History of the Swiss Watch Industry

From Jacques David to Nicolas Hayek- Third edition

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Author

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The Swiss Watch Industry during the first part of the 19th century (1800–1870)

- 1.1 The triumph of établissage

- An example of an établisseur: the DuBois family of Le Locle

- Why was établissage successful?

- 1.2 The technical evolution of products

- An innovation directed to the quality of products

- The hard beginnings of mechanization

- 1.3 The outlets of the Swiss watch industry: the global market

- 1.4 Rival nations

- Notes

- Chapter 2: The challenge of industrialization (1870–1918)

- 2.1 The shock of Philadelphia: the American competitors

- 2.2 The structural modernization of Swiss watchmaking

- The emergence of the factory

- Birth of the machine tools industry

- The modernization of watchmaking schools

- Banks and the modernization of watchmaking

- The organization of trade unions

- A limited industrial concentration

- 2.3 Selling: evolution of products and markets

- The beginning of mass communication

- 2.4 Towards organized capitalism

- The blooming of employers’ associations

- The Société Intercantonale des Industries du Jura – Chambre Suisse de l’Horlogerie

- The temptation of cartels

- 2.5 The Swiss watch industry during World War I

- The production of munitions

- The closure of the Russian market

- Notes

- Chapter 3: The watchmaking cartel (1920–1960)

- 3.1 The problem of chablonnage and the struggle against industrial transplantation

- The United States

- Japan

- 3.2 The maintenance of an industrial district structure

- 3.3 The setting up of the cartel

- The adoption of watchmaking agreements (1928)

- Setting up a trust: the creation of the ASUAG (1931)

- The legal intervention of the State (1934)

- The labor peace agreement

- 3.4 The consequences of the cartel

- The maintenance of the structures

- The creation of the Société suisse pour l’industrie horlogère SA (SSIH)

- The failure of the struggle against chablonnage and the emergence of new watchmaking nations

- 3.5 New products, new markets

- Notes

- Chapter 4: Liberalization and globalization (1960–2010)

- 4.1 Decartelization

- Maintaining control over Swiss production

- 4.2 The quartz revolution

- 4.3 The origins of the “watchmaking crisis”

- 4.4 Industrial concentration and the appearance of watch groups

- The first wave of mergers

- The birth of the Swatch Group

- The main watch groups in the 2000s

- An independent firm: Rolex

- The exception of Geneva: the evolution of luxury watch makers during the second part of the 20th century

- 4.5 The globalization of ownership and manufacturing

- Some subcontractors coping with globalization: the case makers

- 4.6 Towards luxury

- Notes

- Conclusion

- References

- 1. Archival Sources

- 2. Published Sources

- 3. Books and articles

For nearly two centuries, Swiss watches have exerted an insolent domination over the world market. Moreover, despite several crises, this supremacy has never been successfully challenged. The success story of the Swiss watch industry has been and still is largely explained as the result of a long tradition of manufacturing precision instruments, a widely shared technical culture, and an industrial organization as a flexible production system which enabled it to answer all the needs of customers. However, this traditional account, currently kept alive by the marketing strategies of watch companies and highlighting a kind of a timeless “Swiss genius”, has to be reconsidered in the light of economic history.

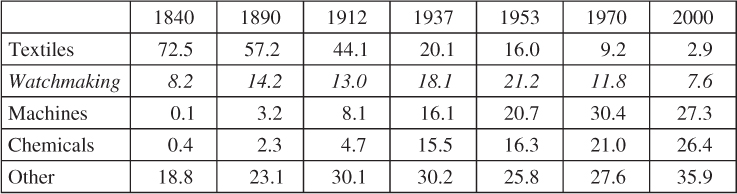

Watchmaking is certainly one of the oldest and most representative industries of Switzerland. A quick glance at the evolution of the foreign trade statistics of the country between 1840 and 2000 makes this importance evident (Table 1). During these two centuries of history, watchmaking is indeed one of the four main Swiss export industries. Together with textiles, machines and chemicals, it largely contributed to making Switzerland one of the richest countries of the world.

The structure of foreign trade shows that watchmaking is, after textiles, the second largest export industry of Switzerland between 1840 and 1937, and even the first in 1953. Moreover, its importance tends to strengthen during these years, with the percentage of exports growing from 8.2% to 21.1%. In the second part of the 20th century, watchmaking is third, below chemicals and machines, two sectors whose growth was particularly high after the war. As for its relative importance, it certainly appears to be decreasing, but this fall-off shows above all a general expansion of the Swiss economy, especially characterized by the dynamism of many sectors, as shown in Table 1 with the sharp increase of “other industries”.

The weight of watchmaking in the domestic economy, and the importance watchmaking companies have attached to their own history in their PR policy since the beginning of the 1990s, gave birth to many books and publications. Yet paradoxically, its general history is still unknown and not easily to access. Books are usually limited to a firm, a region or an individual, so that it is difficult to have an overview of the history of the Swiss watch industry in the long run. So, the aim of this book is to offer a general history ← 1 | 2 → of Swiss watchmaking since the middle of the 19th century. The approach adopted here is that of economic and social history. It focuses on the particular structure of this business (industrial districts, Statut horloger and groups of firms), as well as on the technical evolution of products (pocket watches, wristwatches and quartz watches), export outlets, rival industries (British, American, then Japanese), the intervention of public authorities (cartels and liberalization) and the relationships with workers’ unions.

Table 1:Relative importance of watchmaking in Swiss foreign trade, 1840-2000 (value as a %)

Source:Veyrassat, Béatrice, “Commerce extérieur”, Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse, <www.dhs.ch> (site accessed 21 June 2009) and official Swiss foreign trade statistics, <www.bfs.admin.ch> (site accessed 21 June 2009).

During the years 1800–2000, the Swiss watch industry faced two main challenges, two revolutions which threatened its existence and led to two major reconversion crises.

The first challenge was industrialization. It occurred during the 1870s and 1880s when the American watchmakers, mainly the Waltham Watch Co. and the Elgin Watch Co., forced Swiss watchmakers to adapt their system of production, with the introduction of machines and the construction of modern factories. The issue was the production of watches: the Swiss had to learn to manufacture standardized products. It was definitely a challenge, which caused considerable ferment amongst Swiss watchmakers until the 1900s. Led by a few industrialists, among whom was Jacques David, technical director of the company Longines, the Swiss watchmakers succeeded in adapting their system of production and overcoming American competition. Around 1900, they controlled about 90% of the world market.

The second challenge was marketing. Seen from a technical point of view, it appears to be what is usually called the “quartz revolution” and led to what is commonly described in Switzerland as the “watch crisis” (crise horlogère). However, this challenge went beyond its technical dimension. A new adaptation of the structures of the Swiss watch industry became a necessity, not only due to the launch of quartz watches on world market in ← 2 | 3 → the 1970s, but also because powerful industrial groups emerged as competitors, such as Seiko in Japan and Timex in the United States. The issue was not being able to produce watches but being able to sell them. Thus, the 1970s and 1980s are characterized by a restructuring of the Swiss watch industry, to follow the new rules of marketing. New business leaders, among whom was Nicolas G. Hayek, took charge of industrial groups in which they rationalized production and reinvented commercial policy. This marketing revolution enabled Switzerland to strengthen its dominant position on the world market at the beginning of the 21st century.

If one is to really personify the Swiss watch industry between 1800 and 2000, it would be necessary to add a third person: Sydney de Coulon, general director then delegate of the Board of Directors (administrateur-délégué) of Ébauches SA from 1932 to 1964. He is the man who personifies the cartel and the Statut horloger. He embodies the Swiss watch industry which successfully took on the American challenge of industrialization and then organized itself within rigid structures in order to protect its comparative advantage on the world market. In this context of a real bureaucratization of watchmaking, the domination of Swiss watchmakers on the world market continued until the emergence of competitors in the United States and Japan during the 1960s.

This book is the result of many years spent studying watch history, an activity which led me to consult many archives and to collaborate with numerous persons. It is unfortunately not possible to personally thank all who welcomed me in their institutions, allowed me to interview them and contributed to my work. However, I would like to give special thanks to the whole staff of the Musée international d’horlogerie, at La Chaux-de-Fonds (Switzerland), particularly to Jean-Michel Piguet and Laurence Bodenmann, Patrick Rérat from the University of Neuchâtel, and Patrick Linder, director of the Jura Bernois Chamber of Commerce, for their kind help and availability. Without them, it would not have been possible to finish this book. Also, I sincerely thank Alain Cortat for his remarks, comments and suggestions made on previous versions of the manuscript. Finally, I want to thank Richard Watkins for his kind help translating this book and making it available to a worldwide audience.

This third edition is an updated and slightly corrected version of previous editions. I thank all the readers for their very helpful comments and constructive critics.

Kyoto, October 2014

← 3 | 4 →

Map 1:Switzerland and the Watch Industrial District

Source:Designed by Patrick Rérat, University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland

← 4 | 5 →

The Swiss Watch Industry during the first part of the 19th century (1800–1870)

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 164

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034316453

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035108071

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035193824

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035193831

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0351-0807-1

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2011 (November)

- Keywords

- Economic History History of Science and Technology innovation industrial policy industrialization globalization Switzerland - Contemporary History delocalization

- Published

- Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2011. VIII, 164 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG