Number Names

The Magic Square Divination of Cai Chen 蔡沈 (1167-1230)

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Numbers

- A. The Luoshu Magic Square

- B. Number and Number Sets

- C. Cyclical Template of 81 Nodes Rendered as Square Matrix

- D. Structure of the 81 Number Name Matrices

- E. Structure of the 81 Matrix Suite

- F. Summary of Rules of Construction for the 81 Matrix Suite

- G. Architecture and Meaning in the 81 Matrix Suite

- H. Probabilities of Occurrence Among the Luck Schedule Terms

- I. Bias Toward Positive Outcomes in 12th-Century Divination Systems

- 2 Images

- A. Chart of the 81 Numbers

- B. The Language of Cai Chen’s Number Names

- C. The Set of Number Names

- D. The Agricultural Calendar in the Placement and Diction of Number Names

- E. Allusions to the Yijing and Other Classic Literature

- F. Qualities and Discipline of the Noble-Minded Person

- G. Architecture of the Images

- Conclusion: The Numbers Say …

- Appendix I Cai Chen’s Songshi Biography

- Appendix II Bibliographic Note

- Appendix III The “Hongfan School”

- Appendix IV Hongfan Divination Method

- Appendix V Glossary of Yijing Hexagram and Commentary Names

- Appendix VI Glossary of Chinese Names and Terms

- Selected Bibliography

- INDEX

Figures

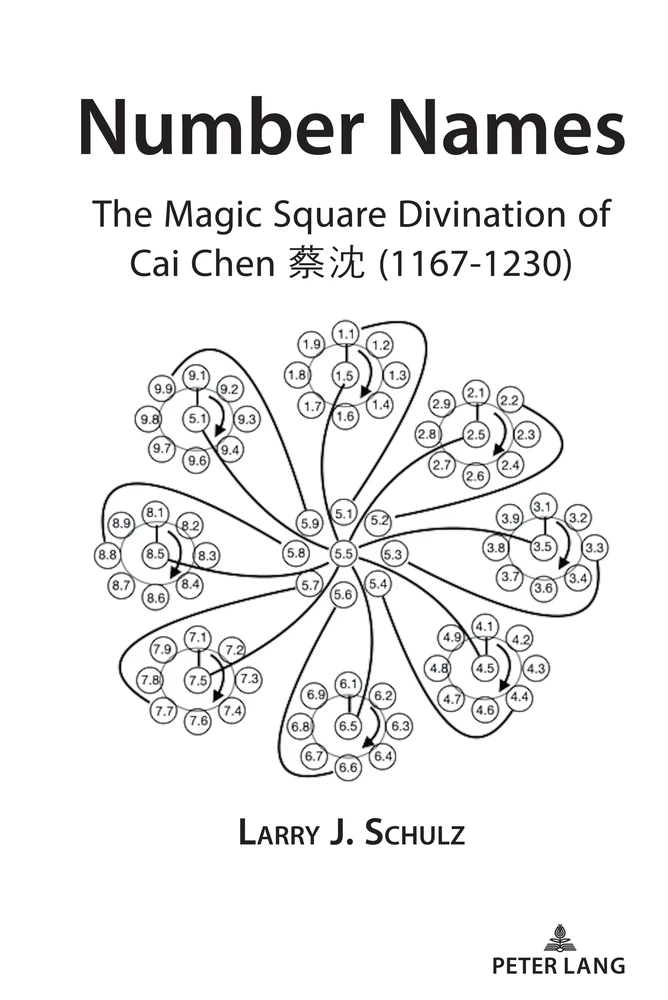

Figure 1.1:Chart of the Eight Numbers in Circular Flow (bashu zhouliutu 八数周流图)

Figure 1.2:Basic -3, -3, +1 Replacement Formula in Luoshu Terms

Figure 1.3:Nine by Nine Circular Number Graph

Figure 1.4:Nine by Nine Numbers in Rows Chart (left); Conversion to Arabic Numerals (right)

Tables

Table 1.1:Luoshu Configuration

Table 1.2:Order 9 Magic Square in Yang Hui, Xuguzhaiqi suanfa

Table 1.3:Cammann’s Proposed Proto-Order 9 Magic Square

Table 1.4:Luck Schedule Terms in Alpha and Numeric

Table 1.5:Numeric Luck Schedule Matrix

Table 1.6:Luck Schedule Column Replacement Pattern

Table 1.7:Quadrant Detail of Luck Schedule Column Replacement Strategy

Table 1.8:Counting Rod Numerals 1–9

Table 1.11:1.5 Straightness Matrix

Table 1.12:2.1 Achievement Matrix

Table 1.13:2.5 Constancy Matrix

Table 1.14:Matrix Family N, Cell 1.1 Left-Hand Term

Table 1.15:5.1 Abundance Matrix

Table 1.17:Distribution of Terms in 81 Number Name Spectrums

Table 1.18:Positive and Negative Qualities of Luck Schedule Terms

←xi | xii→Table 1.19:Frequency of Luck Schedule Terms

Table 2.1:Number Names in Chinese

Table 2.2:Number Names in English

Table 2.3:Antonyms Among Number Names

Aknowledgments

I would like to thank: Xia Shihua 夏世华, the translator-editor of my “Zhouyi” guaxuwenti zonglun 〈周易〉卦序问题综论,for providing a survey of contemporary research in Chinese on Cai Chen; mathematician Ryan Hutchinson for offering useful comments on the "Numbers" chapter; and Edward L. Shaughnessy, my touchstone on the early history of the Yijing, for making observations that helped shape the "Images" chapter. Thanks to Peter Lang Publishing for bringing this long obscure work to light and to the editorial staff there for their professional assistance in shepherding the book through the publication process. And, as always I am grateful to the love of my life, Barbara, for thoughts on the roughest of drafts and a sympathetic ear to teatime discourses on the idiosyncratic scholars who produced traditional Chinese number theory.

Introduction

When the NeoConfucian patriarch Zhu Xi 朱熹 (1130–1200) endorsed the set of graphic depictions and divination lore that became the opening chapter in official editions of the Yijing,1 he effectively sanctioned an option for creative expression within what would otherwise become a stifling orthodoxy—an orthodoxy based to a great extent on Zhu Xi’s other pronouncements. His Yijing graphics include two visualizations of numerical relationships among the first ten digits, called the Hetu 河圖 and Luoshu 洛書, two arrangements of the eight trigrams (bagua 八卦), and several constructs of the 64 hexagrams in square and round arrays.2 The material also includes Zhu Xi’s reconstruction of the yarrow stalk-sorting divination method, and together these graphics and numeric speculations became primary sources for the development of what has been called the “Image and Number School (xiangshupai 象數派).”3

The new possibilities seen in the graphics Zhuxi selected led to a proliferation of ideas expressed in matrices and charts of various designs that in turn underwrote speculation about relationships among numerical structures and the verbal images of the divination texts in the Yijing. So powerful could these relationships be in explaining the Yijing’s obscure wording that Image- and Number-type explanations came to be given equal prominence with textual exegesis by the time Lai Zhide (來知德, 1525–1604), the best known of the later Image and Number proponents, wrote his Yijing commentary.4 Lai ←xv | xvi→and other scholars associated with this “school” tended to be independent, and many of them ignored or were dismissive of earlier thinkers;5 their ideas, though sharing numerous fundamental concepts, did not coalesce into a unified theoretical framework. My earlier research has aimed at pulling together their number theory into a coherent whole, comprising the structure of the sequence in which the 64 hexagrams are presented in the Yijing and calendric associations prominent in the Han Dynasty, as well as Zhu Xi’s graphics and their successors.6

The latter were introduced for the most part by Shao Yong 邵雍 (1011–1077), who is said to have taken some graphic structures from a line of transmission dating back to Chen Tuan 陳摶 (871?–989), a shadowy character on the cusp between Daoism and Confucianism.7 Shao also constructed his own depictions, including an 8 x 8 square hexagram matrix surrounded by a related circular array that will play a key role in Part I below. Shao and other Image and Number proponents thought in terms of a circular template betokening the annual solar cycle. They saw the trigrams and hexagrams as numbers marking geometric nodes on that template, which also accommodated calendrical sets of 4 seasons, 12 months (both solar and lunar), 60 “stem and branch” duodecimal counters, 365 days, spatial sets of four or eight directions, the Five Phases (wuxing 五行) of fengshui (風水) and medical theory, and other imagistic sets. Yijing lore, like strings of associations from the Shuogua 說卦, one of the “Ten Wings (shiyi 十翼)”—first order commentaries thought to have been written by Kongzi (孔子, Confucius)—could also be located along the template to enrich the correspondences at the nodes. Any member of any set falling on or near the same node could serve as analogs; thus, verbal images such as trigram and hexagram names were taken to reflect the underlying numeric.

From this template, then, one could trace the association of a number—like a trigram or duodecimal counter—with a verbal image. The trigram zhen ☳, for example, might occur at the vernal equinox, 90º along the circumference from the winter solstice at 0º. There, also, was located the duodecimal term mao 卯, which is thus linked to the trigram zhen and all its synonyms: the east, springtime, thunder, action, wood, etc. Of course, the fascination with these depictions, as with the Yijing itself, was their assumed efficacy in supporting divination, which involved another complex line of numerical thinking (as discussed in Appendix IV). Thus, divination might be supposed to “work” because its random operation produced a number that intercepted the seasonal template, depicting the current interrelationship of numerical cycles and their unfolding implications in verbal analogs.8←xvi | xvii→

I had not, however, come across an Image and Number scholar who expressed such a “hybrid” theory in its entirety. Then I chanced upon the Master Plan Supreme Pivot Inner Writings (Hongfan huangji neipian 洪範皇極內篇)9 of Cai Chen 蔡沈 (t. Zhongmo 仲默, h. Jiufeng 九峰 1167–1230),10 a first-generation disciple of Zhu Xi. Cai Chen did not work from Yijing-related binary figures; instead, he evolved an original system from his own reading of the “Hongfan,” a chapter in one of the other Confucian Classics, the Shujing 書經. This allowed him to build from scratch, drawing on aspects of the Yijing tradition—its wording, commentaries, and philosophical associations—while rationalizing many of its anomalies. In this, he followed Shao Yong, whose sprawling Huangji jingshi shu 皇極經世書 took Yijing binary thinking in unprecedented directions, presenting an intricate model of recurring temporal epochs laid out with reference to the meanings of Yijing hexagrams. The “Supreme Pivot (huangji)” in the title of Cai’s book is in part homage to Shao’s invention. What resulted in Cai’s case was a set of 81 “Number Names”11 that ran in sequence around a circular template. Each Name was taken as the function of one of an integrated suite of 81 numerical 9 x 9 matrices, and for each he proposed divination readings (called “legends” herein). These legends are relatively intelligible, in contrast to Yijing texts, and Cai also proposed a rationalized yarrow stalk divination method to replace the inordinately complex Yijing method as it was understood by Zhu Xi and others. This method yielded in divination a “Number Name (shuming 數名)” and a secondary straightforward judgement of its good or bad fortune.

Cai said that his matrices were derived from the Luoshu diagram, which he claimed to discover in the wording of the Hongfan. The Luoshu is recognized by historians of mathematics as the earliest expression of a normal magic square of order 3. Although it appears to have a history that may reach back to the 2nd century BCE., the Luoshu was first described in the work of Cai’s younger contemporary, the mathematician Yang Hui 楊輝 (d. 1298 CE).12 Schuyler Cammann argued that in discussing what Yang Hui called “vertical and horizontal charts (zonghengtu 縱橫圖), Yang “admitted that he was merely handing down the works of men of old, and he made no claim to being any sort of an innovator himself.”13 Nor did Cammann think Yang Hui fully understood what he was passing on, being on the declining slope of the understanding of magic squares in China: “although the early development of magic squares in China was indeed impressive, judging from the results that have come down to us, this must have reached its height some time before 1275, when Yang Hui published his examples of the early work.”14←xvii | xviii→

Neither Yang Hui nor Cammann mentions Cai Chen’s suite of matrices, nor does Joseph Needham, in Science and Civilization in China, or Wu Wenjun in his compendium on Chinese mathematics,15 but they may well have been the “height” of the art of magic square theory reached “before 1275.” With no antecedents of comparable complexity,16 they emerged suddenly half a century before Yang’s book, and, though they attracted some Image and Number enthusiasts who used them to their own ends—a so-called “Hongfan School (Hongfanpai 洪範派),”17 the structure of the matrices was not fully explained either by their author or later scholars. As systematic theoretical work on magic squares only began with 17th-century European mathematicians, Cai’s creation has thus remained an unexplored milestone in the history of mathematics—an oversight that the present study seeks to address.

Cai saw “Number (shu 數)” as the abstract complement to the Yijing’s concrete images (xiang 象)—verbal expressions associated with its hexagrams and lines (yao 爻). Similarly, his work recasts the Yijing’s underlying concepts in an alternate numerical framework and offers what is essentially a commentary on them. The Yijing’s images arise, this perspective suggests, from the demarcations that language assigns in expressing the periodicity of natural phenomena. The seasonal round flows from its Origin—the first of his Number Names—at the winter solstice through 81 nodes to reach its End—the Name of the 81st—and immediately, with no interruption, begins again and repeats endlessly. Each Name is expressed numerically by a pair of the digits one to nine just as each Yijing hexagram is taken to reflect the interplay of two trigrams. The latter idea was superimposed on the original Yijing text by the first order commentaries; in Cai’s system, it is fully integrated from the outset.

Cai explicitly employs the circular template’s seasonal analogy as his transition from pure number to verbal imagery. The template is “Pattern” (li 理, often translated “Principle”), the signature NeoConfucian philosophical concept.18 Cai said, “Number is the temporal order of Pattern; words are the meaning of Number.”19 In itself unseen, Pattern is manifest and comprehensible in the life cycles of all phenomena, collectively and individually. Cai takes the numerical representation of Pattern from its circular archetype to a square by transposing its sequential nonary segments to the columns of a 9 x 9 matrix. He then explores the relationships exposed by this juxtaposition as Shao Yong did in his 8x8 hexagram matrix.20 Cai presented 81 successive permutations of the original graphic that display a unique numerical structure for each Number Name node. His Number Names are the fundamental “words” that are “the meanings of Number” at each node, and Cai also expanded on ←xviii | xix→them in the legends attached to each Name. However, he insisted that all numbers are in effect two numbers, the odd and even of yang 陽 and yin 陰, which represented the universal cyclical dynamic of extension and intension. In this way, he kept his base nine approach in synchronization with the binary basis of all Image and Number thinking.

Details

- Pages

- XX, 188

- Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433186844

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433186851

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433186868

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433185991

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18215

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (February)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2022. XX, 188 pp., 6 b/w ill., 24 tables.