What Is Sustainable Journalism?

Integrating the Environmental, Social, and Economic Challenges of Journalism

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- What Is Sustainable Journalism?: An Introduction (Peter Berglez, Ulrika Olausson, and Mart OTS)

- Introduction

- Challenge 1

- Challenge 2

- A Dual Relation Between the Crises?

- The Global Sustainability Crises

- The Environmental Dimension

- The Economic Dimension

- The Social Dimension

- Reconciling the Three Sustainability Dimensions

- The Journalism Crisis

- Sustainable Journalism

- Notes

- References

- Contributions

- Environment in Focus

- Society in Focus

- Economy in Focus

- Part One: Environment in Focus

- Chapter One: Quick and Dirty News: The Prospect for More Sustainable Journalism (Justin Lewis)

- Introduction

- Obsolescent News

- The Celebration of Economic Growth

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Two: Making Journalism Sustainable/Sustaining the Environmental Costs of Journalism (Richard Maxwell and Toby Miller)

- Contexts, Responses, and Shoddy Metaphors

- Greening Journalism, Past and Present

- What Can be Done?

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Three: The Ecomodernists: Journalists Reimagining a Sustainable Future (Declan Fahy and Matthew C. Nisbet)

- Introduction

- Ecomodernism and Environmental Journalism

- Ecomodernists as Knowledge Brokers

- Ecomodernists as Policy Brokers

- Ecomodernists as Dialogue Brokers

- Conclusion: Ecomodernist Journalists as Levers of Change

- References

- Chapter Four: Post-normal Journalism: Climate Journalism and Its Changing Contribution to an Unsustainable Debate (Michael Brüggemann)

- Introduction

- The Analytical Framework: Post-Normal Journalism

- Empirical Findings on Journalism’s Role in the Debate on Climate Change

- Limits of Post-Normal Journalism and Implications for the Sustainability of the Climate Debate

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Five: Environmental Journalism and Environmental Sustainability in Southeast Asia (Yan Wah Leung, Edson C. Tandoc JR., and Shirley S. HO)

- Introduction

- Threats to Environmental Sustainability

- Impact of Environmental Journalism

- Threats to Environmental Journalism in Southeast Asia

- Media corruption

- Press freedom

- Asian values

- Quality of News Coverage

- Sustaining Environmental Journalism in Southeast Asia

- The Rise of Citizen Journalism

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter Six: Student Content Production of Climate Communications (Beth Osnes, Rebecca Safran, and Maxwell Boykoff)

- Introduction

- Going ‘Inside the Greenhouse’

- Courses

- Events

- Internships

- Individual Student Highlight

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Part Two: Society in Focus

- Chapter Seven: Journalism and Democracy: Towards a Sustainable Future (Pieter Maeseele and Daniëlle Raeijmaekers)

- Introduction

- Journalism and Social Order

- Journalism and the Neoliberal Order

- The Logics of Journalism

- The Logic of Professionalism

- The Logic of Commercialization

- Liberal Ideals

- Liberalism’s Blind Spot

- The Logic of Rationality

- The Logic of Contestation

- The Problem of Objectivity

- Contestation and Subjectivity

- Alternative Discursive Spaces

- Discussion

- Note

- References

- Chapter Eight: News Journalism for Global Sustainability?: On the Problems with Reification and Othering when Reporting on Social Inequality (Ernesto Abalo)

- Introduction

- Social Inequality and Sustainability

- Inequality, Journalism and Ideology

- Reification and Othering when Reporting on Social Inequality

- Naturalizing Inequality and Othering its Victims

- Reifying class struggle

- Concluding Remarks: Towards a News Journalism for Global Sustainability?

- Note

- References

- Chapter Nine: News-savvy Kids and the Sustainability of Journalism (Ebba Sundin)

- Introduction

- Social Responsibility Concerns

- News Media for Children

- The Nordic Trend

- Children’s News and Sustainable Journalism

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Ten: News Users’ (Dis)trust in Media Performance: Challenges to Sustainable Journalism in Times of Xenophobia (Susanne M. Almgren)

- Introduction

- Values at Work in (Sustainable?) Journalism

- A Thematic Text Analysis of User Comments

- The Themes of Conflict

- “Elites” versus “Commoners”

- Rules and Roles in Public Service and Commercial Media

- Representation versus Excommunication

- Journalists’ Political Views Compared to the Public

- Crime and Transgressions

- Discussion and Conclusions

- References

- Chapter Eleven: Sustaining Spaces, Patrolling Borders: News Coverage of Migrating Peoples (Mike Gasher)

- Mapping the World: Journalism as a Spatial Practice

- Mapping the World: Journalism as a Representational Practice

- A Place Called Canada

- A Change in Government: A Return to Canadian Values?

- Naturalizing Canadian Culture

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Twelve: Sustainable War Journalism and International Public Law (Stig A. Nohrstedt and Rune Ottosen)

- Introduction

- Current Trends in Warfare, Media Development and War Journalism

- Globalization and the Crisis of Human Rights

- New Wars

- Mediatization of War

- Martialization of War Journalism

- Shortcomings in how Violations of International Public Law (IPL) are Reported by War Journalism

- The Syrian War and Daesh Terror—Journalists in Harm’s Way

- Media Challenges

- Are There Lessons to Be Learned from Libya After All?

- Media’s Reporting from the Drone War—Selective and Biased

- Conclusions

- References

- Part Three: Economy in Focus

- Chapter Thirteen: A Global Media Resource Model: Understanding News Media Viability Under Varying Environmental Conditions (C. Ann Hollifield and Laura Schneider)

- The 21st Century Media Environment

- Methodology Underlying this Project

- Assumptions of Research on Media Competition & Media Performance

- A Resource-Based Approach to Understanding Media Competition

- Niche Theory and Media Viability

- Preliminary Taxonomy of Global Media Resource Issues

- Insights from Interviews on Media Viability

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Fourteen: Monitoring Media Sustainability: Economic and Business Revisions to Development Indicators (Robert G. Picard)

- Western Media Development Organizations and their Approaches

- A New View of Media Development

- A Maturation of the UNESCO Approach

- New Business/Financial Sustainability Indicators

- Concluding Remarks

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Fifteen: Mapping the World’s Digital Media Ecosystem: The Quest for Sustainability (James Breiner)

- Introduction

- Mapping the Digital Ecosystem Around the World

- Italy, France, Germany

- Spain

- Holland

- Latin America

- Anglophone Startups

- Digital Sustainability in the U.K.

- Digital Sustainability in the U.S.

- Entrepreneurial Model: Texas Tribune

- Conclusions

- Training

- Funding the Next Generation

- References

- Chapter Sixteen: The Sustainability of Native Advertising: Organizational Perspectives on the Blurring of the Boundary between Editorial and Commercial Content in Contemporary Media (Fredrik Stiernstedt)

- Introduction

- Native Advertising, Media Organizations and the Corporate Form of Capitalist Cultural Production

- The Organization of Media Production

- Entry Points

- “Easier, Funnier and More Effective Business”

- The Media House as an Organizational Form

- The Media House as an Idea

- The Media House as a Building

- Apathy, Resistance, Dissidence

- Conclusion

- Note

- References

- Interviews

- Chapter Seventeen: Managing for Sustainable Journalism Under Authoritarianism: Innovative Business Models Aimed at Good Practice (Naomi Sakr)

- SDGS and “Fundamental Freedoms”

- In Search of Qualitative Criteria

- Revenue Streams and Business Models

- Management Frameworks

- Audience Engagement

- Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Eighteen: Sustainable Journalism?: An Approach to New Ethics Management to Achieve Competitive Advantages (Anke Trommershausen)

- Introduction

- What is Meant by Sustainable Journalism?

- Obstacles to Sustainable Journalism in Times of Digital Transformation and Organizational Change

- Influence of Technology

- A New Understanding of Organization and Management in Times of Uncertainty

- New Organizational Preconditions for Good Ethical Choices in Journalism

- Realizing Sustainable Journalism as a Competitive Advantage Through a Practice Approach

- Ethics-as-Practice

- Realizing Sustainable Journalism as a Competitive Advantage

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Nineteen: The Socio-local Newspaper: Creating a Sustainable Future for the Legacy Provincial News Industry (Rachel Matthews)

- Introduction

- The Good of the Community and the Business of Newspapers

- Laying Claim to Community Benefit while Undermining that Role

- Rethinking Newspaper Funding to Shore up the Good of the Community

- The Economic Sustainability of the Socio-Local Newspaper

- Conclusion: We all have a Stake in the Socio-Local Newspaper

- Notes

- References

- Chapter Twenty: Structural Collapse: The American Journalism Crisis and the Search for a Sustainable Future (Victor Pickard)

- The Economic Roots of the American Journalism Crisis

- Social Implications of the Crisis

- Making Sense of the Crisis

- Journalism Crisis = Market Failure

- Alternative Trajectories

- Removing Profit From News

- Notes

- References

- Authors

Though sustainability is in fashion among both practitioners and academics, it is still in its conceptual infancy. In the field of journalism studies there is a great need to explore its various dimensions and potential applications. That is where we believe that this volume will open up new venues for academic research and debate.

The idea for this anthology came from the recently established research program in Sustainable Journalism at Jönköping University, Sweden, an initiative originally deriving from Ulrika Olausson. As in the case with this book, the object of the program is to establish a long-term dialogue between researchers who are, in quite different ways, engaged in the future challenges of journalism, be it from an economic, social or environmental point of view. Future-oriented media research is practiced worldwide, but what makes Jönköping University a particularly good place for doing research about sustainability in journalism is the presence of, and short distance between, two media departments: a media and communication department, belonging to the School of Education and Communication, and a media economic department (MMTC), which is connected to Jönköping International Business School and headed by Mart Ots. This anthology stems from a collaboration between these two departments, which at least partly represent two different languages/discourses on the same topic (media and journalism). It is our conviction that in order to boost dynamic research on the future of journalism, media and communication scholars and scholars from the media business field need to approach each other. ← ix | x →

The chapters of this book have been authored by scholars across the globe. We would like to thank them for their highly valuable and important contributions to the understanding of journalism from a sustainability perspective. Hopefully, this book can serve as a starting point for even more integral approaches to journalism research, bringing the integration of the environmental, social and economic challenges of journalism to the next level.

Peter Berglez, Ulrika Olausson and Mart Ots

Jönköping, 23 March 2017

What Is Sustainable Journalism?

INTRODUCTION

This edited volume, which elaborates on the idea and concept of sustainable journalism, is the result of a perceived lack of integral research approaches to journalism and sustainable development. Thirty years ago, in 1987, Our Common Future, the report from the UN World Commission on Environment and Development (also known as the Brundtland Report), pointed out economic growth, environmental protection and social equality as the three main pillars of a sustainable development. These pillars are intertwined, interdependent, and need to be balanced and reconciled. Economic growth is in this sense necessary for a developing world, but a one-sided focus on economy will eventually lead to a world that is both socially and environmentally poorer. Obviously, the issue of sustainability has not been absent from the field of journalism research; on the contrary, there is plenty of research focusing on journalism and environmental sustainability (e.g., climate change, fracking), social sustainability (e.g., democratic and political participation, poverty, inequality), and economic sustainability (e.g., ownership, commercialization, business models). However, where journalism studies traditionally treat these three aspects of sustainability disjointedly, this book attempts to pull them closer together and integrally approach sustainable development in its environmental, social and economic sense.

The book departs from the premise that journalism has a role to play in global sustainable development—to inform, investigate and to educate in ways that ← xi | xii → reconcile the three pillars. It also raises questions about the internal sustainability of journalism itself, asking how its rampant need for economically sustainable business models can possibly be negotiated with its social and environmental obligations and impacts. In this way, the concept of sustainable journalism interlinks two current sustainability challenges that are of great theoretical relevance and in urgent need of empirical research.

Challenge 1

This refers to the ongoing series of unprecedented global crises caused by economic and technological globalization and their social, political, cultural and environmental impacts (Cottle 2009; Becker, Jahn and Stiess 1999). Modernity brought with it not only economic wealth (for some people), but also quite a few unwanted side-effects in the form of global risks and crises (Beck 2006). These risks entail, for instance, climate change, loss of biodiversity, acidification of the world’s oceans, and depletion of important natural resources—all of which are negatively affecting the ecosystem. Additionally, the world is still plagued with diverse forms of social crises: one out of five people on earth are still poor; the gap between rich and poor both within nation-states and globally has not diminished; financial meltdowns, democratic collapses and armed conflicts still occur; and, despite various positive reports from the WHO on, for example, increase in average life expectancy around the world, preventable human suffering persists. These crises amount to severe obstacles for an ecologically and socially sustainable society, and constitute serious challenges for the realization of the UN’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including its seventeen Sustainable Development Goals.1 When it comes to explaining the highly worrying state of the world, Held and McGrew (2004), amongst others, particularly point out the role of neoliberalism and uncontrolled market capitalism. Increasing gaps between wealthy and poor populations, both at the global, national and local levels, tend to lead to increasing distrust in society’s institutions among the losers in this development (Rothstein 2011), in which politics and public authorities become ever more associated with elitism and distance towards “ordinary people”.

By dividing states and peoples it engenders a deepening fragmentation of world order and societies, generating the conditions for a more unstable world. Unless economic globalization is tamed, so the argument goes, a new barbarism will prevail as poverty, social exclusion and social conflict envelop the world. What is required is a new global ethic which recognizes “a duty of care” beyond borders, as well as within them, and a new global deal between the rich and the poor. (Held and McGrew 2004: 30)

People and governments worldwide might respond to this in constructive ways, in terms of striving for the above-mentioned goals set up by the UN and its member ← xii | xiii → states; fulfilling signed agreements, such as the COP 21 Paris Agreement on reducing CO2 emissions among the world’s countries and the C40 deal among world cities; implementing relevant policies at the national and local level; and supporting and pushing forward innovations for the sake of a more sustainable future for the many. Or, the unforeseen and even somewhat apocalyptic future could be met with increasing cultural anxiety, post-factual reasoning and ideological nostalgia, paving the way for what Nohrstedt (2010) has vigorously termed the “threat society,” which Donald Trump’s presidential victory in the US seems to exemplify.

Challenge 2

The second challenge is of a totally different magnitude and character, as it “only” involves the development and survival of a particular institution, that is, professional journalism. It is commonplace among both practitioners and academics in the media sector today to bewail the current crisis of journalism, which stems from factors such as shrinking advertising revenues, collapsing share prices, falling news consumption, and rising unemployment among journalists particularly in a US and European context (cf. Leung, Tandoc and Ho; Sakr, both in this volume). In today’s digital media landscape, encompassing a vast array of technological options, competition is fierce when it comes to the distribution of information. The number of information brokers has multiplied, and the rapidity by which information can spread on social media such as Facebook and Twitter, or via various wire services, is virtually impossible to compete with. Along with this, the emergence of user-generated content and citizen journalism calls into question the very need for the professional journalist (Lewis, Kaufhold and Lasorsa 2010; Steensen 2011; cf. Osnes, Safran and Boykoff in this volume). The journalism crisis is at the same time a business crisis (pertaining to the economics, organization and technology of the media industry), and a discursive crisis (pertaining to content), raising concerns about journalism’s future democratic role in society (De Mateo 2010) as well as urging journalism scholars to return to rudimentary questions such as “What is journalism? and “Who is a journalist” (Franklin 2014: 475).

Arguably, traditional quality journalism is stuck in a logic which has already been colonized and refined by numerous amateur media and citizen journalists online. At least some of the vital functions of traditional media, such as breaking news, have been overtaken by millions of potential actors and their digital devices. This calls for a revitalization and updating of mainstream media concerning its mission in society and its business models. Furthermore, just like other industries facing a similar situation (the music and film industries, for example), professional journalism needs to look towards practices of storytelling which are out of epistemological reach for non-professional media practitioners. Today’s journalism ← xiii | xiv → developed in parallel with the rise and expansion of the modern nation-state (Berglez 2013: 51–57). Thus, what has historically been a sustainable model for journalism, both in commercial and democratic respects, is its role as the watchdog of national politics and elites (that is, as fourth estate), and its contribution to the symbolic production of an imagined national community and identity when serving as the sociocultural glue holding nation-state institutions—including the relation between institutions and citizens—together (Anderson 1991). This will be an important dimension of professional journalism also in the future but, simultaneously, there is a complex globalizing reality that seems to have outstripped journalism and its traditional nation-state rationale (Beck 2006: 27–28). In order to catch up with cross-national reality, journalism needs to update its business models as well as the ways in which social reality is covered. Or, simply put: professional journalism needs to invent its own paradigm shift.

A Dual Relation Between the Crises?

Our suggestion is that the global sustainability challenges of late modern society and its new complexities might show a way out and give rise to a “rebirth” of professional quality journalism, both from a business perspective (to find its way back to the consumers) and discursively (practices of reporting). Following this line of thought, vigorous journalism is a prerequisite for meeting the global sustainability crises, but it is also true that, in order to remain a socially and democratically relevant institution, journalism is in dire need of internalizing and integrating these crises in their entirety.

More precisely, this book is premised on the theoretical assumption that there is a mutual dependency between the global sustainability challenge and the journalism challenge. Admittedly, journalism might be viewed as a natural part of society’s different problems due to its commercialized and stereotypical (Lippmann 1922) ways of representing it. Nonetheless, at least qualitative journalism has a pivotal role in the overall sustainable development of society since it, at least potentially, contributes greatly to the understanding, and hence the handling, of challenges such as environmental problems, social inequality, armed conflicts, and financial crises. In order to put pressure on politicians and the market as well as to engage citizens politically (Carvalho, van Wessel and Maeseele 2017), advanced journalism that produces engaging and relevant stories about, for instance, climate change or internet surveillance is needed. What is also required is a journalism that develops its competence to engage in the antagonism and disagreements between the peoples, nations, regions, organizations, etc., that the path towards more sustainability, by necessity, involve (see Maeseele and Raeijmaekers in this volume; Olausson 2007; Vallance, Perkins and Dixon 2011).

In turn, addressing the new conditions of journalism—by seriously responding to the sustainability challenges with high-quality, in-depth coverage as well as ← xiv | xv → robust business models, technology, education and organizations that take these challenges into account—is a prerequisite for the sustainability, that is, the long-term survival of professional journalism itself; at least for the kind of journalism ideal that developed in modern society.

Accordingly, the task for media and journalism scholars is threefold: first, to highlight integral perspectives by commencing a dialogue between scholars and researchers engaged in either the environmental, social or economic challenges of journalism; second, to conduct theoretical and empirical studies that examine the underlying barriers to a journalism that is better “prepared for the future” (a future which is, however, already here through problems such as climate change) as well as already existing examples of well-working forms of sustainable journalism; third, to further develop academic input on how to implement a sustainable journalism, both in terms of business models and in terms of journalistic practice, which could be addressed to and discussed with industry representatives and other relevant stakeholders.

The rest of this chapter is structured as follows: a theoretical description of the sustainability concept (including its environmental, social and economic dimensions) is followed by a presentation of the general condition of contemporary journalism and its crisis situation, at least as it appears in many Western societies. The chapter is concluded with a discussion on the concept of sustainable journalism; its relation to other types of journalistic practices that potentially contribute to a sustainable future such as, for example, global journalism; and its usefulness as theoretical perspective in an academic context as well as a potential practice among journalists and media-workers.

THE GLOBAL SUSTAINABILITY CRISES

Sustainable development

A sustainable global society founded on respect for nature, universal human rights, economic justice, and a culture of peace.2

Sustainable development calls for concerted efforts towards building an inclusive, sustainable and resilient future for people and planet.3

Sustainable development is development that can meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.4

Notwithstanding numerous definitions such as those above, it is no exaggeration to claim that the concept of sustainability—or sustainable development—is one of the most debated, elusive and ambiguous. For some scholars it “appears to be an over-used, misunderstood phrase” (Mawhinney 2002: 5); others claim that there ← xv | xvi → is hardly any consensus on sustainability beyond the notion that there is no shared understanding (Becker, Jahn and Stiess 1999); while others are more optimistic about a collective view on its essential characteristics, for instance that sustainability is an open-ended process, that it is both universal and context-dependent as well as a challenge to conventional thinking and practice (Gibson 2005). Other aspects of sustainable development, which are hard to contest, include its long-standing nature and global ramifications (Elliot 2013).

The concept of sustainable development is interdisciplinary and has been evolving since the early 1970s when interest in environmental quality began to rise. The original emphasis on economic development and environmental protection has successively broadened to also include social concerns (Vallance, Perkins and Dixon 2011), which mirrors the nature of today’s global challenges that interlink people in various parts of the world through connected crises in climate, energy, economy, poverty and social injustice (Elliot 2013). In this way, sustainable development is commonly described as composed by the interrelated environmental, economic, and social dimensions, referred to as the “triple bottom line” (Rogers, Jalal and Boyd 2008).

The Environmental Dimension

The environmental dimension is often the one that comes first to mind when talking about sustainability, and early contributions to the debate on sustainable development came from the environmental disciplines (Elliot 2013). Essentially, this dimension deals with the resilience and robustness of biological and physical systems (UNEP, 2011), and is often regarded as the overall framework within which the other two dimensions are included and subordinate. It is the ecological carrying capacity that determines what is possible to achieve, economically and socially (Elliot 2013).

In 2009, Rockström et al. identified a set of nine so-called planetary boundaries, which illustrate the main ecological concerns of sustainable development and have been influential in environmental policy-making. The nine boundaries include stratospheric ozone layer; biodiversity loss and extinctions; chemicals dispersion; climate change; ocean acidification; freshwater consumption and the global hydrological cycle; land system change; nitrogen and phosphorus inputs to the biosphere and oceans; and atmospheric aerosol loading. The original planetary boundaries have been criticized by some and revised by the authors themselves (Steffen et al. 2015), but the main message remains: within these boundaries, humanity can continue to develop economically and socially, while crossing them would cause irreversible environmental changes affecting the life conditions for humanity. Some of these environmental hazards, such as ozone ← xvi | xvii → depletion, currently seem to stay within their boundaries, while we are in the danger zone regarding others, such as biodiversity loss and climate change.5

All human activity ultimately depends on the carrying capacity and resilience of the ecological systems. When crossing the planetary boundaries, the foundation of the very existence of humans is shaken to its ground (Elliot 2013).

The Economic Dimension

The complex relationship between economic growth and sustainable development has been the subject of continuous disagreement. On the one hand, the two are often regarded as mutually exclusive, and it is assumed that the capitalist logic of never-ending economic growth would inevitably affect environmental and social sustainability negatively, a central leitmotif in Naomi Klein’s 2015 bestseller This Changes Everything, among others (see Abalo; Lewis; Maeseele and Raeijmaekers; Maxwell and Miller, all in this volume). On the other hand, businesses are driven largely by economic motives and there is a consensus among sustainability researchers that in a market economy, business organizations are key actors in the process of achieving sustainable development at the societal level (Schaltegger, Hansen and Lüdeke-Freund, 2016a).

Over the past decades, there has therefore been a growing interest in “sustainable business models” (Bocken et al. 2014; Stubbs and Cocklin 2008). That is, how firms may organize their operations in ways that reduce negative societal effects (or create positive ones), while at the same time maintaining, or even improving, their competitive position. The inclusion of socio-environmental aspects into business strategies might be viewed as a commercial strategy through, for instance, energy efficiency and improved public image (Hawken, Lovins and Lovins 1999), and there has been a surge in CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) activities in the business sector.

In this vein, adopting a sustainability “mindset” may radically transform the way firms look at the business they are in (Loorbach and Wijsman 2013). Such a capability to rethink operations in the light of broader societal changes is arguably an important condition for competitive advantage. By anticipating and treating the legal and organizational challenges of sustainability as opportunities rather than threats, firms may propel business innovation to new levels (Nidumolu, Prahalad and Rangaswami 2009; Fahy and Nisbet in this volume).

However, applied to journalism, and adding the challenges of digitization, the situation is not uncomplicated. Whereas research in other sectors discusses how niche entrepreneurs may change markets by entering with sustainability principles at the core of their business models (Schaltegger, Lüdeke-Freund and Hansen 2016b), entrepreneurs in the news industry are often portrayed as the ← xvii | xviii → opposite—threatening sustainability (as defined by legacy media) by competing with lighter news, less fact checking and fewer journalists (if any at all).

The Social Dimension

The social dimension was added to the environment-economy relationship when it successively was acknowledged that nature and culture cannot be viewed as separate entities—people and the environment do not exist isolated from each other. Any significant changes introduced into the environment—changes in the climate, for instance—will likely affect people’s lives, and changes in society—increased urbanization, for instance—have obvious impacts on the natural environment. Hence, sustainable development incorporates the need for a long-term balancing of not only the economic but also the social needs within the limits of the ecological carrying capacity (Rogers, Jalal and Boyd 2008; Vallance, Perkins and Dixon 2011). In this way, the social dimension deals with the sustainable development of social, political and cultural systems, and addresses issues such as peace, security, social and environmental justice, poverty, human rights, political participation, democracy and equality. If concerned institutions provide insufficient support when it comes to these social issues (symbolically, economically, juridically, organizationally, educationally, etc.), sustainability will not be achieved (Rogers, Jalal and Boyd 2008).

At the UN World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002, which established the concept of sustainable development among broader populations, a main concern was the unequal distribution of benefits and costs of economic globalization. These global inequalities were supposed to negatively impact not only the environment but also democracy and future security (Elliot 2013). Since then, the notion of “environmental justice” has gained momentum in the discussions on sustainable development, addressing concerns such as how environmental pollution and devastation as well as environmental resources, etc., are distributed across and affect various parts of society (Elliot 2013).

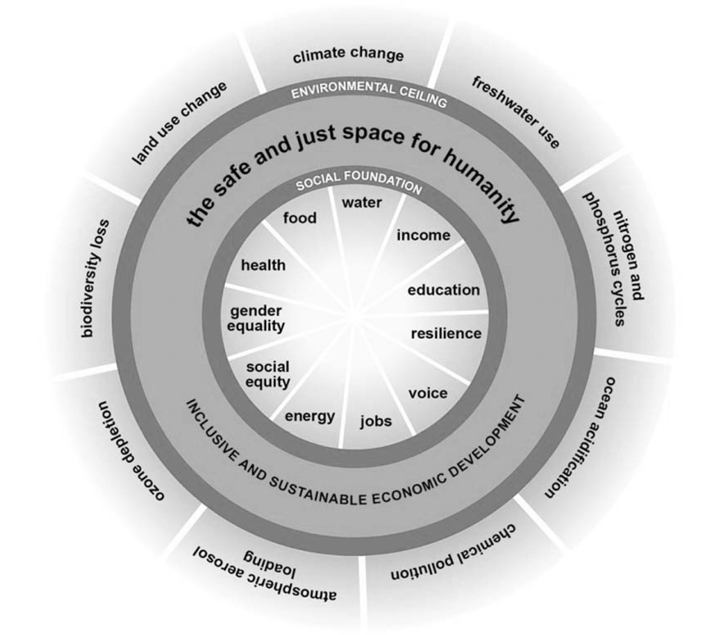

Reconciling the Three Sustainability Dimensions

Ever since the international work on sustainable development sparked off with the Brundtland report in the late 1980s, its main concerns have increasingly centered around global issues pertaining to the three interconnected “pillars” of sustainable development—environmental, social and economic—whose interdependent nature has emerged with growing clarity (Elliot 2013). In order to illustrate their mutual interdependence, Raworth (2012) puts forth a circular model for sustainable development that incorporates social and economic development within the ← xviii | xix → overarching nine planetary boundaries. The model identifies “an environmentally safe and socially just space for humanity” (p. 4) where “inclusive and sustainable economic development” (p. 4) takes place in between the inner boundary, which signifies the social dimension which holds various forms of human scarcities, and the outer boundary or “ceiling,” which builds on the nine planetary boundaries that cannot be crossed without serious implications for the natural systems of the planet upon which humanity depends.

Fig I.1: The safe and just space for humanity (Raworth 2012).

In this way, the concept of sustainable development has evolved to entail a “creative tension between some core principles and an openness to reinterpretation and adaptation to different social, economic and ecological contexts” (Kates, Parris and Leiserowitz 2005: 20). This book relies on this “creative tension” and acknowledges sustainability as an important concept and idea to be used in diverse ← xix | xx → contexts (Kates, Parris and Leiserowitz 2005). It attempts to make constructive use of the concept’s ambiguous character for the sake of opening up to—perhaps unforeseen—sustainability-relevant interests and ideas. In our view, and as suggested by Elliot (2013: 19), the attractiveness of the concept of sustainable development lies exactly “in the varied ways in which it can be interpreted, enabling diverse and possibly incompatible interests to ‘sign up to’ sustainable development”.

Considering the apparent interdependence and the need for reconciliation between the three sustainability dimensions, the book attempts to take a first step towards such an integral approach in journalism studies with its analytical focus on sustainable journalism, which we propose as a possible path for meeting the journalism crisis outlined next.

The Journalism Crisis

The first thing that comes to mind when thinking about journalism is probably the professional journalist embracing a professional identity based on a professional culture and ideology, matched with a more or less uniform and habitual set of journalistic practices (Deuze 2005; Zelizer 1993), working in traditional media houses in traditional media such as radio, newspapers and television. This picture of journalism stems from the modern project with journalism as the conveyor of democratically significant information, nationally oriented, adhering to journalistic norms such as objectivity, truthfulness and accuracy, functioning as the watchdog/third or fourth estate (cf. Brüggemann in this volume). Obviously, traditional journalism of this kind still has an important role in the democratic society and a profound impact.

However, it is also true that journalism has undergone profound change and experienced a great deal of turmoil over the last two decades both as a business and a profession (Wahl-Jorgensen et al. 2016). As has been demonstrated by media business research (Krumsvik and Ots 2016), this commotion is not least due to the proliferation of digital media including alternative news outlets such as, in a Western context, BuzzFeed and Huffington Post; news aggregators such as Google News; blogs; and SNSs like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Digital media are easily accessible from various mobile devices (tablets, smartphones) and, in order to meet the fierce competition among the vast array of information brokers, traditional journalism has more or less been forced to go digital in electronic newspapers, web-TV, and so forth (Usher 2010; Hermida 2010; Peters and Broersma 2013; Picard 2016). Traditional journalists have become increasingly dependent on SNSs as sources since they often discover news events on social media where citizens are able to, in real time, report on incidents around the world by means of, for instance, videos uploaded to YouTube, status updates on Facebook or tweets on Twitter. The digitization of media and journalism has resulted in the partial ← xx | xxi → dissolution of previously evident boundaries and distinctions, blurring the line between professional journalists and other types of information brokers (Edström, Kenyon and Svensson 2016; Carlson and Lewis 2015; Deuze 2007; Stiernstedt in this volume).

Digital media have rendered an interactive dimension to the journalistic practice, and the term “prod-users” has been suggested to highlight the interactive possibilities of the digital media landscape, where the former “audience” has transformed into both producers and users simultaneously (Bruns 2009). The public is able to pick from a wider choice of traditional and digital sources, and this has created possibilities for people to function as their own gatekeepers in the selection of information. The culture of sharing, which is fostered within online networks (Cardoso 2012), has resulted in transformed patterns of news consumption where people are able to recommend (news) links to friends or followers on Facebook or Twitter, who in turn might pick and choose from a virtually infinite amount of shared information. Admittedly, this information does not always meet the journalistic standards of “truthfulness” and “accuracy” but it has transformed the ways in which information is disseminated, gathered and perceived, which strongly affects the journalistic practice, putting traditional journalism under severe pressure.

From an economic perspective, the business of journalism is changing (Arrese 2016). The rapid increase in supply of information and entertainment to citizens makes traditional journalistic media compete with a vast number of media for both advertising revenue as well as consumer spending. What was initially seen as a crisis of the printed press has now turned into a crisis for journalism as a business model. It does not appear economically sustainable in its current form (McChesney 2016; Pickard in this volume). The question is how future, viable business models for journalism evolve as the old models crumble.

The question of how to renew the business of journalism has gained increasing interest, but with a strong research emphasis on merely how to transfer the existing business model into a digital world, rather than how to actually transform or renew the business itself (Goyanes 2014; Kammer et al. 2015). That is, much effort has been focused on how newspapers can erect paywalls that force consumers to pay for news online just like they pay for a printed newspaper (e.g. Arrese 2016). This perspective is basically a response to the crisis of the printed press. If, however, the crisis is for the business of news/journalism, then digitization will not help the news organizations. In the latter case, there is need for a more fundamental re-evaluation of how companies make business out of journalism, and also how new journalistic practices, such as citizen journalism, social media and prod-usage, are included in future business models.

The concept of sustainable journalism, which will be further developed in the next section, involves journalism in a broad sense: traditional journalism in ← xxi | xxii → traditional media, traditional journalism in digital media, emerging forms of journalism such as citizen journalism, traditional media companies and freelance journalism, and, not least, the relationships between traditional forms and emerging forms of journalism as a practice and business.

Sustainable Journalism

Details

- Pages

- XXXIV, 374

- Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433143809

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433143816

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433143823

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433134418

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433134401

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11462

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (September)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2017. XXXIV, 374 pp.