Inspired by BBC Radio’s “Desert Island Discs,” the Peter Lang Group presents ‘Peak Reads & Playlists’.

Join us on a journey to the mountain peaks near our Lausanne headquarters where we speak with our esteemed series editors.

In this interview format, our guests share the books, music, and food that would keep them company if they were whisked away alone to this beautiful mountain setting. They’ll explore the reasons behind their choices, revealing the influence each has had on their lives. Get a glimpse into the hearts and minds of the Peter Lang community.

Name: Dr. Irene Maria F. Blayer

Job Title: Full Professor

Series: Interdisciplinary Studies in Diasporas

Books

> Tell us, which fiction and/or non-fiction books would take spots on your list? Which FICTION title would take the coveted first spot on your list?

I will weave the question through three books that have quietly, yet decisively, left an indelible mark: the inner weather of a solitary self in Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet; the drift and disorientation of an uprooted circle in Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises; and the urban chorus that hums through Cela’s The Hive. Together, they open conversations about belonging, language, everyday labour, and the inventive forms literature forges to hold a fractured modern society. These readings bind inner life to the social fabric and treat form as an ethical choice, aligning with my ongoing preoccupation with home and diasporic belonging.

Fernando Pessoa, Livro do Desassossego (The Book of Disquiet), a masterclass in voice and self-division that sharpens attention to tone, aphorism, and the porous border between author and persona, asking what ‘home’ means when identity is multiple. Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises., a landmark portrait of the “Lost Generation,” where communal drift, ritual and claims of authenticity collide with modern decadence, unrequited love, desire, exile and aimlessness; a counterpoint to Pessoa’s inward gaze. Camilo José Cela, La colmena (The Hive), a mosaic of micro-scenes that builds a collective self-portrait; contingency―who meets whom, where, and when― powers meaning, and fragmentation mirrors a society frayed yet interdependent.

Music

> The mountain ranges have spectacular acoustics. Which 5 MUSICAL RECORDINGS would you take to enjoy whilst up on the summit and why?

It is never easy to confine a lifetime of listening to a few tracks, but given the space and the opportunity, I would let Pressler’s Chopin Nocturne and Pires’s Clair de lune hush the dawn, then open the day with Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and Grieg’s Peer Gynt in bright, wind-swept colour. As shadows lengthen, Miles Davis’s Blue in Green invites quiet reflection, before Aznavour’s La bohème warms the twilight with memory and longing. Finally, Louis Armstrong’s What a Wonderful World sends us down the mountain with a simple, grateful blessing.

Food

> We couldn’t let our community feed their souls but not their bodies, so which FOOD DISH would you choose to take with you on the mountain retreat?

Some chocolate would suffice, my enduring favourite, inviting slow savouring; nothing that competes, only complements.

Thank you to Dr Irene Maria F. Blayer for joining us up the mountain!

Discover the series here – Interdisciplinary Studies in Diasporas

Inspired by BBC Radio’s “Desert Island Discs,” the Peter Lang Group presents ‘Peak Reads & Playlists’.

Join us on a journey to the mountain peaks near our Lausanne headquarters where we speak with our esteemed series editors.

In this interview format, our guests share the books, music, and food that would keep them company if they were whisked away alone to this beautiful mountain setting. They’ll explore the reasons behind their choices, revealing the influence each has had on their lives. Get a glimpse into the hearts and minds of the Peter Lang community.

Name: Dr Valentina Bold

Job Title: Series Editor

Series: Studies in the History and Culture of Scotland

Books

> Which FICTION title would take the coveted first spot on your list?

James Hogg, The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824) is the one fiction title that surprises me on each reading. It is original and startlingly innovative: as relevant today as it was when it was written. The narrators are unreliable and might be insane; characters might not exist (hardly any are likeable); religious values are distorted and destructive. Justified Sinner is set in a world where the natural and supernatural are a shifting continuum, where present and past co-exist. No one can be trusted, least of all the author.

> If you were offered the chance to take a NON-FICTION title, which would you choose?

Jen Stout’s Night Train to Odesa (2024) gripped me from the first page to the last. It is a personal, direct and heartfelt account of conflict and its impact, particularly on women. Through a journalist’s clear vision, this is perceptive, insightful, compassionate writing, from a Shetlander’s perspective, focussed on Ukraine.

> We’re feeling generous so we’ll allow you one more book, your choice of FICTION or NON-FICTION – which one makes the list?

This one has to be poetry: to feed the soul as well as the mind. I would like the ‘O Choille gu Bearradh / From Wood to Ridge’, the Collected Poems of Somhairle MacGill-Eain / Sorley MacLean (1911 – 1996) edited by Christopher Whyte. There is a wealth of experience here that goes beyond the personal, into the political, natural and imaginative, from the Gàidhealtachd into Europe, with consummate ease, anchored in tradition, exploring with imagination and grace.

Music

> The mountain ranges have spectacular acoustics. Which 5 MUSICAL RECORDINGS would you take to enjoy whilst up on the summit and why?

- The McCalmans, ‘The Ettrick Shepherd’

Beautiful settings of James Hogg’s poetry and songs: varied, haunting and entertaining.

2. Sheena Wellington, ‘Hamely Fare’

Great selection of Scottish tradition from one of our finest, and most influential, singers: powerful, important and compassionate.

3. Karine Polwart, ‘This is Karine Polwart’

Fifty songs from a wonderful singer, which would help me remember Scotland in all its diverse moods.

4. Emily Smith, ‘This is Emily Smith’

All three women singers in my list are song-writers as well as outstanding performers; this selection is remarkable for its stylistic range as well as Smith’s superb delivery.

5. Nicola Benedetti, ‘This is Nicola Benedetti’

For when I need instrumental space to contemplate, and to celebrate, there would be nothing better than violinist extraordinaire, in this wide-ranging collection.

Food

> We couldn’t let our community feed their souls but not their bodies, so which FOOD DISH would you choose to take with you on the mountain retreat?

Sweet soul food by choice: shortbread, following a traditional recipe such as these.

Thank you to Dr Valentina Bold for joining us up the mountain!

Discover the series here – Studies in the History and Culture of Scotland

One of the most profound moments for an academic publisher is when we lose one of our authors. Their work is a lasting legacy, a reminder of the career and passion they dedicated their lives to. For us, as their publishers, we become the caretakers of that legacy.

This responsibility becomes even more significant when a project is still in production. Fortunately, we often have the honour of working with the author’s family or co-authors to ensure their work continues to reach the global research community.

This is the case with a forthcoming trio of titles: Hope and Despair, Wounded Nostalgia, and The Madness That Is Also in Us—English translations of works by the renowned psychiatrist Eugenio Borgna.

Eugenio Borgna, who passed away the 4th of December 2024, aged 94, was the most prominent Italian psychiatrist of his time. His works have made mental illness comprehensible to the readership and removed the boundaries created by misconception and fear. In his writing he makes acceptable what the society instinctively rejected as different and dangerous. His written work is a complement to Franco Basaglia’s psychiatric revolution.

We are proud to be able to publish these translated texts and continue to raise awareness of Eugenio Borgna’s work and the difference he made in making mental illness better understood.

Each title will feature a preface and we share a small snippet of these here.

“I write as an editor for the publishing house that is bringing Borgna into English for the first time, with a trilogy composed of Hope and Despair, Wounded Nostalgia, and The Madness That Is Also in Us. Again here, one need only glance at the titles to grasp the author’s aims: as a phenomenologist, opposed to any form of biological reductionism of psychiatric disorders and backed by direct clinical experience, the intention is to make madness understandable, acceptable, “normalize” it, in today’s parlance, by demonstrating readers its proximity to us all.”

Ilaria de Seta

“Of Eugenio Borgna, we appreciate his objectivity and composure, the measure that gives his texts, never caustic or brutal, the hushed tone of quiet reflection. Yet this moderation conceals a great radicalism. If there is such a thing as an intimately relational psychiatry, based on listening, “humanistic” and anti-authoritarian, this is precisely the psychiatry to associate with Borgna”.

Michele Dantini

“Eugenio Borgna is, equally with Franco Basaglia, the most important Italian psychiatrist. If Basaglia gave psychiatric patients back their freedom (with his reform that led to the passage of Law 180 in Italy in 1978), Borgna gave psychiatry back its soul.”

Stefano Redaelli

Disclaimer: The views and opinions below are the authors own, based on their own academic research and study, and are not representative of the Peter Lang Group

When we began compiling Confronting Toxic Rhetoric in early 2023, we imagined it as a way to support writing teachers who were teaching argument, evidence, and rhetorical ethos in a time when many were still reeling from four years of Trump-era post-truth and fake news. Perhaps naively, we did not consider that the book would hit the shelves the very month that Trump would be re-elected back into the oval office, and that we would be marketing it as we witness, arguably, some of the most inflammatory rhetoric and behavior our country has ever known: Elon Musk performing the nazi salute on television, Trump’s executive orders against trans and non-binary people (referring to “transgender insanity,” nbc news), immigrants being taken from their homes by ICE (referring to murderers, rapists, burglars, and criminals, abc news), and measures toward diversity, equity, and inclusion eliminated. The ways that people are being hurt by his words and actions are practically endless. The toxic rhetoric used by the new presidential administration seems to have only one purpose: to incite chaos, anger, fear, division, and violence not only in America, but abroad, as Trump attempts to make claims on land and instigate feuds in Canada, Greenland, Ukraine, Mexico, the Middle East, and elsewhere.

This continual onslaught of “toxic rhetoric,” described by John Duffy as “a discourse of denial—denial of science, of diversity, of democracy, of change, of the commitment to equality and individual freedom” (p. xii), is what makes Confronting Toxic Rhetoric timelier than we even realized as we began assembling the book only two years ago. Toxic rhetoric is gaining strength and permission not only to exist, but also to be spread widely and even exalted. Is toxic rhetoric accepted as a norm? Back, say, in 2017, we were horrified and shocked by the permissiveness granted to the vocal and visual instigators of the Charlottesville Unite the Right riot. Was our nation perhaps less shocked when a shooter entered a synagogue a year later and murdered 11 innocent people praying there? Had we already completely embraced toxic rhetoric in 2022 when 10 Black men and women were shot to death in a Buffalo grocery store?

These incidents all have one thing in common: they were incited or supported by toxic rhetoric used specifically by Donald Trump. In the case of Charlottesville, it was written many times in many places that “President Trump … gave the white supremacists cover to come out of the shadows” (Time, see also ABC News, AP for more examples). The shooter of the victims at Tree of Life Synagogue was an active member of Gab, a social media site where “users could freely traffic in the basest kinds of hate speech” and find a “a rebranding of traditional white nationalism by a new generation of believers that emerged online around 2014 and came to prominence by attaching itself to Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign” (SPLC). The Buffalo grocery store attacker had written a manifesto outlining his belief in the Great Replacement Theory, which “asserts that there is a plan to bring nonwhite people to Western countries to replace whites” (Economist). Trump used this same toxic rhetoric of replacement theory when claiming that migrants were brought into the U.S. to vote for Biden in the 2020 election, thus illegally handing Biden the presidency (NPR).

All of these attacks, and many more like them, were motivated by racism, antisemitism, and white supremacy; we are seeing and hearing the toxic rhetoric of the great replacement theory and white nationalist conspiracy theories everywhere. And so are our students. On college campuses across the U.S., we see students engaging in protest, oftentimes themselves using toxic rhetoric even if they don’t always understand the meaning behind what they’re saying (see, for example, a survey of UC Berkeley students, which showed that 46% of student protestors who chanted “From the River to the Sea” did not know the names or locations of neither “the river” nor “the sea,” nor what lies between, Newsweek). But on many campuses, students are silent: silent about the presidential election, about recent executive orders that might even harm them or their families, about atrocities across the world.

What can we, educators, do about this constant exposure to toxic words and behaviors? Many people are taking news or social media “fasts,” that is, trying to avoid that which might harm them. Or they’re focusing their energies on activism: making calls to government officials and volunteering to support those whose rights are being challenged. But we don’t always know what our students are doing, or how they’re reacting to, or worse, absorbing and then replicating the toxic rhetoric onslaught. As Jamie says so eloquently in Chapter 1 of Confronting Toxic Rhetoric, as teachers, we can help students “to entertain multiple sides of arguments, discuss difficult topics, and disagree with each other respectfully […to] help solve some of our nation’s complex problems. Over time and with iteration, our work could engender a groundswell that could lead to meaningful and lasting change in American discourse, politics, and culture” (pg). Teaching students to engage in respectful discourse is no longer something we can do; it is something we must do.

Thus, we highlight two strategies from our collection for use in writing classrooms to support and encourage students as they navigate, disrupt, and confront toxic rhetoric. We learned these from teacher contributors to Confronting Toxic Rhetoric, where you can read more deeply about these strategies and several others.

One: Intervention through Public Memory

Whitney Jordan Adams teaches at Berry College, two hours from Atlanta, GA, and only a few miles from Stone Mountain, a current day campground that is also “the site of a Confederate memorial to Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis. It is the site of the establishment of the Ku Klux Klan’s (KKK) Second Empire in 1915” (p. 24). For Berry, teaching students to examine the toxic rhetoric around Stone Mountain is an imperative that “provides college students a framework to consider how public memory, and specifically monuments, can be exclusionary or inclusionary” (p. 24). Students in Adams’ class learn about “heritage,” “tourism reset,” and how one “rendition” of public memory “might take precedence and wipe out others (p. 33). Students read public documents and learn about how larger national stories are crafted as related to monuments such as Stone Mountain. Many students in Adams’ class come to see Stone Mountain from a new angle, which can be challenging for those students who knew it as “an innocuous place for hiking and family fun” (p. 33) or those whose family values have taught them to align with confederate world views (p. 32). Adams cites Wheatley, who would refer to this challenge as a “positive disturbance” (p. 34), and she explains that this is the purpose of the course – for students’ views to be ruptured so that nuance can be allowed in. At the end of her chapter, Adams asks educators to “continue to provide opportunities for students to consider the historical sites around them and explore the situated and complex nature and histories of those sites, their origin stories, whom they include and exclude, and how those who take advantage of their beauty and location participate or resist in cultural oppression, structural perversion, or white supremacy” (p. 34). Because these sites are everywhere, and because they are challenged and contested on a national stage and in classrooms (see, for instance, Utah public schools, where nazi and confederate flags are allowed to be displayed “in accordance with curriculum,” Salt Lake Tribune), students are learning a valuable skill in Adams’ class that they can take with them anywhere: how to participate in conversations about history and its often toxic artifacts.

Two: Unveiling Media Motivation

When Sarah Lonelodge was a PhD student at Oklahoma State University in spring of 2020, she had the opportunity to develop an advanced composition course “focused on politically charged communication” that helped students “participate meaningfully and thoughtfully in public discourses in ways that might resist and counteract the damage done by toxic rhetoric” (p. 102). Early that spring, several events occurred right on top of each other – the Australian brush fires, the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the death of Kobe Bryant and his young daughter, and the Trump impeachment trial and subsequent acquittal. As Lonelodge describes it, “my students and I could feel a shift – there was a dread hovering over us. I could see it as they scrolled through their phones before class began” (p. 103). The moment could not have been more kairotic for a course on public discourse, but Lonelodge wanted her course to be more than writing about social change. She wanted her students to engage as citizens (p. 104). For example, as the Covid-19 pandemic unfolded (before it was officially a pandemic), students learned about propaganda and how it works. They created multimodal projects – podcasts, presentations, narrated slides – where they learned to provide evidence to demonstrate types of propaganda and persuasion related to topics of their choosing. Lonelodge explains, “the multimodal nature of the project offered a significant amount of creativity and creative thinking from students as they explored the use of screenshots, embedded video, and other composing options,” (p. 109). Learning to compose multimodally is surely a productive outcome, yet we believe the most useful strategy Lonelodge employed in helping students counter toxic rhetoric was teaching them to analyze current events as found on the daily in the media and to understand how that media works to persuade, sometimes in toxic ways; the students developed and used a heuristic for determining if a text was persuasion or propaganda. Now they are now practiced in “identifying, analyzing, and responding to demagoguery, propaganda, and misinformation through various media,” (pg. 108) and as Lonelodge says, they have learned to respond “in real time.”

Finally,in the conclusion to Confronting Toxic Rhetoric, Rachel Ketai writes a letter to John Duffy in which she says, “I came to the field of rhetoric and composition to promote equity and access in education. I should have expected that this path would confront me with disagreements and controversy. Change in any direction requires conflict, and in 2023, that can look like an unfollow on social media or a piñata beating on campus” (p 218). In terms of disagreements and controversy, things have not gotten much better in 2025; in fact, they may be worse. But Ketai pushes forward, and we hope you will, too. She continues, “What my students and I need is not to avoid or scrub out the lines of difference that separate us from those we disagree with. We need to practice reading and writing and listening and speaking across those lines of difference in ways that will build better conversations and communities” (page 218). We hope you also find those practices that help you and your students toward better conversations and communities among the pages of Confronting Toxic Rhetoric.

Find the book here: https://www.peterlang.com/document/1446367

Having fun is a serious business. IndigePop: A Companion, an edited collection published in December 2024 by Peter Lang, makes this point as it explores the dynamic and multifaceted field of contemporary Indigenous popular culture. Indigenous popular culture celebrates the Indigenous popular and Indigenous nerdy creativity in all their manifestations, gaining increasing momentum since the turn of the twenty-first century. The contributions in the book offer a range of perspectives on the Indigenous popular by scholars, artists and practitioners who work with and in the field of Indigenous popular culture in various capacities, from different standpoints, and in a range of geopolitical contexts. The origins of the book go back to the Indigenous Comic Con 2, which took place in Albuquerque, New Mexico, in November 2017, and which we had the privilege of attending. There we had a chance to speak to participants and organizers, who generously shared their perspectives on the event and on Indigenous popular culture with us. These conversations and experiences inform the book in many significant ways.

Popular culture moves fast. As we were working on the book, Indigenous popular culture continued its dynamic expansion, going from strength to strength. Dr. Lee Francis 4 (Pueblo of Laguna), the founder of the Indigenous Comic Con and the Executive Director of Native Realities who contributed to IndigePop in more ways than one, is at the center of many of the initiatives in the field, both old and new. We had a chance to interview him at the Indigenous Comic Con back in 2017, and we were delighted and honored when he agreed to speak to us about the state of the art of Indigenous popular culture on the threshold of 2025. His remarks give insights into the latest developments and milestones of Indigenous popular culture, and also situate the book in its larger context.

Interview with Dr. Lee Francis 4

12 December 2024, Zoom

*The interview is slightly edited for clarity and readability.

SVETLANA

During our interview back then [in 2017] we asked you about the development of Indigenous pop culture at the time, and where it was at the time. Seven years have passed now – almost exactly, it was November – so, which significant trends and developments have taken place since, in your view? What is the current status of Indigenous pop culture?

LEE

Yeah. When we got started… And I mean, we gotta go back a little bit too, because when I first started working with comics that was 2012, and there was this sort of emerging… There were some folks that were working on things, but really not a lot – there was this small group, the Indigenous Narratives Collective, there was Arigon Starr’s work and John Proudstar and the initial folks that we were working with. And really all the way for that first four years, up until about 2016 when we launched the first Comic Con, there wasn’t… you know, there were people that were really sort of scattered, doing small things. And I think what that first event did was really put a lot of names into the public sphere. And so, what we’ve seen in these last seven years, from 2017 on, is really this explosion of Indigenous pop culture creativity. So you see a lot of folks that have been a part of the comic cons – the IPX and Indigenous Comic Con moving forward – you’ve seen a lot of them just taking off on the work that they have, the collaborations that they’ve contributed to, a lot of the folks that were a part of those initial comic book works that we did, we’re seeing a lot of their work now into the mainstream. You know, just in that time period we’ve seen the rise of a lot more Native television, a lot more Native cinema – so, Prey came out on Hulu; you saw Reservation Dogs, of course, and the work that they did with that; you see the Marvel stuff, you see Echo and you see Kahhori from the What If…? series getting her own comic now. So, you’re seeing a lot of these developments that weren’t really present seven years ago, so I think, really, the biggest impact that we had was putting all of that work front and center and really allowing people to find those people online. I still get folks, but definitely within those three initial years people were contacting us, being like, “Who are your guests? Who are your vendors? We wanna find more artists,” with people coming out to interview and put together projects based on the people that we were working with and collaborating with. So, I think that’s really what we’ve seen, is just this explosion of talent. And now you have all these kids’ books that are out, and you still have more mass media that’s come out – they did the Marvel Indigenous Voices [in 2020], and they’re still releasing pieces of that, those are all people that were really a part of the first inception of this, first couple of years.

SVETLANA

And when you look at all these developments, are there any milestones that you think were particularly influential?

LEE

Yeah, the release of Reservation Dogs – that was, like, three years ago, four years ago – I think that was hugely influential. I think the Marvel Indigenous Voices was hugely influential. So, I think those two were really putting folks into these mainstream conversations and pop culture conversations. I mean, Sterlin Harjo won the McArthur Fellowship within this last year. So, that is what we’re seeing. And then you see the cartoons and the kids’ stuff that’s come out, and Spirit Rangers was another milestone, so you have a kids’ cartoon on Netflix. So I think those are these big moments, but I even think just… obviously, continuing on with the Comic Con, with Pop Culture X, the stuff that we’ve done, now we’re seeing more of those – so, SkasdiCon in Oklahoma, Cherokee Nation; the áyA Con in Denver; these other Native-centered, Native-specific conventions where people are, like, yeah, we still want people to come together, we still wanna have these moments where we can do this kind of work and these collaborative, amazing creative spaces. I think those are still a lot of the great milestones that we’ve had.

SVETLANA

Yeah. I guess the first Comic Con remains this watershed moment for Indigenous pop culture, right?

LEE

Yeah. Yeah. I think 2016 really set a lot of things in motion. And looking back on it, in building careers, connecting up with folks, I think that really… it was so unique, it’s something that I feel was so needed, and continues to be needed, that I was just… I’m always stoked to have founded it and been influential in continuing its success.

SVETLANA

So, it did impact – and change, you could say, also – Indigenous pop culture, right?

LEE

I absolutely believe it did, yeah. I mean, you’ll have to check in with other folks, but for me I think there is a definite change from this moment.

KATI

You talked about this a little bit already, but if you look at the bigger picture, so how do you think, or do you think that the Indigenous Comic Con has had an impact or influence on the popular culture at large?

LEE

I think it gave Native folks, Indigenous folks a space to be able to showcase their talent, and in a different way that wasn’t tied to previous notions of what is Indigenous art. And I still think that that’s the impact. The impact is allowing Native creatives permission, you know – because they know there is a space where they’re gonna be welcomed for doing things that are avant-garde, for doing things that are not conforming to what the Americanized ideal of… the American mythology of Native art, Native identity is supposed to look like. So, you still have cosplay, you still have comic books, you still have these reappropriations of mainstream – or Indiginizations of mainstream pop culture things that Native folks are still grabbing onto and claiming as their own. So, I think it’s still really about the creatives, and I think that that’s the part that has been the longest lasting impact.

KATI

If you think, then, a little bit the other way around, do you think Indigenous representation in mainstream popular culture is improving?

LEE

I think… yeah, slowly, very slowly. You know, when I talk about this, I’m, like, this is four hundred years of Natives in pop culture, and I continue to write about this, this liminal space that Native folks occupy – you still see it. I mean, every year we have to put out, you know, please don’t dress up for Halloween, Natives are not a costume. So, there’s not been this overnight shift, but you’re seeing a lot more in the conversation of folks that are wanting to be much more authentic, much more deliberate in their ways that they’re framing – especially artistically – the ways that they’re writing about or framing Native identity and Native folks and being much more specific about it. There’s still a long way to go, you still see a lot of the same tropes that show up, and it is one of the dilemmas… in any type of identity markers, the dilemma is how do you showcase that in a visual way, so the people understand that that person comes from this particular heritage. With Native folks, because it’s so specific, there are so many cultural tropes, stereotypes, but also touchpoints, because of the interchange of ideas, because of the interchange of art throughout histories and time immemorial, that’s the balance that still continues on, especially as a Native artist. So, how do we recognize that a character or somebody we put out there is Native without certain markings, without certain pieces to that? So, there’s still a balance in that [that] I think is always gonna be a struggle, because our identity has been dictated to us for four hundred years, and we’ve just… I mean, it’s been within two generations, three generations that we’ve been reclaiming it – in mass media, in popular media.

KATI

Yeah, yeah. The Indigenous Comic Con took place in North America, and many of the developments that we’ve been talking about had been taking place in North America as well. So, if you think in more global terms, how do you see Indigenous popular culture globally, developing on a more global scale?

LEE

There’s so much great work that’s going [on]… So, it exists sort of in two frames. I think you definitely see the idea of the Native American as a global concept, and so that’s still something that we’re trying to change those perceptions, because… I think that because it was American pop culture spreading everywhere you still have these entrenched views of what Native America is. For global Indigeneity, I think you’re still looking at an evolving terminology around how we’re codifying what does that mean. So, in some of my travels – obviously, we hosted a Comic Con in 2019 in Australia, and so talking about that, seeing what folks have been doing down there, and my colleague that was the host for that event [Cienan Muir] continues talking about Indigenous Australian identity and what does that mean for their popular culture. Because they have a different set of movies and films, and identity, but you can see things – I think one of the movies down there that was really solid… or it was a TV show, called Cleverman, and that was going on in 2017, I believe, and that was an Indigenous person with superpowers, and what they were doing with that. Now, that didn’t make it this direction, but it was something that was internal. You see the same thing with our Māori relations in New Zealand, they’re making comics and they’re putting things forward. So, I think a lot of this is using this medium, this pop culture spheres to be able to address the ways in which representation has been detrimental to Indigenous communities. And I think that that’s what we’re seeing globally – a lot of it having to do with digital access, and the ease with which you can put a lot of this forward.

KATI

We’ve been talking about the recent developments in the past years now, but there are certainly many exciting developments in Indigenous popular culture ahead. So, what is the vision going forward? Are there any specific new initiatives you would like to mention?

LEE

Yeah. This next year we’re going to be here on the East Coast, so we’ll be out here in North Carolina, so focusing some attention out here to our East Coast relatives, because, again, this concept of Indigenous identity is very Western-oriented. And so, wanting to continue the conversation and allow for Native creatives that are Eastern relations to be able to showcase their work as well, and inspire them to be a part of some of that stuff. So that’s one of the big things that I’ve been working on the last couple of years, really trying to get a lot of this work grounded on the East Coast and being able to tell more of these Eastern stories. I think that we’re doing a lot around world building. The new organization that we’ve brought everything under these last years is called the Indigenous Imagination Workshop, so the idea is how we’re cultivating a lot of these concepts coming from these places of fantasy and science fiction and Indigenous futurisms, how are we now applying that in our own communities. Like, what do we want for these fantastical worlds? If we have these superpowers, what do we do with them? How do we make our communities better? And then, how do we actualize that, that’s the inspiration to spark the imagination. So, I’m working on a piece right now that talks about this intersection of generational trauma, and intergenerational trauma, and its effects on the imagination. And so, what does that look like when you have… or doom and imagination, right? We can see all the terrible things, but we have continued to survive, and thrive in many ways, and so how does that look when you’re having to deal with trauma, ‘cause trauma creates roadblocks for imagining. So, how do we work through those and utilize pop culture and utilize these spaces to spark that imagination in our next generations?

SVETLANA

And one last question maybe. I was thinking about the importance – and we stressed it in the book as well – the importance of the celebratory aspect of Indigenous popular culture, the celebration and the having fun. So, I was wondering whether you have any thoughts on that.

LEE

I think it still comes down to celebration, right? Like, how do we have moments of joy? Even within the framing… I mean, everything is always political, but it’s this… I think the counterpoint in pop culture that still holds true, what we have available to us is to find ways to celebrate our identity, our continued exitance, without fetishizing tragedy. Because that’s been the perpetual narrative, it’s about fetishizing Native tragedy – everything [that] happened, look at the poor…, you know, look how terrible everything is for them. And so, the celebration, also, it’s celebration of resistance, celebration of empowerment. Celebration, I believe, gives you agency, and gives people the chance to… when you can celebrate, in moments, then you are able to more effectively dictate the terms through which you are going to navigate a colonial/postcolonial society.

SVETLANA

Yeah, very true. Thank you so very much, this was great! Thank you for your time, and for doing this.

Dr. Lee Francis 4, aka Dr. IndigiNerd, is the CEO of A Tribe Called Geek (ATCG) Media and the Executive Director of Native Realities, both of which are dedicated to creating pop culture media that celebrates Indigenous identity. He is the founder of the Indigenous Comic Con and an award-winning editor of over a dozen comic books and graphic novels. Lee has won accolades for his work on Ghost River, Sixkiller and Native New York. You can find more about his work on social media @dr_ indiginerd. He lives in North Carolina with his family.

Die Darstellung von Behinderung in der Literatur ist ein Spiegelbild gesellschaftlicher Haltungen, kultureller Diskurse und normativer Ordnungen. Literarische Werke von der Frühmoderne bis zur Gegenwart thematisieren Behinderung auf unterschiedliche Weise und reflektieren sowohl hegemoniale als auch marginalisierte Perspektiven. Die vorliegende Untersuchung mit dem Sammelband über Behinderung in der deutschsprachigen Literatur geht über die rein textliche Darstellung hinaus und beleuchtet, wie sich kulturelle Narrative rund um Behinderung über die Jahrhunderte hinweg gewandelt haben. Dabei stehen ästhetische und ideologische Aspekte im Mittelpunkt sowie auch Fragen der sozialen Verantwortung, der Partizipation und der Inklusion.

Die literarische Inszenierung von Behinderung

Literarische Figuren mit Behinderungen sind oft Projektionsflächen für gesellschaftliche Ängste, Hoffnungen und ethische Fragestellungen. In klassischen Werken wie den Erzählungen der Romantik oder den Dramen des Expressionismus dient Behinderung häufig als Symbol für eine innere oder gesellschaftliche Krise. So werden körperliche und geistige Einschränkungen in der Literatur vielfach metaphorisiert: Der blinde Seher in der Antike oder die deformierte Gestalt in der Romantik stehen beispielhaft für das Spannungsverhältnis zwischen Ästhetik, Wissen und Anderssein.

Im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert zeigt sich eine zunehmende Diversifizierung der Darstellungsweisen. Während im Nationalsozialismus Behinderung mit negativen Zuschreibungen verbunden wurde, kam es in der Nachkriegszeit zu einer schrittweisen Neubewertung. Die Literatur begann, sich mit den Erfahrungen von Menschen mit Behinderungen auseinanderzusetzen und legte den Fokus verstärkt auf deren Lebensrealitäten sowie gesellschaftliche Herausforderungen. Zugleich werden in der zeitgenössischen Literatur verstärkt diverse Behinderungsnarrative sichtbar, die sich nicht nur auf Defizit- oder Mitleidskonstruktionen stützen, sondern Agency, Selbstermächtigung und soziale Gerechtigkeit betonen.

Zwischen Stigmatisierung, Selbstermächtigung und sozialer Verantwortung

Ein zentrales Anliegen dieser Untersuchung ist es, die Ambivalenz in der literarischen Darstellung von Behinderung herauszuarbeiten. Während viele Werke tradierte Klischees und Stigmata reproduzieren, gibt es ebenso zahlreiche Texte, die sich der Thematik differenziert und kritisch nähern.

Ein besonders interessanter Wandel zeigt sich in der modernen Literatur und den Disability Studies: Behinderung wird nicht länger als individuelles Schicksal oder medizinisches Problem betrachtet, sondern als sozial konstruiertes Konzept hinterfragt. Romane und Autobiografien von Betroffenen gewinnen zunehmend an Bedeutung, da sie den Fokus auf Selbstermächtigung, Agency und intersektionale Diskriminierung legen. Die Repräsentation von Behinderung rückt in diesem Kontext nicht nur die persönlichen Herausforderungen in den Mittelpunkt, sondern ebenso strukturelle Exklusionsmechanismen, die in Gesellschaft und Kultur wirksam sind.

Soziale Verantwortung spielt dabei eine essenzielle Rolle: Literarische Darstellungen können entweder Inklusionsprozesse fördern oder bestehende Ausschlüsse weiter verfestigen. Die kritische Reflexion über diese Mechanismen ist ein zentraler Bestandteil zeitgenössischer literaturwissenschaftlicher Analysen und gesellschaftspolitischer Debatten.

Gesellschaftliche Relevanz und gegenwärtige Diskurse

Die literaturwissenschaftliche Reflexion über Behinderung trägt ferner dazu bei, gesellschaftliche Vorurteile aufzubrechen, Inklusion zu fördern und soziale Verantwortung in unterschiedlichen Bereichen zu stärken. Literatur kann ein wichtiges Instrument sein, um Normen zu hinterfragen und neue Perspektiven auf Diversität, Teilhabe und Gerechtigkeit zu eröffnen. Gleichzeitig zeigt sich, dass trotz der Fortschritte in der Repräsentation von Behinderung in der Literatur noch viel Aufklärungsarbeit notwendig ist. Insbesondere in Literatur und Film bestehen weiterhin stereotype Darstellungen, die Menschen mit Behinderungen auf ihre Defizite reduzieren. Der Band über die Behinderung in der deutschsprachigen Literatur möchte daher nicht nur eine wissenschaftliche Analyse bieten, sondern auch Impulse für eine breitere gesellschaftliche Diskussion setzen.

Ein weiteres zentrales Thema ist die Verbindung zwischen Literatur und politischen Bewegungen für Inklusion und Barrierefreiheit. Während einige literarische Werke aktiv zur Bewusstseinsbildung beitragen, perpetuieren andere diskriminierende Narrative. Die Verantwortung von Autor:innen, Kritiker:innen und Leser:innen wird in diesem Kontext zunehmend betont, da Literatur nicht isoliert von gesellschaftlichen Machtstrukturen existiert.

Fazit

Die Auseinandersetzung mit Behinderung in der Literatur ist also mehr als eine rein akademische Übung – sie ist ein Beitrag zur kritischen Reflexion gesellschaftlicher Normen, Werte und Machtstrukturen. Die literarische Repräsentation von Behinderung beeinflusst maßgeblich gesellschaftliche Diskurse über Inklusion, soziale Verantwortung und Gerechtigkeit.

Die Relevanz dieses Themas reicht weit über den literaturwissenschaftlichen Bereich hinaus und berührt interdisziplinäre Felder wie die Disability Studies, die Kulturwissenschaften und die Sozialwissenschaften. Der fortlaufende Dialog zwischen Literatur und Gesellschaft kann dazu beitragen, tradierte Vorstellungen von Normalität und Abweichung zu hinterfragen und inklusive Narrative zu stärken.

Behinderung ist kein Randthema, sondern ein zentraler Bestandteil menschlicher Erfahrung – und die Literatur kann helfen, diese Erfahrung in ihrer Vielschichtigkeit sichtbar zu machen und kritisch zu reflektieren. Es liegt in der Verantwortung aller Beteiligten, die bestehenden Narrative kontinuierlich zu hinterfragen und weiterzuentwickeln.

Das Buch „Behinderung in der deutschsprachigen Literatur”, herausgegeben von Habib Tekin und Leyla Coşan können Sie hier bestellen.

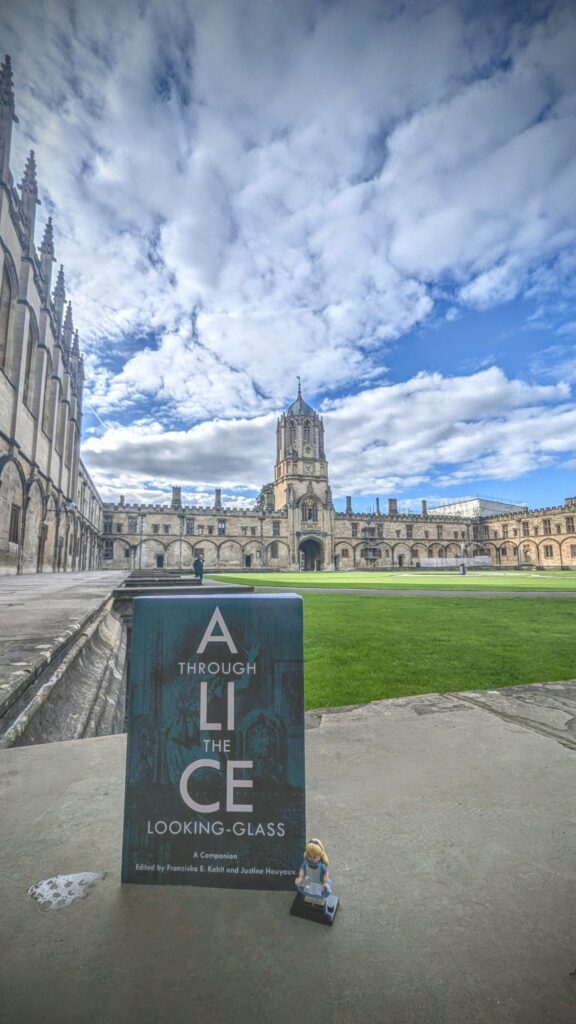

The 2024 book launches of ‘Alice Through the Looking-Glass: A Companion’ edited by Franziska E. Kohlt and Justine Houyaux were more than just book signings. They were immersive experiences that explored the mind of Lewis Carroll and the enduring legacy of his work. Held in two iconic locations—Oxford, the birthplace of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, and Los Angeles, the birthplace of Disney’s cinematic adaptations—these events demonstrated the power of a well-executed book launch, and how authors and editors can build on their research to craft an event. Here we explore what makes a successful book launch as part of an author marketing strategy.

Why Book Launches Matter

A successful book launch strategy can significantly boost a title’s visibility, generate buzz, and foster a dedicated readership. It’s an opportunity to connect with readers, colleagues, and fellow authors, to illustrate what the book can offer them and their own understanding of the topic.

The Magic Behind the Success

The book launches for ‘Alice Through the Looking-Glass’ were particularly successful due to a combination of factors:

1. A Unique Setting:

Oxford: By choosing Oxford, the editors tapped into the rich history and literary heritage of the city. As Franziska E. Kohlt explained, “The Oxford launch was a bit of a full, circle moment – I had worked with the archives kept at the library of Christ Church, where Lewis Carroll had lived and worked most his life, where he had met Alice, and written the Alice books, for such a long time.” This setting, so integral to the book itself inspired insightful discussions and tapped in to the historical context of Carroll’s work.

Los Angeles: This vibrant city provided a platform to better explore the cinematic adaptations of Alice and the evolving landscape of storytelling in the digital age.

“Both settings thus gave us access to unique discussions, with diverse audiences – to rethink pasts and futures of the interplay of arts, beliefs, society and technology – aspects whose intertwined nature we were keen to highlight in our book, and whose past and present echoes, we could reflect on (pun intended!), playfully – in a Carrollian spirit.” Kohlt

2. Engaging Programming:

Expert Panel Discussions: The launches featured expert panel discussions with scholars from various disciplines, offering diverse perspectives on Carroll’s work. As Kohlt noted, “At the Oxford launch we had the unique opportunity to hear from speakers from Victorian Literary Studies, History of Science, Theology, Business Studies and Theatre Studies, who could point to the items, and the places referenced in their articles.”

Interactive Exhibitions: By curating exhibitions of historical artifacts and related items the editors created immersive experiences that brought the book to life. The editors were inspired to convene an exhibition on the history of early cinematic technology, “beginning with early optical trickery to the history of its uses in magic and technology and how they shape our perception and understanding.”

Thematic Performances: Tying in magic lantern shows and other performances to the launch added a theatrical element reinforcing the book’s themes. A highlight was an Alice-themed Magic Lantern show commissioned especially for the launch. Related exhibitions encouraged attendees who may not have originally been aware of the book or the launch.

3. A Strong Author Presence:

Personal Insights: Kohlt shared personal anecdotes and insights into her research process, creating a deeper connection with the audience. She reflected on the complexities of Lewis Carroll and how his multifaceted nature shaped his writings. earing Hearing firsthand from an author or editor about how the book came to be can bring the book and its contents to life for a potential readership.

Engaging with Readers: By actively engaging with readers through book signings, Q&A sessions, and social media, the author fostered a sense of community. Community is increasingly important in academia, with a strong academic network supporting one another both in book sales and in future research opportunities.

By combining these elements, these book launches were not just promotional events; they were cultural and community experiences that celebrated the enduring appeal of Lewis Carroll’s work and its relevance to contemporary issues.

What Other Authors Can Learn

Build your successful book launch strategy by considering a few things:

- Choose the Right Setting: Consider the themes of your book and select a location that aligns with its message.

- Create Engaging Programming: Offer a mix of academic discussions, creative performances, and interactive elements where appropriate to appeal to your audience.

- Leverage Social Media: Use social media to build anticipation, share behind-the-scenes content, and connect with readers.

- Collaborate with Experts: Partner with scholars, artists, and industry professionals to enhance the credibility and impact of your launch.

Discover this fascinating book for yourself, and see the wider impact and public interest of this subject here: Alice Through the Looking-Glass – Peter Lang Verlag

For more information on the topic, you can find some great features from the BBC where editor Dr. Franziska E. Kohlt contributed.

BBC In Our Time: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland

BBC History Magazine: Lewis Carroll: maker of wonderlands

This is a co-authored blog that sets out to demonstrate in action what this new book series is all about. It is authored in English by Par Kumaraswami, Director of the Centre for Research on Cuba, University of Nottingham, UK; and in Spanish by Adrian Ludet Arevalo Salazar, doctoral student at the University of Western Ontario, Canada

Why do we need to decolonize Cuban Studies?

The most compelling reason for me is that, for purely economic reasons (which are themselves the result of political choices), Cuban views about Cuba are much less easy to find than non-Cuban views. Without suggesting that one set of views is better, or more accurate, than any other, I think this issue can be summed up in one simple question: ‘Wherever you are from, wherever you live, can you imagine if that place were described almost exclusively via the views, impressions and opinions of outsiders, many of whom have never spent any time in that place? Of course, this would be an absurd situation and yet, this is how Cuban Studies operate in the world.

But there’s more. Increasingly, and especially since the end of the Cold War, there are certain perspectives, approaches and assumptions that dominate in Cuban Studies. These come, quite logically, from the centres of academic power which, more often than not, can be mapped onto the centres of economic power. Then through processes of repetition, habituation and normalisation through repeated citation, they create a hermeneutic circle – a reduced and circular set of views and knowledge – about Cuba. In addition, academic scholarship which is published online has now become so accessible in parts of the world – and itself normalised as the only scholarship available – that many voices, visions, approaches and concepts find themselves in the margins, if not altogether invisible. Thus, decolonizing means all kinds of ways of making visible in an established space such as this new Peter Lang collection those other voices, visions and approaches.

What are our aims with this book series?

As a response to the situation which I describe above – which, being a university teacher of Cuban Studies, I know is more widespread than you might imagine – we intend this book series to shine a light on those methods, subjects and approaches which have remained in, or which have been pushed to, the margins. This might mean a focus on Cuban realities outside Havana or Santiago de Cuba, as is the case with the opening volume in the series on educational participation in Granma province, Cuba. It might mean using methods and concepts that derive not from high theories developed in the Global North, but from Cuba or other contexts in the Global South. To decolonize might mean to go beyond the disciplinary boundaries that were established in the colonial university, or that have been celebrated in the neoliberal university, and instead opt for multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary approaches and methods. It might mean to focus efforts on populations and practices that have traditionally been considered as unimportant or peripheral to scholarship, or have been objectified and classified in what academic work exists as exotic or innocent: the lives and cultures of female, black, indigenous or rural populations. It might mean that academic and creative work, high and low cultural forms, sit together on an equal footing in the same volume, and work in dialogue with one another. Decolonization means celebrating and enabling the ability to listen, to accept and embrace contradiction, to recognise that new methods, new subjects and new ways of representing them can yield new concepts, theories and ideas. Finally, by actively encouraging monographs and edited volumes that are written in English and/or Spanish, the collection provides a new place for Cuban authors to represent their own complex realities and perspectives. Through these processes, we aim to create a space that privileges dialogue, so that many more versions of Cuba enter the public domain.

________________

Perspectivas descolonizadoras desde Cuba

¿Por qué necesitamos descolonizar los estudios cubanos?

La necesidad de establecer narrativas y nuevas miradas fuera de los cauces tradicionales me impulsa a pensar en la descolonización desde otras nuevas perspectivas, me refiero a la descolonización de los estudios cubanos desde las voces que generalmente no se escuchan o quedan simplemente subordinadas a otras voces que, tanto dentro como fuera de Cuba se erigen en las voces hegemónicas. La descolonización parte entonces de entender que no hay una sola Cuba, si no muchas Cubas, una Cuba profunda que requiere analizarla y pensarla desde ella misma y desde sus respectivas realidades y desde los componentes sociales que la habitan. Cuba es una comunidad imaginada por seres humanos habituados a la resistencia y la resiliencia, que abarca no solo ese mundo urbano de las grandes ciudades como La Habana o Santiago de Cuba, sus dos ciudades principales. Es también el mundo de las montañas del oriente del país, o de otras partes de la geografía cubana, de las zonas rurales donde se encuentran proyectos culturales tan fantásticos como la Televisión Serrana. Proyectos culturales realizados en el mismo corazón de las comunidades distantes de la Sierra Maestra, con la participación de sus propios habitantes.

Es decir, la descolonización a la que aspiramos, es una descolonización que parte de los centros teóricos que la han definido como una de las más importantes corrientes de pensamiento contemporáneo, asociada a los estudios subalternos y los estudios decolonizadores, entre otros movimientos intelectuales, para dar paso a una praxis que incorpore a esas voces poco escuchadas en sus propios entornos y procesos sociales, culturales y educativos, que de otra manera quedan como espacios y sujetos sin la suficiente visibilidad que han tenido hasta ahora. Cobran entonces protagonismo las periferias cubanas y sus habitantes, sus realidades y diferentes ambientes de producción material y cultural.

¿Cuáles son nuestros objetivos con esta serie de libros?

Esta serie por tanto busca posicionar no solo nuevos temas y procesos del ámbito cubano, poco tratados o soslayados por los cauces académicos regulares, sino que busca nuevos protagonismos y mecanismos metodológicos y conceptuales, que intentan alejarse del tradicional academicismo occidental para incorporar un poco más los enfoques y praxis del sur global y de la propia experiencia cubana de la periferia.

Queremos en un acto de descolonización real, desde una amplia mirada, aceptar la posibilidad, no solo de nuevas formas de comprender la realidad cubana a partir de estas regiones y estas realidades poco transitadas, si no que, a su vez, incorporar el cúmulo de saberes, métodos y formas expresivas que conforman el universo al que se quiere dar voz y brindarle realmente la experiencia descolonizadora que merece. Por tanto, a los ejes transdisciplinar e interdisciplinar, válidos para esta serie, que permiten enriquecer desde diferentes campos académicos los estudios cubanos, se incorpora una especia de intradisciplinariedad que tiene como epicentro el conocimiento y los fundamentos e ideas que han dado forma a estas comunidades.

Por otra parte, pretendemos que la serie sea un punto de encuentro franco y sincero del conocimiento más amplio posible, donde académicos, personas de la cultura y otros sectores de la sociedad, continúen enriqueciendo esa comunidad pensada e imaginada que es Cuba.

Why I decided to write this book?

As a new lecturer in both FE (further education) and HE (higher education), I found research terminology quite difficult to grasp when doing my own action research project for my Level 7 Postgraduate Diploma in Education and Training. There was almost a decade-long gap between completing my dissertation at undergraduate level, and then doing my postgraduate action research project. It took a while for me to re-acquaint myself with the differences and overlap between terms such as systematic reviews and meta-analysis. There weren’t any books or resources available which made research principles relatable to practice, so I decided to write one.

Potentially many researchers who are conducting action research/ research are in the same position as I was, so the ambition was to help others with my book, ‘A 101 Action Research Guide for Beginners’. It was always daunting not knowing where to begin, and there are probably many action researchers out there who feel the same way, so a book like this, written with the frankness of a Yorkshire person, could be a huge asset to others.

What it offers to readers?

The main premise of the book is to demystify research terminology for those teaching, and completing action research projects. Research terms such as systematic reviews, meta-analysis, primary research, and literature reviews are explained simply, with solid links to practice included (with a STEM and healthcare field focus). A book like this offers a much-needed bridge between research concepts and doing research in the real world.

With those new to research it may be difficult to know where to start. Managing a research project is difficult at times. Having a book to refer to that explores the practical side of research, and explains how to format research proposals and conduct research projects, will be an advantage to both up and coming and experienced researchers. Linking practice and research concepts together in a joined-up manner, rather than considering them as separate entities facilitates readers in gaining a deeper comprehension of research terminology. The book conveys how the researcher tackled issues they faced in their action research project by working with others to overcome obstacles. An action research project conducted in a FE college in West Yorkshire is shared in its entirety. This encompasses the research proposal, ethical considerations for the research project, literature review, methodology, results, results discussion and conclusion/ recommendations; right through to it being published in TES (a UK national magazine for teachers) to provide a bonafide practical research example.

Themes such as ethics and maintaining an unbiased approach in research are explained meaningfully. The book depicts how to structure a research proposal and research project report using a contemporary action research project as a template. The book chronicles the rationale behind the choices in methodology selected, and unscrambles research principles, so it connects with researchers at all levels.

Other areas covered in the book include reflection (with reflective account exemplars), artificial intelligence, and quality assurance. It has a free website with more examples of action research in STEM teaching, to provide supplementary resources to further support the readers.

The book is available here: A 101 Action Research Guide for Beginners – Peter Lang Verlag, and at other online retailers, and may be a welcome gift to researchers at all levels doing research projects at undergraduate or postgraduate level.

Readers can benefit from a 10% discount when using code ARG10, valid until 31 March 2025. Please note that discount codes are not valid in regions with fixed book pricing.

Find it here: https://www.peterlang.com/document/1466014

Good luck to all of you doing research projects!

By Laurel Plapp

Three years after launching the DEI Working Group, we are pleased to have a story to tell about our commitment to a diverse and inclusive publishing program.

Why DEI?

For me, the introduction of a DEI initiative at Peter Lang was an extension of what I had been striving to do as an Acquisitions Editor since I joined the company in 2010. But it also reflected a long-term commitment that was part of my academic career before Peter Lang.

While a PhD student and then Lecturer at the University of California, San Diego, my main aim was to help students think critically about the world around them, including dismantling a worldview guided by the white, patriarchal mainstream. In the “Dimensions of Culture” program, I had the opportunity to educate students about the history of slavery and oppression in America, introduce them to the work of great writers like Gloria Anzaldúa and Leslie Marmon Silko, and break down barriers to talking about gender and sexual identity. I often think back on the texts and themes we taught and how they may have shaped that generation, and what positive effects that may have had on progress, even if that fight takes a while.

These threads influenced the later development of my own courses while a Lecturer at UCSD, where I was tasked with teaching German and comparative literature and film. I created for the first time at UCSD a course on “Multicultural Germany,” giving students access to literature and film created by People of Color and immigrants to Germany. Introducing students to Fatih Akin, Yoko Tawada, May Ayim, Angelina Maccarone and more, we explored themes like transnational and transgender identity, experiences of oppression and resistance, and possibilities of solidarity across ethnic groups in Germany. The aim of the course was to change students’ perspective on what it means to be German and, by extension, what that might mean for their own lives in America.

DEI in Practice

When I joined Peter Lang, I was keen to continue to give voice to the oppressed and dismantle the canon through my work as an Acquisitions Editor. This role gives us a unique opportunity to shape the direction of publications in the fields in which we acquire and, for me, my overriding goal was to transform the program into one that was diverse and inclusive.

Over the past 14 years, I have been launching new series intended to privilege the work of creators from persistently marginalized groups and to shine a light on topics like health and disability, feminist and anti-racist movements, social justice and equality. The series editors and editorial boards I recruited were also intended to reflect equity and inclusion, helping to give scholars from underrepresented groups the chance to have their work reviewed in a fair and unbiased way. Read more about these series in our latest Diversity, Equity and Inclusion catalogue.

I also strive to integrate diverse perspectives throughout the books I publish, regardless of the series. This has become a particular hallmark of books in the series Genre Fiction and Film Companions, where every companion includes texts reflecting international, inclusive, and diverse voices.

DEI Working Group at Peter Lang

Starting the DEI Working Group was, for me, a logical extension of these efforts to diversify our publishing program, integrating these principles into all levels of the company. We launched the group in 2021 to explore both internal and external efforts that we can undertake as a company to encourage a diverse and equitable approach to our work. The central aims of the group are to think about how we are presenting ourselves to our contacts, how we can support contacts of all identities and abilities, and how we can enable more inclusive and diverse publications. The following describes our activities thus far.

Supporting Emerging Scholars

One of the first initiatives of the DEI Working Group was to launch the Emerging Scholars Competition, a reimagining of our long-running Young Scholars Competition. The aim of this new competition was to support early career academics working in fields that have been historically underrepresented, offering them the opportunity to win a prestigious contract for publication through a rigorous review process.

Our competitions in Black Studies (2021), in Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies (2022) and in Indigenous Studies (2023) have resulted in 15 emerging scholars benefiting from contracts for publication. The winner(s) of this year’s competition, in Environmental Humanities, receive a Gold Open Access contract, furthering our efforts to make scholarship accessible to as broad an audience as possible. Planning for our 2025 competition, in Queer Studies, is already underway.

Read more about the Emerging Scholars Competition here.

Changing our Language

The DEI Working Group developed a statement of our commitment to DEI, acknowledging our privileged role as a publisher and recognizing the importance of offering a platform for voices and topics that have gone unheard and unseen. We also recognize the need to continually analyze our own practices and policies and reflect on how these may be affecting our partners both externally and internally. We state our commitment to always strive to do better.

With those aims in mind, we revisited documentation that is sent out to authors, examining the kinds of questions we ask on our proposal and peer review forms to ensure that we are supporting an equitable approach to evaluating the work of scholars in the fields in which we publish.

We have also written an internal DEI Handbook with information for our team about best practice for equitable peer review, building of diverse editorial boards, use of gender-inclusive language, respect for pronoun usage, and more.

These efforts are ongoing by our dedicated team, with the aim of making DEI part of our practice across the entire company.

Lifting up Voices

We are meanwhile pleased to feature on our DEI webpage the voices of our authors, including an annual catalogue with educational resources for DEI practice, books that cover diverse and inclusive subjects and approaches, and series that invite new proposals in these fields.

We welcome authors who wish to take part in our Peter Lang et al. blog by writing about their research, their experiences and their own take on DEI. Recent blog posts have set the stage for these discussions, and we invite all our authors to participate.

We hope you will join us on this journey, whether by entering our Emerging Scholars Competition, becoming a peer reviewer, or coming to us with a new book proposal. We always welcome new book proposals and series on DEI topics and scholars from diverse backgrounds. Please reach out to us at editorial@peterlang.com or via our webform. We look forward to hearing from you.

en

en  fr

fr