in formal written language.

German-language letters comprise almost two-thirds of this selection; after 1935, she writes exclusively in German. Nonetheless it would be a mistake to claim that Moodie has a single base of language or discourse; she is what linguists would call a balanced or true tri-lingual. In her letters to Reinhart, she reaches for whatever word or phrase or colloquial expression in whatever language serves best to communicate her ideas, to enhance a letter’s expressive playfulness or lighten an otherwise serious topic. Except when she is writing carefully, style is not her first priority. She writes fluently and idiomatically, often at speed and without correction, with a fine flair for observation and description and a great sense of humour.

Irrespective of the language in which they are written, Moodie’s letters reflect the influence of cross-language interference – in spelling, grammar, vocabulary and word order. Accordingly, and quite apart from the interest of the circumstances in which the letters were written and the importance of the recipient, the letters have a distinctive charm and character.

A Note on Moodie’s English-Language Use

The letters testify to the fact that Moodie read widely in all three languages. This fact notwithstanding, her English spelling is occasionally idiosyncratic. Some words are never spelled correctly. To speak about her spelling mistakes as the product of incompetence, however, is to overlook the other insights they might offer into her language acquisition and creativity. Apparent “errors” can have more than one cause. She never grasped the use of the apostrophe in the possessive form, nor in common ←xix | xx→English contractions, possibly because she would not have seen these words written. She habitually writes “you’r” and “havn’t”. Her spelling provides several examples of code-mixing: she routinely spells “Adress” in English with one “d” (as in the German die Adresse); “nature” is always “natur” after the German (die Natur); “wonder” is often “wunder”/“wundering” (the German, “das Wunder”, intersects with the sound of the word in English). The Translator’s Note provides other examples of how language transfer or interference between German and English affected vocabulary and word order.

Her personal Anglicised version of several words owes something to the French: enthousiasm (enthousiasme), devellopment/ develloping (développement); responsable; envellope; litterature (littérature); caracter (caractère); comparasons (comparaison); principels (principes); catastrophy (catastrophe); circomstances (circonstances). Her use of the lower case for nationalities mirrors usage in both German and French: indian Princes; european kiss; greek Dictionaries; the dutch public; english books. At other times, her phonetic spelling invites speculation that as her English-language education was interrupted at an early age, her spelling remained caught at that point of language development known as invented or inventive spelling: hight; inclosed; intitled; rediculous/ridiculus (Fre. ridicule); squeel; leaveing; rehurse/rehursal and so forth. Two sets of words are consistently intriguing: she never mastered the spelling of adverbs with the “ly” suffix (terrificly; absolutly; entirly; intensly; definitly); words beginning with “de” she writes phonetically as “di” (dispair; dispise/dispisal; dicisive; discribing/discription). “Distain” appears to be her own invention. She often misspells or Anglicises German proper names. The spelling of the names of some European towns reflects historical variations as well as differences between English and original language forms.

Editorial Principles

In the English-language transcriptions, we have aimed to reproduce as faithfully as possible the content of each letter, including its punctuation, ←xx | xxi→spelling and format, with “[sic]” being added only when a word seems highly improbable. Her divergent spelling is not reproduced in the translations, and punctuation is standardised. The ampersand she favoured is left as she wrote it in her English text even when, as is sometimes the case, it starts a sentence. Ampersands and the German equivalent “u.” (und [and]) are written out in full in translation.

Some aspects of the layout of the letters have also been standardised. The form of the addresses and dates is as she wrote them, but they are placed to the left of the page. We have not replicated Moodie’s practice of underlining the name of the town from which her letter was written. Small caps in the address indicates her use of letter-headed notepaper. The original language of each letter is indicated at the start. Where letters were written in a mixture of languages, these are shown in a descending order of quantitative importance. In the text of the letters, italics are used to show language shifts (to French or German in English-language letters; to English in French- or German-language letters). Italics also replace the underlining Moodie used for emphasis. There are instances where these two usages coincide; we rely on context to make the difference clear.

Postscripts and afterthoughts, wherever they appear in the manuscript, are placed after the signature. We have made some assumptions about paragraphing in both the English transcriptions and the translations, as Moodie’s paragraphing is erratic and her text sometimes continues for several pages without a break. Like many of her generation, Moodie favoured the dash above other punctuation marks so that occasionally, for the sake of clarity, we have had to intervene. We have kept her parenthetical dashes, but in cases where a dash seems no more than a hasty swipe of the pen, we have substituted orthodox punctuation marks.

In annotating the letters, I have sought to capture the many reverberations of Moodie’s text, the richness of the musical and cultural milieu in which she lived and worked, along with its sometimes less obvious personal, social and political pressures. As we are presenting the letters in English translation, the explanatory annotations are targeted at readers for whom people and events referred to may not be familiar. The annotations aim to identify personalities and clarify allusions with a primary emphasis on Moodie’s relationship to the subject of the note. Some obvious references ←xxi | xxii→have been taken for granted, such as her canonic reading or familiar musical compositions. Allusions that I have been unable to elucidate, such as the identity of less well-known members of Reinhart’s social circle, are acknowledged.

The ready availability of information on the internet presents a challenge to the convention of providing explanatory notes in a book of this kind, especially biographical ones. We have deployed the brief biographical sketches to two ends. Firstly, to demonstrate the range of Moodie’s personal acquaintance, social, cultural, musical and political. By populating her professional milieu with some of the great names of the period, we show the level at which she herself was working and the reputation she enjoyed. After 1933, however, many individuals were confronted with a need to make life-changing choices. By assimilating into the narrative of her life a brief account of the fateful decisions made by so many of Moodie’s friends and colleagues, we show, at least by inference, their impact on her. She was to write in 1940, “with these apocalyptic events, the fate of individuals concerns me greatly” (see letter 243). What did she feel, through that last decade of her life, as close associates disappeared?

In place of a formal editor’s introduction, I have commissioned four short essays reflecting on specific themes by specialists in their fields. This may be a rather unorthodox approach, but has the value of showing how the letters open out onto themes of broader personal, social and musical significance. We have also included, in English translation, the text of an unpublished memorial essay written shortly after Moodie’s death by her long-term recital partner Eduard Erdmann, which offers an intimate and comprehensive account of Moodie’s artistic personality and development.

– Kay Dreyfus

Translator’s Note

The first challenge in translating Alma Moodie’s German correspondence was her unusually strong, loopy hand-writing, in which i’s and e’s looked very much alike, n’s, m’s and u’s were almost inseparable and it was relatively easy to stumble over words like annimmt (from annehmen, meaning to “accept”, “take”, “assume”, “embrace”, or “approve”). Furthermore, because it was also large and took up so much space on the page (as she herself admitted), she often made use of the narrowest margins to finish a word or sentence so that at the end of a line, characters could be squeezed so tightly together as to be almost indistinguishable. Post-scripts or afterthoughts could even be crammed sideways or upside-down into any remaining space. One could also be momentarily surprised by her creative, though very specific, use of compound nouns such as Herumwirtschaften (presumably meaning, in a pejorative sense, “going from one business deal to the next”, or “doing business all over the place”). Puzzling endlessly over these enigmatic scrawls in an otherwise handsome calligraphic landscape was like looking for missing pieces in the clear blue sky of an enormous jigsaw; but more often than not, as though through some optical illusion the connecting loops suddenly rearranged themselves into a meaningful word, and the sentence fell into place.

Aside from legibility, there were other complicating factors. Alma was trilingual, so depending on the recipient – or even the country she happened to be in at the time – she wrote in English, German and French, and with varying degrees of formality according to whether she was addressing a professional colleague, personal acquaintance or a very close friend. While her early letters in English provided initial clues to the idiosyncrasies of her style and revealed her forthright and enthusiastic tone of voice, it soon became apparent that she did not hesitate to use several languages in the one letter. When writing to her Swiss friend Werner Reinhart, himself also trilingual, she frequently changed arbitrarily from one language to the other, many times in mid-sentence, as though thinking in all three languages at once. ←xxiii | xxiv→Often it seems she just used the most apt of the colloquial expressions that sprang to mind, or perhaps she switched to a more familiar tongue when hurrying, although it might simply have related to the spontaneous way in which she processed her thoughts. Whatever the reason, especially in her letters to Reinhart the playful mix of English, German and French is an essential part of their intimate character, so in order to preserve and represent that mix we have chosen to keep the shorter phrases and individual words as written, providing an English equivalent in square brackets. Where the new language involves a longer passage, we have indicated the change but continued the text in English. In later years language mixing happens less often, partly because her personal circumstances changed with her marriage, and almost certainly because the social and political environment increasingly required a more cautious approach.

While German was still very much her third language, Alma struggled with the difficult word order and tended to use a more typically English sentence construction, one that sometimes made long sentences easier for an English-speaking reader to comprehend. Occasionally, however, when she was writing in English but clearly thinking in German, her language became almost comically entangled where she used German sentence construction, or translated German words and idioms too literally. In addition, she never really concerned herself with grammatical punctuation, a vital component of German syntax. Commas are strangely absent even from some of her letters in English. Capitals are used in an arbitrary fashion, new paragraphs start either at random or not at all, and ampersands (in English) or the abbreviation “u.” for und (in German) are habitual, so wherever possible these features have been reproduced in the text.

Details

- Pages

- XXVIII, 642

- Year

- 2021

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800790223

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800790230

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800790247

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781800790216

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18266

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (September)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XXVIII, 642 pp., 32 fig. b/w.